The Clinical and Genetic Features of COPD-Asthma Overlap Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Polycystic Kidney Disease 1 Like 1 Gene Variants In

HEPATOLOGY, VOL. 70, NO. 3, 2019 AUTOIMMUNE, CHOLESTaTIc aND BILIaRY DISEaSE Identification of Polycystic Kidney Disease 1 Like 1 Gene Variants in Children With Biliary Atresia Splenic Malformation Syndrome 1 1 1 2 2 2 3 John-Paul Berauer, Anya I. Mezina, David T. Okou, Aniko Sabo, Donna M. Muzny, Richard A. Gibbs, Madhuri R. Hegde, 3 3 4 5 6 7 Pankaj Chopra, David J. Cutler, David H. Perlmutter, Laura N. Bull, Richard J. Thompson, Kathleen M. Loomes, 8 8,9 10 11 11 12 Nancy B. Spinner, Ramakrishnan Rajagopalan, Stephen L. Guthery, Barry Moore, Mark Yandell, Sanjiv Harpavat, 13 14 15 16 17 18 John C. Magee, Binita M. Kamath, Jean P. Molleston, Jorge A. Bezerra , Karen F. Murray, Estella M. Alonso, 19 20 21 22 23 24 Philip Rosenthal, Robert H. Squires, Kasper S. Wang, Milton J. Finegold, Pierre Russo, Averell H. Sherker, 25 1 Ronald J. Sokol, and Saul J. Karpen ; for the Childhood Liver Disease Research Network (ChiLDReN) Biliary atresia (BA) is the most common cause of end-stage liver disease in children and the primary indication for pediatric liver transplantation, yet underlying etiologies remain unknown. Approximately 10% of infants affected by BA exhibit various laterality defects (heterotaxy) including splenic abnormalities and complex cardiac malforma- tions—a distinctive subgroup commonly referred to as the biliary atresia splenic malformation (BASM) syndrome. We hypothesized that genetic factors linking laterality features with the etiopathogenesis of BA in BASM patients could be identified through whole-exome sequencing (WES) of an affected cohort. DNA specimens from 67 BASM subjects, including 58 patient–parent trios, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases–supported Childhood Liver Disease Research Network (ChiLDReN) underwent WES. -

Diversifying Selection Between Pure-Breed and Free-Breeding Dogs Inferred from Genome-Wide SNP Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics Early Online, published on May 27, 2016 as doi:10.1534/g3.116.029678 provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository Diversifying selection between pure-breed and free-breeding dogs inferred from genome-wide SNP analysis Małgorzata Pilot,*,† Tadeusz Malewski,† Andre E. Moura,* Tomasz Grzybowski,‡ Kamil Oleński,§ Stanisław Kamiński,§ Fernanda Ruiz Fadel,* Abdulaziz N. Alagaili,** Osama B. Mohammed,** and Wiesław Bogdanowicz†,1 *School of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln, Green Lane, LN6 7DL Lincoln, UK. †Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warszawa, Poland. ‡Division of Molecular and Forensic Genetics, Department of Forensic Medicine, Ludwik Rydygier Collegium Medicum, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Skłodowskiej-Curie 9, 85- 094 Bydgoszcz, Poland. §Department of Animal Genetics, University of Warmia and Mazury, Oczapowskiego 5, 10- 711 Olsztyn, Poland. **KSU Mammals Research Chair, Department of Zoology, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2455, Riyadh 11451, Saudi Arabia. 1Corresponding author: Wiesław Bogdanowicz, Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warszawa, Poland. e-mail: [email protected] 1 © The Author(s) 2013. Published by the Genetics Society of America. Abstract Domesticated species are often composed of distinct populations differing in the character and strength of artificial and natural selection pressures, providing a valuable model to study adaptation. In contrast to pure-breed dogs that constitute artificially maintained inbred lines, free-ranging dogs are typically free-breeding, i.e. unrestrained in mate choice. Many traits in free-breeding dogs (FBDs) may be under similar natural and sexual selection conditions to wild canids, while relaxation of sexual selection is expected in pure-breed dogs. -

