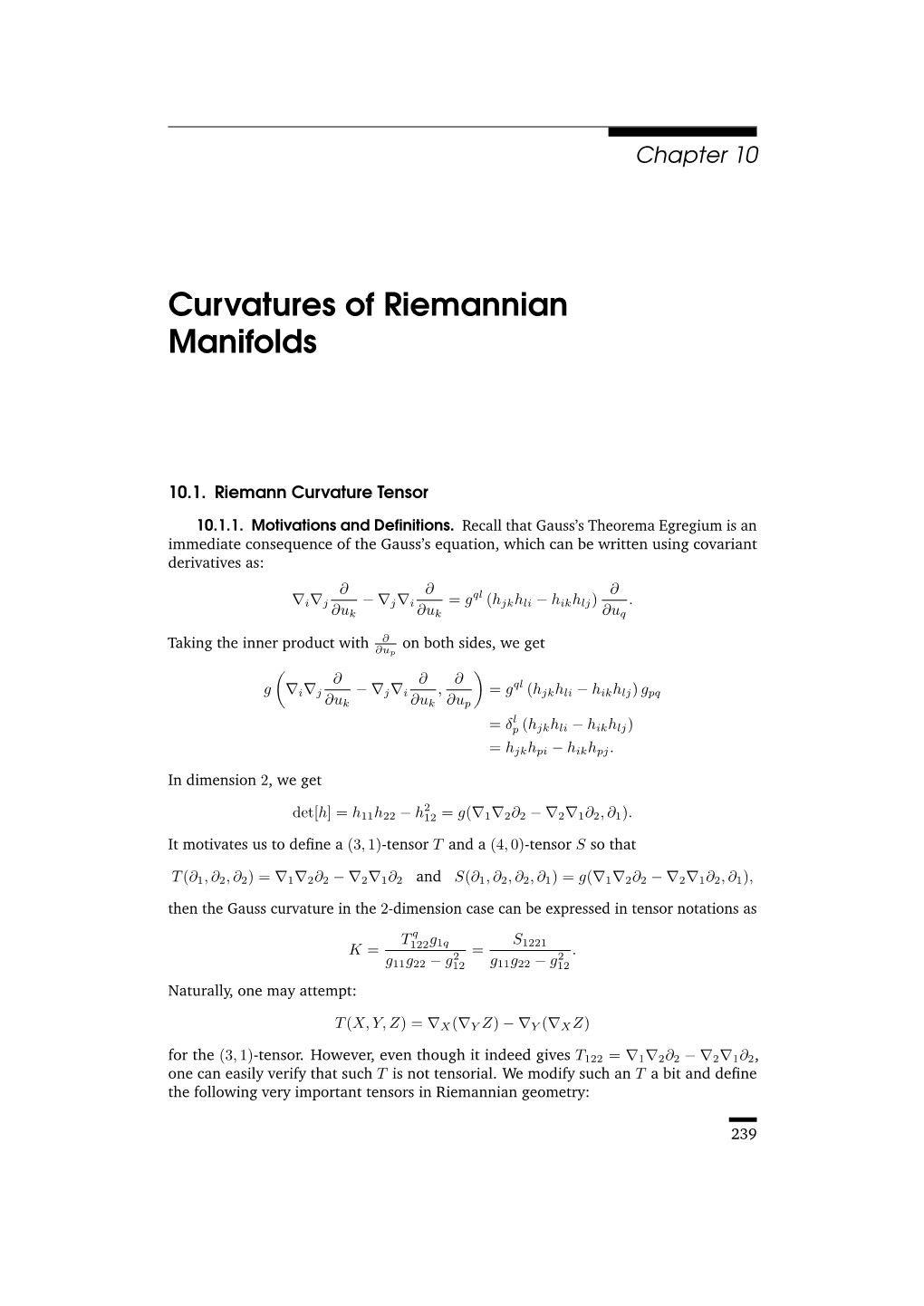

Curvatures of Riemannian Manifolds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grassmann Manifold

