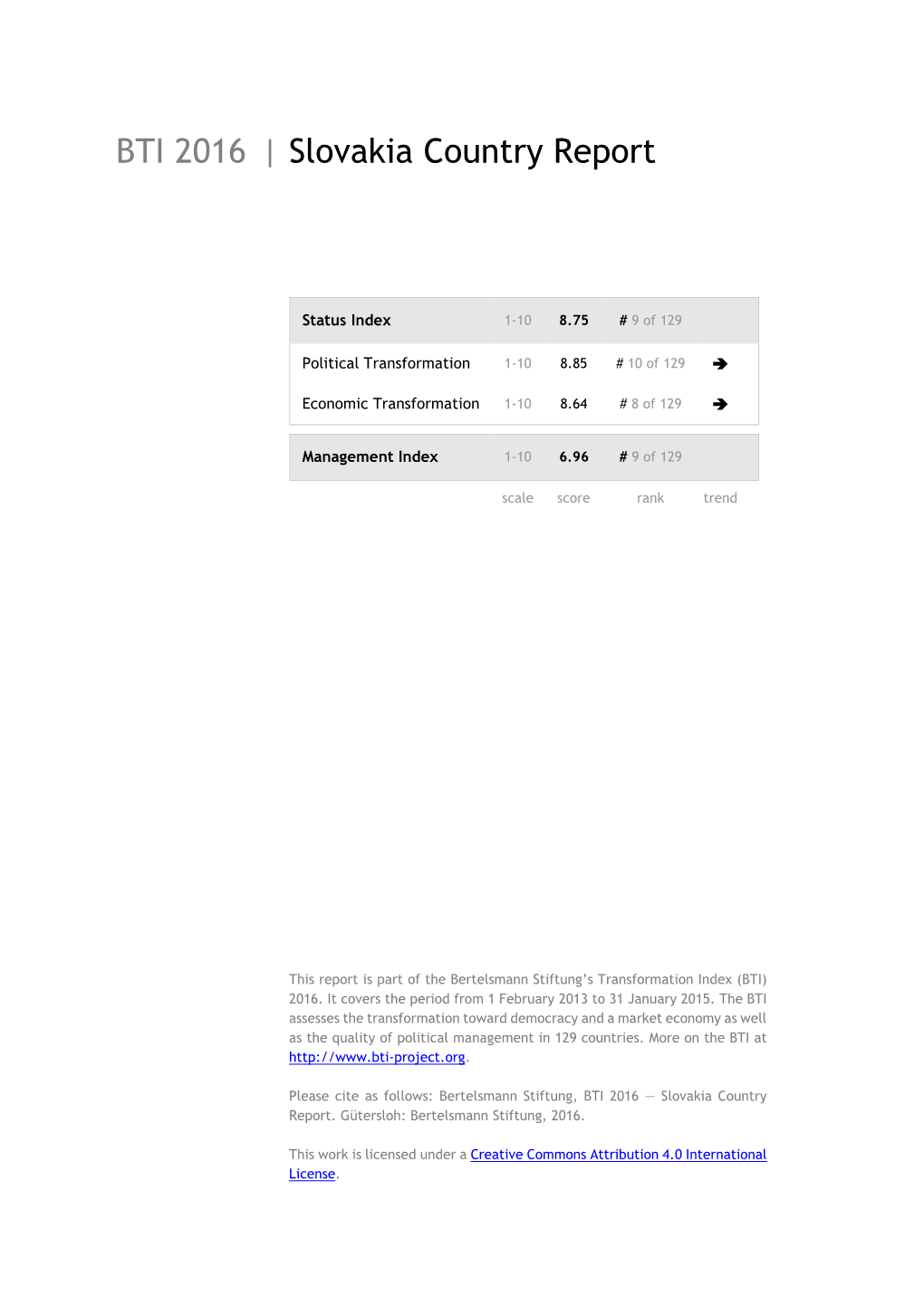

Slovakia Country Report BTI 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Influence Matrix Slovakia

