Uniting the Voices Decision Making to Negotiate for Native Title in South Australia Judith Morrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grievability and Nuclear Memory | 379

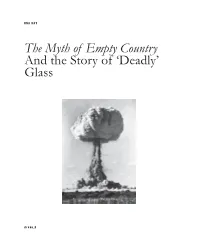

Grievability and Nuclear Memory | 379 Grievability and Nuclear Memory Jessie Boylan Nuclear Wounds Without grievability, there is no life, or, rather, there is something living that is other than life. Instead, “there is a life that will never have been lived,” sustained by no regard, no testimony, and ungrieved when lost. The apprehension of grievability precedes and makes possible the apprehension of precarious life. —Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (2009) ince 1945, nuclear weapons have been tested on all continents except for South America and Antarctica. Although “it is the nature of bombing to Sbe indiscriminate,”1 Aboriginal, Indigenous, and First Nations people have been the disproportionate victims of these weapons. They also continue to face nuclear waste dumps, uranium mines, and other nuclear projects on their land. This radioactive colonialism ensures that violence persists and is etched into the knowledge of people, place, and country, and that the single “event” of a nuclear detonation is far from over. Official records provide ample evidence to document how state policies, practices, and attitudes marked Aboriginal people as not fully human. For example, the Maralinga nuclear test site in Australia was “chosen on the false assumption that the area was not used by its traditional Aboriginal owners.”2 People living downwind (“downwinders”) of the Nevada Test Site in Utah during the US atomic weapons testing program,3 including First Nations communities, were considered “a low-use segment of the population.”4 These racist assumptions and statements, one tiny example from the archive of the nuclear landscape, constructed the people (and the lands they inhabited) as disposable. -

A Needs-Based Review of the Status of Indigenous Languages in South Australia

“KEEP THAT LANGUAGE GOING!” A Needs-Based Review of the Status of Indigenous Languages in South Australia A consultancy carried out by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, South Australia by Patrick McConvell, Rob Amery, Mary-Anne Gale, Christine Nicholls, Jonathan Nicholls, Lester Irabinna Rigney and Simone Ulalka Tur May 2002 Declaration The authors of this report wish to acknowledge that South Australia’s Indigenous communities remain the custodians for all of the Indigenous languages spoken across the length and breadth of this state. Despite enormous pressures and institutionalised opposition, Indigenous communities have refused to abandon their culture and languages. As a result, South Australia is not a storehouse for linguistic relics but remains the home of vital, living languages. The wisdom of South Australia’s Indigenous communities has been and continues to be foundational for all language programs and projects. In carrying out this project, the Research Team has been strengthened and encouraged by the commitment, insight and linguistic pride of South Australia’s Indigenous communities. All of the recommendations contained in this report are premised on the fundamental right of Indigenous Australians to speak, protect, strengthen and reclaim their traditional languages and to pass them on to future generations. * Within this report, the voices of Indigenous respondents appear in italics. In some places, these voices stand apart from the main body of the report, in other places, they are embedded within sentences. The decision to incorporate direct quotations or close paraphrases of Indigenous respondent’s view is recognition of the importance of foregrounding the perspectives and aspirations of Indigenous communities across the state. -

Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies

Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies Historical and anthropological perspectives Indigenous Participation in Australian Economies Historical and anthropological perspectives Edited by Ian Keen THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ip_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Indigenous participation in Australian economies : historical and anthropological perspectives / edited by Ian Keen. ISBN: 9781921666865 (pbk.) 9781921666872 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Economic conditions. Business enterprises, Aboriginal Australian. Aboriginal Australians--Employment. Economic anthropology--Australia. Hunting and gathering societies--Australia. Australia--Economic conditions. Other Authors/Contributors: Keen, Ian. Dewey Number: 306.30994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: Camel ride at Karunjie Station ca. 1950, with Jack Campbell in hat. Courtesy State Library of Western Australia image number 007846D. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements. .vii List.of.figures. ix Contributors. xi 1 ..Introduction. 1 Ian Keen 2 ..The.emergence.of.Australian.settler.capitalism.in.the.. nineteenth.century.and.the.disintegration/integration.of.. Aboriginal.societies:.hybridisation.and.local.evolution.. within.the.world.market. 23 Christopher Lloyd 3 ..The.interpretation.of.Aboriginal.‘property’.on.the. -

Information for Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands Applicants

