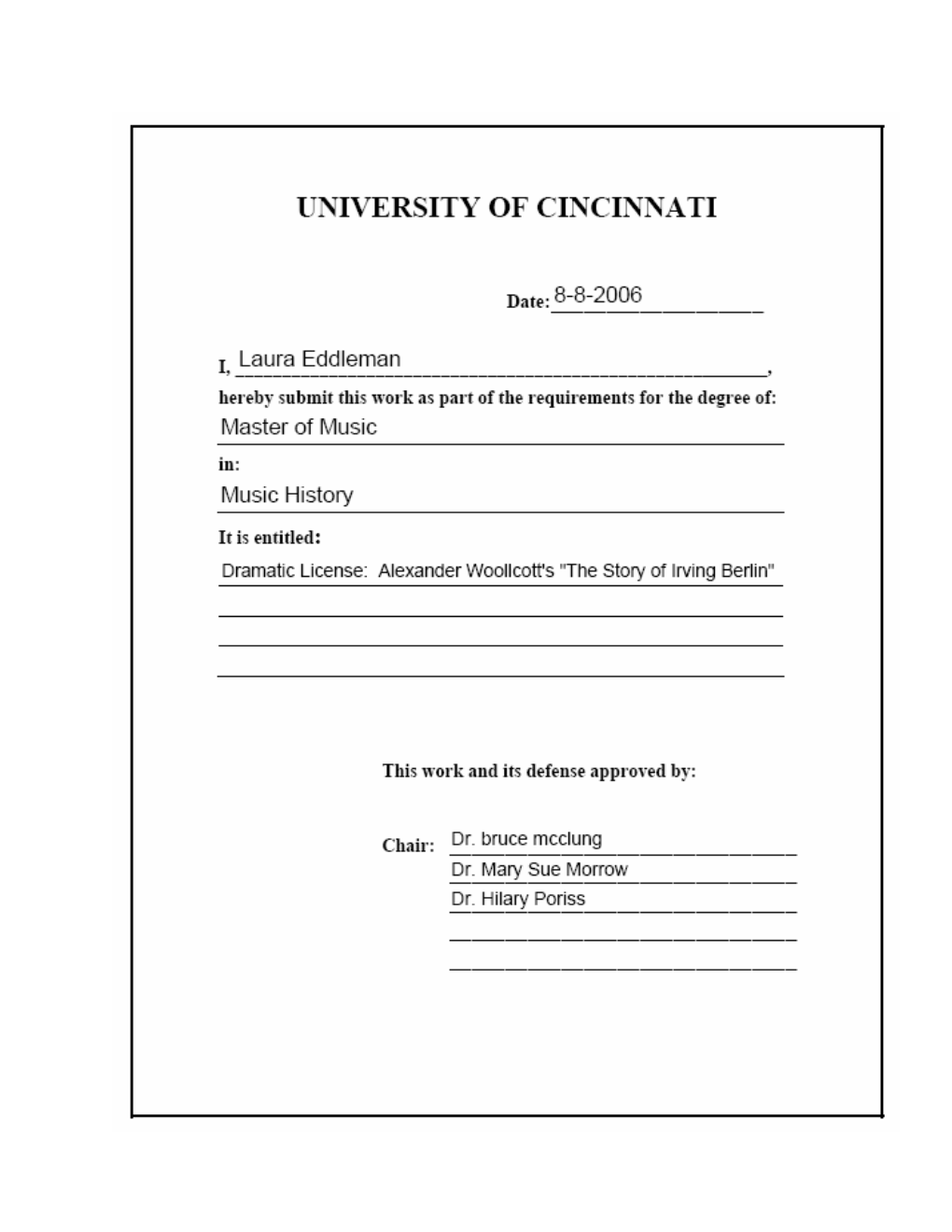

Alexander Woollcott's the Story of Irving Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jew Taboo: Jewish Difference and the Affirmative Action Debate

