Megafauna and Methods New Approaches to the Study of Megafaunal Extinctions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Large Terrestrial Carnivores on Pleistocene Ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Matthew W

The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on SPECIAL FEATURE Pleistocene ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgha,1, Matthew W. Haywardb,c,d, William J. Ripplee, Carlo Melorof, and V. Louise Rothg aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bCollege of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW, United Kingdom; cCentre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa; dCentre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; eTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; fResearch Centre in Evolutionary Anthropology and Palaeoecology, School of Natural Sciences and Psychology, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 3AF, United Kingdom; and gDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338 Edited by Yadvinder Malhi, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 6, 2015 (received for review February 28, 2015) Large mammalian terrestrial herbivores, such as elephants, have analogs, making their prey preferences a matter of inference, dramatic effects on the ecosystems they inhabit and at high rather than observation. population densities their environmental impacts can be devas- In this article, we estimate the predatory impact of large (>21 tating. Pleistocene terrestrial ecosystems included a much greater kg, ref. 11) Pleistocene carnivores using a variety of data from diversity of megaherbivores (e.g., mammoths, mastodons, giant the fossil record, including species richness within guilds, pop- ground sloths) and thus a greater potential for widespread habitat ulation density inferences based on tooth wear, and dietary in- degradation if population sizes were not limited. -

Hdl 128344.Pdf

PUBLISHED VERSION Elizabeth Reed The contribution of cave sites to the understanding of Quaternary Australian megafauna records Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Speleology, Volume 1 Edition 2, 2017 / Moore, K., White, S. (ed./s), vol.1, pp.2 © 2017 Australian Speleological Federation Inc, This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike International License (CC-BY-SA). To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Individual Authors retain copyright over their work, while allowing the conference to place this unpublished work under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike which allows others to freely access, use, and share the work, with an acknowledgement of the work’s authorship and its initial presentation at the 17th International Congress of Speleology, Sydney NSW Australia.. Published version https://www.caves.org.au/resources/category/37-conference- proceedings?start=40 PERMISSIONS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 6 October 2020 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/128344 Te Contribution of Cave Sites to the Understanding of Quaternary Australian Megafauna Records. Elizabeth Reed1,2 Afliation: 1Environment Institute and School of Physical Sciences, Te University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, AUSTRALIA. 2Palaeontology department, South Australian Museum, Adelaide, South Australia. Abstract Since the frst discoveries of megafauna fossils in the Wellington Valley of New South Wales in the 1830s, caves have featured prominently in the study of Quaternary Australia. Today, most of the well-dated, strati- fed Quaternary megafauna sites are known from caves. Tis refects the relatively stable preservation environment within Australian caves, where skeletal remains may lay undisturbed for hundreds of thousands of years. -

Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids Pablo Librado, Ludovic Orlando

Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids Pablo Librado, Ludovic Orlando To cite this version: Pablo Librado, Ludovic Orlando. Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, Annual Reviews, 2021, 9 (1), 10.1146/annurev-animal-061220-023118. hal- 03030307 HAL Id: hal-03030307 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03030307 Submitted on 30 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021. 9:X–X https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-061220-023118 Copyright © 2021 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved Librado Orlando www.annualreviews.org Equid Genomics and Evolution Genomics and the Evolutionary History of Equids Pablo Librado and Ludovic Orlando Laboratoire d’Anthropobiologie Moléculaire et d’Imagerie de Synthèse, CNRS UMR 5288, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse 31000, France; email: [email protected] Keywords equid, horse, evolution, donkey, ancient DNA, population genomics Abstract The equid family contains only one single extant genus, Equus, including seven living species grouped into horses on the one hand and zebras and asses on the other. In contrast, the equine fossil record shows that an extraordinarily richer diversity existed in the past and provides multiple examples of a highly dynamic evolution punctuated by several waves of explosive radiations and extinctions, cross-continental migrations, and local adaptations. -

