The Big Rethink: Positioning Pittsburgh for the Next Stage of Urban Regeneration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Y of Pitt Tsburgh H, Alleg Gheny C County Y, Penn Sylvani Ia

Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania Planning Sector 1: Troy Hill Report of Findings and Recommendations The City of Pittsburgh In Cooperation With: Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission October 2014 The Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, was made possible with funding provided by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), the City of Pittsburgh, and the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Certified Local Government program. The contents and opinions contained in this document do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program receives federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service; 1849 C Street N.W.; Washington, D.C. 20240. 2 | Page abstract Abstract This architectural inventory for the City of Pittsburgh (Planning Sector 1: Troy Hill) is in partial fulfillment of Preserve Policy 1.2, to Identify and Designate Additional Historic Structures, Districts, Sites, and Objects (City of Pittsburgh Cultural Heritage Plan, 2012). This project is the first phase of a larger undertaking which aims to ultimately complete the architectural survey for all of Pittsburgh’s Planning Sectors. -

Author: Stephan Bontrager, Director of Communications, Riverlife a Big Step Forward: Point State Park

Author: Stephan Bontrager, Director of Communications, Riverlife A Big Step Forward: Point State Park Pittsburgh’s riverfronts have undergone a long transformation from being used primarily for industry in the first half of the 20th century to the green public parks, trails, and facilities of today. The city’s riverbanks along its three rivers—the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio—are a patchwork quilt of publicly- and privately owned land, lined with industrial and transportation infrastructure that has created challenges for interconnected riverfront redevelopment across property lines. Despite the obstacles, Pittsburgh has seen a remarkable renaissance along its waterfronts. The city’s modern riverfront transformation began with the construction of Point State Park during the first “Pittsburgh Renaissance” movement of the 1940s and 50s by then- mayor David L. Lawrence. The 36-acre park at the confluence of Pittsburgh’s three rivers (the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio) was conceived as a transformational urban renewal project that would create public green space at the tip of the Pittsburgh peninsula. Championed by a bipartisan coalition of Lawrence, banker Richard King Mellon, and the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, Point State Park was created on land used primarily as a rail yard and acquired through eminent domain. Construction took several decades and the park was officially declared finished and opened to the public in 1974 with the debut of its signature feature, a 150-foot fountain at the westernmost tip of the park. After its opening, Point State Park saw near-constant use and subsequent deferred maintenance. In 2007 as part of the Pittsburgh 250th anniversary celebration, the park underwent a $35 million top-to-bottom renovation led by the Allegheny Conference, Riverlife, and the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources which owns and operates the park. -

2020 Point-In-Time Homelessness Data | August 2020 DATA Briefpage 1

Basic Needs | Allegheny County 2020 Point-in-Time Homelessness Data | August 2020 DATA BRIEFpage 1 ALLEGHENY COUNTY 2020 Point-in-Time Homelessness Data August 2020 Each year, Allegheny County participates in a national effort required by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to count the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night in January. The Point-in-Time (PIT) homeless count enumerates the sheltered (residing in emergency homeless shelters or transitional housing programs) and unsheltered (residing in places not meant for human habitation) homeless population within the County. The count is mandated by HUD to occur during the last 10 days in January every year. In 2020, the count took place on January 29. The low temperature on that night was 25 degrees Fahrenheit, which was much higher than the -7 degrees temperature for the PIT count in 2019. This data brief focuses on the January 2020 PIT count, with results of the January 2019 PIT count included for comparison. For an analysis of previous years’ PIT count data and more information about the annual data collection process, see related reports by the Allegheny County Department of Human Services (DHS).1 HUD issues guidelines for conducting PIT counts each year; variations in count methodologies over the years may contribute to increases or decreases year to year. In 2020, there were no changes in the HUD guidance in conducting PIT counts from the previous count. However, fluctuations in the number of volunteer data collectors, weather conditions and areas that were canvassed resulted in variations across time.2 Certain populations that are in unstable housing situations but not considered homeless by HUD’s definition are not included in the PIT count; for example, the PIT count does not include people who are in danger of becoming homeless in the near future, people living in doubled-up situations, or people enrolled in permanent housing programs for the formerly homeless. -

