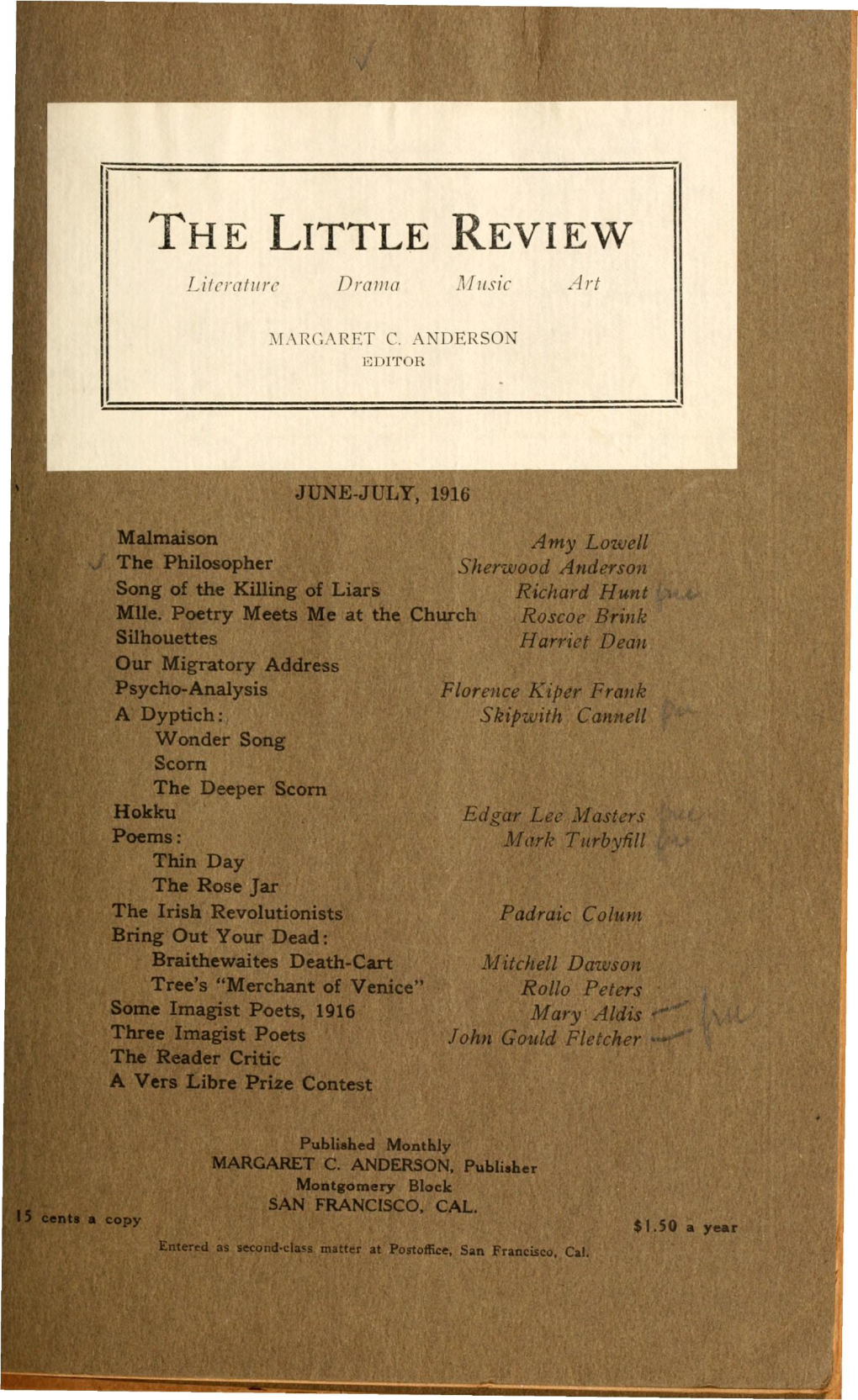

The Little Review. Vol. 3, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bookman Anthology of Verse

The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Edited by John Farrar The Bookman Anthology Of Verse Table of Contents The Bookman Anthology Of Verse..........................................................................................................................1 Edited by John Farrar.....................................................................................................................................1 Hilda Conkling...............................................................................................................................................2 Edwin Markham.............................................................................................................................................3 Milton Raison.................................................................................................................................................4 Sara Teasdale.................................................................................................................................................5 Amy Lowell...................................................................................................................................................7 George O'Neil..............................................................................................................................................10 Jeanette Marks..............................................................................................................................................11 John Dos Passos...........................................................................................................................................12 -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