Structural Basis for Ca2+ Activation of the Heteromeric PKD1L3/PKD2L1

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25216-z OPEN Structural basis for Ca2+ activation of the heteromeric PKD1L3/PKD2L1 channel ✉ ✉ Qiang Su 1,2,5 , Mengying Chen3,5, Yan Wang4,5, Bin Li4,5, Dan Jing1,2, Xiechao Zhan1,2, Yong Yu 4 & ✉ Yigong Shi 1,2,3 The heteromeric complex between PKD1L3, a member of the polycystic kidney disease (PKD) protein family, and PKD2L1, also known as TRPP2 or TRPP3, has been a prototype for 1234567890():,; mechanistic characterization of heterotetrametric TRP-like channels. Here we show that a truncated PKD1L3/PKD2L1 complex with the C-terminal TRP-fold fragment of PKD1L3 retains both Ca2+ and acid-induced channel activities. Cryo-EM structures of this core hetero- complex with or without supplemented Ca2+ were determined at resolutions of 3.1 Å and 3.4 Å, respectively. The heterotetramer, with a pseudo-symmetric TRP architecture of 1:3 stoi- chiometry, has an asymmetric selectivity filter (SF) guarded by Lys2069 from PKD1L3 and Asp523 from the three PKD2L1 subunits. Ca2+-entrance to the SF vestibule is accompanied by a swing motion of Lys2069 on PKD1L3. The S6 of PKD1L3 is pushed inward by the S4-S5 linker of the nearby PKD2L1 (PKD2L1-III), resulting in an elongated intracellular gate which seals the pore domain. Comparison of the apo and Ca2+-loaded complexes unveils an unprecedented Ca2+ binding site in the extracellular cleft of the voltage-sensing domain (VSD) of PKD2L1-III, but not the other three VSDs. Structure-guided mutagenic studies support this unconventional site to be responsible for Ca2+-induced channel activation through an allosteric mechanism. -

Array Painting Reveals a High Frequency of Balanced Translocations in Breast Cancer Cell Lines That Break in Cancer-Relevant Genes

Oncogene (2008) 27, 3345–3359 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc ONCOGENOMICS Array painting reveals a high frequency of balanced translocations in breast cancer cell lines that break in cancer-relevant genes KD Howarth1, KA Blood1,BLNg2, JC Beavis1, Y Chua1, SL Cooke1, S Raby1, K Ichimura3, VP Collins3, NP Carter2 and PAW Edwards1 1Department of Pathology, Hutchison-MRC Research Centre, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK; 2Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK and 3Department of Pathology, Division of Molecular Histopathology, Addenbrookes Hospital, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK Chromosome translocations in the common epithelial tion and inversion, which can result in gene fusion, cancers are abundant, yet little is known about them. promoter insertion or gene inactivation. As is well They have been thought to be almost all unbalanced and known in haematopoietic tumours and sarcomas, therefore dismissed as mostly mediating tumour suppres- translocations and inversions can have powerful onco- sor loss. We present a comprehensive analysis by array genic effects on specific genes and play a central role in painting of the chromosome translocations of breast cancer development (Rowley, 1998). In the past there cancer cell lines HCC1806, HCC1187 and ZR-75-30. In has been an implicit assumption that such rearrange- array painting, chromosomes are isolated by flow ments are not significant players in the common cytometry, amplified and hybridized to DNA microarrays. epithelial -