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin-submitted November 5, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I Fieldwork Methodology 3 II Prior Research Resources 5 III Allegheny Town in General 5 A. Prologue: "Allegheny is a Delaware Indian word meaning Fair Water" B. Geography 1. Neighborhood Boundaries: Past and Present C. Settlement Patterns: Industrial and Cultural History D. The Present E. Religion F. Co mmunity Centers IV Troy Hill 10 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. The Fichters 2. Czech/Bohemian D. Community Celebrations V Spring Garden/The Flats 14 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity VI Spring Hill/City View 16 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German D. Community Celebrations VII East Allegheny 18 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. Churches b. Teutonia Maennerchor 2. African Americans D. Community Celebrations E. Church Consolidation VIII North Shore 24 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Heinz House D. Ethnicity 1. Swiss-German 2. Croatian a. St. Nicholas Croatian Roman Catholic Church b. Javor and the Croatian Fraternals 3. Polish IX Allegheny Center 31 2 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Farmers' Market D. Ethnicity 1. Greek a. Grecian Festival/Holy Trinity Church b. Gus and Yia Yia's X Central Northside/Mexican War Streets 35 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. African Americans: Wilson's Bar BQ D. Community Celebrations XI Allegheny West 36 A. -

2 Mount Royal

2 MOUNT ROYAL P13 MOUNT ROYAL FLYER SERVICE NOTES MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY SERVICE MONDAY To Millvale - Etna - Shaler - Hampton - Route P13 does not operate on Saturdays, To Downtown Pittsburgh THROUGH McCandless Sundays, New Year's Day, Memorial Day, FRIDAY Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving SERVICE or Christmas. To Downtown Pittsburgh North Hills Village Target Ross Rd McKnight past Ross Park Mall Dr Ross Park Mall (at shelter) Hampton Ferguson Rd at Blvd Royal Mt at Etna Butler St opp. Freeport St Millvale North Ave at Grant Ave East Deutschtown E Ohio St past ChestnutSt Downtown St 9th at Penn Ave Downtown St 9th at Penn Ave East Deutschtown E Ohio St St Heinz at Millvale North Ave at Lincoln Ave Etna Butler St at Freeport St Hampton Ferguson Rd past Mt Royal Blvd Ross Rd McKnight opp. Ross Park Mall Dr Ross Park Mall (at shelter) Ross Rd McKnight at North Hills Village North Hills Village Target 3:53 4:00 .... 4:15 4:27 4:37 4:44 4:50 4:50 4:58 5:06 5:14 5:25 5:38 .... 5:41 5:44 4:18 4:24 .... 4:40 4:53 5:04 5:13 5:20 5:20 5:28 5:36 5:44 5:55 6:08 .... 6:11 6:14 4:48 4:54 .... 5:10 5:23 5:34 5:43 5:50 5:50 5:58 6:06 6:14 6:25 6:38 .... 6:45 6:48 5:05 5:12 .... 5:27 5:41 5:52 6:03 6:10 6:10 6:19 6:29 6:37 6:50 ... -