John Gould Fletcher - Poems

Classic Poetry Series John Gould Fletcher - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive John Gould Fletcher(3 January 1886 – 10 May 1950) John Gould Fletcher was an Imagist poet, author and authority on modern painting. He was born in Little Rock, Arkansas to a socially prominent family. After attending Phillips Academy, Andover Fletcher went on to Harvard University from 1903 to 1907, when he dropped out shortly after his father's death. <b>Background</b> Fletcher lived in England for a large portion of his life. While in Europe he associated with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/amy-lowell/">Amy Lowell</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/ezra-pound/">Ezra Pound</a>, and other Imagist poets, he was one of the six Imagists who adopted the name and stuck to it until their aims were achieved. Fletcher resumed a liaison with Florence Emily “Daisy” Arbuthnot (née Goold) at her house in Kent. She had been married to Malcolm Arbuthnot and Fletcher's adultery with her was the grounds for the divorce. The couple married on July 5, 1916. Their marriage produced no children, but Arbuthnot’s son and daughter from her previous marriage lived with the couple. On January 18, 1936 he married a noted author of children's books, Charlie May Simon. The two of them built "Johnswood", a residence on the bluffs of the Arkansas River outside Little Rock. They traveled frequently, however, to New York for the intellectual stimulation and to the American Southwest for the climate, after Fletcher began to suffer from arthritis. -

An Interpretation of Amy Lowell's Poems from Emerson's

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 13, No. 5, 2017, pp. 38-41 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/9694 www.cscanada.org Picturing Her Landscape: An Interpretation of Amy Lowell’s Poems From Emerson’s Transcendentalism ZHENG Chang[a],* [a]College of International Studies, Southwest University, Chongqing, posthumously won Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926. China. From 1913 until 1925, Lowell was deeply involved in *Corresponding author. Imagism. After the break from Ezra Pound, she redirected Received 18 February 2017; accepted 15 April 2017 the Imagist Movement, and then literary people called Published online 26 May 2017 the American Imagist Movement “Aymgist” Movement, which indicated Amy was really a woman of importance Abstract in this undertaking. The current studies on Imagism have Amy Lowell is a female poet in the American Imagist showed that people have placed much importance on movement in the twentieth century. The former studies Pound, but so rare efforts have been directed to Lowell. have mainly focused on the images in her poems from the Few of her poems have been thoroughly understood, and perspective of aesthetics. Few studies have pointed out much more still waits probing. Considering this problem, the philosophical implications of her poetry. This paper the paper will shed some new light on Lowell studies. A tries to approach Lowell’s poems from the perspective of new spectrum for viewing her poems is from Emerson’s Emerson’s transcendental philosophy. Although the two transcendental philosophy. great figures lived in different times, a direct link between It is hard to find a direct link between imagism and them can hardly be built, they share some similarities, and transcendentalism, for they are the voices of different their poems are colored by transcendental thoughts: Both times in American history. -

Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell's Haunting Modernism

This is a repository copy of Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell's Haunting Modernism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/122951/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Roche, H (2018) Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell's Haunting Modernism. Modernist Cultures, 13 (4). pp. 568-589. ISSN 2041-1022 https://doi.org/10.3366/mod.2018.0230 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Modernist Cultures, published by the Edinburgh University Press, at: http://www.euppublishing.com/loi/mod. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell’s Haunting Modernism Dr Hannah Roche Email: [email protected] Affiliation: University of Leeds 1 Abstract By the end of the twentieth century, Amy Lowell’s poetry had been all but erased from modernism, with her name resurfacing only in relation to her dealings with Ezra Pound, her distant kinship with Robert Lowell, or her correspondence with D. -

The Fragmentation of Imagism It Was 1912, and a New Mode of Poetry Was Taking Root

The Fragmentation of Imagism It was 1912, and a new mode of poetry was taking root. Sparked by the ideas of T.E. Hulme and from distaste of the drippy sentimentalism of the Romantic era (Britannica “Imagist”), Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and H.D. literally wrote the rules of Imagism. Their dry, concise look at an image or “complex,” as Pound described it, helped lay the foundation for modernist poetry. However, the Imagists’ granite rules could not ensure strict adherence to their form, not even from founding members of Imagism themselves. As the years went by, the Imagists themselves grew weary of their own form by both their own admittance and through their later works. Ezra Pound was the first leader of the Imagist movement, and his autocratic grip on the concept of Imagism may be partly to blame for the fragmentation of the movement. Pound makes it quite clear that, “At least for myself, I want [twentieth-century poetry] so, austere, direction, free from emotional slither (“A Retrospect” 23).” He carefully selected and edited poems for published volumes of Imagist poetry, but the appearance of the popular and wealthy poet heiress Amy Lowell swept in a new democratic format for the group’s publications. Authors were to select what they considered their best work, without the stamp of approval from Pound deeming it true to the Imagist credo (Bradshaw 159). Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound clashed quite famously over the direction Imagism would take, as seen in Lowell’s poem to Pound, harshly dubbed “Astigmatism.” The poem pulls no punches; the analogy is clear in Lowell’s image of the Poet smashing lovely flowers of all kinds, saying “They are useless. -

