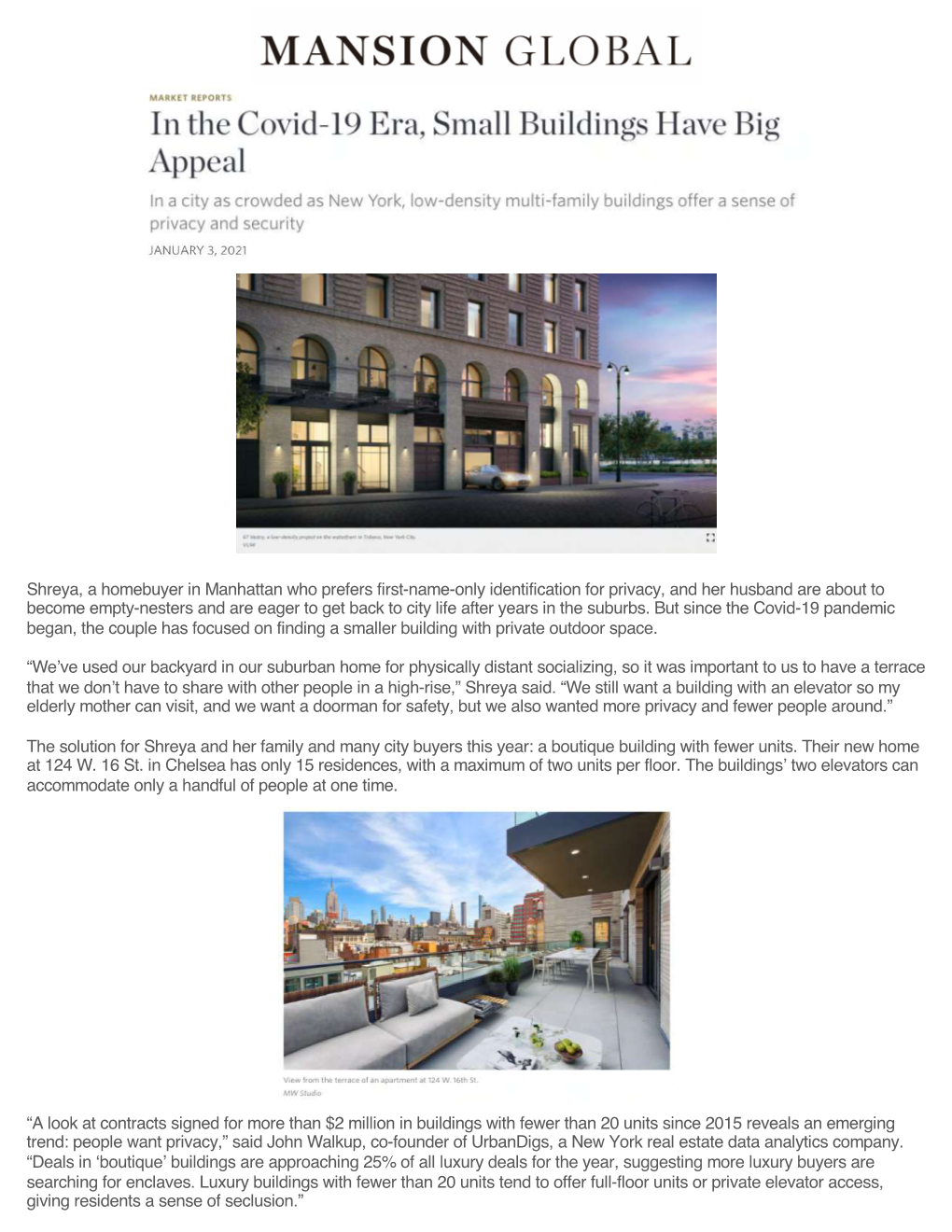

Shreya, a Homebuyer in Manhattan Who Prefers First-Name-Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N800458ZRM Amenaments of the Zoning Resolution