Urban Tree Canopy Data

Urban Tree Canopy Data % City of Pittsburgh Canopy Other Allegheny County % Canopy Neighborhoods Cover Municipalities Cover Allegheny Central 29.24 ALEPPO 70.13 Allegheny West 30.71 ASPINWALL 42.43 Allentown 40.64 AVALON 47.78 Arlington 50.06 BALDWIN 48.87 Arlington Heights 59.82 BALDWIN 49.26 Banksville 46.94 BELL ACRES 77.80 Bedford Dwellings 49.77 BELLEVUE 41.86 Beechview 50.29 BEN AVON 61.27 Beltzhoover 48.34 BEN AVON HEIGHTS 76.32 Bloomfield 18.12 BETHEL PARK 46.85 Bluff 11.94 BLAWNOX 32.90 Bon Air 52.10 BRACKENRIDGE 20.45 Brighton Heights 39.18 BRADDOCK 14.21 Brookline 38.69 BRADDOCK HILLS 52.20 California-Kirkbride 30.02 BRADFORD WOODS 81.71 Carrick 35.12 BRENTWOOD 42.22 Central Business District 7.94 BRIDGEVILLE 37.79 Central Lawrenceville 33.64 CARNEGIE 37.33 Central Northside 20.63 CASTLE SHANNON 38.53 Central Oakland 20.16 CHALFANT 40.84 Chartiers 41.86 CHESWICK 38.04 Chateau 4.56 CHURCHILL 52.85 Crafton Heights 50.40 CLAIRTON 31.96 Crawford Roberts-Hill 29.90 COLLIER 57.56 Duquesne Heights 57.26 CORAOPOLIS 41.40 East Allegheny 13.96 CRAFTON 49.45 East Carnegie 45.08 CRESCENT 68.29 East Hills 49.36 DORMONT 28.20 East Liberty 19.14 DRAVOSBURG 49.51 Elliott 53.57 DUQUESNE 23.64 Esplen 27.97 EAST DEER 64.55 Fairywood 42.78 EAST MCKEESPORT 41.40 Fineview 56.58 EAST PITTSBURGH 26.39 Friendship 25.37 EDGEWOOD 53.49 Garfield 42.66 EDGEWORTH 75.32 Glen Hazel 80.56 ELIZABETH 31.90 Greenfield 27.98 ELIZABETH TWP 63.36 Hays 81.53 EMSWORTH 48.32 Hazelwood 34.64 ETNA 35.16 Highland Park 49.23 FAWN 70.04 Homewood North 42.43 FINDLAY 50.16 -

Review of Community Assets and Priorities

Review of Community Assets and Priorities Prepared for Duquesne University’s Center for Community-Engaged Teaching and Research Strategic Planning Process January 13, 2017 Prepared by Megan Good and Jamillia Kamara Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 7 Methods 8 Background 9 Current Community Priorities and Assets 12 Common Themes 12 Community Development 13 Culture and Civic Engagement 19 Education and Skill Development 20 Health and Wellness 23 Housing 27 Public Safety 31 Transportation 33 Community Snapshots 36 Hazelwood 36 Hill District 38 Hilltop 40 Uptown 41 Sources 43 2 Acknowledgements We would like to extend our gratitude to all the community residents, leaders, stakeholders, and Duquesne University staff and faculty who shared their time, energy, stories, and insights with us. We value how generous you were with your time, connections, and honesty as we sought to better understand the rich and complex neighborhood dynamics and histories. The information we learned directly from community stakeholders provided valuable context for the community plans we reviewed, and we could not have pulled together such a comprehensive review without everyone’s support. Thank you! 3 Executive Summary Figure 1. Focus Communities Commissioned by the Center for Community-Engaged Teaching and Research (CETR) at Duquesne University, this report serves as one input to CETR’s 2016-2017 strategic planning process. As a Spiritan institution, Duquesne University is committed to a practice of community engagement which prioritizes developing authentic relationships, walking with those who have been marginalized, and being open to new perspectives and approaches. As a result, it is important for community priorities to be centered in the strategic plan. -