J A N U A R Y 2 0 2 0 MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX: SLOVAKIA Government, Politics and Regulation Author: Marius Dragomir 2nd updated edition Published by CEU Center for Media, Data and Society (CMDS), Budapest, 2020 About CMDS About the author The Center for Media, Data and Society Marius Dragomir is the Director of the Center (CMDS) is a research center for the study of for Media, Data and Society. He previously media, communication, and information worked for the Open Society Foundations (OSF) policy and its impact on society and for over a decade. Since 2007, he has managed practice. Founded in 2004 as the Center for the research and policy portfolio of the Program Media and Communication Studies, CMDS on Independent Journalism (PIJ), formerly the is part of Central European University’s Network Media Program (NMP), in London. He School of Public Policy and serves as a focal has also been one of the main editors for PIJ's point for an international network of flagship research and advocacy project, Mapping acclaimed scholars, research institutions Digital Media, which covered 56 countries and activists. worldwide, and he was the main writer and editor of OSF’s Television Across Europe, a comparative study of broadcast policies in 20 European countries. CMDS ADVISORY BOARD Clara-Luz Álvarez Floriana Fossato Ellen Hume Monroe Price Anya Schiffrin Stefaan G. Verhulst Hungary, 1051 Budapest, Nador u. 9. Tel: +36 1 327 3000 / 2609 Fax: +36 1 235 6168 E-mail: [email protected] ABOUT THE MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX The Media Influence Matrix Project is run collaboratively by the Media & Power Research Consortium, which consists of local as well as regional and international organizations. -

Freedom House

7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 Slovakia 88 FREE /100 Political Rights 36 /40 Civil Liberties 52 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 88 /100 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. TOP https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/freedom-world/2020 1/15 7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House Overview Slovakia’s parliamentary system features regular multiparty elections and peaceful transfers of power between rival parties. While civil liberties are generally protected, democratic institutions are hampered by political corruption, entrenched discrimination against Roma, and growing political hostility toward migrants and refugees. Key Developments in 2019 In March, controversial businessman Marian Kočner was charged with ordering the 2018 murder of investigative reporter Ján Kuciak and his fiancée. After phone records from Kočner’s cell phone were leaked by Slovak news outlet Aktuality.sk, an array of public officials, politicians, judges, and public prosecutors were implicated in corrupt dealings with Kočner. Also in March, environmental activist and lawyer Zuzana Čaputová of Progressive Slovakia, a newcomer to national politics, won the presidential election, defeating Smer–SD candidate Maroš Šefčovič. Čaputová is the first woman elected as president in the history of the country. Political Rights A. Electoral Process A1 0-4 pts Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 TOP Slovakia is a parliamentary republic whose prime minister leads the government. There is also a directly elected president with important but limited executive powers. In March 2018, an ultimatum from Direction–Social Democracy (Smer–SD), a https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/freedom-world/2020 2/15 7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House junior coalition partner, and center-right party Most-Híd, led to the resignation of former prime minister Robert Fico. -

Penta Holding Limited /Annual Report 2007

Penta Holding Limited / Annual Report 2007 It doesn´t take just seeding – it takes more to have a good harvest. We know how. With the right care a single seed can be grown into a strong plant and the whole fi eld can fl ourish from its fruitage. Contents 04 Tombstones 06 Financial Highlights 08 Our Profi le 10 Director’s Statement 14 Holding Structure 16 Partners 18 Operational Structure 20 Penta’s Key Investments 30 Management Discussion & Analysis 40 Penta Holding Limited 50 Penta Investments Limited 60 Contacts Completed Investments ADAST, a.s. Letisko Košice, a.s. Slovenské lodenice, a.s. manufacturing transport manufacturing Czech Republic Slovakia Slovakia Česká konsolidační agentura Reštitučný investičný fond, a.s. Slovnaft, a.s. fi nancial investment fund oil and gas Czech Republic Slovakia Slovakia Severomoravské vodovody Drôtovňa Hlohovec, a.s. a kanalizace Ostrava a.s. Tento, a.s. manufacturing utilities manufacturing Slovakia Czech Republic Slovakia Elektrovod Bratislava, a.s. Slovenská plavba a prístavy, a.s. VÚB Kupón utilities transport investment fund Slovakia Slovakia Slovakia Chemolak, a.s. Slovenská poisťovňa, a.s. manufacturing insurance Slovakia Slovakia Real Estate Projects Digital Park, a.s. The Port, a.s. real estate real estate Slovakia Slovakia Investments in Progress Mobile Entertainment Company, a.s./ AERO Vodochody a.s. MOBILKING VSŽ - slovenské investičné družstvo aerospace telecommunications metal industry Czech Republic Poland Slovakia Alpha Medical Ventures, s.r.o. MobilKom, a.s./U:fon ZSNP, a.s. health care telecommunications metal industry Slovakia Czech Republic Slovakia AVC, a.s. PM Zbrojníky, a.s. Žabka manufacturing food processing retail Slovakia Slovakia Poland, Czech Republic Dr. -

