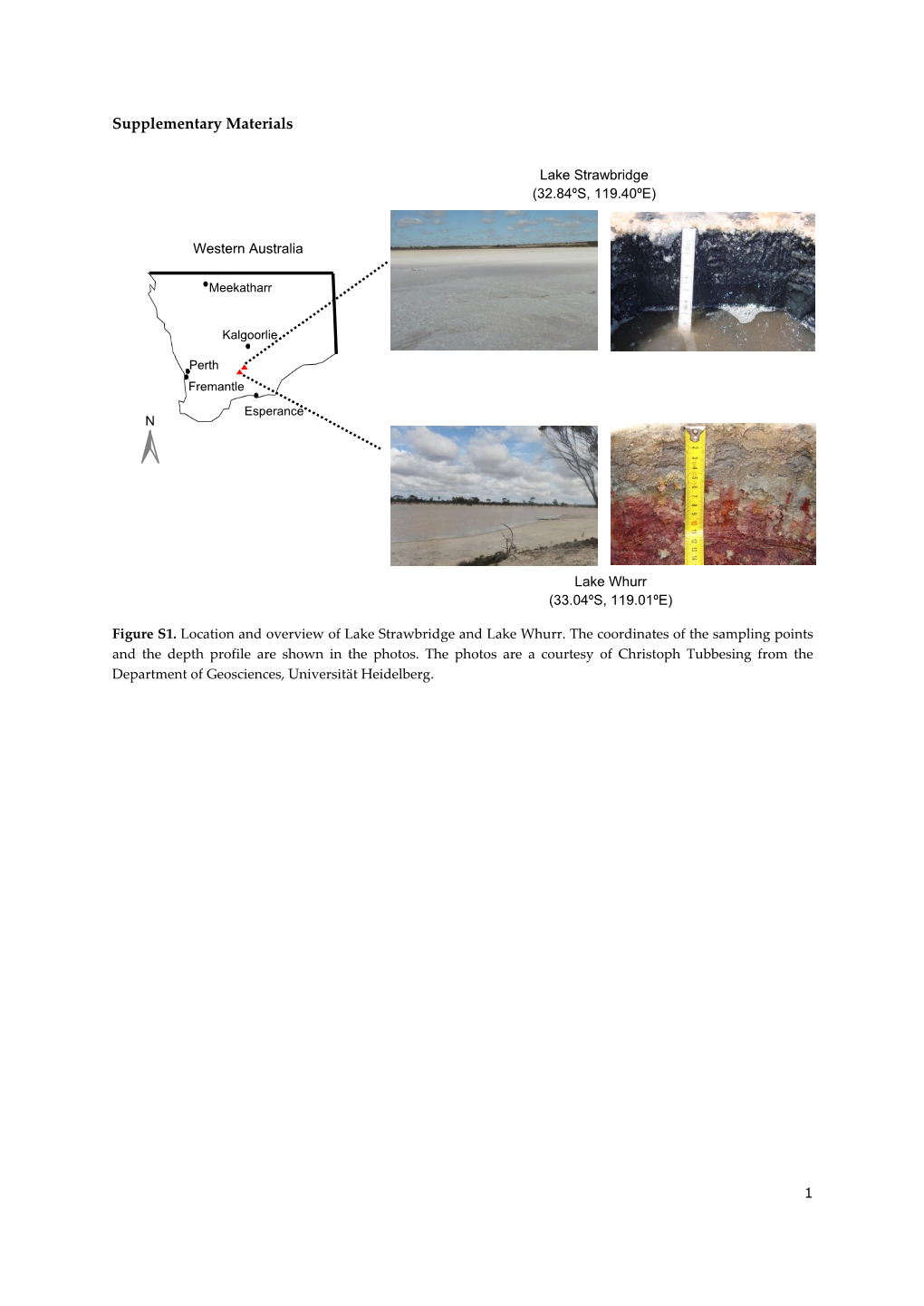

Supplementary Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Quality Draft Genome Sequences of Five Anaerobic Oral Bacteria and Description of Peptoanaerobacter Stomatis Gen

