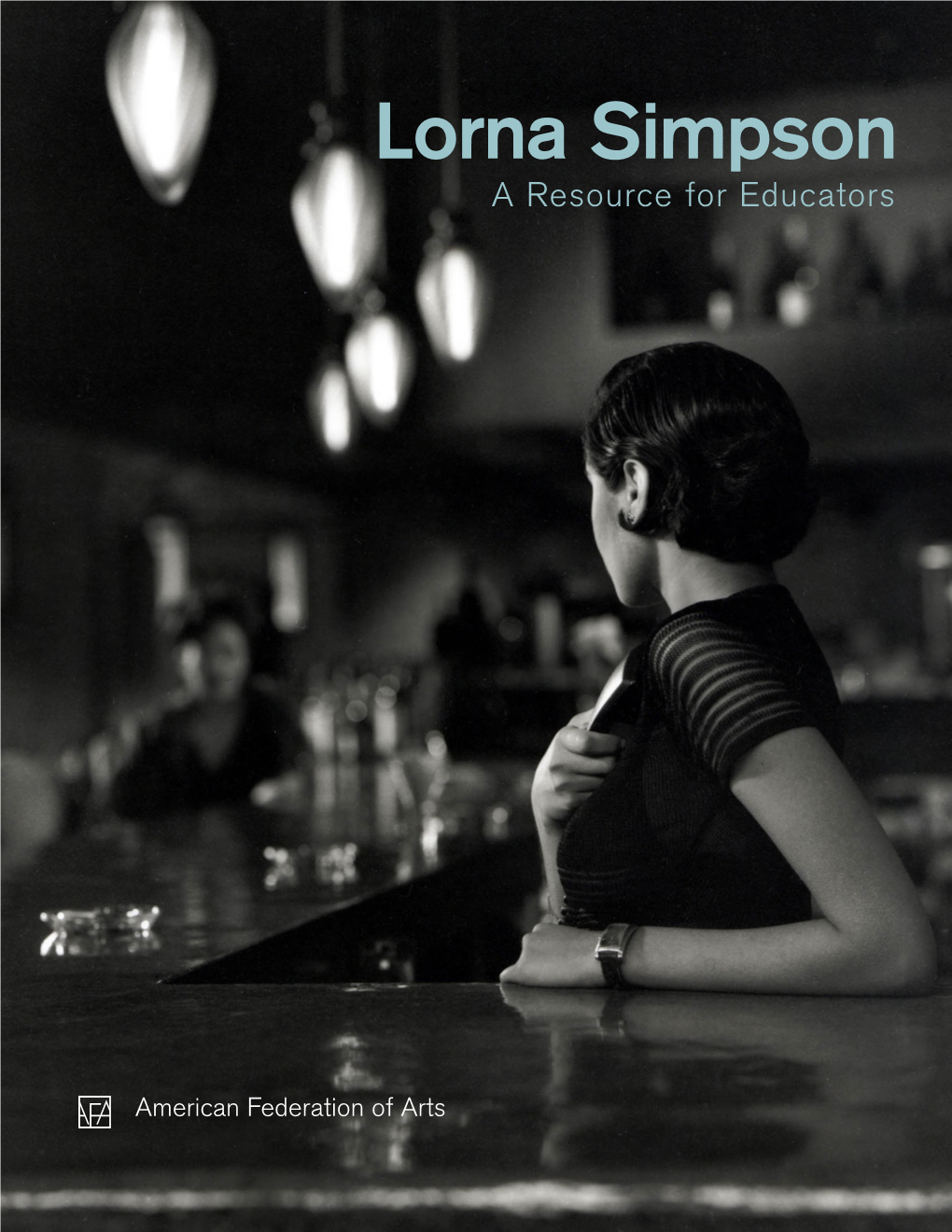

Lorna Simpson a Resource for Educators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an Intergenerational Exhibition of Works from Thirty-Seven Artists, Conceived by Curator Okwui Enwezor