Archaeology Resources

Archaeology Resources Page Intentionally Left Blank Archaeological Resources Background Archaeological Resources are defined as “any prehistoric or historic district, site, building, structure, or object [including shipwrecks]…Such term includes artifacts, records, and remains which are related to such a district, site, building, structure, or object” (National Historic Preservation Act, Sec. 301 (5) as amended, 16 USC 470w(5)). Archaeological resources are either historic or prehistoric and generally include properties that are 50 years old or older and are any of the following: • Associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history • Associated with the lives of persons significant in the past • Embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction • Represent the work of a master • Possess high artistic values • Present a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction • Have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in history These resources represent the material culture of past generations of a region’s prehistoric and historic inhabitants, and are basic to our understanding of the knowledge, beliefs, art, customs, property systems, and other aspects of the nonmaterial culture. Further, they are subject to National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) review if they are historic properties, meaning those that are on, or eligible for placement on, the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). These sites are referred to as historic properties. Section 106 requires agencies to make a reasonable and good faith efforts to identify historic properties. Archaeological resources may be found in the Proposed Project Area both offshore and onshore. -

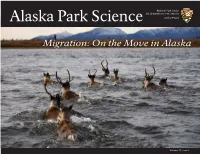

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

The Giant Alcelaphine Antelope, M. Priscus, Is One of Six Extinct Species

Palaeont. afr. , 32, 17-22 (1995) A NEW FIND OF MEGALOTRAGUS PRISCUS (ALCELAPHINI, BOVIDAE) FROM THE CENTRAL KAROO, SOUTH AFRICA by J.S. Brink!, H. de Bruiyn2, L.B. Rademeyer2 and W.A. van der Westhuizen2 lFlorisbad Quaternary Research Dept., National Museum, POBox 266, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa 2Dept. of Geology, University of the Orange Free State, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa ABSTRACT We document the occurrence of the Florisian, or late Quaternary, form of the giant a1celaphine, Megalotragus priscus, from dongas on the Ongers River, near Britstown in the central Karoo. This is significant as it confirms the occurrence of the species in the Karoo and it suggests significantly wetter environments and productive grasslands in the central Karoo in pre-Holocene times. The present-day Karoo environment did not maintain populations of large ruminant grazers similar to M. priscus, and other specialized Florisian grazers, prior to the advent of agriculture and pasture management. Aridification in recent times is the likely cause of changes in grassland quality and the local dissappearance of these animals, if not their extinction. KEY WORDS: A1celaphine evolution, Florisian mammals, Late Pleistocene extinction INTRODUCTION modem bovid fauna is the product (Vrba 1976, 1979; The giant alcelaphine antelope, M. priscus, is one of Bigalke 1978; Gentry 1978; Gentry & Gentry 1978). six extinct species which define the Florisian Land One example of this increase in end~mism is the Mammal Age (Brink 1994; Hendey 1974). The evolution of M. priscus. An ancestral form, species is known from a variety of late Quaternary M. katwinkeli, is known from East Africa and possibly sites in the interior of southern Africa as well as from some southern African Plio-Pleistocene sites, but in the Cape Ecozone in pre-Holocene times (Brink 1987; the Middle and Late Pleistocene the genus Bender & Brink 1992; Klein 1980, 1984; Klein & Megalotragus is only found in southern African fossil Cruz-Uribe 1991). -

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach

Late Quaternary Extinction of Ungulates in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reductionist's Approach Joris Peters Ins/itu/ für Palaeoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin, Universität München. Feldmochinger Strasse 7, D-80992 München, Germany AchilIes Gautier Laboratorium VDor Pa/eonlo/agie, Seclie Kwartairpaleo1ltologie en Archeozoölogie, Universiteit Gent, Krijgs/aon 2811S8, B-9000 Gent, Belgium James S. Brink National Museum, P. 0. Box 266. Bloemfontein 9300. Republic of South Africa Wim Haenen Instituut voor Gezandheidsecologie, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Capucijnenvoer 35, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium (Received 24 January 1992, revised manuscrip/ accepted 6 November 1992) Comparative osteomorphology and sta ti st ical analysis cf postcranial limb bone measurements cf modern African wildebeest (Collnochaetes), eland (Taura/ragus) and Africa n buffala (Sy" cer"s) have heen applied to reassess the systematic affiliations between these bovids and related extinct Pleistocene forms. The fossil sam pies come from the sites of Elandsfontein (Cape Province) .nd Flarisb.d (Orange Free State) in South Afrie • . On the basis of differenees in skull morphology and size of the appendicular skeleton between fossil and modern blaek wildebeest (ConlJochaeus gnou). the subspecies name anliquus, proposed earlier to designate the Pleistoeene form, ean be retained. The same taxonomie level is accepted for the large Pleistocene e1and, whieh could be named Taurolragus oryx antiquus. The long horned or giant buffa1o, Pelorovis antiquus, can be inc1uded in the polymorphous Syncerus caffer stock and could therefore be called Syncerus caffer antiquus. The ecology of Pleistocene and modern Connochaetes, Taurolragus and Syncerus is discussed. A relationship between herbivore body size and c1imate, as Bergmann's Rule predicts, could not be demonstrated. -

