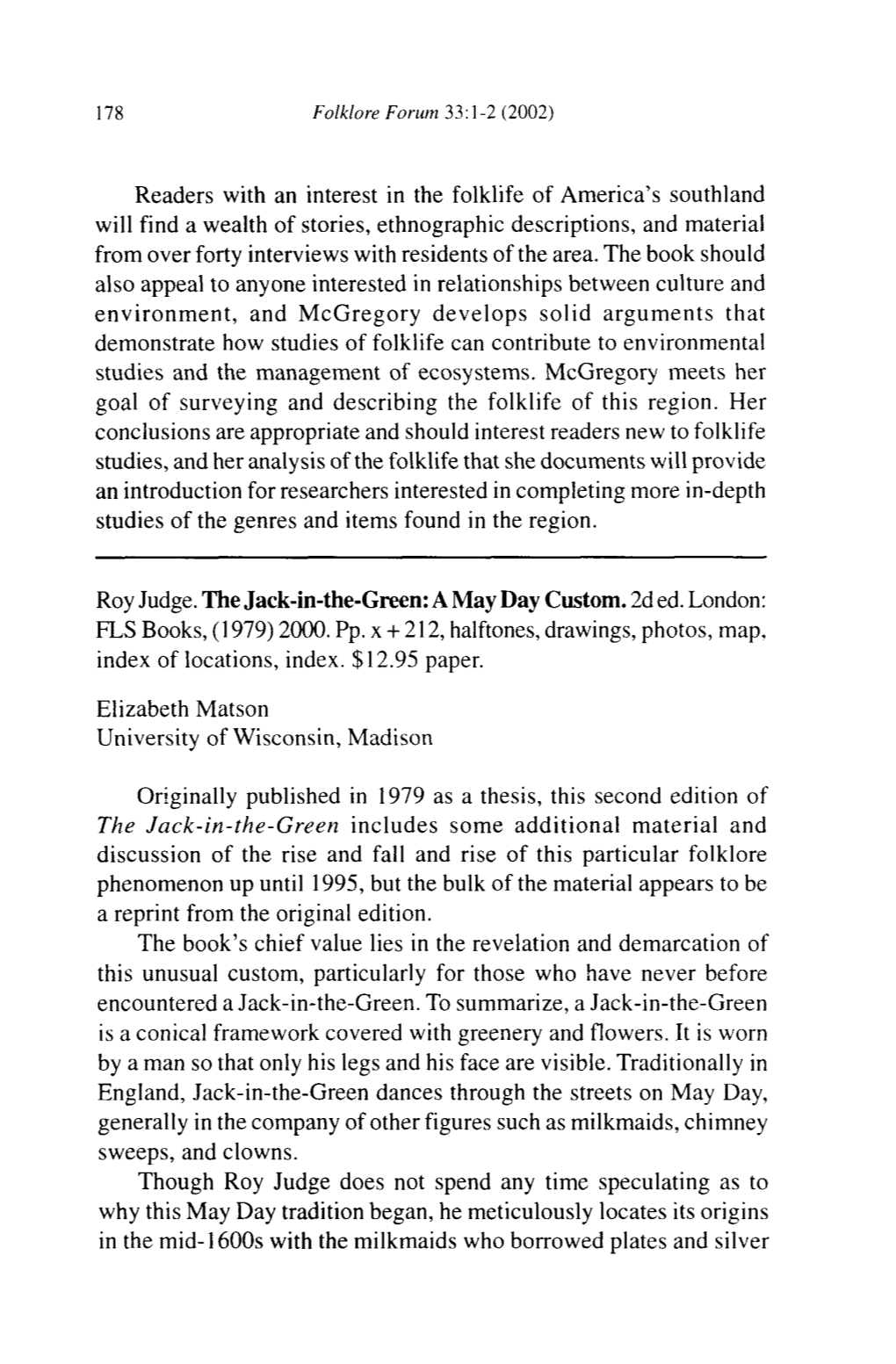

Roy Judge. the Jack-In-The-Green:A May Day Custom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN Guide 2015 Summary

Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN guide 2015 Summary Selected establishments 3998 Hotels & guesthouses 1756 Particularly pleasant establishments l to h...I 219 Guesthouses I 556 Bib Hotels * (Good accommodation at moderate price) 66 209 Hotels with Spas L Restaurants 2242 Particularly pleasant establishments ö to A 188 Bib Gourmands = (Good food at moderate price) 155 Of which new N 26 Pubs A 592 o (Exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey) 4 mm (Excellent cooking, worth a detour) 21 142 m (Very good cooking in its category) Of which new N 14 1 Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN guide 2015 Starred establishments o Exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey Town County Establishment Comfort Chef England Bray Windsor & Waterside Inn õ Alain Roux/Fabrice Uhryn Maidenhead Bray Windsor & Fat Duck ô Heston Blumenthal/Jonny Maidenhead Lake London Kensington and Chelsea Gordon Ramsay õ Clare Smyth Chelsea Westminster (City Mayfair Alain Ducasse at The ö Jocelyn Herland of) Dorchester mm Excellent cooking, worth a detour Town County Establishment Comfort England Bagshot Surrey Michael Wignall at The Latymer õ Cambridge Cambridgeshire Midsummer House ô Chagford Devon Gidleigh Park õ Cheltenham Gloucestershire Le Champignon Sauvage ô Grange-over-Sands Cumbria L'Enclume ó London Kensington & Chelsea North Kensington Ledbury ô Westminster (City of) Belgravia Marcus õ Hyde Park & Knightsbridge Dinner by Heston Blumenthal ó Mayfair Sketch (The Lecture Room & Library) õ Mayfair Hélène Darroze at The Connaught õ Mayfair Le Gavroche õ Mayfair Square -

Jack in the Green;

JACK IN THE GREEN; OR, HINTS ON ETIQUETTE, An Original Farce, in the Vulgar Tongue. BY MARK LEMON, AUTHOR OF " GWYNETH VAUGHAN," "HEARTS ARE TRUMPS," " WHAT WILL THE WORLD SAY," " DOMESTIC ECONOMY," &C. &C. T. HAILES LACY, WELLINGTON STREET, STRAND, LONDON. First performed at the Royal Adelphi Theatre, on Thursday, May 23, 1850. MR. DURHAM MR. BOYCE. JONAS WHITE (a chimney sweep) .... MR. P. BEDFORD. FLUEY (his man) MR. J. SANDERS. BOB BRYANSTONE (a small coal dealer) MR. WRIGHT. JOHN MR. LINTON. THOMAS MR. BROWN. MISS DURHAM Miss E. HARDING. MRS. WHITE MRS. LAWS. EMMA WHITE Miss E. CHAPLIN . Time of Representation—50 Minutes. Costumes, MR. DURHAM.—Plain morning dress. JONAS WHITE.—Velveteen knee breeches and coat.' FLUEY.—Ditto. BRYANSTONE.—First dress.—Cord jacket and trousers; fantail hat. Second dress.—Very gaudy waistcoat; blue coat and brass buttons ; knee breeches, shoes, and gaiters. Miss DURHAM.—First dress.— Morning robe. Second.— Rich dress. MRS. WHITE.—Common costume of the day EMMA.—Ditto ; gaudy shawl and bonnet. JACK IN THE GREEN. SCENE I. Interior of JONAS WHITE'S house. PETER FLUEY is stand- ing on his hands against the wall. JONAS is polishing a brass ladle. EMMA is sewing the leaves on a " Jack in the Green," which is placed on a table R. MRS. WHITE is em- broidering a coat with gilt paper L. The tables are covered with pieces of ribbons, coloured paper, &c. FLU. I say, master, I think I can walk now. JON. Then try, Fluey, try ; your legs and arms was given you for that purpose. FLU. -