Unter Europäischen Sozialdemokraten – Wer Weist Den Weg Aus Der Krise? | Von Klaus Prömpers Von Der Partie

DER HAUPTSTADTBRIEF 23. WOCHE AM SONNTAG 09.JUNI 2019 DIE KOLUMNE Rückkehr zu außenpolitischen Fundamenten AM SONNTAG Die Reise des Bundespräsidenten nach Usbekistan zeigt, wie wichtig die Schnittstelle zwischen Europa und Asien ist | Von Manfred Grund und Dirk Wiese Sonstige Vereinigung ie wichtig Zentralasien für Mirziyoyev ermutigen, „auf diesem Weg Europa ist, hat Frank-Walter entschlossen weiterzugehen“. Steinmeier WSteinmeier früh erkannt. Im und Mirziyoyev kannten sich bereits vom November 2006 bereiste er als erster Au- Berlin-Besuch des usbekischen Präsidenten GÜNTER ßenminister aus einem EU-Mitgliedsland im Januar 2019 – dem ersten eines usbeki- BANNAS BERND VON JUTRCZENKA/DPABERND VON alle fünf zentralasiatischen Staaten. Er schen Staatsoberhaupts seit 18 Jahren. PRIVAT wollte damals ergründen, wie die Euro- Die Bedeutung Zentralasiens für Europa päische Union mit der Region zusammen- hat seit 2007 weiter zugenommen. Zugleich ist Kolumnist des HAUPTSTADTBRIEFS. Bis März 2018 war er Leiter der Berliner arbeiten könne, die – so war ihm schon hat sich die geopolitische Schlüsselregion – Redaktion der Frankfurter Allgemeinen damals klar – „einfach zu wichtig ist, als Usbekistan zeigt es – grundlegend verändert. Zeitung. Hier erinnert er an die politisch dass wir sie an den Rand unseres Wahr- Die EU-Kommission und die Hohe Vertrete- vielgestaltige Gründungsphase der nehmungsspektrums verdrängen.“ Ein rin der EU für Außen- und Sicherheitspoli- Grünen vor 40 Jahren. halbes Jahr später nahm die EU auf Initi- tik haben diesen Entwicklungen Rechnung ative der deutschen Ratspräsidentschaft getragen und am 15. Mai eine überarbeitete die Strategie „EU und Zentralasien – eine Zentralasienstrategie vorgestellt. Unter dem nfang kommenden Jahres wer- Partnerschaft für die Zukunft“ (kurz: EU- Titel „New Opportunities for a Stronger Part- Aden die Grünen ihrer Grün- Zentralasienstrategie) an. -

Pharma Drives Economic Growth in Central Europe

What the doctor ordered: Pharma drives economic growth in Central Europe Leveraging location, low costs, and strong legacy companies with a skilled labour pool, the pharmaceutical industry is a quiet success story in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The sector is a major contributor to exports and R&D spending in several countries, and has become a magnet for M&A deals in recent years. International pharmaceutical companies have a strong manufacturing presence across the CEE region, producing and exporting a wide range of products. US multinational Teva, for example, gained CEE assets – including two generics factories in Bulgaria and oncology drugs facility in Romania – when it acquired Allergan’s Actavis Generics in 2016. Meanwhile, Sanofi announced earlier this year that it would carve out its active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) business as a standalone company, creating the world’s second-largest API manufacturer.[1]Its production facilities will include a plant in Ujpest, Hungary. Basel-based Novartis has invested nearly €2bn in Slovenia since 2003, largely through its generics and biosimilars business Sandoz, which has four locations in the country. And in 2019 Sandoz itself announced a deal for the global commercialisation and distribution of a biosimilar to combat multiple sclerosis, to be developed and manufactured by Gdansk-based Polphama Biologics.[2] An export edge Generics manufacturing in particular relies on three factors: low costs, reliable supply chains, and a skilled workforce – including a regulatory team able to spot products coming off patent. CEE has all these factors, making it a prime manufacturing location for the rest of Europe and beyond. -

Strengthening Social Democracy in the Visegrad Countries Limits and Challenges Faced by Smer-SD Darina Malová January 2017