Sizova et al. Standards in Genomic Sciences (2015) 10:37 DOI 10.1186/s40793-015-0027-8 EXTENDED GENOME REPORT Open Access High-quality draft genome sequences of five anaerobic oral bacteria and description of Peptoanaerobacter stomatis gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Peptostreptococcaceae Maria V. Sizova1, Amanda Chilaka1, Ashlee M. Earl2, Sebastian N. Doerfert1, Paul A. Muller1, Manolito Torralba3, Jamison M. McCorrison3, A. Scott Durkin3, Karen E. Nelson3 and Slava S. Epstein1* Abstract Here we report a summary classification and the features of five anaerobic oral bacteria from the family Peptostreptococcaceae. Bacterial strains were isolated from human subgingival plaque. Strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 represent the first known cultivable members of “yet uncultured” human oral taxon 081; strain AS15 belongs to “cultivable” human oral taxon 377. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons, strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 are distantly related to Eubacterium yurii subs. yurii and Filifactor alocis, with 93.2 – 94.4 % and 85.5 % of sequence identity, respectively. The genomes of strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, OBRC8 and AS15 are 2,541,543; 2,312,592; 2,594,242; 2,553,276; and 2,654,638 bp long. The genomes are comprised of 2277, 1973, 2325, 2277, and 2308 protein-coding genes and 54, 57, 54, 36, and 28 RNA genes, respectively. Based on the distinct characteristics presented here, we suggest that strains ACC19a, CM2, CM5, and OBRC8 represent a novel genus and species within the family Peptostreptococcaceae, for which we propose the name Peptoanaerobacter stomatis gen. nov., sp. nov. The type strain is strain ACC19aT (=HM-483T; =DSM 28705T;=ATCC BAA-2665T). -

Sporulation Evolution and Specialization in Bacillus

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473793; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Research article From root to tips: sporulation evolution and specialization in Bacillus subtilis and the intestinal pathogen Clostridioides difficile Paula Ramos-Silva1*, Mónica Serrano2, Adriano O. Henriques2 1Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Oeiras, Portugal 2Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Oeiras, Portugal *Corresponding author: Present address: Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Marine Biodiversity, Leiden, The Netherlands Phone: 0031 717519283 Email: [email protected] (Paula Ramos-Silva) Running title: Sporulation from root to tips Keywords: sporulation, bacterial genome evolution, horizontal gene transfer, taxon- specific genes, Bacillus subtilis, Clostridioides difficile 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473793; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Abstract Bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum are able to enter a developmental pathway that culminates with the formation of a highly resistant, dormant spore. Spores allow environmental persistence, dissemination and for pathogens, are infection vehicles. In both the model Bacillus subtilis, an aerobic species, and in the intestinal pathogen Clostridioides difficile, an obligate anaerobe, sporulation mobilizes hundreds of genes. -

Heat Resistant Thermophilic Endospores in Cold Estuarine Sediments

Heat resistant thermophilic endospores in cold estuarine sediments Emma Bell Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Engineering February 2016 Abstract Microbial biogeography explores the spatial and temporal distribution of microorganisms at multiple scales and is influenced by environmental selection and passive dispersal. Understanding the relative contribution of these factors can be challenging as their effects can be difficult to differentiate. Dormant thermophilic endospores in cold sediments offer a natural model for studies focusing on passive dispersal. Understanding distributions of these endospores is not confounded by the influence of environmental selection; rather their occurrence is due exclusively to passive transport. Sediment heating experiments were designed to investigate the dispersal histories of various thermophilic spore-forming Firmicutes in the River Tyne, a tidal estuary in North East England linking inland tributaries with the North Sea. Microcosm incubations at 50-80°C were monitored for sulfate reduction and enriched bacterial populations were characterised using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, functional gene clone libraries and high-throughput sequencing. The distribution of thermophilic endospores among different locations along the estuary was spatially variable, indicating that dispersal vectors originating in both warm terrestrial and marine habitats contribute to microbial diversity in estuarine and marine environments. In addition to their persistence in cold sediments, some endospores displayed a remarkable heat-resistance surviving multiple rounds of autoclaving. These extremely heat-resistant endospores are genetically similar to those detected in deep subsurface environments, including geothermal groundwater investigated from a nearby terrestrial borehole drilled to >1800 m depth with bottom temperatures in excess of 70°C. -