The Jew Taboo: Jewish Difference and the Affirmative Action Debate DEBORAH C. MALAMUD* One of the most important questions for a serious debate on affirmative action is why certain minority groups need affirmative action while others have succeeded without it. The question is rarely asked, however, because the comparisonthat most frequently comes to mind-i.e., blacks and Jews-is seen by many as taboo. Daniel A. Farberand Suzanna Sherry have breached that taboo in recent writings. ProfessorMalamud's Article draws on work in the Jewish Studies field to respond to Farberand Sherry. It begins by critiquing their claim that Jewish values account for Jewish success. It then explores and embraces alternative explanations-some of which Farberand Sheny reject as anti-Semitic-as essentialparts of the story ofJewish success in America. 1 Jews arepeople who are not what anti-Semitessay they are. Jean-Paul Sartre ha[s] written that for Jews authenticity means not to deny what in fact they are. Yes, but it also means not to claim more than one has a right to.2 Defenders of affirmative action today are publicly faced with questions once thought improper in polite company. For Jewish liberals, the most disturbing question on the list is that posed by the comparison between the twentieth-century Jewish and African-American experiences in the United States. It goes something like this: The Jews succeeded in America without affirmative action. In fact, the Jews have done better on any reasonable measure of economic and educational achievement than members of the dominant majority, and began to succeed even while they were still being discriminated against by this country's elite institutions. -

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

The Holocaust: Full Book List

Page 1 Holocaust Books for Young Readers Prejudice, Discrimination, Tolerance, Bullying, Being an Upstander The Sneetches by Dr. Seuss (1961) – Ages 4 - 8 Picture book that teaches children to be tolerant through a metaphor of what happened during the Holocaust https://greenvilleartspartnership.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/thesneetchesguide.p df https://www.teachingchildrenphilosophy.org/BookModule/TheSneetches Terrible Things: Allegory of the Holocaust by Eve Bunting (1996) Ages 6 and up. The author teaches children about the Holocaust through an allegory using animals. This introduction to the Holocaust encourages young children to stand up for what they think is right, without waiting for others to join them. It shows young readers the dangers of being silent in the face of danger. https://rapickering.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/terrible-things-questions.docx ______________________________________________________________ Brundibar by Toni Kushner (2003) – Ages 6 - 9 Picture book based on the Czech Opera performed by the children of Terezin. Brundibar tells the story of a brother and sister who stand up against tyranny with the help of other children in order to help their sick mother. http://www.ratiotheatre.org/Brund-SG www.pbs.org/now/arts/brundibar.html _____________________________________________________________ Star of Fear, Star of Hope by Jo Hoestlandt (1993) – Ages 7 - 10 The story of a nine year old girl who is confused by the disappearance of her Jewish friend during the Nazi occupation of Paris. www.holyfamilyregional.com/.../Star%20of%20Fear%20Star%20of%20Hope.p df _____________________________________________________________ Page 2 Mischling, Second Degree: My Childhood in Nazi Germany by Ilse Koehn (1977) Ages 11 - 14 A memoir of Ilse Koehn who is classified a Mischling, second degree citizen in Nazi Germany. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.36228 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Marie Ventura, “Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 02 March 2021, connection on 27 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/36228 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.36228 This text was automatically generated on 27 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx 1 Honks, Whistles, and Harp: The Transnational Sound of Harpo Marx Marie Ventura Introduction: a Transnational Trickster 1 In early autumn, 1933, New York critic Alexander Woollcott telephoned his friend Harpo Marx with a singular proposal. Having just learned that President Franklin Roosevelt was about to carry out his campaign promise to have the United States recognize the Soviet Union, Woollcott—a great friend and supporter of the Roosevelts, and Eleanor Roosevelt in particular—had decided “that Harpo Marx should be the first American artist to perform in Moscow after the US and the USSR become friendly nations” (Marx and Barber 297). “They’ll adore you,” Woollcott told him. “With a name like yours, how can you miss? Can’t you see the three-sheets? ‘Presenting Marx—In person’!” (Marx and Barber 297) 2 Harpo’s response, quite naturally, was a rather vehement: you’re crazy! The forty-four- year-old performer had no intention of going to Russia.1 In 1933, he was working in Hollywood as one of a family comedy team of four Marx Brothers: Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Zeppo. -