-44 " ar CITY PLANNING COMMISSION N800458ZRM February 9, 1981 / Calendar #1 to Section 200 of the New York Amenaments of the Zoning Resolution pursuant 15-00, and Charter relating to Article I, new Chapter 5, Section City conversion non-res- miscellaneous changes in other Sections, regarding the of Communitu Boards Z through 6. idential buildings to residential use in Manhattan S.- 0110". The amendments seek to protect the vitally important Manhattan based industries from the effects of unbridled conversion of loft buildings to residential use. Concurrently, additional opportunities are provided for housing in areas where residential use will not have an adverse impact on the City's economy. The zoning map changes define current manufacturing districts, create new mixed use districts, and remap a manufacturing district to commercial. The text changes establish standards for the conversion of non-residential buildings to residential use outside the manufacturing districts. The text changes also provide a mechanism for relocation assistance for industrial uses displaced by conversion when they relocate in New York City. BACKGROUND In adopting the 1961 zoning ordinance, the Board of Estimate-- sought to ensure "that sufficient space will be available for use for manufacturing and related activities". Large areas of Manhattan which were occupied by industrial uses were mapped manufacturing. Other areas with significant industrial activity were mapped commercial, because they were adjacent to the central business districts or residential areas. The industrial uses in these commercial areas were expected to decrease over time. The first major review of this policy was undertaken in 1963. In response to the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway, and to the sug- gestion that the area between Broome and Houston Streets be cleared for high-rise housing, Chester Rapkin was commissioned to study the S. -

Loft Conversions and the Building Regulations

A City and County of Swansea Dinas a Sir Abertawe Environment Department The Guildhall, Swansea SA1 4PE Tel No: (01792) 635636 Fax No: (01792) 648079 e-mail: www.swansea.gov.uk/bcon Minicom: (01792) 635609 LOFT CONVERSIONS and the BUILDING REGULATIONS Simplified Guidance LOCAL AUTHORITY BUILDING CONTROL SERVICES 2005 Rev1. C O N T E N T S Page 1:00 Introduction 3 2:00 Design Considerations 4 3:00 Structural Stability 5 4:00 Fire Safety 8 5:00 Ventilation 18 6:00 Staircase Access 21 7:00 Thermal Insulation 26 8:00 Electrical Safety 27 9:00 Typical Problems and Solutions 28 10:00 Checklist 32 The original edition of this document was developed by colleagues at Exeter City Council to whom Local Authority Building Control Wales are obliged Chapter 1:00 Introduction 1:10 This guidance booklet considers the extension of a typical 2 storey dwelling into a 3 storey unit, by the addition of a 'Loft Conversion' within the existing roof space. It is not possible, nor is it intended that this booklet should cover every aspect of the design. Primarily, it's purpose is to highlight the basic design considerations which need to be addressed. Specific technical detail has largely been omitted due to the criteria being subject to frequent change. If the proposal involves the conversion of a loft space above a bungalow, the fire safety provisions indicated in section 4:00 are not applicable, other than the arrangement of inner rooms. 1:20 For the purposes of this guidance, it is assumed the proposed conversion will not: (a) exceed 50 m2 in floor area, (b) involve raising the roof line above the existing ridge level, and (c) contain more that two habitable rooms, on the new second storey. -

Steps to Planning and Costing a Loft Conversion Uncovering Your Loft’S True Potential Can Be Tricky – Especially If All It Has Been So Far Is Rarely Visited Storage

LOFT CONVERSIONS Look at what you’ve got To ensure your space is worth converting, and to make it viable as a functioning and practical room, you ideally need the highest point to be at least 2.2m. There should be enough space to fit a new staircase – preferably within the existing landing area on the first floor – and a new landing into the loft rooom. Next, look at the roof. The gradient of its slope should be analysed, explains Sarah Livesey, director at Econoloft, as this will not only dictate the type of conversion possible, but also the finished layout. Generally speaking, the higher the pitch the taller the ceiling, and the more floor space you’ll have to work with. Anything above 30 degrees is workable. If you don’t have much head height, it’s still possible to convert – either by lowering the floor, raising the roof, or altering the shape of it by extending – but the project will cost more. To gain space, think about relocating a water tank if this is housed in the loft. Though 1you may need to install a new boiler or water system anyway if your existing plumbing can’t cope with serving additional rooms. If the loft has a chimneybreast, you may prefer to have it demolished if it will obstruct the layout. “Remember – this will impact the structural stability of the whole property, so it needs to be carefully managed with input from a structural engineer,” says Sarah. “Externally, check the condition of your roof tiles. If you need to re-tile or make repairs, do it as part of the conversion process.” 10STEPS TO PLANNING AND COSTING A LOFT CONVERSION Uncovering your loft’s true potential can be tricky – especially if all it has been so far is rarely visited storage. -

