California Property Tax an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TANGIBLE PROPERTY TAX RETURN (REVENUE FORMS 62A500, 62A500-A, 62A500-C, 62A500-L and 62A500-W)

INSTRUCTIONS TANGIBLE PROPERTY TAX RETURN (REVENUE FORMS 62A500, 62A500-A, 62A500-C, 62A500-L and 62A500-W) Classification of Property—Real property includes all lands within Definitions and General Instructions this state and improvements thereon. Intangible property consists of any property or investment that represents evidence of value or The tangible personal property tax return includes instructions to the right to value under law or customs. Tangible personal property assist taxpayers in preparing Revenue Forms 62A500, 62A500-A is every physical item subject to ownership, except real and intan- and 62A500-W. These instructions do not supersede the Kentucky gible property. Constitution or applicable Kentucky Revised Statutes. Depreciable Assets—List depreciable assets on the appropriate Taxpayer—All individuals and business entities who own, lease schedule(s) at original cost. Apply appropriate factor(s) to obtain or have a beneficial interest in taxable tangible property located reported value. Do not use book depreciation for computing the within Kentucky on January 1 must file a tangible property tax fair cash value of depreciable assets. Do not include noncommer- return. All tangible property is taxable, except the following: cial aircraft, documented boats, non-Kentucky registered watercraft and assets used in farming. See line-by-line instructions for details. personal household goods used in the home; crops grown in the year which the assessment is made and in the Lessors and Lessees of Tangible Personal Property—Leased hands of the producer; property must be listed by the owner on Revenue Form 62A500, tangible personal property owned by institutions exempted under regardless of the lease agreement’s terms regarding tax liability. -

Tax Appeals Rules Procedures

Tax Appeals Tribunal Rules & Procedures The rules of the game February 2017 Glossary of terms KRA Kenya Revenue Authority TAT Tax Appeals Tribunal TATA Tax Appeals Tribunal Act TPA Tax Procedures Act VAT Value Added Tax 2 © Deloitte & Touche 2017 Definition of terms Tax decision means: a) An assessment; Tax law means: b) A determination of tax payable made to a a) The Tax Procedures Act; trustee-in-bankruptcy, receiver, or b) The Income Tax Act, Value Added liquidator; Tax Act, and Excise Duty Act; and c) A determination of the amount that a tax c) Any Regulations or other subsidiary representative, appointed person, legislation made under the Tax director or controlling member is liable Procedures Act or the Income Tax for under specified sections in the TPA; Act, Value Added Tax Act, and Excise d) A decision on an application by a Duty Act. taxpayer to amend their self-assessment return; Objection decision means: e) A refund decision; f) A decision requiring repayment of a The Commissioner’s decision either to refund; or allow an objection in whole or in part, or g) A demand for a penalty. disallow it. Appealable decision means: a) An objection decision; and b) Any other decision made under a tax law but excludes– • A tax decision; or • A decision made in the course of making a tax decision. 3 © Deloitte & Touche 2017 Pre-objection process; management of KRA Audit KRA Audit Notes The TPA allows the Commissioner to issue to • The KRA Audits are a tax payer a default assessment, amended undertaken by different assessment or an advance assessment departments of the KRA that (Section 29 to 31 TPA). -

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

What Is So Special About Intangible Property? the Case for Intelligent Carryovers Richard A

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2010 What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The Case for intelligent Carryovers Richard A. Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Epstein, "What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The asC e for intelligent Carryovers" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 524, 2010). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 524 (2D SERIES) What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The Case for Intelligent Carryovers Richard A. Epstein THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2010 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. WHAT IS SO SPECIAL ABOUT INTANGIBLE PROPERTY? THE CASE FOR INTELLIGENT CARRYOVERS by Richard A. Epstein* ABSTRACT One of the major controversies in modern intellectual property law is the extent to which property rights conceptions, developed in connection with land or other forms of tangible property, can be carried over to different forms of property, such as rights in the spectrum or in patents and copyrights. -