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in His Early Songs

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in his Early Songs A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Kimberly Gelbwasser B.M., Northwestern University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Mediterranean countries arrived in the United States. New York City, in particular, became a hub where various nationalities coexisted and intermingled. Adding to the immigrant population were massive waves of former slaves migrating from the South. In this radically multicultural environment, Irving Berlin, a Jewish- Russian immigrant, became a songwriter. The cultural interaction that had the most profound effect upon Berlin’s early songwriting from 1907 to 1914 was that between his own Jewish population and the African-American population in New York City. In his early songs, Berlin highlights both Jewish and African- American stereotypical identities. Examining stereotypical ethnic markers in Berlin’s early songs reveals how he first revised and then traded his old Jewish identity for a new American identity as the “King of Ragtime.” This document presents two case studies that explore how Berlin not only incorporated stereotypical musical and textual markers of “blackness” within two of his individual Jewish novelty songs, but also converted them later to genres termed “coon” and “ragtime,” which were associated with African Americans. -

Now and Forever — a Conversation with Israel Zangwill (New York: Robert M

Now and Forever — A Conversation with Israel Zangwill (New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1925), 156 pp. Another "by Jews, for Jews" special, from the Memory Hole. The tone of works such as this is quite different from what is presented in the media for general (i.e., "gentile") consumption. A strange little book I picked up. Samuel Roth discusses the state of Jewry with Israel Zangwill. Zangwill was a playwright who coined the phrase "melting pot" and who wrote a standard "refutation" of the Protocols . It deals with how Jews see themselves -- and how they think others see them. It's funny to see two Jews pretending to be "against" one another in a debate -- like two ants from the same anthill. All the extreme arrogance and subjectivity of Jews is displayed here. Jews are distinctive in the world in raising such things to near hallucinogenic levels. Compare with Hosmer and Marcus Eli Ravage. Some of the most incredible (or oddly candid) statements I highlighted in red as I went thru' the text. Jews say "we're special because we remember" -- their way of saying they institutionalize trans-generational ethnic hatred as a way of separating themselves from the rest of human society. My favorite part -- Roth compares St. Paul with Trotsky! He further says that Jews are the only real Christians, and that "Jesus preached of Jews and for Jews". He says that Jesus hated the world (when he really just hated Jews -- but Jews are "the world", according to them: all others are "not of Adam"). But we mustn't forget that this Problem is primarily an ethnic, and not a religious, one. -

Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth

Diaspora and Zionism in Jewish American Literature Brandeis Series in American Jewish History,Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor Leon A. Jick, The Americanization of the Synagogue, – Sylvia Barack Fishman, editor, Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction Gerald Tulchinsky, Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community Shalom Goldman, editor, Hebrew and the Bible in America: The First Two Centuries Marshall Sklare, Observing America’s Jews Reena Sigman Friedman, These Are Our Children: Jewish Orphanages in the United States, – Alan Silverstein, Alternatives to Assimilation: The Response of Reform Judaism to American Culture, – Jack Wertheimer, editor, The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed Sylvia Barack Fishman, A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community Diane Matza, editor, Sephardic-American Voices: Two Hundred Years of a Literary Legacy Joyce Antler, editor, Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture Jack Wertheimer, A People Divided: Judaism in Contemporary America Beth S. Wenger and Jeffrey Shandler, editors, Encounters with the “Holy Land”: Place, Past and Future in American Jewish Culture David Kaufman, Shul with a Pool: The “Synagogue-Center” in American Jewish History Roberta Rosenberg Farber and Chaim I. Waxman,editors, Jews in America: A Contemporary Reader Murray Friedman and Albert D. Chernin, editors, A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews Stephen J. Whitfield, In Search of American Jewish Culture Naomi W.Cohen, Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership Barbara Kessel, Suddenly Jewish: Jews Raised as Gentiles Jonathan N. Barron and Eric Murphy Selinger, editors, Jewish American Poetry: Poems, Commentary, and Reflections Steven T.Rosenthal, Irreconcilable Differences: The Waning of the American Jewish Love Affair with Israel Pamela S. -