The Ultimate Guide to Creating a Loft Conversion with the Wow Factor Get Inspiration for Your Loft Conversion Contents

THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO CREATING A LOFT CONVERSION WITH THE WOW FACTOR GET INSPIRATION FOR YOUR LOFT CONVERSION CONTENTS A lof conversion can increase your property value by up to 20%. It can save you the headache, and heartache, of moving house to gain extra room. It can also be an excitng and stylish The Importance Of Good Design new space in your home, helping you to achieve the lifestyle Types Of Lof Conversion you’ve always dreamt of. Using Natural Light To Create Amazing Spaces Lof conversions do not have to be boring, practcal spaces; they can have the wow factor and become atractve, design- Lof Staircases led spaces for contemporary living. What kind of space do Heatng And Lightng Your Lof you want to create in your lof? A master bedroom with luxury ensuite, games room, home ofce or private retreat? Storage That Doesn’t Look Functonal Your lof conversion could be any of these, with the right space Inspiring Bathroom Design Ideas and some imaginaton. Smart Lofs And Smart Home Automaton This guide will take you through the many aspects of Eco Lofs: Reduce Your Carbon Footprint convertng your lof and help you decide what will work in your space and suit your needs. Our goal is to help you to Innovaton Is WOW! create a space you will love and be able to enjoy for years to come. We cover the following key factors that will shape your lof conversion - give them some thought now for a stress-free and successful conversion project: • The lof conversion experts you need on your team. -

Design Masterclass Loft Conversions

DESIGN DESIGN MASTERCLASS: Converting Loft Spaces GREAT IDEAS Experienced renovator and property developer Michael Holmes offers innovative design tips and practical advice sing the roof space to provide additional accommodation makes good sense. On a new dwelling it will maximise use of the built volume and bring down Uthe average cost per square metre. In an existing home, converting the loft is often the most cost-effective way to add space. There are two main options when it comes to design: to commission an architectural designer to produce drawings which can then be put out to builders on a competitive tender basis, or to hand the whole project over to a design and build contractor offering a one-stop service. Both will deal with planning permission, if required, and Building Regulations approval. Think 1 Ahead Designing a roof with future conversion in mind will allow for the expansion of living space should demand arise. Specifying either a cut roof or attic trusses instead of ‘fink’ trusses will add £1,500-2,000 to the average build cost but hugely simplify the conversion process. In addition, including a This self-contained loft apartment, designed plumbing and heating manifold in the roof by Brooke Fieldhouse Associates (01723 space, siting soil vent (SVP) pipes where they 871388), was created within a 1970s might be needed, and allowing space on bungalow, so the elderly owner’s adult son the consumer unit for power, lighting and could move back home to provide support. other circuits, will bring down the cost of The distinctive curved ceiling has been achieved with tongue-and-groove boards. -