An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M

TaxingTaxing Simply Simply District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission TaxingTaxing FairlyFairly Full Report District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 550 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 518-7275 Fax: (202) 466-7967 www.dctrc.org The Authors Robert M. Schwab Professor, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Amy Rehder Harris Graduate Assistant, Department of Economics University of Maryland College Park, Md. Authors’ Acknowledgments We thank Kim Coleman for providing us with the assessment data discussed in the section “The Incidence of a Graded Property Tax in the District of Columbia.” We also thank Joan Youngman and Rick Rybeck for their help with this project. CHAPTER G An Analysis of the Graded Property Tax Robert M. Schwab and Amy Rehder Harris Introduction In most jurisdictions, land and improvements are taxed at the same rate. The District of Columbia is no exception to this general rule. Consider two homes in the District, each valued at $100,000. Home A is a modest home on a large lot; suppose the land and structures are each worth $50,000. Home B is a more sub- stantial home on a smaller lot; in this case, suppose the land is valued at $20,000 and the improvements at $80,000. Under current District law, both homes would be taxed at a rate of 0.96 percent on the total value and thus, as Figure 1 shows, the owners of both homes would face property taxes of $960.1 But property can be taxed in many ways. Under a graded, or split-rate, tax, land is taxed more heavily than structures. -

Imagereal Capture

Some Aspects of Theft of Computer Software by M. Dunning I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to test the capability of New Zealand law to adequately deal with the impact that computers have on current notions of crimes relating to property. Has the criminal law kept pace with technology and continued to protect property interests or is our law flexible enough to be applied to new situations anyway? The increase of the moneyless society may mean a decrease in money motivated crimes of violence such as robbery, and an increase in white collar crime. Every aspect of life is being computerised-even our per sonality is on character files, with the attendant )ossibility of criminal breach of privacy. The problems confronted in this area are mostly definitional. While it may be easy to recognise morally opprobrious conduct, the object of such conduct may not be so easily categorised as criminal. A factor of this is a general lack of understanding of the computer process, so this would seem an appropriate place to begin the inquiry. II. THE COMPUTER Whiteside I identifies five key elements in a computer system. (1) Translation of data into a form readable by the computer, called input; and subject to manipulation by the introduction of false data. Remote terminals can be situated anywhere outside the cen tral processing unit (CPU), connected by (usually) telephone wires over which data may be transmitted, e.g. New Zealand banks on line to Databank. Outside users are given a site code number (identifying them) and an access code number (enabling entry to the CPU) which "plug" their remote terminal in. -

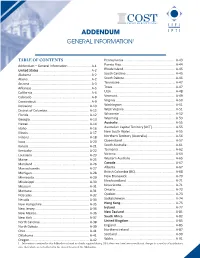

Addendum General Information1

ADDENDUM GENERAL INFORMATION1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pennsylvania ......................................................... A-43 Addendum – General Information ......................... A-1 Puerto Rico ........................................................... A-44 United States ......................................................... A-2 Rhode Island ......................................................... A-45 Alabama ................................................................. A-2 South Carolina ...................................................... A-45 Alaska ..................................................................... A-2 South Dakota ........................................................ A-46 Arizona ................................................................... A-3 Tennessee ............................................................. A-47 Arkansas ................................................................. A-5 Texas ..................................................................... A-47 California ................................................................ A-6 Utah ...................................................................... A-48 Colorado ................................................................. A-8 Vermont................................................................ A-49 Connecticut ............................................................ A-9 Virginia ................................................................. A-50 Delaware ............................................................. -

A Sui Generis Regime for Traditional Knowledge: the Ulturc Al Divide in Intellectual Property Law J

Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 3 Emerging Scholars Series: A Sui Generis Regime for Traditional Knowledge: The ulturC al Divide in Intellectual Property Law J. Janewa OseiTutu University of Pittsburgh School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/iplr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons Repository Citation J. Janewa OseiTutu, Emerging Scholars Series: A Sui Generis Regime for Traditional Knowledge: The Cultural Divide in Intellectual Property Law, 15 Intellectual Property L. Rev. 147 (2011). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/iplr/vol15/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Intellectual Property Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMERGING SCHOLARS SERIES* A SUI GENERIS REGIME FOR TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE: THE CULTURAL DIVIDE IN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW J. JANEWA OSEITUTU** ABSTRACT .................................................................................................... 149 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 150 I. THE TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE QUESTION ..................................... 158 A. The Backlash against TRIPS ...................................................... 158 B. What Is Traditional Knowledge? ............................................... -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