Money Mob Talkabout Information for Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands Applicants Money Mob Talkabout is not-for-profit organization providing financial capability and counselling programs in the APY Lands in northern South Australia. We have three offices in the communities of Ernabella (Pukatja), Amata and Kanpi. We are also a Service SA and Centrelink agent at our Pukatja Office and Centrelink agent at our Kanpi office, as well as providing support to local community councils in Pukatja and Kanpi. 1 Contents 1. How We Work Page 3 2. Money Mob Talkabout Vision, Mission, Values and Goals Page 3 3. Money Mob Talkabout Program Overview Page 5 4. Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands Overview Page 6 4.1 Communication 4.2 Medical Care 4.3 Immunisations 4.4 Preparing a Home First Aid Kit 4.5 Police 4.6 Schooling and Risk to Children 4.7 Shopping 4.8 Car Repairs 4.9 Petrol 4.10 Other Amenities 5. Money Mob Offices Page 9 5.1 Amata Office 5.2 Pukatja Office 6. APY Lands Map Page 14 7. Adjusting to Community Life & Fitting in Page 14 7.1 Personal Safety 7.2 Relationships between Genders 7.3 Same Sex Relationships, Transgender People 7.4 Aggressive Clients/Difficult Situations 7.5 Family and Domestic Violence, Substance Abuse, Gambling 7.6 Community Violence 7.7 Animals 7.8 Keeping Yourself Healthy 7.9 Signs of Vicarious Trauma 8. Staff Accommodation Page 18 8.1 Sharing Accommodation and Visitors 9. Accommodation when Travelling for Work Page 19 10. Further Information and Resources Page 21 2 How We Work Money Mob Talkabout takes a strong community development approach; we work alongside people to empower them and teach them independent skills – we do not “do for.” We believe that each person has diverse strengths and inherent dignity as a human being. -

The Myth of Empty Country and the Story of 'Deadly' Glass

U N A R A Y The Myth of Empty Country And the Story of ‘Deadly’ Glass l d ı v a n_9 In order for Country to be living, people need to be there.1 Yhonnie Scarce, 2020 AS FAR AS THE EYE WILL SEE When British scientists were surveying international locations for their atomic tests in the early 1950s, they were looking for empty land, country devoid of human life. Culturally habituated to see what they wanted to see, they found what they wanted to find: ‘empty’ land and sea off the north- west coast and inland deserts of Australia which proved ideal for their clandestine military purposes. This ‘find’ echoed James Cook’s ‘discovery’ when he claimed the ‘empty land’ of the Australian continent for the British Crown under Europe’s international legal doctrine of terra nullius in 1770. In the mid-twentieth century, in the wake of their Second World War defeat in Singapore and the military power demonstrated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United Kingdom’s aspiration was to keep the fire of Empire burning: keeping pace with the United States and Russia in their escalating arms race was a matter of urgency and Commonwealth honour. Today, such misappropriations and misdirected ambitions are often massed together under the malevolent banner of colonialism. This unresolved and violent history between Australia’s first people and British colonisers remains a cloud in its collective skies and a scar on its soil; a past complicated by the matrilineal rift between Britain and its bastard colony offspring with its own history of secrets, denials and dismissals. -

Shifting State Constructions of Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara’ Referred to in the Title

Shifting State Constructions of Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara: Changes to the South Australian Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act 1981-2006 DEIRDRE TEDMANSON A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY February 2016 Declaration of Originality I certify that this thesis does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university; and that to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. Signed: On: 20/10/2016 ii Acknowledgements There are many people I would like to acknowledge for their support on this journey. First and foremost, I would like to thank Principal Supervisor and Chair of my Supervisory Panel, Dr Will Sanders, Senior Fellow at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR) at ANU for his constancy throughout my candidature. From our first discussions to final submission, you have challenged, advised, guided and provided unfailing support and it is very much appreciated – thankyou. Thanks also to supervisory panel members, Professor Jon Altman for generosity of spirit and inspiring ideas; Professor Tim Rowse for important early theoretical insights; Professor Richard Mulgan also for helpful early discussions. Thanks also to Professor Mick Dodson for timely clarifications and Professor Larissa Behrendt for insights into legal issues. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Director Jerry Schwab and everyone at CAEPR, staff, academics, colleagues, students all - for making me welcome throughout my time with the Centre. Thanks also to all my wonderful friends and colleagues for your encouragement. -