Ratite Molecular Evolution, Phylogeny and Biogeography Inferred from Complete Mitochondrial Genomes

RATITE MOLECULAR EVOLUTION, PHYLOGENY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY INFERRED FROM COMPLETE MITOCHONDRIAL GENOMES by Oliver Haddrath A thesis submitted in confonnity with the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science Graduate Department of Zoology University of Toronto O Copyright by Oliver Haddrath 2000 National Library Biblioth&que nationale 191 .,,da du Canada uisitions and Acquisitions et Services services bibliographiques 395 Welington Street 395. rue WdKngton Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Otîâwâ ON K1A ûN4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une iicence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant A la National Library of Canada to Bihliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, @ter, distribuer ou copies of diis thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïîm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format 61ectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette tbése. thesis nor substantial exûacts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be priated or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Ratite Molecular Evolution, Phylogeny and Biogeography Inferred fiom Complete Mitochoncîrial Genomes. Masters of Science. 2000. Oliver Haddrath Department of Zoology, University of Toronto. The relationships within the ratite birds and their biogeographic history has been debated for over a century. While the monophyly of the ratites has been established, consensus on the branching pattern within the ratite tree has not yet been reached. -

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics

Chapter 02 Biogeography and Evolution in the Tropics (a) (b) PLATE 2-1 (a) Coquerel’s Sifaka (Propithecus coquereli), a lemur species common to low-elevation, dry deciduous forests in Madagascar. (b) Ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) are highly social. PowerPoint Tips (Refer to the Microsoft Help feature for specific questions about PowerPoint. Copyright The Princeton University Press. Permission required for reproduction or display. FIGURE 2-1 This map shows the major biogeographic regions of the world. Each is distinct from the others because each has various endemic groups of plants and animals. FIGURE 2-2 Wallace’s Line was originally developed by Alfred Russel Wallace based on the distribution of animal groups. Those typical of tropical Asia occur on the west side of the line; those typical of Australia and New Guinea occur on the east side of the line. FIGURE 2-3 Examples of animals found on either side of Wallace’s Line. West of the line, nearer tropical Asia, one 3 nds species such as (a) proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus), (b) 3 ying lizard (Draco sp.), (c) Bornean bristlehead (Pityriasis gymnocephala). East of the line one 3 nds such species as (d) yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea), (e) various tree kangaroos (Dendrolagus sp.), and (f) spotted cuscus (Spilocuscus maculates). Some of these species are either threatened or endangered. PLATE 2-2 These vertebrate animals are each endemic to the Galápagos Islands, but each traces its ancestry to animals living in South America. (a) and (b) Galápagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra). These two images show (a) a saddle-shelled tortoise and (b) a dome-shelled tortoise. -