A a a Bath the Day Is Fresh-Washed and Fair, and There Is a Smell Of

Bath The day is fresh-washed and fair, and there is a smell of tulips and narcissus in the air. The sunshine pours in at the bath-room window and bores through the water in the bath- tub in lathes and planes of greenish-white. It cleaves the water into flaws like a jewel, and cracks it to bright light. Little spots of sunshine lie on the surface of the water and dance, dance, and their reflections wobble deliciously over the ceiling; a stir of my finger sets them whirring, reeling. I move a foot and the planes of light in the water jar. I lie back and laugh, and let the green-white wa- ter, the sun-flawed beryl water, flow over me. The day is almost too bright to bear, the green water covers me from the too bright day. I will lie here awhile and play with the water and the sun spots. The sky is blue and high. A crow flaps by the window, and there is a whiff of tulips and narcissus in the air. Amy Lowell1 Reflections I love the invitation this poem seems to offer—to idleness and luxury and pleasant languor. Set in springtime, the poem is relatively untroubled; its only real conflict is that “the day is almost too bright to bear.” What a delicious retreat. Lowell’s poem offers an opportunity to mention something about form: namely, the prose poem, a contradictory sounding name. Here is how one editor, Peter Johnson, explains it in the first issue of The Prose Poem: An International Journal: “Just as black humor straddles the fine line between comedy and tragedy, so the prose poem plants one foot in prose, the other in poetry, both heels resting precariously on banana peels.” In other words, the prose poem looks like prose, but reads like poetry and uses certain traditionally poetic techniques— compression, repetition, fragmentation and, most especially in this case, precise imagery. -

The Queer Modernist Poetics of H.D., Gertrude Stein, and Amy Lowell

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) The Queer Modernist Poetics of H.D., Gertrude Stein, and Amy Lowell Turni Chakrabarti Research Scholar Department of English University of Delhi. Abstract: In recent years, queer theory has allowed us to view with a new lens the works of Modernist artists whose queerness had been erased by heteronormative and patriarchal criticism. H.D., Getrude Stein, and Amy Lowell were poets who used Modernist aesthetics in order to showcase as well as celebrate their queer subjectivity. This paper attempts to show how, during the Modernist period, H.D., Gertrude Stein and Amy Lowell wrote poetry that was radical not only in terms of form but also in terms of their content. For years, the queerness of their poetry was either dismissed as unimportant, or erased for being too dangerous. This erasure of their lesbian subjectivities had resulted in a very limited understanding of their poetic projects. The queer reclamation of their poetry has allowed us to comprehend how they created poetry that subverted the phallocentric conception of erotic desire. Keywords: Modernism, queer poetics, heteronormative, desire, subjectivity. Vol. 2, Issue 4 (March 2017) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 602 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) The Queer Modernist Poetics of H.D., Gertrude Stein, and Amy Lowell Turni Chakrabarti Research Scholar Department of English University of Delhi. “... we‟re a queer lot We women who write poetry” -Amy Lowell (Galvin 26). -

Lover Lowell, Amy Lawrence

With the implementation of the exclusively heterosexual connotations of sexualr revolution^' in the 1970sromantic amorous arrangements. love seemed to take second place to lust, Dissatisfaction with the term but the AIDS crisis has helped it to make lover in its current sense suggests several a comeback. With the relentless propaga- alternatives, but these seem scarcely tion of the common coin of love through happier. Fiancd seems too old-fashioned, the mass media, gay men and lesbians and the implication that marriage will have inevitably internalized much of the follow is not appropriate for gay men and sentimental lore of heterosexual love, so lesbians. Paramour has acquired the nega- that there is now a genre of "romance" tive, judgmental connotation of a tempo- novels aimed specifically at this market. rary partner with purely physical inter- The popular psychologist Dorothy Ten- ests. An expression derived from sociology, nov attempted to introduce a new term, significant other, seems too long and pre- limerence, but it is unclear that this word tentious, while partner may imply a busi- -.ir: represents any conceptual advance; it is ness relationship, or conversely, a chance 2 - simply romantic love once again. Love, it participant in a one-nqht stand. Some seems, is a perennial theme, and one which have therefore proposed Life partner, an retains much of its mystery intact. expression now malung its way into obitu- aries as they increasingly disregard the BIBLIOGRAPHY.Edith Fischer, Amor taboo on mentioning the survivor of a und Eros: Eine Untersuchung des WortfeZdes "Liebs"im Lateinischen und homosexual couple arrangement. C!riechischen, Hildesheim: H. -