Intangible Takings Susan Eisenberg

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 60 | Issue 2 Article 13 3-2007 Intangible Takings Susan Eisenberg Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Susan Eisenberg, Intangible Takings, 60 Vanderbilt Law Review 667 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol60/iss2/13 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES Intangible Takings INTRODU CTION .................................................................... 668 II. THE LEGAL CONTEXT OF INTANGIBLE TAKINGS .................. 673 A. ConstitutionalProtection of Private Property......... 673 1. Defining Property in the Takings Clause .... 674 2. Absence of Qualifying Test for Intangible Property Interests ........................................ 676 B. TraditionalLaw Affords No Property Interest in Phone N um bers ................................................... 676 1. FCC Rules Governing Ownership of Phone N um bers ....................................................... 676 2. Contract Law ................................................ 678 3. Intellectual Property Law ............................ 679 C. Denial of Protective Rights Produces Incongruous Law .................................................... -

![[PDF] Intangible Property Section of Uniform Administrative](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3841/pdf-intangible-property-section-of-uniform-administrative-253841.webp)

[PDF] Intangible Property Section of Uniform Administrative

§ 3019.35 7 CFR Ch. XXX (1–1–06 Edition) the equipment shall be subject to the (2) Authorize others to receive, repro- provisions for federally-owned equip- duce, publish, or otherwise use such ment. data for Federal purposes. (d) (1) In addition, in response to a § 3019.35 Supplies and other expend- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) re- able property. quest for research data relating to pub- (a) Title to supplies and other ex- lished research findings produced under pendable property shall vest in the re- an award that were used by the Federal cipient upon acquisition. If there is a Government in developing an agency residual inventory of unused supplies action that has the force and effect of exceeding $5000 in total aggregate law, the Federal awarding agency shall value upon termination or completion request, and the recipient shall pro- of the project or program and the sup- vide, within a reasonable time, the re- plies are not needed for any other fed- search data so that they can be made erally-sponsored project or program, available to the public through the pro- the recipient shall retain the supplies cedures established under the FOIA. If for use on non-Federal sponsored ac- the Federal awarding agency obtains tivities or sell them, but shall, in ei- the research data solely in response to ther case, compensate the Federal Gov- a FOIA request, the agency may charge ernment for its share. The amount of the requester a reasonable fee equaling compensation shall be computed in the the full incremental cost of obtaining same manner as for equipment. -

Externalities in International Tax Enforcement: Theory and Evidence∗

Externalities in International Tax Enforcement: Theory and Evidence∗ Thomas Tørsløv (University of Copenhagen) Ludvig Wier (UC Berkeley) Gabriel Zucman (UC Berkeley and NBER) December 25, 2020 Abstract We show that the fiscal authorities of high-tax countries can lack the incentives to combat profit shifting to tax havens. Instead, they have incentives to focus their enforcement efforts on relocating profits booked by multinationals in other high-tax countries, crowding out the enforcement on transactions that shift profits to tax havens, and reducing the global tax payments of multinational companies. The predictions of our model are motivated and supported by the analysis of two new datasets: the universe of transfer price corrections conducted by the Danish tax authority, and new cross-country data on international tax enforcement. ∗Thomas Tørsløv: [email protected]; Ludvig Wier: [email protected]; Gabriel Zucman: [email protected]. We thank the Danish Tax Administration for data access and many conversations, the Editor, three referees, and numerous seminar and conference participants. Financial support from the FRIPRO program of the Research Council of Norway and from Arnold Ventures is gratefully acknowledged. The authors retain sole responsibility for the views expressed in this research. 1 Introduction Multinational firms can avoid taxes by shifting profits from high-tax to low-tax countries. A number of studies suggest that this profit shifting causes substantial losses of tax revenue (Criv- elli, de Mooij and Keen, 2015; Bolwijn et al., 2018; Clausing, 2016; Tørsløv et al., 2020). In principle, tax authorities in high-tax countries can attempt to reduce profit shifting by increas- ing the monitoring of intra-group transactions and enforcing more strongly the rules governing the pricing of these transactions.1 Why, despite the sizable revenue losses involved, does profit shifting nonetheless persist? This paper provides a novel answer to this question by studying the incentives faced by tax authorities.