Lofts Narrative

Joseph Pell Lombardi, Architect LOFTS Pioneering in the Urban Wilderness -- Title of a 1977 book by James Stratton INTRODUCTION “He adored New York City. He idolized it all out of proportion. Uh, no, make it he, he, romanticized it all out of proportion”. --The movie Manhattan by Woody Allen I have always sought out the older, forsaken buildings of New York City. In the 1940s and 1950s, as a child, I observed the then deteriorating residential areas of Harlem. In the 1960s, as a young architect, preservationist and investor, I became immersed in restoring multi-tenant rooming houses back to one family townhouses in the Upper West Side and the Kips Bay/Murray Hill areas of Manhattan. At the beginning of the 1970s, as I began to discover the fading magnifi cent commercial buildings of lower Manhattan, my focus shifted to converting warehouse and commercial buildings to residential use. At that time, lower Manhattan had hundreds of spectacular buildings which were physically and economically distressed. Like the townhouses of the 1960s, exploring lower Manhattan was the discovery of treasures; behind the beautiful, but dusty and poorly maintained, facades of lower Manhattan were magnifi cent lobbies, high ceilinged spaces with large windows, top fl oors with multiple skylights and, often, fully detailed interiors -- it was a preservation architect’s dream. At fi rst there was little competition in the residential conversion fi eld from other architects because it was an off -beat specialty consisting less of conventional architecture and more about preservation, retrofi tting, zoning obstacles and building code issues. It was also a waiting opportunity. -

Loft Conversions

Experts’ guide to Loft conversions brought to you by Lofts Unlock your home’s full potential with a loft conversion With house prices spiralling and competition for prime locations fierce, staying put and making the most of your home has never been a wiser decision Converting your loft space is one of the most This guide is designed to explain everything exciting and satisfying of all the home-improvement you need to know about planning, creating and projects. With up to 30% of your home’s floor enjoying the perfect loft conversion. From the space tied up in your loft, the scope for home suitability of your loft for conversion, to the types transformation and choosing what to do with of conversions available, different uses, planning all that new space above you is only limited by regulations, costings, step-by-step processes and your imagination. lots more – we hope this guide helps you on your way to transforming your home and creating the Why move to get more space when the alternative perfect new space. is staring you right in the face or, more accurately, looking down on you from on high? With such Quick guide – Click to go straight there a huge amount of potential in the house you’re Can your loft be converted? .....................................p3 already in (that, let’s face it, is often just used as Making the most of your new space ....................p4 a dumping ground for Christmas decorations, Six ways to convert your loft ....................................p6 camping gear and old toys), why go through the The importance of planning the staircase .........p15 stress of moving to a bigger place? Planning permission and regulations ..................p16 Party walls ......................................................................p18 So you’ve opened up your loft and gained How much will a new loft cost? ..............................p19 access to the space with a new staircase. -

Westbeth Other Names/Site Number Western Electric Company; Bell Telephone Laboratories; Bell Labs

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Westbeth other names/site number Western Electric Company; Bell Telephone Laboratories; Bell Labs 2. Location street & number 55 Bethune Street [ ] not for publication city or town New York [ ] vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10014 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements as set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [X] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [X] nationally [ ] statewide [ ] locally. -

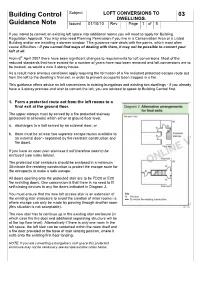

Loft Conversions to 03 Dwellings

Building Control Subject LOFT CONVERSIONS TO 03 DWELLINGS. Guidance Note Issued 01/01/13 Rev Page 1 of 5 If you intend to convert an existing loft space into additional rooms you will need to apply for Building Regulation Approval. You may also need Planning Permission if you live in a Conservation Area or a Listed Building and/or are installing a dormer window. This guidance note deals with the points, which most often cause difficulties - if you cannot find ways of dealing with them, it may not be possible to convert your loft at all. From 6th April 2007 there have been significant changes to requirements for loft conversions. Most of the reduced standards that have existed for a number of years have now been removed and loft conversions are to be treated, as would a new 3-storey house. As a result more onerous conditions apply requiring the formation of a fire resistant protected escape route out from the loft to the dwelling’s final exit, in order to prevent occupants been trapped in a fire. This guidance offers advice on loft conversions to existing bungalows and existing two dwellings - if you already have a 3-storey premise and wish to convert the loft, you are advised to speak to Building Control first. 1. Form a protected route out from the loft rooms to a final exit at the ground floor. The upper storeys must by served by a fire protected stairway (protected at all levels) which either at ground floor level: a. discharges to a hall served by an external door, or b. -