Personalized Genetic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns

Journal of Personalized Medicine Review Personalized Genetic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns Olga María Diz 1,2,† , Rocio Toro 3,† , Sergi Cesar 4, Olga Gomez 5,6, Georgia Sarquella-Brugada 4,7,*,‡ and Oscar Campuzano 2,7,8,*,‡ 1 UGC Laboratorios, Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, 11009 Cadiz, Spain; [email protected] 2 Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics Department, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, 08950 Barcelona, Spain 3 Medicine Department, School of Medicine, Cádiz University, 11519 Cadiz, Spain; [email protected] 4 Arrhythmia, Inherited Cardiac Diseases and Sudden Death Unit, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, 08007 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Fetal Medicine Research Center, BCNatal-Barcelona Center for Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine (Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Deu), Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, 08950 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 6 Centre for Biomedical Research on Rare Diseases (CIBER-ER), 28029 Madrid, Spain 7 Medical Science Department, School of Medicine, University of Girona, 17003 Girona, Spain 8 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red, Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBER-CV), 28029 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.S.-B.); [email protected] (O.C.) † Equally as co-first authors. ‡ Contributed equally as co-senior authors. Citation: Diz, O.M.; Toro, R.; Cesar, Abstract: Congenital heart disease is a group of pathologies characterized by structural malforma- S.; Gomez, O.; Sarquella-Brugada, G.; tions of the heart or great vessels. -

Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping of Macrophage Atherogenic Phenotypes

QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCI MAPPING OF MACROPHAGE ATHEROGENIC PHENOTYPES BRIAN RITCHEY Bachelor of Science Biochemistry John Carroll University May 2009 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CLINICAL AND BIOANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December 2017 We hereby approve this thesis/dissertation for Brian Ritchey Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical-Bioanalytical Chemistry degree for the Department of Chemistry and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY College of Graduate Studies by ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Chairperson, Johnathan D. Smith, PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, David J. Anderson, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Baochuan Guo, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Stanley L. Hazen, MD PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Renliang Zhang, MD PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Aimin Zhou, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University Date of Defense: October 23, 2017 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my entire family. In particular, my brother Greg Ritchey, and most especially my father Dr. Michael Ritchey, without whose support none of this work would be possible. I am forever grateful to you for your devotion to me and our family. You are an eternal inspiration that will fuel me for the remainder of my life. I am extraordinarily lucky to have grown up in the family I did, which I will never forget. -

Content Based Search in Gene Expression Databases and a Meta-Analysis of Host Responses to Infection

Content Based Search in Gene Expression Databases and a Meta-analysis of Host Responses to Infection A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Francis X. Bell in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2015 c Copyright 2015 Francis X. Bell. All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge and thank my advisor, Dr. Ahmet Sacan. Without his advice, support, and patience I would not have been able to accomplish all that I have. I would also like to thank my committee members and the Biomed Faculty that have guided me. I would like to give a special thanks for the members of the bioinformatics lab, in particular the members of the Sacan lab: Rehman Qureshi, Daisy Heng Yang, April Chunyu Zhao, and Yiqian Zhou. Thank you for creating a pleasant and friendly environment in the lab. I give the members of my family my sincerest gratitude for all that they have done for me. I cannot begin to repay my parents for their sacrifices. I am eternally grateful for everything they have done. The support of my sisters and their encouragement gave me the strength to persevere to the end. iii Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES.......................................................................... vii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................ xiv ABSTRACT ................................................................................ xvii 1. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO GENE EXPRESSION............................. 1 1.1 Central Dogma of Molecular Biology........................................... 1 1.1.1 Basic Transfers .......................................................... 1 1.1.2 Uncommon Transfers ................................................... 3 1.2 Gene Expression ................................................................. 4 1.2.1 Estimating Gene Expression ............................................ 4 1.2.2 DNA Microarrays ...................................................... -