Strengthening Social Democracy in the Visegrad Countries Limits and Challenges Faced by Smer-SD Darina Malová January 2017 Smer-Sociálna Demokracia (Smer-SD) was founded in December 1999 as a result of the defection from the post-communist Party of the Democratic Left (SDĽ) by Robert Fico, the party’s most popular politician at that time. Smer-SD is the largest mainstream party in Slovakia, with stable support. Its mixed, mostly traditional left- -wing (bread-and-butter) appeals and selected social policies have proven popular with the electorate. Robert Fico has remained the key person in Smer-SD. He is the uncontested leader, exercising a large amount of control over the party organisation, including territorial party units, selection of candidates for public elections and many key party decisions. Smer-SD is, in terms of its rhetoric, a traditional socialist party, speaking to the poorer strata, advocating a welfare state, but in reality the party pursues fairly strict austerity policies with occasional ‘social packages’. Unlike Western social democratic parties the leaders of Smer-SD are prone to using national and populist appeals. In terms of ideology (like many other parties in Slovakia) Smer-SD is a typical catch-all party with centrist and partly inconsistent party programmes, appeals to ever wider audiences, and the pursuit of votes at the expense of ideology. The weakest points in the public perception of the party are Smer-SD’s murky relations with oligarchs and high levels of corruption. Strengthening Social Democracy in the Visegrad Countries Limits and Challenges Faced by Smer-SD Darina Malová January 2017 ISBN 978-80-87748-32-9 (online) Contents 1. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Supplementary File

Online-Appendix for the paper: Electoral behavior in a European Union under stress Table A1: Eurosceptic Parties in the 2014 European Parliament election Country Parties Austria EU Stop, Europe Different, Austrian Freedom Party Belgium Workers Party of Belgium, Flemish Interest Bulgaria Bulgaria Without Censorship, National Front, Attack Croatia Croatian Party of Rights Cyprus Progressive Party of the Working People, National Popular Front Czech Dawn of Direct Democracy, Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia, Party of Republic Free Citizens Denmark Danish People’s Party, People’s Movement against the EU Estonia Conservative People’s Party of Estonia Finland True Finns France Left Front, Arise the Republic, National Front Germany National Democratic Party of Germany, The Left, Alternative for Germany Greece Communist Party of Greece, Coalition of the Radical Left, Independent Greeks, Popular Orthodox Rally, Golden Dawn Hungary FIDESZ-KDNP Alliance, Jobbik Ireland Ourselves Alone Italy Left Ecology Movement, Northern League, Five Star Movement Latvia Green and Farmers’ Union, National Independence Movement of Latvia Lithuania Order and Justice, Election Action of Lithuania’s Poles Luxembourg Alternative Democratic Reform Party Malta none applicable Netherlands Socialist Party, Coalition CU—SGP, Party of Freedom Poland Congress of the New Right, United Poland, Law and Justice Portugal Left Bloc, Unified Democratic Coalition Romania Greater Romania Party, People’s Party—Dan Dianconescu Freedom and Solidarity, Ordinary People and Independent -

State of Populism in Europe

2018 State of Populism in Europe The past few years have seen a surge in the public support of populist, Eurosceptical and radical parties throughout almost the entire European Union. In several countries, their popularity matches or even exceeds the level of public support of the centre-left. Even though the centre-left parties, think tanks and researchers are aware of this challenge, there is still more OF POPULISM IN EUROPE – 2018 STATE that could be done in this fi eld. There is occasional research on individual populist parties in some countries, but there is no regular overview – updated every year – how the popularity of populist parties changes in the EU Member States, where new parties appear and old ones disappear. That is the reason why FEPS and Policy Solutions have launched this series of yearbooks, entitled “State of Populism in Europe”. *** FEPS is the fi rst progressive political foundation established at the European level. Created in 2007 and co-fi nanced by the European Parliament, it aims at establishing an intellectual crossroad between social democracy and the European project. Policy Solutions is a progressive political research institute based in Budapest. Among the pre-eminent areas of its research are the investigation of how the quality of democracy evolves, the analysis of factors driving populism, and election research. Contributors : Tamás BOROS, Maria FREITAS, Gergely LAKI, Ernst STETTER STATE OF POPULISM Tamás BOROS IN EUROPE Maria FREITAS • This book is edited by FEPS with the fi nancial support of the European -