Being an Occasional Publication of the Morris Ring Volume V, Number 1

The Morris Dancer Being an occasional publication of the Morris Ring Volume V, Number 1. July, 2012. View of the Iron Bridge, Shropshire. by G. Robertson and J. Fittler. Table of Contents ____________________________________ An introduction to the new editors……3 Further Reflections on Rural Morris Dance Sets in the Metropolis by Keith Chandler………………………………………….....4 The Immortal Memory by Ivor Allsop…...6 Revival of Morris Dancing in Kingston at the 1911 Coronation of King George V by Colin Messer………………………………………15 The Morris ring as Fraternity BY Mac mccoig…………………………………………….....24 Book Review: A Matter of Degree by Brian Tasker……………………………………….…........29 Helen Karpeles, Cecil Sharp, Douglas Kennedy, Maud Karpeles 2 Welcome to the latest edition of the Morris Dancer. Your co-editors for this glorious venture: Mac McCoig I currently dance with Uttoxeter Heart of Oak Morris Men. I learned to dance with Winchester MM under the eagle eye of Lionel Bacon during the 1970s. A degree in Fine Art (Painting), a career in Social Housing and a parallel career as an officer in the Territorial Army may not, at first glance, equip one to be the editor of a journal devoted to research papers on Morris Dancing. However, I have a keen interest in Morris-related research and 40 years dancing experience and this, plus a request from Peter Halfpenny, has prompted me to become involved with the production of the Morris Dancer. Contact me: Mac McCoig 8 Redhills Eccleshall Stafford ST21 6JW UK [email protected] Andrew Bullen I currently dance with Pullman Morris and Sword, in the Pullman neighbourhood in Chicago in the U.S. -

Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN Guide 2015 Bib Gourmands =

Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN guide 2015 Bib Gourmands = N: New Bib Gourmands 2015 Town County Establishment England Aldeburgh Suffolk Lighthouse Belbroughton Worcestershire The Queens Blackpool/ Thornton Blackpool Twelve Brighton and Hove Brighton and Hove Chilli Pickle Brighton and Hove Brighton and Hove 64° N Bristol Bristol Flinty Red Bristol/ Long Ashton Somerset Bird in Hand Britwell Salome Oxfordshire Red Lion Bruntingthorpe Leicestershire The Joiners Bruton Somerset At The Chapel Bury Greater Manchester Waggon Bury St Edmunds Suffolk Pea Porridge Cheltenham Gloucestershire The Tavern Chester Chester Joseph Benjamin Christchurch Dorset Kings Arms Cirencester Gloucestershire Made by Bob N Clyst Hydon Devon Five Bells Inn N Cookham Windsor and Maidenhead White Oak Darlington/ Hurworth on Tees Darlington Bay Horse Derby Derby Ibérico World Tapas N Donhead St Andrew Wiltshire The Forester Drighlington West Yorkshire Prashad Droxford Hampshire Bakers Arms Durham Durham Bistro 21 East Haddon Northamptonshire Red Lion Exeter/ Rockbeare Devon Jack in the Green Gedney Dyke Lincolnshire Chequers Gerrards Cross Buckinghamshire Three Oaks N Hastings and St Leonards East Sussex St Clements Hitchin Hertfordshire hermitage rd Hunsdon Hertfordshire Fox and Hounds Ingham Norfolk Ingham Swan Jersey/ Beaumont Channel Islands Mark Jordan at the Beach Kelvedon Essex George & Dragon Keyston Cambridgeshire Pheasant Kibworth Beauchamp Leicestershire Lighthouse London Brent Willesden Green Sushi-Say Bromley Pett’s Wood Indian Essence N Camden Bloomsbury -

E-Newsletter 6 June 2012 the COMPANY of the GREEN MAN

THE COMPANY OF THE GREEN MAN e-newsletter 6 June 2012 THE COMPANY OF THE GREEN MAN Greetings to all members of The Company of the Green Man! This is the sixth edition of The Company of the Green Man e- newsletter and I hope everyone finds something of interest amongst these pages. As in our last June edition Jack-in-the- Green takes precedence throughout these pages. But the Green Man as always will redress the balance in the December e- newsletter. I’m currently in the process of moving house and as we all know the third law of sod states “he who shall put his house on the market shall have a leaky flat roof on the same week” and so things were getting hectic and I began worrying that I might be late in getting this e-newsletter out to you all and miss my own June deadline. But then I glanced up at the bookshelf where my copies of Ron’s original newsletters for the Company of the Green Man sit and tried to remember when any of them ever actually arrived when he said they would. And so I realised that as the current caretaker of The Company of the Green Man it is actually my duty to carry on the tradition where possible of ensuring that the Company newsletter is in fact fashionably late. And so that was my excuse all ready to go. But then I sat down and began to look through the plethora of pictures and articles I had ready to go for this edition and the process flowed so smoothly and the pictures fitted together so effortlessly that I finished the e-newsletter earlier than ever before. -