WO 2018/064165 A2 (.Pdf)

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/064165 A2 05 April 2018 (05.04.2018) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: A61K 35/74 (20 15.0 1) C12N 1/21 (2006 .01) — without international search report and to be republished (21) International Application Number: upon receipt of that report (Rule 48.2(g)) PCT/US2017/053717 — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) (22) International Filing Date: 27 September 2017 (27.09.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Langi English (30) Priority Data: 62/400,372 27 September 2016 (27.09.2016) US 62/508,885 19 May 2017 (19.05.2017) US 62/557,566 12 September 2017 (12.09.2017) US (71) Applicant: BOARD OF REGENTS, THE UNIVERSI¬ TY OF TEXAS SYSTEM [US/US]; 210 West 7th St., Austin, TX 78701 (US). (72) Inventors: WARGO, Jennifer; 1814 Bissonnet St., Hous ton, TX 77005 (US). GOPALAKRISHNAN, Vanch- eswaran; 7900 Cambridge, Apt. 10-lb, Houston, TX 77054 (US). (74) Agent: BYRD, Marshall, P.; Parker Highlander PLLC, 1120 S. Capital Of Texas Highway, Bldg. One, Suite 200, Austin, TX 78746 (US). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Compile.Xlsx

Silva OTU GS1A % PS1B % Taxonomy_Silva_132 otu0001 0 0 2 0.05 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria_un;Acidobacteria_un;Acidobacteria_un;Acidobacteria_un; otu0002 0 0 1 0.02 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteriia;Solibacterales;Solibacteraceae_(Subgroup_3);PAUC26f; otu0003 49 0.82 5 0.12 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Aminicenantia;Aminicenantales;Aminicenantales_fa;Aminicenantales_ge; otu0004 1 0.02 7 0.17 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;AT-s3-28;AT-s3-28_or;AT-s3-28_fa;AT-s3-28_ge; otu0005 1 0.02 0 0 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Blastocatellia_(Subgroup_4);Blastocatellales;Blastocatellaceae;Blastocatella; otu0006 0 0 2 0.05 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;Subgroup_7;Subgroup_7_fa;Subgroup_7_ge; otu0007 1 0.02 0 0 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;ODP1230B23.02;ODP1230B23.02_or;ODP1230B23.02_fa;ODP1230B23.02_ge; otu0008 1 0.02 15 0.36 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_17;Subgroup_17_or;Subgroup_17_fa;Subgroup_17_ge; otu0009 9 0.15 41 0.99 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_21;Subgroup_21_or;Subgroup_21_fa;Subgroup_21_ge; otu0010 5 0.08 50 1.21 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_22;Subgroup_22_or;Subgroup_22_fa;Subgroup_22_ge; otu0011 2 0.03 11 0.27 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_26;Subgroup_26_or;Subgroup_26_fa;Subgroup_26_ge; otu0012 0 0 1 0.02 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_5;Subgroup_5_or;Subgroup_5_fa;Subgroup_5_ge; otu0013 1 0.02 13 0.32 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_6;Subgroup_6_or;Subgroup_6_fa;Subgroup_6_ge; otu0014 0 0 1 0.02 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_6;Subgroup_6_un;Subgroup_6_un;Subgroup_6_un; otu0015 8 0.13 30 0.73 Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Subgroup_9;Subgroup_9_or;Subgroup_9_fa;Subgroup_9_ge; -

