Going out for a Bike Ride

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Hazard of Dunedin's Urban Streams

Flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams Review of Dunedin City District Plan: Natural Hazards Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-478-37680-7 Published June 2014 Prepared by: Michael Goldsmith, Manager Natural Hazards Jacob Williams, Natural Hazards Analyst Jean-Luc Payan, Investigations Engineer Hank Stocker (GeoSolve Ltd) Cover image: Lower reaches of the Water of Leith, May 1923 Flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams i Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Describing the flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams .................................................. 4 2.1 Characteristics of flood events ............................................................................... 4 2.2 Floodplain mapping ............................................................................................... 4 2.3 Other hazards ...................................................................................................... -

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 - Agenda

Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 - Agenda Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 Meeting will be held in the Council Chamber, Level 2, Philip Laing House 144 Rattray Street, Dunedin Members: Cr Andrew Noone, Chairperson Cr Carmen Hope Cr Michael Laws, Deputy Chairperson Cr Gary Kelliher Cr Hilary Calvert Cr Kevin Malcolm Cr Michael Deaker Cr Gretchen Robertson Cr Alexa Forbes Cr Bryan Scott Hon Cr Marian Hobbs Cr Kate Wilson Senior Officer: Sarah Gardner, Chief Executive Meeting Support: Liz Spector, Committee Secretary 25 November 2020 01:00 PM Agenda Topic Page 1. APOLOGIES Cr Deaker and Cr Hobbs have submitted apologies. 2. CONFIRMATION OF AGENDA Note: Any additions must be approved by resolution with an explanation as to why they cannot be delayed until a future meeting. 3. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Members are reminded of the need to stand aside from decision-making when a conflict arises between their role as an elected representative and any private or other external interest they might have. 4. PUBLIC FORUM Members of the public may request to speak to the Council. 4.1 Mr Bryce McKenzie has requested to speak to the Council about the proposed Freshwater Regulations. 5. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 4 The Council will consider minutes of previous Council Meetings as a true and accurate record, with or without changes. 5.1 Minutes of the 28 October 2020 Council Meeting 4 6. ACTIONS (Status of Council Resolutions) 12 The Council will review outstanding resolutions. 7. MATTERS FOR COUNCIL CONSIDERATION 14 1 Council Meeting Agenda - 25 November 2020 - Agenda 7.1 CURRENT RESPONSIBILITIES IN RELATION TO DRINKING WATER 14 This paper is provided to inform the Council on Otago Regional Council’s (ORC) current responsibilities in relation to drinking water. -

Kewanee's Love Affair with the Bicycle

February 2020 Kewanee’s Love Affair with the Bicycle Our Hometown Embraced the Two-Wheel Mania Which Swept the Country in the 1880s In 1418, an Italian en- Across Europe, improvements were made. Be- gineer, Giovanni Fontana, ginning in the 1860s, advances included adding designed arguably the first pedals attached to the front wheel. These became the human-powered device, first human powered vehicles to be called “bicycles.” with four wheels and a (Some called them “boneshakers” for their rough loop of rope connected by ride!) gears. To add stability, others experimented with an Fast-forward to 1817, oversized front wheel. Called “penny-farthings,” when a German aristo- these vehicles became all the rage during the 1870s crat and inventor, Karl and early 1880s. As a result, the first bicycle clubs von Drais, created a and competitive races came into being. Adding to two-wheeled vehicle the popularity, in 1884, an Englishman named known by many Thomas Stevens garnered notoriety by riding a names, including Drais- bike on a trip around the globe. ienne, dandy horse, and Fontana’s design But the penny-farthing’s four-foot high hobby horse. saddle made it hazardous to ride and thus was Riders propelled Drais’ wooden, not practical for most riders. A sudden 50-pound frame by pushing stop could cause the vehicle’s mo- off the ground with their mentum to send it and the rider feet. It didn’t include a over the front wheel with the chain, brakes or pedals. But rider landing on his head, because of his invention, an event from which the Drais became widely ack- Believed to term “taking a header” nowledged as the father of the be Drais on originated. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Published by Authority