30 American Poems This Is a Sequel of Sorts to 37 American Poems, One of My First Solos

Picture here 30 American Poems This is a sequel of sorts to 37 American Poems, one of my first solos. Concentration here is on late 19th to early 20th Century works by US poets. (Summary by Bellona Times) Read by Bellona Times; total running time: 01:14:49. Dedicated Proof-Listener: April Gonzales. Meta-Coordinator & Cataloging: TriciaG. 01 - An Encounter by Robert Frost – 00:01:51 02 - Barter by Sara Teasdale – 00:01:21 03 - The Beggar Family by Morris Rosenfeld – 00:03:36 04 - California City Landscape by Carl Sandburg – 00:01:58 05 - A Chorus Girl by Edward E Cummings – 00:03:02 06 - Dinner in a Quick Lunch Room by Stephen Vincent Benet – 00:01:22 07 - The Eagle that is forgotten by Nicholas Vachel 3 Lindsay – 00:02:17 08 - A Faun in Wall Street by John Myers O'Hara – 00:01:21 09 - From a 0 Car-Window by Ruth Guthrie Harding – 00:01:10 10 - The Glory of the Day Was In Her Face by Poems American James Weldon Johnson – 00:01:05 11 - Heliodora by H.D. – 00:04:45 12 - In Time of War - Medical Unit by Edgar Lee Masters – 00:02:41 13 - Keep My Hand by Louise Driscoll – 00:00:49 14 - The Moods by Fannie Stearns Davis – 00:02:05 15 - The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes – 00:01:02 16 - Night Piece by John Dos Passos – 00:02:26 17 - Patience by American Poems American Amy Lowell – 00:01:41 18 - A Portrait of a Lady by T. -

The Lincoln Tradition in American Poetry By

THE LINCOLN TRADITION IN AMERICAN POETRY BY CELESTINE B. TEGEDER A THESIS» Submitted to the Faculty of The Creighton University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English OMAHA, 1941 Thesis Approved By TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ...... .............................. ... i Chapter I. WALT WHITMAN When Lilaos Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d. ..... 1 0, Captain, ISy Captain!.......................... 3 II. JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL Ode Recited at the Harvard Commemoration. ..... 11 III. EDWIN MARKHAM Lincoln, the Man of the People. ................... 18 IV. EDWIN ARLINGTON ROBINSON The Master........................................ 23 V. NICHOLAS VACIIEL LINDSAY Abraham Lincoln Whiles at Midnight ................. 29 The Litany of the Heroes................ 33 VI. EDGAR LEE MASTERS Autochthon. ..... ................ ...... 34 VII. JOHN GOULD FLETCHER Lincoln.................. ........................ 38 VIII. STEPHEN VINCENT BENET John Brown's Body................................. 43 IX. CONCLUSION.........................................50 Bibliography 56 INTRODUCTION New countries, such as our own United States, usually do not have a developed folk-lore nor an abundance of national legends. It is only after centuries that ancient tales and certain heroic figures become a part of the literature of a race or nation. United States history is rich in the names of outstanding characters and incidents on whioh to build such stories and even myths. We need only to read of the Colonial settlements, the Revolutionary War, the settling of the West, etc., to see that since the very beginnings of our government there have been women and men who have been prominent because of their achievements on behalf of an ideal. Names such as George ’Washington, Roger Williams, William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, Dolly Madison, Barbara Frietchie, U, S. -

Affirmation of Life and the Prospect of Death in Robinson's "Isaac and Archibald"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1971 Affirmation of Life and the Prospect of Death in Robinson's "Isaac and Archibald" Bryce Elaine Druff College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Druff, Bryce Elaine, "Affirmation of Life and the Prospect of Death in Robinson's "Isaac and Archibald"" (1971). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624734. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-h653-0w83 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AFFIRMATION o f l i f e a n d the p r o s p e c t o f d e a t h IN ROBINSON’S "ISAAC AND ARCHIBALD" A Thesis Present: ed t: o The Faculty- of* the Department of English The College of William and Mary In Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the .Degree of Master of Arts by B r' ’o e F 1. a I n e D m f f 1971 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Bryce Elaine Druff Approved, September, 1971 J. Scott Donaldson, Ph.D. feu. yisMZjU Elsa Nettels, Ph.D. ♦ $<UdbjutJ? Robertrt J. Scholnick, Ph.D AFFIRMATION OF LIFE AND THE PROSPECT OF DEATH IN ROBINSON’S "ISAAC AND ARCHIBALD" ABSTRACT The purpose of this essay is, first of all, to de termine how, if at all, the title characters of Robinson1s "Isaac and Archibald" come to terms with th© brute fact of their coming deaths, and, secondly, to speculate about Robinson’s attitude toward the two.