125 March 1998

Hon. Secretary: Hon. Editor: VICE PRESIDENTS: Arthur Turner, Lionel Green and William Rudd BULLETIN NO. 125 MARCH 1998 PROGRAMME MARCH-JUNE Thursday 19th March 7.30 pm Merton Local Studies Centre, ‘Tramlink and its Historical Connections’ by John Gent of Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society Mr Gent is well-known as a transport specialist, a historian of Croydon, and the author of a number of books. (The Local Studies Centre is situated on the ground floor of Merton Civic Centre, London Road, Morden.) Friday 24th April 8pm The King’s Head, Merton High Street ‘The History of Young’s Brewery’ by Helen Osborn, archivist at Young’s and author of Inn and Around London, a history of Young’s pubs. (The King’s Head is opposite Savacentre, on bus routes 57, 152, 155, 200 and 293 and near Colliers Wood Underground station.) Saturday 16th May 2.30 for 3pm Guided tour of Southside House Cost: £5 (a concession rate of £3 is for members of the Historic Houses Association only) Behind a fine brick façade were until fairly recently two separate dwellings dating from (probably) the mid-18th century. Now, as a single house, Southside offers the visitor the chance to see an unusual interior and a collection around which myth and romance have accumulated. (Wimbledon Common Southside, buses 93, 200) Saturday 20th June Visit to Horsham, Sussex The visit will include the museum, the church, and a guided walk led by Marjorie Ledgerton, a long-time member of the Society and for a number of years our Bulletin editor. -

Country Dance Society of America (Annual National C.N.S., Buzzards Bay, Mass

The magazine of (a I end ar of Events THE COUNTRY DANCE SOCIETY OF AlillUCA June 23 - 26, 1961 DANCE WEEKEND at P:rnEHOOOO, Boston c.n.s. EDITOR Centre. THE May Gadd June 25 - 30 REX:CIIDER SESSIOO, John C. Campbell Folk School, Braastolll'l, N.c. ASSISTANT EDITORS counTR~ August 6 - 20 PINEliOOOO CAMP: 1.WO DANCE WEEKS, Hational A.C. King Diana Lockard Maxwell Reiskind C.D..S., Buzaarda B~, Mass. DAnCER CONTRIBUTING EDITORS August 8 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING, National C.D.S. Penn Elizabeth Schrader Evelyn K. Hells 7:15 p.m. at Pinewoods Camp, Buzzards Bay, J. Donnell Tilghman Roberta Yerkes Mass. ART EDITOR August 15 NATIONAL COUNCIL MEETING, National C.D.S. Genevieve Shimer 4:40 p.m. at Pinewood& Camp, Buzzards Bay, Mass. THE COUNTRY DANCER is published twice a year. Subscription is August 20 - 27 PINENOOOO CAMP: FOLK MUSIC AND REX:ORD.ER WEEK by membership in the Country Dance Society of America (annual National c.n.s., Buzzards Bay, Mass. dues $5, educational institutions and libraries $3.) Inquiries and subscriptions should be sent to the Secretary, Country Dance September 27 GET-TOOE"l'HER EVniilU, New York c.n.s. Society of America, 55 Christopher Street, New York 14, N.Y. September 28 NF)ol YORK REX:ORDER CLASS]S BID .Dr. Tel: ALgonquin 5-8895. Copyright 1961 by the Country Dance Society Inc. September 29 - ADULT SECTION MOUNTAIN FOLK FESTIVAL, Levi October 1 Jackson State Park, London, Ky. For infor mation wr1 te to: Miss Ethel Capps, Box 28'/, , Table of Contents Berea College, Berea, Ky. -

Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN Guide 2012

Great Britain & Ireland MICHELIN guide 2012 Bib Gourmands = N: New Bib Gourmands 2012 Town County Establishment England Aldeburgh Suffolk Lighthouse Alderley Edge Cheshire The Wizard Backwell Bristol New Inn Beaconsfield / Seer Green Buckinghamshire Jolly Cricketers Beverley East Riding of Yorkshire Whites Blackpool / Thornton Lancashire Twelve Bray Windsor & Maidenhead Hinds Head Brighton and Hove West Sussex Chilli Pickle Brighton and Hove / Hove West Sussex Ginger Pig Brighton and Hove / Hove West Sussex Meadow Bristol Bristol Flinty Red N Bristol Bristol Greens’ Dining Room Bruntingthorpe Leicestershire The Joiners N Bruton Somerset At The Chapel Burnham Market Norfolk Hoste Arms Bury Greater Manchester Waggon Bury St Edmunds Suffolk Pea Porridge Cambridge / Little Wilbraham Cambridgeshire Hole in the Wall Clitheroe/Wiswell Lancashire Freemasons Darlington / Hurworth-on-Tees Durham Bay Horse Droxford Hampshire Bakers Arms Durham Durham Bistro 21 East Chisenbury Wiltshire Red Lion Freehouse East Haddon Northamptonshire Red Lion N Exeter / Rockbeare Devon Jack in the Green Inn Guernsey / St Saviour Channel Islands Pavilion Hastings and St Leonards East Sussex St. Clements Henfield West Sussex The Ginger Fox Ingham Norfolk Ingham Swan N Itteringham Norfolk Walpole Arms Kelvedon Essex George and Dragon Knaresborough / Ferrensby North Yorkshire General Tarleton Inn Leeds West Yorkshire Piazza by Anthony Masham North Yorkshire Vennell’s Melton Mowbray / Stathern Leicestershire Red Lion Inn Millbrook / Freathy Cornwall View Norwich / Stoke -

Radical Deptford: a Place in Constant Motion

Deptford’s waterside location has played a crucial part in its development having been allowed, independently, to generate its own in London was one of the principal reasons that it was responses to its own predicaments. And yet the consistent chosen as the site of new or experimental construction. Radical Deptford: waves of innovation – from the naval to the horticultural, The Lenox, launched from Deptford in 1678 as the first of social work to municipal architectural, the educational to Pepys’ ‘Thirty Ships’, remained the backbone of the fleet the religious – that flow from this place are mostly linked for the rest of the century. to ideas people bring with them, and in turn Deptford’s Second only to Pepys as a diarist of the period was A Place in Constant Motion willingness to embrace and develop them. The sense of John Evelyn, who took up residence on the edge of the being ‘done to’ may have created significant social strain Royal Docks at Sayes Court Manor, the ancestral home of at times but equally this experimentation has contributed his wife. It was Evelyn, and later his descendent William, From Henry VIII’s Royal Docks to Michael Craig-Martin and considerably to the sense of Deptford as a place. who initiated a new phase of innovation on this site, his Research and innovation began in Deptford in 1513 with celebrated horticultural experiments with plants and Herzog de Meuron’s Laban building, Deptford embodies progress Henry VIII and the establishment of the Royal Docks. planting proving as hugely influential as his writing. -

Jack in the Green 2017

Jack In The Green and Other Heroes A collection of songs by Martin Graebe All song texts, music, notes and other matter are copyright © Martin Graebe (dates as given individually) unless otherwise stated in the notes to the songs. Published by Greenjack Publications, 59 Roberts Close, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 2RP Jack in the Green and other heroes A collection of songs by Martin Graebe A Sailor's Farewell Harry The Hawker A Hunting Song Harriet Lane Peter's Private Army Honiton Lace The Shropshire Union The Great Galleon of Plymouth Jack in the Green Newton Fair Eight Set's Song The Lavender Express From Severn, by the Somme November Drinking Song Stonecracker John Daniel's Ducks The Chorus Song The King of the Light-Finger Gentry The Knocker-up Woman The Singing Story Man Laying My Life on the Line The Road to Hell A few (more) words ………. In May 1978 I published a collection of my songs under the title 'The Singing Story Man'. That publication was a mix of hand-writing, drawings and Letraset - leading edge technology for the 70's. It sold steadily for many years and only a fragile few of that first collection are left. People asked me whether I was going to do it again and the answer was always ‘Someday!’ That day arrived in 1999. The technology was different but it was still my own work - with a lot of help from my family and friends. Some years ago I decided to make all my songs freely available on the internet and now, in 2017, I have re-created this book electronically for a revised and simplified version of the website. -