NEW MUSEUM PRESENTS “GRIEF AND GRIEVANCE: ART AND MOURNING IN AMERICA,” AN INTERGENERATIONAL EXHIBITION OF WORKS FROM THIRTY-SEVEN ARTISTS, CONCEIVED BY CURATOR OKWUI ENWEZOR Exhibition Brings Together Works that Address Black Grief as a National Emergency in the Face of a Politically Orchestrated White Grievance New York, NY...The New Museum is proud to present “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an exhibition originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019) for the New Museum, and presented with curatorial support from advisors Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash. On view from February 17 to June 6, 2021, “Grief and Grievance” is an intergenerational exhibition bringing together thirty-seven artists working in a variety of mediums who have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration, and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of racist violence experienced by Black communities across America. The exhibition further considers the intertwined phenomena of Black grief and a politically orchestrated white grievance, as each structures and defines contemporary American social and political life. Included in “Grief and Grievance” are works encompassing video, painting, sculpture, installation, photography, sound, and performance made in the last decade, along with several key historical works and a series of new commissions created in response to the concept of the exhibition. The artists on view will include: Terry Adkins, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kevin Beasley, Dawoud Bey, Mark -

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Jason Moran STAGED Luhring Augustine Is Pleased to Announce

Jason Moran STAGED April 29 – July 30, 2016 Opening reception: Thursday, April 28, 6-8pm Luhring Augustine is pleased to announce the opening of STAGED, the first solo exhibition by the musician/composer/artist Jason Moran, in our Bushwick gallery. Moran's rich and varied work in both music and visual art mines entanglements in American cultural production. He is deeply invested in complicating the relationship between music and language, exploring ideas of intelligibility and communication. In his first gallery exhibition, Moran will continue to investigate the overlaps and intersections of jazz, art, and social history, provoking the viewer to reconsider notions of value, authenticity, and time. STAGED will include a range of objects and works on paper, including two large-scale sculptures with audio elements from Moran’s STAGED series that were recently exhibited in the 56th Biennale di Venezia. Based on two historic New York City jazz venues that no longer exist (the Savoy Ballroom and the Three Deuces), the sculptures are hybrids of reconstructions and imaginings. Works on paper and smaller objects will be in dialogue with the stage sculptures on many levels: citing performance and process, employing sound, and exploiting the visual history of jazz in America. Moran was born in Houston, TX in 1975. He was made a MacArthur Fellow in 2010 and is currently the Artistic Director for Jazz at The Kennedy Center in Washington DC; he also teaches at the New England Conservatory in Boston, MA. Moran’s activities comprise both his work with masters of jazz such as Charles Lloyd, the late Sam Rivers, Henry Threadgill, Cassandra Wilson, and his trio The Bandwagon (with drummer Nasheet Waits and bassist Tarus Mateen) as well as a number of partnerships with visual artists, including Stan Douglas, Theaster Gates, Joan Jonas, Glenn Ligon, Adam Pendleton, Adrian Piper, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker. -

Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact Audrey M

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Museum Studies Theses History and Social Studies Education 5-2019 Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact Audrey M. Clark State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Nancy Weekly, Burchfield Penney Art Center Collections Head First Reader Cynthia A. Conides, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Coordinator of the Museum Studies Program Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls, Ph.D., Chair and Professor of History To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to https://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Clark, Audrey M., "Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact" (2019). Museum Studies Theses. 21. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses/21 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons I Abstract This paper aims to explore the history of women within the context of the museum institution; a history that has often encouraged collaboration and empowerment of marginalized groups. It will interpret the history of women and museums and the impact on the institution by surveying existing literature on feminism and museums and the biographies of a few notable female curators. As this paper hopes to encourage global thinking, museums from outside the western sphere will be included and emphasized. Specifically, it will look at organizations in the Middle East and that exist in only a digital format. This will lead to an analysis of today’s feminist principles applied specifically to the museum and its link with online platforms. -

Lorna Simpson

Teacher Resource Packet Lorna Simpson: Gathered January 28–August 21, 2011 About the Artist Lorna Simpson: Gathered Born in 1960 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, Lorna Simpson attended the High School of Art and Design and the School of Visual Arts in New York and received her MFA from the University of California, San Diego. Simpson studied documentary photography in college but became disenchanted with what she considered to be the role of the viewer and photographer as voyeur (someone who spies on people engaged in intimate behaviors). To complicate this role, she began to produce photographs that hide or obscure the faces of her subjects, changing the power balance between the viewer and the subject of the photograph. Her first critical recognition came in the mid-1980s, for a series of large- scale artworks that combined photographs and text to challenge views of gender, race, identity, culture, history, and memory. Simpson often draws her subject matter from African American history and issues of identity. She uses the human figure to examine her ideas of objective “truth” and the ways in which gender and culture shape our interactions, relationships, and experiences. About the Exhibition Simpson’s work in Lorna Simpson: Gathered focuses on the themes of identity and the cultural weight of history. The exhibition explores the artist’s ongoing interest in using photographs from African American history to call into question the perspective of photographs as objective truth. For example, in the series ’57/’09, Simpson pairs found images with her own photographs to create new contexts and meaning. This ambitious project includes hundreds of photographs of African Americans from the late 1950s that Simpson collected from eBay. -