The Grassmann Manifold 1. For vector spaces V and W denote by L(V; W ) the vector space of linear maps from V to W . Thus L(Rk; Rn) may be identified with the space Rk£n of k £ n matrices. An injective linear map u : Rk ! V is called a k-frame in V . The set k n GFk;n = fu 2 L(R ; R ): rank(u) = kg of k-frames in Rn is called the Stiefel manifold. Note that the special case k = n is the general linear group: k k GLk = fa 2 L(R ; R ) : det(a) 6= 0g: The set of all k-dimensional (vector) subspaces ¸ ½ Rn is called the Grassmann n manifold of k-planes in R and denoted by GRk;n or sometimes GRk;n(R) or n GRk(R ). Let k ¼ : GFk;n ! GRk;n; ¼(u) = u(R ) denote the map which assigns to each k-frame u the subspace u(Rk) it spans. ¡1 For ¸ 2 GRk;n the fiber (preimage) ¼ (¸) consists of those k-frames which form a basis for the subspace ¸, i.e. for any u 2 ¼¡1(¸) we have ¡1 ¼ (¸) = fu ± a : a 2 GLkg: Hence we can (and will) view GRk;n as the orbit space of the group action GFk;n £ GLk ! GFk;n :(u; a) 7! u ± a: The exercises below will prove the following n£k Theorem 2. The Stiefel manifold GFk;n is an open subset of the set R of all n £ k matrices. There is a unique differentiable structure on the Grassmann manifold GRk;n such that the map ¼ is a submersion. -

Laplacians in Geometric Analysis

LAPLACIANS IN GEOMETRIC ANALYSIS Syafiq Johar syafi[email protected] Contents 1 Trace Laplacian 1 1.1 Connections on Vector Bundles . .1 1.2 Local and Explicit Expressions . .2 1.3 Second Covariant Derivative . .3 1.4 Curvatures on Vector Bundles . .4 1.5 Trace Laplacian . .5 2 Harmonic Functions 6 2.1 Gradient and Divergence Operators . .7 2.2 Laplace-Beltrami Operator . .7 2.3 Harmonic Functions . .8 2.4 Harmonic Maps . .8 3 Hodge Laplacian 9 3.1 Exterior Derivatives . .9 3.2 Hodge Duals . 10 3.3 Hodge Laplacian . 12 4 Hodge Decomposition 13 4.1 De Rham Cohomology . 13 4.2 Hodge Decomposition Theorem . 14 5 Weitzenb¨ock and B¨ochner Formulas 15 5.1 Weitzenb¨ock Formula . 15 5.1.1 0-forms . 15 5.1.2 k-forms . 15 5.2 B¨ochner Formula . 17 1 Trace Laplacian In this section, we are going to present a notion of Laplacian that is regularly used in differential geometry, namely the trace Laplacian (also called the rough Laplacian or connection Laplacian). We recall the definition of connection on vector bundles which allows us to take the directional derivative of vector bundles. 1.1 Connections on Vector Bundles Definition 1.1 (Connection). Let M be a differentiable manifold and E a vector bundle over M. A connection or covariant derivative at a point p 2 M is a map D : Γ(E) ! Γ(T ∗M ⊗ E) 1 with the properties for any V; W 2 TpM; σ; τ 2 Γ(E) and f 2 C (M), we have that DV σ 2 Ep with the following properties: 1. -

The Simplicial Ricci Tensor 2

The Simplicial Ricci Tensor Paul M. Alsing1, Jonathan R. McDonald 1,2 & Warner A. Miller3 1Information Directorate, Air Force Research Laboratory, Rome, New York 13441 2Insitut f¨ur Angewandte Mathematik, Friedrich-Schiller-Universit¨at-Jena, 07743 Jena, Germany 3Department of Physics, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The Ricci tensor (Ric) is fundamental to Einstein’s geometric theory of gravitation. The 3-dimensional Ric of a spacelike surface vanishes at the moment of time symmetry for vacuum spacetimes. The 4-dimensional Ric is the Einstein tensor for such spacetimes. More recently the Ric was used by Hamilton to define a non-linear, diffusive Ricci flow (RF) that was fundamental to Perelman’s proof of the Poincar`e conjecture. Analytic applications of RF can be found in many fields including general relativity and mathematics. Numerically it has been applied broadly to communication networks, medical physics, computer design and more. In this paper, we use Regge calculus (RC) to provide the first geometric discretization of the Ric. This result is fundamental for higher-dimensional generalizations of discrete RF. We construct this tensor on both the simplicial lattice and its dual and prove their equivalence. We show that the Ric is an edge-based weighted average of deficit divided by an edge-based weighted average of dual area – an expression similar to the vertex-based weighted average of the scalar curvature reported recently. We use this Ric in a third and independent geometric derivation of the RC Einstein tensor in arbitrary dimension. arXiv:1107.2458v1 [gr-qc] 13 Jul 2011 The Simplicial Ricci Tensor 2 1. -