HHS Public Access Author Manuscript

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author Manuscript Author ManuscriptNature. Author ManuscriptAuthor manuscript; Author Manuscript available in PMC 2015 November 28. Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2015 May 28; 521(7553): 520–524. doi:10.1038/nature14269. Global genetic analysis in mice unveils central role for cilia in congenital heart disease You Li1,8, Nikolai T. Klena1,8, George C Gabriel1,8, Xiaoqin Liu1,7, Andrew J. Kim1, Kristi Lemke1, Yu Chen1, Bishwanath Chatterjee1, William Devine2, Rama Rao Damerla1, Chien- fu Chang1, Hisato Yagi1, Jovenal T. San Agustin5, Mohamed Thahir3,4, Shane Anderton1, Caroline Lawhead1, Anita Vescovi1, Herbert Pratt5, Judy Morgan6, Leslie Haynes6, Cynthia L. Smith6, Janan T. Eppig6, Laura Reinholdt6, Richard Francis1, Linda Leatherbury7, Madhavi K. Ganapathiraju3,4, Kimimasa Tobita1, Gregory J. Pazour5, and Cecilia W. Lo1,9 1Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 2Department of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 3Department of Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 4Intelligent Systems Program, School of Arts and Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 9Corresponding author. [email protected] Phone: 412-692-9901, Mailing address: Dept of Developmental Biology, Rangos Research Center, 530 45th St, Pittsburgh, PA, 15201. 8Co-first authors Author Contributions: Study design: CWL ENU mutagenesis, line cryopreservation, JAX strain datasheet construction: -

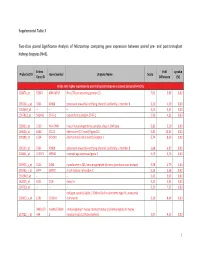

Supplemental Table 3 Two-Class Paired Significance Analysis of Microarrays Comparing Gene Expression Between Paired

Supplemental Table 3 Two‐class paired Significance Analysis of Microarrays comparing gene expression between paired pre‐ and post‐transplant kidneys biopsies (N=8). Entrez Fold q‐value Probe Set ID Gene Symbol Unigene Name Score Gene ID Difference (%) Probe sets higher expressed in post‐transplant biopsies in paired analysis (N=1871) 218870_at 55843 ARHGAP15 Rho GTPase activating protein 15 7,01 3,99 0,00 205304_s_at 3764 KCNJ8 potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 6,30 4,50 0,00 1563649_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6,24 3,51 0,00 1567913_at 541466 CT45‐1 cancer/testis antigen CT45‐1 5,90 4,21 0,00 203932_at 3109 HLA‐DMB major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM beta 5,83 3,20 0,00 204606_at 6366 CCL21 chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand 21 5,82 10,42 0,00 205898_at 1524 CX3CR1 chemokine (C‐X3‐C motif) receptor 1 5,74 8,50 0,00 205303_at 3764 KCNJ8 potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 5,68 6,87 0,00 226841_at 219972 MPEG1 macrophage expressed gene 1 5,59 3,76 0,00 203923_s_at 1536 CYBB cytochrome b‐245, beta polypeptide (chronic granulomatous disease) 5,58 4,70 0,00 210135_s_at 6474 SHOX2 short stature homeobox 2 5,53 5,58 0,00 1562642_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 5,42 5,03 0,00 242605_at 1634 DCN decorin 5,23 3,92 0,00 228750_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 5,21 7,22 0,00 collagen, type III, alpha 1 (Ehlers‐Danlos syndrome type IV, autosomal 201852_x_at 1281 COL3A1 dominant) 5,10 8,46 0,00 3493///3 IGHA1///IGHA immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1///immunoglobulin heavy 217022_s_at 494 2 constant alpha 2 (A2m marker) 5,07 9,53 0,00 1 202311_s_at -

Table S1 (Revised)