Guide to Extending Your Home 1

LOFT CONVERSIONS | GARAGE CONVERSIONS | CELLAR CONVERSIONS | DOMESTIC EXTENSIONS GUIDE TO your home Your expert guide to everything extending TNK Construction Ltd BUILDING YOU A BETTER HOME Building Your Dream Home A Perfectly Established Interior Avoid moving costs and the stresses that Once your new build or commercial come with upheaving your possessions by property is ready, it’s essential to make sure allowing us to expand the space you the interior is completed professionally. currently have. Whether it’s a loft conversion From dry lining and plastering to installing or an extension, we’ll also add value to doors, kitchens, and stairs, we have your property. it covered. Constructing New Build Bring Your Property Back Properties to Life Many first-time buyers often look at new Once you’re home starts to look old and tired, build homes due to their stylish appearance you may find yourself quickly falling out of and affordable costs. Taking on projects such love with your property. At TNK Construction as assembling a block of new flats or houses, Ltd, our builders are on hand to refurbish our team work tirelessly throughout. your house and breathe new life into it. T: 020 8128 9485 E: [email protected]. www.tnkltd.co.uk Toughened Glass Systems is one of the UK’s leading safety glass and glazing suppliers offering a range of products including: I ROOFLIGHTS I SKYLIGHTS I GLASS JULIET BALCONIES I GLASS PARTITIONS I GLASS BALUSTRADES I KITCHEN SPLASHBACKS I MIRRORS I STRUCTURAL WALK ON GLASS I SEALED DOUBLE GLAZED UNITS ....and many more products. -

Building Control Guidance Note

Building Control Subject LOFT CONVERSIONS TO 03 DWELLINGS. Guidance Note Issued 01/10/10 Rev Page 1 of 5 If you intend to convert an existing loft space into additional rooms you will need to apply for Building Regulation Approval. You may also need Planning Permission if you live in a Conservation Area or a Listed Building and/or are installing a dormer window. This guidance note deals with the points, which most often cause difficulties - if you cannot find ways of dealing with them, it may not be possible to convert your loft at all. From 6th April 2007 there have been significant changes to requirements for loft conversions. Most of the reduced standards that have existed for a number of years have now been removed and loft conversions are to be treated, as would a new 3-storey house. As a result more onerous conditions apply requiring the formation of a fire resistant protected escape route out from the loft to the dwelling’s final exit, in order to prevent occupants been trapped in a fire. This guidance offers advice on loft conversions to existing bungalows and existing two dwellings - if you already have a 3-storey premise and wish to convert the loft, you are advised to speak to Building Control first. 1. Form a protected route out from the loft rooms to a final exit at the ground floor. The upper storeys must by served by a fire protected stairway (protected at all levels) which either at ground floor level: a. discharges to a hall served by an external door, or b. -

Loft Conversions a Beginners Guide the Easy to Follow Guide to Extending Your Home Upwards

Home About Articles Loft Conversions A Beginners Guide The easy to follow guide to extending your home upwards Play Audio Article Printable PDF Show Article Contents Home About Articles Home > Articles > Loft Conversion Guide If you are looking for beginners guide to loft conversion, you've come to the right place. In this loft conversion guide, you're going to learn everything that you need to know about the following: Is a loft conversion possible for your property? Things to consider before you start Designs to consider for your loft conversion Potential costings All about planning permission Building regulations information Loft conversion design ideas How to begin with your loft conversion A loft conversion is an excellent way to expand your home; whether you need an extra bathroom, a guest suite or an additional study, a loft conversion is a fantastic way to provide your home with the space you want. Extending the space is often the best option over moving to a new property, too, and if you have space that is unused, building into it yourself could make that space functional. Show Article Index Whether you need an extra bathroom, a guest suite or an additional study, a loft conversion is a fantastic way to provide your home with the space you want Regardless of what you choose to turn your loft into, you will need to think deeply about so many things to do with your loft conversion; planning permission included. For every load you intend to build onto the existing floor, you need to ensure that it's capable of withstanding it.