The Great American Songbook in the Classical Voice Studio

THE GREAT AMERICAN SONGBOOK IN THE CLASSICAL VOICE STUDIO BY KATHERINE POLIT Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Patricia Wise, Research Director and Chair __________________________________ Gary Arvin __________________________________ Raymond Fellman __________________________________ Marietta Simpson ii For My Grandmothers, Patricia Phillips and Leah Polit iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the members of my committee—Professor Patricia Wise, Professor Gary Arvin, Professor Marietta Simpson and Professor Raymond Fellman—whose time and help on this project has been invaluable. I would like to especially thank Professor Wise for guiding me through my education at Indiana University. I am honored to have her as a teacher, mentor and friend. I am also grateful to Professor Arvin for helping me in variety of roles. He has been an exemplary vocal coach and mentor throughout my studies. I would like to give special thanks to Mary Ann Hart, who stepped in to help throughout my qualifying examinations, as well as Dr. Ayana Smith, who served as my minor field advisor. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their love and support throughout my many degrees. Your unwavering encouragement is the reason I have been -

"Ego, Scriptor Cantilenae": the Cantos and Ezra Pound

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 1991 "Ego, scriptor cantilenae": The Cantos and Ezra Pound Steven R. Gulick University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1991 Steven R. Gulick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Gulick, Steven R., ""Ego, scriptor cantilenae": The Cantos and Ezra Pound" (1991). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 753. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/753 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "EGO, SCRIPTOR CANTILENAE": THE CANTOS AND EZRA POUND An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Philosophy Steven R. Gulick University of Northern Iowa August 1991 ABSTRACT Can poetry "make new" the world? Ezra Pound thought so. In "Cantico del Sole" he said: "The thought of what America would be like/ If the Classics had a wide circulation/ Troubles me in my sleep" (Personae 183). He came to write an 815 page poem called The Cantos in which he presents "fragments" drawn from the literature and documents of the past in an attempt to build a new world, "a paradiso terreste" (The Cantos 802). This may be seen as either a noble gesture or sheer egotism. Pound once called The Cantos the "tale of the tribe" (Guide to Kulchur 194), and I believe this is so, particularly if one associates this statement with Allen Ginsberg's concerning The Cantos as a model of a mind, "like all our minds" (Ginsberg 14-16). -

Value Added: Jews in Postwar American Culture 69

Value Added: Jews in Postwar American completely secularized, even surpas. skepticism. So complete ~ triur Bless America" (1918, rev. 1938rcOl: Value Added: Jews in Postwar gled Banner" as the national antherr remember. The principle of separatiOi American Culture obstacle. 2 Until the early 1960s, however, th. pluralism were unrealized. Although Stephen J. Whitfield dency has not recurred, John F. Ker (BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY) longer necessary for the holder of the years later, another symbolic defeal conformity with the landmark U.S. Though Protestantism had long unoft the country, the Supreme Court bann five New York children challenged Americans are "descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, graders was eleven-year-old Joe Rotn professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very graduation, he later recalled, some of similar in their manners and customs," John Jay wrote in The Federalist No.2, in before talking to him.) The shock Wi defense of the new Constitution. 1 At least he got the politics right: All the basic Long Island and across the country. A political institutions of the United States had been created by the end of the eigh the Supreme Court's ruling, and lib· teenth century, and none since then. But the Framers could scarcely have imagined their outrage. Two years later, the Re how the culture would keep shifting into new configurations. Regional and ethnic whether 1964 was "the time for our I customs would vary widely, new languages would get injected (at least for one or our school rooms"; and a conservativ two generations) and religious pluralism would become legitimated, largely because increasing antisemitism if the Jews ~ Americans increasingly did not have the same ancestors.