Selected Papers on Teleparallelism Ii

SELECTED PAPERS ON TELEPARALLELISM Edited and translated by D. H. Delphenich Table of contents Page Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 1 1. The unification of gravitation and electromagnetism 1 2. The geometry of parallelizable manifold 7 3. The field equations 20 4. The topology of parallelizability 24 5. Teleparallelism and the Dirac equation 28 6. Singular teleparallelism 29 References ……………………………………………………………………….. 33 Translations and time line 1928: A. Einstein, “Riemannian geometry, while maintaining the notion of teleparallelism ,” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 17 (1928), 217- 221………………………………………………………………………………. 35 (Received on June 7) A. Einstein, “A new possibility for a unified field theory of gravitation and electromagnetism” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 17 (1928), 224-227………… 42 (Received on June 14) R. Weitzenböck, “Differential invariants in EINSTEIN’s theory of teleparallelism,” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 17 (1928), 466-474……………… 46 (Received on Oct 18) 1929: E. Bortolotti , “ Stars of congruences and absolute parallelism: Geometric basis for a recent theory of Einstein ,” Rend. Reale Acc. dei Lincei 9 (1929), 530- 538...…………………………………………………………………………….. 56 R. Zaycoff, “On the foundations of a new field theory of A. Einstein,” Zeit. Phys. 53 (1929), 719-728…………………………………………………............ 64 (Received on January 13) Hans Reichenbach, “On the classification of the new Einstein Ansatz on gravitation and electricity,” Zeit. Phys. 53 (1929), 683-689…………………….. 76 (Received on January 22) Selected papers on teleparallelism ii A. Einstein, “On unified field theory,” Sitzber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 18 (1929), 2-7……………………………………………………………………………….. 82 (Received on Jan 30) R. Zaycoff, “On the foundations of a new field theory of A. Einstein; (Second part),” Zeit. Phys. 54 (1929), 590-593…………………………………………… 89 (Received on March 4) R. -

Riemannian Geometry and the General Theory of Relativity

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Riemannian geometry and the general theory of relativity Marie McBride Vanisko The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Vanisko, Marie McBride, "Riemannian geometry and the general theory of relativity" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8075. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8075 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. p m TH3 OmERAl THEORY OF RELATIVITY By Marie McBride Vanisko B.A., Carroll College, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MOKT/JTA 1967 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners D e a ^ Graduante school V AUG 8 1967, Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. V W Number: EP38876 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduotion is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missir^ pages, these will be noted. Also, if matedal had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oi*MMtion neiitNna UMi EP38876 Published ProQuest LLQ (2013). -

2. Chern Connections and Chern Curvatures1

1 2. Chern connections and Chern curvatures1 Let V be a complex vector space with dimC V = n. A hermitian metric h on V is h : V £ V ¡¡! C such that h(av; bu) = abh(v; u) h(a1v1 + a2v2; u) = a1h(v1; u) + a2h(v2; u) h(v; u) = h(u; v) h(u; u) > 0; u 6= 0 where v; v1; v2; u 2 V and a; b; a1; a2 2 C. If we ¯x a basis feig of V , and set hij = h(ei; ej) then ¤ ¤ ¤ ¤ h = hijei ej 2 V V ¤ ¤ ¤ ¤ where ei 2 V is the dual of ei and ei 2 V is the conjugate dual of ei, i.e. X ¤ ei ( ajej) = ai It is obvious that (hij) is a hermitian positive matrix. De¯nition 0.1. A complex vector bundle E is said to be hermitian if there is a positive de¯nite hermitian tensor h on E. r Let ' : EjU ¡¡! U £ C be a trivilization and e = (e1; ¢ ¢ ¢ ; er) be the corresponding frame. The r hermitian metric h is represented by a positive hermitian matrix (hij) 2 ¡(; EndC ) such that hei(x); ej(x)i = hij(x); x 2 U Then hermitian metric on the chart (U; ') could be written as X ¤ ¤ h = hijei ej For example, there are two charts (U; ') and (V; Ã). We set g = à ± '¡1 :(U \ V ) £ Cr ¡¡! (U \ V ) £ Cr and g is represented by matrix (gij). On U \ V , we have X X X ¡1 ¡1 ¡1 ¡1 ¡1 ei(x) = ' (x; "i) = à ± à ± ' (x; "i) = à (x; gij"j) = gijà (x; "j) = gije~j(x) j j For the metric X ~ hij = hei(x); ej(x)i = hgike~k(x); gjle~l(x)i = gikhklgjl k;l that is h = g ¢ h~ ¢ g¤ 12008.04.30 If there are some errors, please contact to: [email protected] 2 Example 0.2 (Fubini-Study metric on holomorphic tangent bundle T 1;0Pn). -