No. 59 1789 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Published by Authority WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 23 APRIL 1987 CORRIGENDUM Dated at Wellington this 15th day of April 1987. Setting Apart Maori Freehold Land as a Maori Reservation K. T. WETERE, Minister of Maori Affairs. (H.O. M.A. 107/1) 8CL IN the notice issued on the 12th day of November 1986 and pub lished in the New Zealand Gazette, 27 November 1986, No. 189, page 5084, amend the description of the land in the Schedule from Appointment of Queen's Counsel "Part Ngatihaupoto 2D2 as shown on M.L. 660 and being part of the land contained in a partition order of the Maori Land Court dated 18 October 1917 and being all the land in certificate of title, HIS Excellency the Governor-General, acting on the recommendation Volume 132, folio 185 (Taranaki Registry)" to read "Part Ngati of the Attorney-General, and with the concurrence of the Chief haupoto 2D2 as shown on M.L. 660 and being part of the land Justice has been pleased to appoint: contained in a partition order of the Maori Land Court dated 18 October 1917 and being part of the land in certificate of title, Volume Alan Lough Hassan, 132, folio 185 (Taranaki Registry)". Gerald Stewart Tuohy, Peter Aldridge Williams, Dated at Wellington this 18th day of March 1987. David Arthur Rhodes Williams, B. S. ROBINSON, Alan Raymond Galbraith, and Deputy Secretary for Maori Affairs. John Joseph McGrath. (M.A. H.O. 21/3/7; D.O. 2/439) to be Queen's Counsel. -

Surface Water Quality the Water of Leith and Lindsay's Creek Kaikorai

Surface water quality The Water of Leith and Lindsay’s Creek Kaikorai Stream Waitati River and Carey’s Creek © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN 1-877265-67-5 Published August 2008 Water of Leith, Kaikorai, Waitati and Carey’s Creek i Foreword To help protect water quality, the Otago Regional Council (ORC) carries out long- term water quality monitoring as part of a State of the Environment programme. To supplement this information, targeted and detailed short-term monitoring programmes are also implemented in some catchments. This report provides the results from more detailed investigations carried out in three catchments: Water of Leith Kaikorai Stream Waitati River and Carey’s Creek The Water of Leith and Kaikorai Stream are both located in Dunedin and drain typical residential and industrial areas. Both watercourses have many stormwater outfalls which compromise water quality. The Waitati River and Carey’s Creek have little development in their catchments. The upper catchments are forested while lower in the catchment, pasture dominates. Water quality is generally very good. This report forms a baseline study from which ORC and local community programmes can work together to address various issues in the catchments. It is hoped that these catchment programmes will promote environmentally sound practices which will sustain and improve water quality. Water of Leith, Kaikorai, Waitati and Careys Creek Water of Leith, Kaikorai, Waitati and Carey’s Creek ii Water of Leith, Kaikorai, Waitati and Careys Creek Water of Leith, Kaikorai, Waitati and Carey’s Creek iii Executive summary Between July 2007 and March 2008, the Otago Regional Council (ORC) carried out intensive water quality monitoring programmes in the following catchments: Water of Leith Kaikorai Stream Waitati River and Carey’s Creek The aim of this monitoring was to establish a baseline water quality. -