TABLE 1. LIST OF ALL PROTEINS IDENTIFIED SORTED BY GENE NAME Membrane Probability Accession GI Number Protein Name Entrez Gene Name # of Expts Peptides Fraction score number SV 0.82 10947122 NP_064693.1 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C, member 9 isoform SUR2B ABCC9 1 EVQM[147]GAVKK SSILIMDEATASIDMATENILQK PM 0.99 21431817 P49597 Protein phosphatase 2C ABI1 (PP2C) (Abscisic acid-insensitive 1) ABI1 1 KEGKDPAAM[147]SAAEYLSK KEGKDPAAMSAAEYLSK PM 0.82 231504 P30172 ACTIN 100,ACTIN 101 AC100 1 AVFPSIVGRPR AGFAGDDAPR VSPDEHPVLLTEAPLNPK SV 1 4501853 NP_001598.1 acetyl-Coenzyme A acyltransferase 1 ACAA1 1 SITVTQDEGIRPSTTMEGLAK PM 0.86 4501855 NP_001084.1 acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 1 VIQVENSHIILTGASALNK M[147]TVPISITNPDLLR MTVPISITNPDLLR EAISNMVVALK SV 0.75 38505218 NP_115545.3 putative acyl-CoA dehydrogenase ACAD11 1 QHSMILVPMNTPGVK QHSM[147]ILVPM[147]NTPGVK PM 1 113018 P08503 Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium-chain specific, mitochondrial precursor (MCAD) ACADM 1 VPKENVLIGEGAGFK PM 0.99 4557237 NP_000010.1 acetyl-Coenzyme A acetyltransferase 1 precursor ACAT1 1 DGLTDVYNK SV 0.89 9998948 NP_064718.1 amiloride-sensitive cation channel 3 isoform c ACCN3 1 DNEETPFEVGIR PM 1 7662238 NP_055792.1 apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer 1 ACIN1 1 VDRPSETKTEEQGIPR CEAEEAEPPAATQPQTSETQTSHL SV 0.76 30089972 NP_004026.2 acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 ACOX1 1 EIGTHKPLPGITVGDIGPK TSNHAIVLAQLITK PM 1 16445033 NP_443189.1 ACRC protein; putative nuclear protein ACRC 1 FAKIQIGLKVCDSADR SV 0.93 27477105 NP_055977.3 lipidosin ACSBG1 1 EVEPTSHMGVPR MELPIISNAM[147]LIGDQR -

Functional Domains and Evolutionary History of the PMEL and GPNMB Family Proteins

molecules Article Functional Domains and Evolutionary History of the PMEL and GPNMB Family Proteins Paul W. Chrystal 1,2,† , Tim Footz 1,† , Elizabeth D. Hodges 2, Justin A. Jensen 2, Michael A. Walter 1,* and W. Ted Allison 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Medical Genetics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2R3, Canada; [email protected] (P.W.C.); [email protected] (T.F.) 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T7Y 1C4, Canada; [email protected] (E.D.H.); [email protected] (J.A.J.) 3 Centre for Prions & Protein Folding Disease, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2M8, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.A.W.); [email protected] (W.T.A.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: The ancient paralogs premelanosome protein (PMEL) and glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B (GPNMB) have independently emerged as intriguing disease loci in recent years. Both proteins possess common functional domains and variants that cause a shared spectrum of overlapping phenotypes and disease associations: melanin-based pigmentation, cancer, neurode- generative disease and glaucoma. Surprisingly, these proteins have yet to be shown to physically or genetically interact within the same cellular pathway. This juxtaposition inspired us to compare and contrast this family across a breadth of species to better understand the divergent evolution- ary trajectories of two related, but distinct, genes. In this study, we investigated the evolutionary history of PMEL and GPNMB in clade-representative species and identified TMEM130 as the most Citation: Chrystal, P.W.; Footz, T.; ancient paralog of the family. By curating the functional domains in each paralog, we identified Hodges, E.D.; Jensen, J.A.; Walter, PMEL M.A.; Allison, W.T. -

Membranes of Human Neutrophils Secretory Vesicle Membranes And

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 30, 2021 is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 25 of which you can access for free at: 2008; 180:5575-5581; ; from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication J Immunol doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5575 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/180/8/5575 Comparison of Proteins Expressed on Secretory Vesicle Membranes and Plasma Membranes of Human Neutrophils Silvia M. Uriarte, David W. Powell, Gregory C. Luerman, Michael L. Merchant, Timothy D. Cummins, Neelakshi R. Jog, Richard A. Ward and Kenneth R. McLeish cites 44 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2008/04/01/180.8.5575.DC1 This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/180/8/5575.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* • Why • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2008 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 30, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Comparison of Proteins Expressed on Secretory Vesicle Membranes and Plasma Membranes of Human Neutrophils1 Silvia M.