Testing the Bomb: Maralinga and Australian

BLACK MIST BURNT COUNTRY Testing The Bomb: Maralinga and Australian Art AN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE FOR YEARS 9–12 BLACK MIST BURNT COUNTRY Testing The Bomb: Maralinga and Australian Art AN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE FOR YEARS 9–12 “We seen this smoke…it was black, greasy, sort of shiny…it was rolling up to us through the mulga. We thought it was a mamu, a devil spirit. The old people got their woomeras to wave it away, but it was a very strong mamu.” Yami Lester – Yankunytjatjara man and victim of the Emu Fields atomic tests in 1953. The Black Mist Burnt Country Timeline of Nuclear Testing in Australia 2 exhibition explores the British The Development of the A-Bomb 4 atomic testing that occurred at the Monte Bello Islands (WA), Emu Field The Bombing of Hiroshima 8 (SA) and Maralinga (SA) between 1952 and 1963, and reflects British Tests in Australia 13 on the subsequent human and environmental impact of the tests. Maralinga: Ground Zero 16 Indigenous Culture and Land Rights 20 Each chapter of the Black Mist Burnt Country story is linked to a Impact on Country and Environment 24 key artwork. When you see this symbol, stop in front of the relevant The Clean Up 27 piece and complete the analysis task. Victims and Survivors 30 ‘Ban the Bomb’: The Australian Anti-Nuclear 33 Movement Australia’s Nuclear Future? 36 Timeline of Nuclear Testing in Australia September 1942 to undertake atomic weapons tests. The general US General Leslie Groves assigned to command public is largely unaware of the nature and risks of secret Manhattan Project. -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB BRITAIN’S PACIFIC H-BOMB TESTS GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB BRITAIN’S PACIFIC H-BOMB TESTS NIC MACLELLAN PACIFIC SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Maclellan, Nic, author. Title: Grappling with the bomb : Britain’s Pacific H-bomb tests / Nicholas Maclellan. ISBN: 9781760461379 (paperback) 9781760461386 (ebook) Subjects: Operation Grapple, Kiribati, 1956-1958. Nuclear weapons--Great Britain--Testing. Hydrogen bomb--Great Britain--Testing. Nuclear weapons--Testing--Oceania. Hydrogen bomb--Testing--Oceania. Nuclear weapons testing victims--Oceania. Pacific Islanders--Health and hygiene--Oceania. Nuclear explosions--Environmental aspects--Oceania. Nuclear weapons--Testing--Environmental aspects--Oceania. Great Britain--Military policy. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image: Adapted from photo of Grapple nuclear test. Source: Adi Sivo Ganilau. This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of illustrations . vii Timeline and glossary . xi Maps . xxiii Introduction . 1 1 . The leader—Sir Winston Churchill . .19 2 . The survivors—Lemeyo Abon and Rinok Riklon . 39 3 . The fisherman—Matashichi Oishi . 55 4 . The Task Force Commander—Wilfred Oulton . 69 5 . The businessman—James Burns . 81 6 . The pacifist—Harold Steele . 91 Interlude—On radiation, safety and secrecy . 105 7 . The Chief Petty Officer—Ratu Inoke Bainimarama . -

Book Reviews10.Pdf

BOOK REVIEWS Daughters of the Dreaming. By Diane Bell. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1993. First published 1983. Second edition with new foreword and epilogue. Pp. 342. Black and white illustrations, bibliography, index. $1.95 p.b. In this, the second edition of a monograph first published in 1983, the original text is unaltered except for minor corrections, but Diane Bell has added a short foreword and a 27- page epilogue. I reviewed the original text in Aboriginal History (vol. 8) and stand by what I wrote then:- 'Her book ... represents a major contribution to our knowledge of past and present Aboriginal societies and demonstrates the significance of women in every aspect of community existence.' Since its publication a number of women have engaged in research into various aspects of the lives of Aboriginal women and have written MA or PhD theses of considerable importance. They have produced articles in books and journals, but no monographs. An outstanding collection about South Australian Aboriginal women edited by Peggy Brock was published in 1989 under the title Women, rites and sites: Aboriginal women's cultural knowledge. In her foreword to the new edition Bell explains that she had decided not to alter the original text (except for minor corrections) because this had historical relevance in reflecting some of the values of the early 1980s both in anthropology and in her own development. In her epilogue she describes some of the changes in anthropological theory particularly where the study of women's society is concerned. Much of the epilogue is a discussion of the development during the last ten years of feminist anthropological theory, a discussion which would be helpful for any woman embarking on fieldwork today. -