C. Difficile: Trials, Treatments and New Guidelines

C. difficile: trials, treatments and new guidelines CONTENTS REVIEW: Vulnerability of long-term care facility residents to Clostridium difficile infection due to microbiome disruptions FUTURE MICROBIOLOGY Vol. 13, No. 13 INTERVIEW: The gut microbiome and the potentials of probiotics: an interview with Simon Gaisford FUTURE MICROBIOLOGY Vol. 14, No. 4 REVIEW: Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection: current and alternative therapeutic strategies FUTURE MICROBIOLOGY Vol. 13, No. 4 EDITORIAL: Microbiome therapeutics – the pipeline for C. difficile infection INTERVIEW: Updates on C. difficile: from clinical trials and guidelines – an interview with Yoav Golan NEWS ARTICLE: Could common painkillers promote C. difficile infection? Review For reprint orders, please contact: [email protected] Vulnerability of long-term care facility residents to Clostridium difficile infection due to microbiome disruptions Beth Burgwyn Fuchs*,1, Nagendran Tharmalingam1 & Eleftherios Mylonakis**,1 1Rhode Island Hospital, Alpert Medical School & Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island 02903 *Author for correspondence: Tel.: +401 444 7309; Fax: +401 606 5624; Helen [email protected]; **Author for correspondence: Tel.: +401 444 7845; Fax: +401 444 8179; [email protected] Aging presents a significant risk factor for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). A disproportionate number of CDIs affect individuals in long-term care facilities compared with the general population, likely due to the vulnerable nature of the residents and shared environment. Review of the literature cites a number of underlying medical conditions such as the use of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, chemotherapy, renal disease and feeding tubes as risk factors. These conditions alter the intestinal environment through direct bacterial killing, changes to pH that influence bacterial stabilities or growth, or influence nutrient availability that direct population profiles. -

The Clostridioides Difficile Species Problem: Global Phylogenomic 2 Analysis Uncovers Three Ancient, Toxigenic, Genomospecies

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.21.307223; this version posted September 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The Clostridioides difficile species problem: global phylogenomic 2 analysis uncovers three ancient, toxigenic, genomospecies 3 Daniel R. Knight1, Korakrit Imwattana2,3, Brian Kullin4, Enzo Guerrero-Araya5,6, Daniel Paredes- 4 Sabja5,6,7, Xavier Didelot8, Kate E. Dingle9, David W. Eyre10, César Rodríguez11, and Thomas V. 5 Riley1,2,12,13* 6 1 Medical, Molecular and Forensic Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia, Australia. 2 School of 7 Biomedical Sciences, the University of Western Australia, Nedlands, Western Australia, Australia. 3 Department of 8 Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. 4 Department of Pathology, University 9 of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. 5 Microbiota-Host Interactions and Clostridia Research Group, Facultad de 10 Ciencias de la Vida, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile. 6 Millenium Nucleus in the Biology of Intestinal 11 Microbiota, Santiago, Chile. 7Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843, USA. 8 School 12 of Life Sciences and Department of Statistics, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK. 9 Nuffield Department of Clinical 13 Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical 14 Research Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK. 10 Big Data Institute, Nuffield Department of Population Health, 15 University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, 16 John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK. -

Identity, Abundance, and Reactivation Kinetics of Thermophilic Fermentative Endospores in Cold Marine Sediment and Seawater