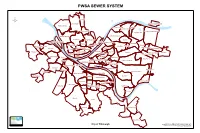

Pwsa Sewer System

PWSA SEWER SYSTEM ² Summer Hill Perry North Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar Brighton Heights Upper Lawrenceville Morningside Stanton Heights Northview Heights Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar Highland Park Marshall-Shadeland Central Lawrenceville Perry South Spring Hill-City View Garfield Marshall-Shadeland Troy Hill Esplen Lower Lawrenceville East Liberty Fineview Troy Hill California-Kirkbride Spring Garden Larimer Bloomfield Friendship Windgap Chartiers City Homewood West Central Northside R Polish Hill Sheraden E Homewood North Manchester IV East Allegheny R Y N E H Allegheny Center G Strip District Fairywood E Upper Hill Shadyside O L East Hills H Allegheny West L Homewood South IO A Bedford Dwellings R Chateau Point Breeze North IV E R Crafton Heights North Shore Middle Hill Elliott North Oakland Point Breeze Crawford-Roberts Terrace Village West End Squirrel Hill North Central Business District West Oakland Central Oakland Duquesne Heights South Shore Bluff Westwood HELA RIVER MONONGA South Oakland Ridgemont Regent Square Oakwood Squirrel Hill South Mount Washington Southside Flats East Carnegie Allentown Greenfield Southside Slopes Beltzhoover Swisshelm Park Arlington Heights Knoxville Arlington Beechview Banksville Mount Oliver Borough Hazelwood Mt. Oliver Bon Air St. Clair Glen Hazel Brookline Carrick Hays Overbrook New Homestead Lincoln Place Neither the City of Pittsburgh nor the PW&SA guarantees the accuracy of any of the information hereby made available, including but not limited to information concerning the location and condition of underground structures, and neither assumes any responsibility for any conclusions or interpretations made on the basis of such information. COP and PW&SA assume no Drawn By: JDS Date: 6/3/2016 City of Pittsburgh responsibility for any understanding or representations made by their agents or employees unless such understanding or representations are expressly set forth in a duly authorized written document, and such document expressly provides that responsibility therefore is assumed by the City or the PW&SA. -

Pittsburgh Public Schools Assignment

Pittsburgh Public Schools Assignment Jennifer Cai John Cusick Anuj Desai Zhenzhen Weng 21-393: OR II December 2014 Introduction Public schools are crucial players in the development of youth, providing equal access to educational opportunities and preparing them to be responsible citizens. 90% of school students in the United States attend public schools. There are approximately 3.1 million teachers and 49.8 million students in public schools as of fall 2014; giving an average student-to-teacher ratio of 16.1. Countless studies have shown that students learn more effectively in smaller classes. Barriers to education exist in the form of transportation. Attendance is one of the most important factors determining a child's academic achievement. Poor school performance and higher dropout rates are correlated with absenteeism. Getting to school is difficult when students do not have reliable transportation options. In addition, if a child is not eligible for school-provided transportation and has to walk to school, the route to school may be hazardous, especially for younger children. Pittsburgh Public Schools, the public school district of Pittsburgh, is the largest school district in Allegheny County and the second largest in the state of Pennsylvania. Currently 54 schools serve approximately 25,000 students in Kindergarten through Grade 12. The average student-teacher ratio for academic year 2011-2012 was 17.4. Elementary school students who live more than 1.5 miles from their schools are provided with bus transportation from the Transportation Department. Left: Map of Pittsburgh K-5 (orange) and K-8 (purple) public schools Right: Map of Pittsburgh neighborhoods In this report, we seek to assign students to schools that minimize the distance students are traveling to get to school to address some of these issues. -