YAMI LESTER OAM – 24 August 1941 to 21 July 2017 R.I.P

YAMI LESTER OAM – 24 August 1941 to 21 July 2017 R.I.P. BY COOBER PEDY REGIONAL TIMES ON JULY 22, 2017 • Yami Lester OAM – 24 August 1941 to 21 July 2017 R.I.P. It is with great sadness that the family of Yami Lester announce the passing of Yami Lester (Poppa Yami), Yankunytjatjara leader and Elder, Land Rights and anti-nuclear campaigner on 21 July 2017, age 75.Yami was born in the early 1940s at Walkinytjanu Creek (Wal-kin- jahnu) an outstation on Granite Downs Station in the far north of South Australia. When the atomic bomb went off at Emu Field (the first test on the mainland), Yami was about ten years of age and through life would re-tell with clarity and sadness of his family being blanketed in the toxic fallout and the sickness and death that followed. As a stockman and skilled horseman, Yami spent his early years working on pastoral properties across South Australia until losing his eyesight as a teenager and later becoming completely blind – the consequence of dust from the nuclear bomb. He was a member of the Aboriginal Advancement League, was drawn to social work assisting families in need with health and education during work with the United Mission and was instrumental, together with the late Reverend Jim Downing, in the establishment of the Institute for Aboriginal Development in Alice Springs and the Pitjantjatjara Land Council. As a professional interpreter and cultural broker he worked in the law courts making sure the voice of Anangu was understood. Yami made it his life’s work to campaign locally, nationally and internationally for the clean- up of Maralinga following the Nuclear Atomic Bomb testing by the British in the 1950s and 60s, for a Royal Commission and for compensation for destruction and contamination of country and the dispossession of Anangu. -

New Claim for the South East of SA

Aboriginal Way www.nativetitlesa.org Issue 68, Spring 2017 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Above: Bunggul (ceremonial dancing) for opening of Garma 2017. Read full article on page 4. New claim for the South East of SA Native Title claims for areas in traditional law and customs and descendants “I congratulate that community and That overlap area has been excised from the South East of South Australia of particular people who lived in that area. am pleased that the process to have the Ngarrindjeri Claim and mediation has have been approved by community their native title recognised has begun” commenced, as the Ngarrindjeri Claim is The claim was authorised at a meeting members and lodged by SA Native said Mr Thomas heading for a Consent Determination in in Mount Gambier and lodged on Title Services (SANTS). coming months. 4 August 2017. SANTS Senior Anthropologist Robert The First Nations of the South East Claim Graham will prepare a Native Title “The lodging of this claim marks #1 and #2 cover areas near Keith to the SA Native Title Services CEO Keith report as required by the court. significant progress in the resolution coast and across to the Victorian border, Thomas welcomed the authorisation and of native title across the state” The claims are now awaiting registration including the towns of Mount Gambier, lodging of the claim. Mr Thomas said. by the Federal Court. The First Nations of Penola and Lakes Bonney, George and Eliza. “They’ve been waiting a long time, there the South East Claim #2 has some parts “This is a large claim area and leaves Native title holders are held to be First have been limited resources available to which overlap the existing Ngarrindjeri only some small areas of the state yet Nations of the South East people under prepare this application” he said. -

Maralinga: the a the Maralinga: Angu Account of the Land, Revealing Their Their Revealing Land, the of Account Angu N a an with Begins Story Angu N

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Years 7/8 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| histories and cultures ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Maralinga: The Anangu Story, by the Oak Valley and Yalata communities, with Christobel Mattingley TYPE OF TEXT: NON-FICTION, PICTURE BOOK ORIGIN: AUSTRALIA PUBLICATION DETAILS: ALLEN AND UNWIN, 2009 UNIT WRITTEN BY: DEB MCPHERSON Text synopsis Maralinga: The Anangu Story is a non-fiction picture book that is the result of a collaboration between two closely linked South Australian Aboriginal communities, Oak Valley and Yalata, and a popular children’s author, Christobel Mattingley. The story is about the Anangu—their history, their culture and the effects of nuclear weapons testing on their lands. The Indigenous people of north-western South Australia call themselves ‘Anangu’, which simply means ‘people’. European