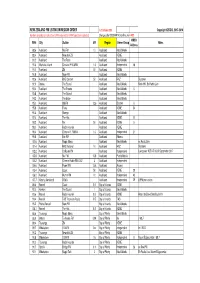

NZL FM List in Regional Order Oct19.Xlsx

NEW ZEALAND FM LISTING IN REGION ORDER to 1 October 2019 Copyright NZRDXL 2017-2019 Full-time broadcasters plus their LPFM relays (other LPFM operators excluded) Changes after 2020 WRTH Deadline are in RED WRTH MHz City Station kW Region Owner/Group Notes Address 88.6 Auckland Mai FM 10 Auckland MediaWorks 89.4 Auckland Newstalk ZB Auckland NZME 90.2 Auckland The Rock Auckland MediaWorks 90.6 Waiheke Island Chinese R 90.6FM 1.6 Auckland Independent 18 91.0 Auckland ZM 50 Auckland NZME 91.8 Auckland More FM Auckland MediaWorks 92.6 Auckland RNZ Concert 50 Auckland RNZ Skytower 92.9 Orewa The Sound Auckland MediaWorks Moirs Hill. Ex Radio Live 93.4 Auckland The Breeze Auckland MediaWorks 5 93.8 Auckland The Sound Auckland MediaWorks 94.2 Auckland The Edge Auckland MediaWorks 95.0 Auckland 95bFM 12.6 Auckland Student 6 95.8 Auckland Flava Auckland NZME 34 96.6 Auckland George Auckland MediaWorks 97.4 Auckland The Hits Auckland NZME 10 98.2 Auckland Mix 50 Auckland NZME 5 99.0 Auckland Radio Hauraki Auckland NZME 99.4 Auckland Chinese R. FM99.4 1.6 Auckland Independent 21 99.8 Auckland Life FM Auckland Rhema 100.6 Auckland Magic Music Auckland MediaWorks ex Radio Live 101.4 Auckland RNZ National 10 Auckland RNZ Skytower 102.2 Auckland OnRoute FM Auckland Independent Low power NZTA Trial till September 2017 103.8 Auckland Niu FM 15.8 Auckland Pacific Media 104.2 Auckland Chinese Radio FM104.2 3 Auckland Independent 104.6 Auckland Planet FM 15.8 Auckland Access 105.4 Auckland Coast 50 Auckland NZME 29 106.2 Auckland Humm FM 10 Auckland Independent -

55TH ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING of the IADR ANZ DIVISION DUNEDIN PUBLIC ART GALLERY the OCTAGON, DUNEDIN, NZ 23-26 AUGUST, 2015 ! Table!Of!Contents!

! ! ! ! 55TH ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING OF THE IADR ANZ DIVISION DUNEDIN PUBLIC ART GALLERY THE OCTAGON, DUNEDIN, NZ 23-26 AUGUST, 2015 ! Table!of!contents! Welcome!to!IADR!ANZ!2015! 3! Quick!start!guide! 6! Information!for!registrants! 7! Dunedin!city!maps! 8M9! Information!for!presenters! 10! Local!Organising!Committee! 11! Colgate!Eminent!Lecturer!! 12! Keynote!presenters! 13! IADR!ANZ!2015!programme!atMaMglance! 17M18! Oral!presentation!sessions! ! Monday!24!August! 19! Tuesday!25!August! 20! Wednesday!26!August! 22! Poster!sessions! ! Monday!24!August!M!Colgate!Poster!Competition!session! 24! Tuesday!25!August!M!General!poster!session! 28! Research!abstracts!(listed!by!presenting!author)! ! Abstracts!from!oral!presentations! 30! Abstracts!from!poster!presentations! 63! Presenter!index! 114! List!of!delegates! 120! IADR!ANZ!2015!PROGRAMME!AND!ABSTRACTS! PAGE!!2! ! Welcome!to!IADR!ANZ!2015! Konstantinos! Michalakis! (Aristotle! University! of! Thessaloniki! School! of! ! Dentistry! and! Tufts! University! School! of! Dental! Medicine),! and! Professor! Svante! TWetman! (University! of! Copenhagen).! The!format!of!the!scientific!programme!is!modelled! on!last!year’s!Brisbane!meeting!Which!proved!to!be! extremely!successful,!and!I!look!forWard!to!seeing!it! folloWed! at! future! meetings.! ! 135! abstracts! Were! submitted!of!Which!133!Were!accepted!for!inclusion! ! in! the! scientific! programme,! With! 183! registered! Tēnā! koutou,! haere! mai!Aotearoa;! Greetings! and! delegates! attending! the! meeting.! This! is! an! welcome!to!New!Zealand.! -