“Geodesic Principle” in General Relativity∗

A Remark About the “Geodesic Principle” in General Relativity∗ Version 3.0 David B. Malament Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science 3151 Social Science Plaza University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA 92697-5100 [email protected] 1 Introduction General relativity incorporates a number of basic principles that correlate space- time structure with physical objects and processes. Among them is the Geodesic Principle: Free massive point particles traverse timelike geodesics. One can think of it as a relativistic version of Newton’s first law of motion. It is often claimed that the geodesic principle can be recovered as a theorem in general relativity. Indeed, it is claimed that it is a consequence of Einstein’s ∗I am grateful to Robert Geroch for giving me the basic idea for the counterexample (proposition 3.2) that is the principal point of interest in this note. Thanks also to Harvey Brown, Erik Curiel, John Earman, David Garfinkle, John Manchak, Wayne Myrvold, John Norton, and Jim Weatherall for comments on an earlier draft. 1 ab equation (or of the conservation principle ∇aT = 0 that is, itself, a conse- quence of that equation). These claims are certainly correct, but it may be worth drawing attention to one small qualification. Though the geodesic prin- ciple can be recovered as theorem in general relativity, it is not a consequence of Einstein’s equation (or the conservation principle) alone. Other assumptions are needed to drive the theorems in question. One needs to put more in if one is to get the geodesic principle out. My goal in this short note is to make this claim precise (i.e., that other assumptions are needed). -

Riemannian Geometry Learning for Disease Progression Modelling Maxime Louis, Raphäel Couronné, Igor Koval, Benjamin Charlier, Stanley Durrleman

Riemannian geometry learning for disease progression modelling Maxime Louis, Raphäel Couronné, Igor Koval, Benjamin Charlier, Stanley Durrleman To cite this version: Maxime Louis, Raphäel Couronné, Igor Koval, Benjamin Charlier, Stanley Durrleman. Riemannian geometry learning for disease progression modelling. 2019. hal-02079820v2 HAL Id: hal-02079820 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02079820v2 Preprint submitted on 17 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Riemannian geometry learning for disease progression modelling Maxime Louis1;2, Rapha¨elCouronn´e1;2, Igor Koval1;2, Benjamin Charlier1;3, and Stanley Durrleman1;2 1 Sorbonne Universit´es,UPMC Univ Paris 06, Inserm, CNRS, Institut du cerveau et de la moelle (ICM) 2 Inria Paris, Aramis project-team, 75013, Paris, France 3 Institut Montpelli`erainAlexander Grothendieck, CNRS, Univ. Montpellier Abstract. The analysis of longitudinal trajectories is a longstanding problem in medical imaging which is often tackled in the context of Riemannian geometry: the set of observations is assumed to lie on an a priori known Riemannian manifold. When dealing with high-dimensional or complex data, it is in general not possible to design a Riemannian geometry of relevance. In this paper, we perform Riemannian manifold learning in association with the statistical task of longitudinal trajectory analysis. -

On Manifolds of Tensors of Fixed Tt-Rank

ON MANIFOLDS OF TENSORS OF FIXED TT-RANK SEBASTIAN HOLTZ, THORSTEN ROHWEDDER, AND REINHOLD SCHNEIDER Abstract. Recently, the format of TT tensors [19, 38, 34, 39] has turned out to be a promising new format for the approximation of solutions of high dimensional problems. In this paper, we prove some new results for the TT representation of a tensor U ∈ Rn1×...×nd and for the manifold of tensors of TT-rank r. As a first result, we prove that the TT (or compression) ranks ri of a tensor U are unique and equal to the respective seperation ranks of U if the components of the TT decomposition are required to fulfil a certain maximal rank condition. We then show that d the set T of TT tensors of fixed rank r forms an embedded manifold in Rn , therefore preserving the essential theoretical properties of the Tucker format, but often showing an improved scaling behaviour. Extending a similar approach for matrices [7], we introduce certain gauge conditions to obtain a unique representation of the tangent space TU T of T and deduce a local parametrization of the TT manifold. The parametrisation of TU T is often crucial for an algorithmic treatment of high-dimensional time-dependent PDEs and minimisation problems [33]. We conclude with remarks on those applications and present some numerical examples. 1. Introduction The treatment of high-dimensional problems, typically of problems involving quantities from Rd for larger dimensions d, is still a challenging task for numerical approxima- tion. This is owed to the principal problem that classical approaches for their treatment normally scale exponentially in the dimension d in both needed storage and computa- tional time and thus quickly become computationally infeasable for sensible discretiza- tions of problems of interest. -