fmicb-08-00131 February 2, 2017 Time: 16:19 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 06 February 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00131 Identity, Abundance, and Reactivation Kinetics of Thermophilic Fermentative Endospores in Cold Marine Sediment and Seawater Marta Volpi*, Bente Aa. Lomstein, Andreas Sichert†, Hans Røy, Bo B. Jørgensen and Kasper U. Kjeldsen* Center for Geomicrobiology, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Edited by: Baolei Jia, Cold marine sediments harbor endospores of fermentative and sulfate-reducing, Chung-Ang University, South Korea thermophilic bacteria. These dormant populations of endospores are believed to Reviewed by: accumulate in the seabed via passive dispersal by ocean currents followed by Juan M. Gonzalez, Spanish National Research Council, sedimentation from the water column. However, the magnitude of this process is poorly Spain understood because the endospores present in seawater were so far not identified, Jeremy Dodsworth, California State University, and only the abundance of thermophilic sulfate-reducing endospores in the seabed San Bernardino, USA has been quantified. We investigated the distribution of thermophilic fermentative Lars Wörmer, endospores (TFEs) in water column and sediment of Aarhus Bay, Denmark, to test the University of Bremen, Germany role of suspended dispersal and determine the rate of endospore deposition and the *Correspondence: Marta Volpi endospore abundance in the sediment. We furthermore aimed to determine the time [email protected] course of reactivation of the germinating TFEs. TFEs were induced to germinate and Kasper U. Kjeldsen ◦ [email protected] grow by incubating pasteurized sediment and water samples anaerobically at 50 C. We †Present address: observed a sudden release of the endospore component dipicolinic acid immediately Andreas Sichert, upon incubation suggesting fast endospore reactivation in response to heating. -

A Pyrosequencing Investigation of Differences in the Feline Subgingival Microbiota in Health, Gingivitis and Mild Periodontitis

RESEARCH ARTICLE A Pyrosequencing Investigation of Differences in the Feline Subgingival Microbiota in Health, Gingivitis and Mild Periodontitis Stephen Harris1, Julie Croft1, Ciaran O’Flynn1, Oliver Deusch1, Alison Colyer1, Judi Allsopp1, Lisa Milella2, Ian J. Davis1* 1 The WALTHAM Centre for Pet Nutrition, Mars Petcare UK, Leicestershire, United Kingdom, 2 The Veterinary Dental Surgery, Surrey, United Kingdom * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Periodontitis is the most frequently diagnosed health problem in cats yet little is known ’ Citation: Harris S, Croft J, O Flynn C, Deusch O, about the bacterial species important for the disease. The objective of this study was to Colyer A, Allsopp J, et al. (2015) A Pyrosequencing < Investigation of Differences in the Feline Subgingival identify bacterial species associated with health, gingivitis or mild periodontitis ( 25% Microbiota in Health, Gingivitis and Mild Periodontitis. attachment loss) in feline plaque. Knowledge of these species is a first step in understand- PLoS ONE 10(11): e0136986. doi:10.1371/journal. ing the potential for improving oral health of cats via dietary interventions that alter the pro- pone.0136986 portions of influential species. Subgingival plaque samples were collected from 92 cats with Editor: A Al-Ahmad, University Hospital of the Albert- healthy gingiva, gingivitis or mild periodontitis. Pyrosequencing of the V1-V3 region of the Ludwigs-University Freiburg, GERMANY 16S rDNA from these plaque samples generated more than one million reads and identified Received: May 29, 2015 a total of 267 operational taxonomic units after bioinformatic and statistical analysis. Por- Accepted: August 11, 2015 phyromonas was the most abundant genus in all gingival health categories, particularly in Moraxella Published: November 25, 2015 health along with and Fusobacteria. -

The Severity of Human Peri-Implantitis Lesions Correlates with the Level Of

University of Birmingham The severity of human peri-implantitis lesions correlates with the level of submucosal microbial dysbiosis Kroeger, Annika; Hülsmann, Claudia; Fickl, Stefan; Spinell, Thomas; Huttig, Fabian; Kaufmann, Frederic; Heimbach, Andre; Hoffmann, Per; Enkling, Norbert; Renvert, Stefan ; Schwarz, Frank; Demmer, Ryan T; Papapanou, Panos N; Jepsen, Soren; Kebschull, Moritz DOI: 10.1111/jcpe.13023 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Kroeger, A, Hülsmann, C, Fickl, S, Spinell, T, Huttig, F, Kaufmann, F, Heimbach, A, Hoffmann, P, Enkling, N, Renvert, S, Schwarz, F, Demmer, RT, Papapanou, PN, Jepsen, S & Kebschull, M 2018, 'The severity of human peri-implantitis lesions correlates with the level of submucosal microbial dysbiosis', Journal of Clinical Periodontology, vol. 45, no. 12, pp. 1498-1509. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13023 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility 3/12/2018 "This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Kroger et al, Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 2018, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13023. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Use of Self-Archived Versions." General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. -