Fauna of New Zealand, Website Copy

Vink, C. J. 2002: Lycosidae (Arachnida: Araneae). Fauna of New Zealand 44, 94 pp. INVERTEBRATE SYSTEMATICS ADVISORY GROUP REPRESENTATIVES OF L ANDCARE RESEARCH Dr O. R. W. Sutherland Landcare Research Lincoln Agriculture & Science Centre P.O. Box 69, Lincoln, New Zealand Dr T.K. Crosby and Dr M.-C. Larivière Landcare Research Mount Albert Research Centre Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF U NIVERSITIES Dr R.M. Emberson Ecology and Entomology Group Soil, Plant, and Ecological Sciences Division P.O. Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF MUSEUMS Mr R.L. Palma Natural Environment Department Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF O VERSEAS I NSTITUTIONS Dr M. J. Fletcher Director of the Collections NSW Agricultural Scientific Collections Unit Forest Road, Orange NSW 2800, Australia * * * SERIES EDITOR Dr T. K. Crosby Landcare Research Mount Albert Research Centre Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 44 Lycosidae (Arachnida: Araneae) C. J. Vink Ecology and Entomology Group P O Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand [email protected] Manaak i W h e n u a P R E S S Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2002 4 Vink (2002): Lycosidae (Arachnida: Araneae) Copyright © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2002 No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping information retrieval systems, or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. -

Otago Peninsula Plants

Otago Peninsula Plants An annotated list of vascular plants growing in wild places Peter Johnson 2004 Published by Save The Otago Peninsula (STOP) Inc. P.O. Box 23 Portobello Dunedin, New Zealand ISBN 0-476-00473-X Contents Introduction...........................................................................................3 Maps......................................................................................................4 Study area and methods ........................................................................6 Plant identification................................................................................6 The Otago Peninsula environment........................................................7 Vegetation and habitats.........................................................................8 Analysis of the flora............................................................................10 Plant species not recently recorded.....................................................12 Abundance and rarity of the current flora...........................................13 Nationally threatened and uncommon plants......................................15 Weeds..................................................................................................17 List of plants .......................................................................................20 Ferns and fern allies ........................................................................21 Gymnosperms ..................................................................................27 -

THE ZEN of CRUISING NEW ZEALAND Text and Photos by Amanda Castleman

>travelgirl glimpse: new zealand Hei Matau: Safe Passage Across Water THE ZEN OF CRUISING NEW ZEALAND text and photos by Amanda Castleman An albatross lazes along beside the boat. Our engines push against the wind and on-rushing tide off New Zealand’s Otago Peninsula. But this bird just cruises — look ma, no hands! — on its 10-foot wingspan. That same power carries non-breeding toroa (royal northern albatrosses) on circumpolar flights, skating along the Antarctic fringes and nesting on far-flung, salt-chapped islands. Just one colony, here at Taiaroa Head, deigns to live on a human-inhabited mainland. Otago is an exception-worthy place with its free- hold farms, sun-soaked coves and volcanic sea cliffs. Sand dunes rear up 325 feet in one area. The nation’s only castle rides the peninsula’s spine: a monument to William Larnach, a gold miner turned banker and 19th-century politician. Nearby lives the world’s rarest penguin, the native Hoiho (“noise shouter” in Maori), Mount Cargill’s trails overlook Dunedin and the Otago peninsula, home to the only colony of royal northern albatrosses on a human-inhabited mainland. which slouches on the $5 bill beside some giant daisies. 54 kiXm\c^`ic nnn%kiXm\c^`ic`eZ%Zfd 55 >travelgirl glimpse: new zealand Like much of New Zealand, Otago’s natural beauty is epic. Wide-screen. Almost over-bright, as if Hobbit Director Peter Jackson filmed the whole Colorado-sized country in 48 frames per second. And though I’ve been warned — begged even — not to mention “bloody Middle Earth again,” I can’t help myself.