Geodesic Spheres in Grassmann Manifolds

GEODESIC SPHERES IN GRASSMANN MANIFOLDS BY JOSEPH A. WOLF 1. Introduction Let G,(F) denote the Grassmann manifold consisting of all n-dimensional subspaces of a left /c-dimensional hermitian vectorspce F, where F is the real number field, the complex number field, or the algebra of real quater- nions. We view Cn, (1') tS t Riemnnian symmetric space in the usual way, and study the connected totally geodesic submanifolds B in which any two distinct elements have zero intersection as subspaces of F*. Our main result (Theorem 4 in 8) states that the submanifold B is a compact Riemannian symmetric spce of rank one, and gives the conditions under which it is a sphere. The rest of the paper is devoted to the classification (up to a global isometry of G,(F)) of those submanifolds B which ure isometric to spheres (Theorem 8 in 13). If B is not a sphere, then it is a real, complex, or quater- nionic projective space, or the Cyley projective plane; these submanifolds will be studied in a later paper [11]. The key to this study is the observation thut ny two elements of B, viewed as subspaces of F, are at a constant angle (isoclinic in the sense of Y.-C. Wong [12]). Chapter I is concerned with sets of pairwise isoclinic n-dimen- sional subspces of F, and we are able to extend Wong's structure theorem for such sets [12, Theorem 3.2, p. 25] to the complex numbers nd the qua- ternions, giving a unified and basis-free treatment (Theorem 1 in 4). -

Math 865, Topics in Riemannian Geometry

Math 865, Topics in Riemannian Geometry Jeff A. Viaclovsky Fall 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Lecture 1: September 4, 2007 4 2.1 Metrics, vectors, and one-forms . 4 2.2 The musical isomorphisms . 4 2.3 Inner product on tensor bundles . 5 2.4 Connections on vector bundles . 6 2.5 Covariant derivatives of tensor fields . 7 2.6 Gradient and Hessian . 9 3 Lecture 2: September 6, 2007 9 3.1 Curvature in vector bundles . 9 3.2 Curvature in the tangent bundle . 10 3.3 Sectional curvature, Ricci tensor, and scalar curvature . 13 4 Lecture 3: September 11, 2007 14 4.1 Differential Bianchi Identity . 14 4.2 Algebraic study of the curvature tensor . 15 5 Lecture 4: September 13, 2007 19 5.1 Orthogonal decomposition of the curvature tensor . 19 5.2 The curvature operator . 20 5.3 Curvature in dimension three . 21 6 Lecture 5: September 18, 2007 22 6.1 Covariant derivatives redux . 22 6.2 Commuting covariant derivatives . 24 6.3 Rough Laplacian and gradient . 25 7 Lecture 6: September 20, 2007 26 7.1 Commuting Laplacian and Hessian . 26 7.2 An application to PDE . 28 1 8 Lecture 7: Tuesday, September 25. 29 8.1 Integration and adjoints . 29 9 Lecture 8: September 23, 2007 34 9.1 Bochner and Weitzenb¨ock formulas . 34 10 Lecture 9: October 2, 2007 38 10.1 Manifolds with positive curvature operator . 38 11 Lecture 10: October 4, 2007 41 11.1 Killing vector fields . 41 11.2 Isometries . 44 12 Lecture 11: October 9, 2007 45 12.1 Linearization of Ricci tensor . -

A Geodesic Connection in Fréchet Geometry

A geodesic connection in Fr´echet Geometry Ali Suri Abstract. In this paper first we propose a formula to lift a connection on M to its higher order tangent bundles T rM, r 2 N. More precisely, for a given connection r on T rM, r 2 N [ f0g, we construct the connection rc on T r+1M. Setting rci = rci−1 c, we show that rc1 = lim rci exists − and it is a connection on the Fr´echet manifold T 1M = lim T iM and the − geodesics with respect to rc1 exist. In the next step, we will consider a Riemannian manifold (M; g) with its Levi-Civita connection r. Under suitable conditions this procedure i gives a sequence of Riemannian manifolds f(T M, gi)gi2N equipped with ci c1 a sequence of Riemannian connections fr gi2N. Then we show that r produces the curves which are the (local) length minimizer of T 1M. M.S.C. 2010: 58A05, 58B20. Key words: Complete lift; spray; geodesic; Fr´echet manifolds; Banach manifold; connection. 1 Introduction In the first section we remind the bijective correspondence between linear connections and homogeneous sprays. Then using the results of [6] for complete lift of sprays, we propose a formula to lift a connection on M to its higher order tangent bundles T rM, r 2 N. More precisely, for a given connection r on T rM, r 2 N [ f0g, we construct its associated spray S and then we lift it to a homogeneous spray Sc on T r+1M [6]. Then, using the bijective correspondence between connections and sprays, we derive the connection rc on T r+1M from Sc.