Variable Impact of Late-Quaternary Megafaunal Extinction in Causing

Variable impact of late-Quaternary megafaunal SPECIAL FEATURE extinction in causing ecological state shifts in North and South America Anthony D. Barnoskya,b,c,1, Emily L. Lindseya,b, Natalia A. Villavicencioa,b, Enrique Bostelmannd,2, Elizabeth A. Hadlye, James Wanketf, and Charles R. Marshalla,b aDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; bMuseum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; cMuseum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; dRed Paleontológica U-Chile, Laboratoria de Ontogenia, Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Chile; eDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; and fDepartment of Geography, California State University, Sacramento, CA 95819 Edited by John W. Terborgh, Duke University, Durham, NC, and approved August 5, 2015 (received for review March 16, 2015) Loss of megafauna, an aspect of defaunation, can precipitate many megafauna loss, and if so, what does this loss imply for the future ecological changes over short time scales. We examine whether of ecosystems at risk for losing their megafauna today? megafauna loss can also explain features of lasting ecological state shifts that occurred as the Pleistocene gave way to the Holocene. We Approach compare ecological impacts of late-Quaternary megafauna extinction The late-Quaternary impact of losing 70–80% of the megafauna in five American regions: southwestern Patagonia, the Pampas, genera in the Americas (19) would be expected to trigger biotic northeastern United States, northwestern United States, and Berin- transitions that would be recognizable in the fossil record in at gia. We find that major ecological state shifts were consistent with least two respects. -

Megafauna Extinction

Episode 15 Teacher Resource 2nd June 2020 Megafauna Extinction 1. Before watching the BTN story, record what you know about Students will learn more about Australian megafauna and megafauna. investigate why they became 2. What is megafauna? extinct. 3. About how many years ago did megafauna exist in Australia? a. 4,000 b. 40,000 c. 400,000 Science – Year 6 The growth and survival of living 4. Complete the following sentence. A Diprotodon was a giant things are affected by physical _________________. conditions of their environment. 5. What did palaeontologist Dr Scott Hocknull and his team discover? Science – Year 7 6. Where did they make the discovery? Scientific knowledge has changed peoples’ understanding of the 7. What did they use to create images of what the megafauna might world and is refined as new have looked like? evidence becomes available. 8. Give some examples of the megafauna species they discovered. Interactions between organisms, 9. What might have caused megafauna to become extinct? including the effects of human 10. What did you learn watching the BTN story? activities can be represented by food chains and food webs. What do you know about megafauna? As a class discuss the BTN Megafauna Extinction story and ask students to record what they learnt watching the story. Record any questions they have. Here are some questions they can use to help guide their discussion. • What does the term megafauna mean? • When did megafauna exist? • How do we know they existed? • Why did megafauna grow so big? • What might have caused Australia’s megafauna to die out? Glossary Students will brainstorm a list of key words and terms that relate to the BTN Megafauna Extinction story. -

Dietary Adaptability of Late Pleistocene Equus from West Central Mexico Alejandro H. Marín-Leyva , Daniel Demiguel , María

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript: Manuscript PALAEO8660_Marn Leyva et al _clean version.docClick here to view linked References 1 Dietary adaptability of Late Pleistocene Equus from West Central Mexico 2 3 Alejandro H. Marín-Leyva a,*, Daniel DeMiguel b,*, María Luisa García-Zepeda a, Javier 4 Ponce-Saavedra c, Joaquín Arroyo-Cabrales d, Peter Schaaf e, María Teresa Alberdi f 5 6 a Laboratorio de Paleontología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San 7 Nicolás de Hidalgo. Edif. R 2°. Piso. Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 58060, Morelia, 8 Michoacán, Mexico. 9 b Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP), Edifici Z, Campus de la UAB, C/ 10 de las Columnes s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain 11 c Laboratorio de Entomología “Biol. Sócrates Cisneros Paz”, Facultad de Biología, 12 Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Edif. B4 2º. Piso. Ciudad 13 Universitaria. C.P. 58060, Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico. 14 d Laboratorio de Arqueozoología „„M. en C. Ticul Álvarez Solórzano‟‟, Subdirección de 15 laboratorio y Apoyo Académico, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Moneda 16 #16, Col. Centro, 06060 D.F., Mexico. 17 e Instituto de Geofísica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Circuito de la 18 Investigación Científica S/N, Ciudad Universitaria, Del. Coyoacán, 04150 México, D.F., 19 México. 20 f Departamento de Paleobiología, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, José 21 Gutiérrez Abascal, 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain. 22 23 *[email protected], [email protected] 1 24 Abstract 25 Most of the Pleistocene species of Equus from Mexico have been considered to be grazers and 26 highly specialized on the basis of their craniodental features, and therefore analogous to their 27 modern relatives from an ecological point of view.