The Hazelwood Neighborhood, 2010

The Hazelwood Neighborhood, 2010 Photo Credit: RIDC PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FEBRUARY 2012 www.ucsur.pitt.edu Executive Summary Hazelwood is a City of Pittsburgh neighborhood of 5,033 residents (2010 Census) located along the northern shore of the Monongahela River, approximately four miles from Downtown Pittsburgh. The neighborhood developed over 100 years ago, shaped by several steel and coke-making plants located in and around the community. In recent decades, Hazelwood has lost its manufacturing base, experienced population decline, physical abandonment, and weak demand for housing. This report presents information on the current condition of the Hazelwood community across a broad range of indicators. In this report, data for Hazelwood includes the combined totals for both the Hazelwood and Glen Hazel neighborhoods as defined by the City of Pittsburgh. Hazelwood had disproportionately smaller shares of young adults (ages 20-34), when compared to the City of Pittsburgh. While the combined population was majority-white, the community had a larger share of African American population when compared to Pittsburgh. Nearly one in three households in the two neighborhoods contained a person under age 18 compared to 1 in 5 in the City, and the majority of these households were female-headed, with no husband present. Compared to the City of Pittsburgh, households in Hazelwood had lower incomes, and residents (especially children) were more- likely to be poor. A number of indicators included in this report strongly suggest Hazelwood’s housing market suffers from a lack of demand. Prices are extremely low (sales under $10,000 are common), the pace of sales trails the City, and low levels of mortgage originations and falling homeownership rates suggest that much of the market activity is being driven by investors through cash transactions. -

2008 Annual Convention

CONVENTION JOURNAL ONE HUNDRED FORTY-THIRD ANNUAL CONVENTION of the EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF PITTSBURGH SATURDAY, OCTOBER 4th, 2008 ST. MARTIN’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH Monroeville, Pennsylvania SPECIAL CONVENTION of the EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF PITTSBURGH FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7th, 2008 MARRIOTT HOTEL, CITY CENTER Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICIAL LISTS Diocesan Personnel.................................................................................................................3 Constitutionally and Canonically Mandated Governance.........................................................4 Churches in Union with the Diocese........................................................................................8 Clergy of the Diocese............................................................................................................16 Letters Dimissory Accepted -January-December 2008 ..........................................................20 Letters Dimissory Issued -January-December 2008 ...............................................................20 Ordinations ...........................................................................................................................21 Milestone Anniversaries for Canonical Clergy ......................................................................23 PRE-CONVENTION MATERIALS AND REPORTS Agenda..................................................................................................................................24 Resolutions Presented Prior to Convention............................................................................25 -

A Menu for Food Justice

A Menu for Food Justice Strategies for Improving Access to Healthy Foods in Allegheny County Zachary Murray Emerson Hunger Fellow 16 Terminal Way Pittsburgh, PA 15219 • telephone: 412.431.8960 • fax: 412.231.8966 • w ww.justharvest.org Table of Contents The Soup- A Light Intro to Food Deserts 4 The Salad- A Food Justice Mix 6 Fishes and Loaves 11 The Main Course: A Taste of the Region 13 Methods 14 Clairton, PA 16 Millvale, PA 19 McKees Rocks and Stowe Township, PA 21 Pittsburgh East End (East Hills, Homewood, Larimer, Lincoln-Lemington- Belmar) 24 Pittsburgh Northside (Fineview, Manchester, Northview Heights, Perry South, Spring Hill, Spring Garden, Troy Hill) 27 Pittsburgh Southside Hilltop (Allentown, Arlington, Arlington Heights, Knoxville, Mt Oliver, St Clair) 33 City of Pittsburgh Sub-Analysis 36 Dessert not Deserts: Opportunities for Healthy Food in Your Community 41 Policy Recommendations 43 A Menu for Food Justice 1 Acknowledgements Just Harvest extends its profound thanks to the Congressional Hunger Center for placing Emerson Hunger Fellow Zachary Murray with Just Harvest for this project during the fall and winter of 2012- 2013. Though a short-term visitor to the Pittsburgh area for this project, Zachary ably led the as- sessment of food desert issues facing our community and is the chief author of this report. The Cen- ter’s assistance to Just Harvest over several years is deeply appreciated. We extend our thanks to the numerous individuals and organizations quoted in this report for their time, interest, and expertise. In addition, we appreciate the generosity of time and spirit showed by many store owners, managers, and employees who welcomed Zach and his team of volunteers as they assessed resources, product mix, and prices at their stores.