Quarterly Oftntamrwn Primrose Society

Quarterly oftntAmrwn Primrose Society VOLUME XXXIII FALL, 1975 NUMBER 4 American Primrose Society ) Quarterly OFFICERS President—Mr. Richard Charlton Rt. 4, Box 364, Gresham, Oregon 97030 of the Vice-Pres.—Mrs. Rosetta Jones 6214 South 287th St., Kent, Wash. 98031 Rec. Secry.—Mrs. William Dines 9017 180th Ave. N.E., Redmond, Wash. 98052 American Primrose Society Corres. Sec'y. East—Mrs. Alice Hills Baylor Stage Coach Rd., Rt 2. Stowe, Vt. 05672 Corres. Sec'y. West—Mr. Gus N. Arneson 1004 N.W. 179th PL, Seattle, 98177 NUMBER 4 Treasurer—Mrs. John Genheimer 7100 S.W. 209th, Beaverton, Oregon 97005 VOLUME XXXIII FALL, 1975 ELECTED DIRECTORS Miss Fayme Haverty, 72 Edmonds, Wn. Mr. Herbert Dicksoti, '73, Chehalis, Wash. Mrs. J. Genheimer, 72, Beaverton, Ore. Mrs. Alan Obersinner, '73, Silverton, Ore. Mrs. Wallace J. Balla '74 Greenwich, Conn. Mrs. Donald Bolton '74 Juneau, Alaska Mr Al Rapp, Immediate Past President ..4918 79th Ave. West, Tacoma, Wash. 98467 TABLE OF CONTENTS Mrs. Frank L. Springer, Editor, ex officio Presidents of affiliated Primrose Societies are included on the Board of Directors President's Message 4 QUARTERLY Florence Bellis — Editor Emeritus Down The Primrose Path 5 Editor—Mrs. Frank Springer 7213 South 15th St., Tacoma, Wn, 98465 The Elizabethan Primroses — Dorothy Springer 6 Regional Editors— Mrs. Donald Bolton P. 0. Box 187, Juneau, Alaska 99801 Your Primroses Need Fall Care 7 Mr. Elmer C. Baldwin 400 Techumseh Rd., Syacuse, N.Y. 13224 Lush Places — Norah Hart 8 Mrs. Alice Hills Baylor Stage Coach Road, Rt. 2, Stowe, Vermont 05672 Mrs. Grace M. Conboy 5846 S.E. -

AMN, October 1977, Vol. 1 No. 3

A ;:ullLic-ntiorl Editor: Fred Breunig devoted salehj to RFD # 1, Box 9A r.'rq l is h Morris and Sword Dancing. Putney, VT 0.5.34G VOL. I no. 3 October, 1977 "SUCCESS TO THE BOWER!" 2. .1..-:5 fl e . By J. M. Graetz 3. : , -I d 4 he City of Lichfield,:in Staffordshire, is fifteen miles north of Birnin4ham, or, £0; the more specifically beer-oriented, twelve miles southwest of ~urtonLon-Trent. With a population of.23, 00, it is about the ~ipeof..Amhergt, Mass. Aside from being the birfhplace of ~arnuec-Jobnson, Lich!ield is knoyn ,principally for its cathedral, which is the smallest in ~ngand, and the .oply one thgt atill has .all tbree spires.],: 1 - . , Sunday, 25 May 1975. I call David Burke, ~agman'bf' thebGtfen Man Morris and Sword Club, for directions to the Bower Festiqalg' ~&d: %oil t forg$t LO bring your bit I. ." 'I. I I ' Self : ''06,' .uh , ><ah, . I dan&riqg : it along. , David: "Wel'l, I 'assunit: yog're dancing w$t& us, ;of.aur?ei!' Self : "L--L' : (A g~~~$bG~,unexpected iwwfion does not leqd itself well I ' ta a pypgy comeback.) -r 4 . v .. 7 b i r The full .~%tEeob-.Mchf ield ' s Spring Festival is' "The Greenhill Boyer Ld our t :, of Array and View 3f $fen+&-Arms" '&id it has been inG'&sthce dearly as '-long. of A was originally &he annual in~~I1ch&fanlll&rf$qFtaonr hd k=4$es :$ according to Alex Helm [I], from the year '1285. , &re bedj- bt pr;sent 'go pped,., :- $or t$e City to maintain an independent military establishmdnt, "ti&' Court 'is -;ow held ";in a 'light- hearted way in the Guildhall, with leading .citfz'ehs b'&~' fined t$e stktutory: penm,,,pow.