Dysbiosis and Ecotypes of the Salivary Microbiome Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Assistance in Diagnosis of Diseases Using Oral Bacterial Profiles

fmicb-09-01136 May 28, 2018 Time: 15:53 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 30 May 2018 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01136 Dysbiosis and Ecotypes of the Salivary Microbiome Associated With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Assistance in Diagnosis of Diseases Using Oral Bacterial Profiles Zhe Xun1, Qian Zhang2,3, Tao Xu1*, Ning Chen4* and Feng Chen2,3* 1 Department of Preventive Dentistry, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, Beijing, China, 2 Central Laboratory, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, Beijing, China, 3 National Engineering Laboratory for Digital and Material Technology of Stomatology, Beijing Key Laboratory of Digital Stomatology, Beijing, China, 4 Department Edited by: of Gastroenterology, Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, China Steve Lindemann, Purdue University, United States Reviewed by: Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are chronic, idiopathic, relapsing disorders of Christian T. K.-H. Stadtlander unclear etiology affecting millions of people worldwide. Aberrant interactions between Independent Researcher, St. Paul, MN, United States the human microbiota and immune system in genetically susceptible populations Gena D. Tribble, underlie IBD pathogenesis. Despite extensive studies examining the involvement of University of Texas Health Science the gut microbiota in IBD using culture-independent techniques, information is lacking Center at Houston, United States regarding other human microbiome components relevant to IBD. Since accumulated *Correspondence: Feng Chen knowledge has underscored the role of the oral microbiota in various systemic diseases, [email protected] we hypothesized that dissonant oral microbial structure, composition, and function, and Ning Chen [email protected] different community ecotypes are associated with IBD; and we explored potentially Tao Xu available oral indicators for predicting diseases. -

Phylogenomic Analysis of the Family Peptostreptococcaceae (Clostridium Cluster XI) and Proposal for Reclassification of Clostridium Litorale (Fendrich Et Al

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2016), 66, 5506–5513 DOI 10.1099/ijsem.0.001548 Phylogenomic analysis of the family Peptostreptococcaceae (Clostridium cluster XI) and proposal for reclassification of Clostridium litorale (Fendrich et al. 1991) and Eubacterium acidaminophilum (Zindel et al. 1989) as Peptoclostridium litorale gen. nov. comb. nov. and Peptoclostridium acidaminophilum comb. nov. Michael Y. Galperin, Vyacheslav Brover, Igor Tolstoy and Natalya Yutin Correspondence National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Michael Y. Galperin Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20894, USA [email protected] In 1994, analyses of clostridial 16S rRNA gene sequences led to the assignment of 18 species to Clostridium cluster XI, separating them from Clostridium sensu stricto (Clostridium cluster I). Subsequently, most cluster XI species have been assigned to the family Peptostreptococcaceae with some species being reassigned to new genera. However, several misclassified Clostridium species remained, creating a taxonomic conundrum and confusion regarding their status. Here, we have re-examined the phylogeny of cluster XI species by comparing the 16S rRNA gene- based trees with protein- and genome-based trees, where available. The resulting phylogeny of the Peptostreptococcaceae was consistent with the recent proposals on creating seven new genera within this family. This analysis also revealed a tight clustering of Clostridium litorale and Eubacterium acidaminophilum. Based on these data, we propose reassigning these two organisms to the new genus Peptoclostridium as Peptoclostridium litorale gen. nov. comb. nov. (the type species of the genus) and Peptoclostridium acidaminophilum comb. nov., respectively. As correctly noted in the original publications, the genera Acetoanaerobium and Proteocatella also fall within cluster XI, and can be assigned to the Peptostreptococcaceae.