PRESS RELEASE Goetzpartners Advised Penta Exclusively in the Acquisition of Lloyds Pharmacies and a Pharmaceutical Distributor in the Czech Republic

PRESS RELEASE goetzpartners advised Penta exclusively in the acquisition of Lloyds pharmacies and a pharmaceutical distributor in the Czech Republic Penta Investments, the Central European investment group, has agreed with Celesio AG to acquire its Lloyds pharmacy chain and Gehe wholesale distributor. The purchase price reached EUR 84.5 million. Lloyds operates 55 pharmacies and is the third largest pharmacy chain in the Czech Republic, while Gehe is the fourth biggest wholesale pharmaceutical distributor in the Czech Republic. The transaction is subject to the Czech antitrust authority clearance. goetzpartners acted as exclusive financial advisor to Penta in this transaction. The Lloyds pharmacies will be integrated into Ceska lekarna, a.s, which operates the Dr. Max pharmacy chain on the Czech market. "We are consolidating pharmacies in Central Europe through Dr. Max and its local platforms. The Lloyds pharmacies and an important distributor Gehe have therefore been a very reasonable target for us. We strongly believe that market consolidation in the pharmacy sector significantly contributes to better quality and accessibility of services for patients," said Václav Jirků, Investment Director at Penta. "The integration of Lloyds pharmacies will support our efforts to become the most accessible pharmacy chain in terms of price and location, while the Gehe acquisition is an opportunity to implement our successful Dr. Max business model to the wholesale market. We plan to attract Gehe's independent clients with strategies similar to those we used in the retail market, namely competitive price and services," said Pavel Vajskebr, Dr. Max's CEO. “By this acquisition Penta significantly contributes to strategically improve pharmaceutical distribution in Central Europe, said Dr. -

D6-2 Slovakia

EU Grant Agreement number: 290529 Project acronym: ANTICORRP Project title: Anti-Corruption Policies Revisited Work Package: WP 6 Media and corruption Title of deliverable: D 6.2 Case studies on corruption involving journalists Case studies on corruption involving journalists: Slovakia Due date of deliverable: 31 August, 2016 Actual submission date: 31 August, 2016 Author: Andrej Školkay (SKAMBA) Contributors: Alena Ištoková, Ľubica Adamcová, Dagmar Kusá, Juraj Filin, Martin Matis, Veronika Džatková, Ivan Kuhn, Gabriela Mezeiová and Silvia Augustínová Organization name of lead beneficiary for this deliverable: UNIPG, UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PERUGIA Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Co Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) This project has been supported also by the Slovak Research and Development Agency DO7RP-0039-11 The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) only and do not reflect any collective opinion of the ANTICORRP consortium, nor do they reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the European Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction p. 3 2. Case study 1: Can a “Lone Wolf” quasi-investigative journalist substitute p. 9 low functionality of the law enforcing system? 3. Case study 2: “Dangerous liaisons” between politicians and journalists in the context p. -

THE JUNCKER COMMISSION: an Early Assessment

THE JUNCKER COMMISSION: An Early Assessment John Peterson University of Edinburgh Paper prepared for the 14th Biennial Conference of the EU Studies Association, Boston, 5-7th February 2015 DRAFT: Not for citation without permission Comments welcome [email protected] Abstract This paper offers an early evaluation of the European Commission under the Presidency of Jean-Claude Juncker, following his contested appointment as the so-called Spitzencandidat of the centre-right after the 2014 European Parliament (EP) election. It confronts questions including: What will effect will the manner of Juncker’s appointment have on the perceived legitimacy of the Commission? Will Juncker claim that the strength his mandate gives him license to run a highly Presidential, centralised Commission along the lines of his predecessor, José Manuel Barroso? Will Juncker continue to seek a modest and supportive role for the Commission (as Barroso did), or will his Commission embrace more ambitious new projects or seek to re-energise old ones? What effect will British opposition to Juncker’s appointment have on the United Kingdom’s efforts to renegotiate its status in the EU? The paper draws on a round of interviews with senior Commission officials conducted in early 2015 to try to identify patterns of both continuity and change in the Commission. Its central aim is to assess the meaning of answers to the questions posed above both for the Commission and EU as a whole in the remainder of the decade. What follows is the proverbial ‘thought piece’: an analysis that seeks to provoke debate and pose the right questions about its subject, as opposed to one that offers many answers.