LORNA SIMPSON-Bibliography-2018

LORNA SIMPSON SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY MONOGRAPHS Centric 38: Lorna Simpson. Exhibition brochure. Long Beach: University Art Museum, California State University, 1990. Text by Yasmin Ramirez Harwood. Compostela: Lorna Simpson. Exhibition catalogue. Santiago de Compostela, Spain: Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea, 2004. Texts by Miguel Fernández-Cid and Marta Gili. Ink. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Salon 94, 2008. Interview with Lorna Simpson by Glenn Ligon. Lorna Simpson. London: Phaidon, 2002. Contributions by Thelma Golden, Chrissie Iles, Kellie Jones, Suzan-Lori Parks, Lorna Simpson, and Deborah Willis. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition brochure. New York: Josh Baer Gallery, 1989. Text by Kellie Jones. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition brochure. Hamilton, NY: Gallery of the Department of Art and Art History, Dana Art Center, Colgate University, 1991. Text by Coco Fusco. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition brochure. Elkins Park, PA: Tyler School of Art Galleries, Temple University, 1992. Text by Cheryl Gelover. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition brochure. Vienna: Wiener Secession, 1995. Text by bell hooks. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Abrams in association with the American Federation of Arts, 2006. Text by Okwui Enwezor, with contributions by Hilton Als, Thelma Golden, Isaac Julien, Shamim M. Momin, and Helaine Posner Lorna Simpson. Exhibition catalogue. Salamanca, Spain: Centro de Arte de Salamanca, Consorcio Salamanca, 2002. Texts by Leslie Camhi, Marta Gili, and Eungie Joo. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition brochure. Wooster, OH: College of Wooster Art Museum, 2004. Text by John Siewert. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition catalogue. San Francisco: Friends of Photography, 1992. Text by Deborah Willis. Afterword by Andy Grundberg. Lorna Simpson. Exhibition catalogue. Munich, London and New York: DelMonico Books, Prestel Publishing, 2013. -

Lorna Simpson Unanswerable

HAUSER & WIRTH Press Release Lorna Simpson Unanswerable Hauser & Wirth London 1 March – 28 April 2018 Opening: Wednesday 28 February 2018, 6 – 8 pm Lorna Simpson’s inaugural exhibition at Hauser & Wirth London, ‘Unanswerable’, features new and recent work across three different media: painting, photographic collage and sculpture. Simpson came to prominence in the 1980s through her pioneering approach to conceptual photography, which featured striking juxtapositions of text and staged images and raised questions about the nature of representation, identity, gender, race and history. These concerns are reflected throughout the exhibition to present the artist’s expanding and increasingly multi-disciplinary practice today. Simpson continues to develop the language of the found image as a source for her work, incorporating photographs from her collection of vintage Ebony and Jet magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s. These publications focused on subjects of lifestyle, culture and politics from an African-American perspective and are credited with chronicling black lives and issues so sorely under-represented elsewhere in the media. The material has both a personal and a wider cultural significance for Simpson who describes how the magazines, ‘informed my sense of thinking about being black in America and are both a reminder of my childhood and a lens through which to see the past fifty years of history.’ Through layering and collage, Simpson’s recent works reconfigure imagery of the female form and reflect the artist’s ongoing exploration of, and response to, contemporary culture and American life today. An installation, entitled ‘Unanswerable’ (2018), is composed of over 40 individual photo collages each of which is unique and created from original source material and archive photography. -

Press Release

Press Release December 2010 Brooklyn-Based Artist and Photographer Lorna Simpson to Have Solo Exhibition at Brooklyn Museum On View January 28 through August 21, 2011 Lorna Simpson: Gathered presents photographic and other works that explore the artist’s interest in the interplay between fact and fiction, identity, and history. Through works that incorporate hundreds of original and found vintage photographs of African Americans that she collected from eBay and flea markets, Simpson undermines the assumption that archival materials are objective documents of history. In one series, titled May June July August ‘57/‘09, comprising 123 vintage and contemporary black-and- white photographs, Simpson juxtaposes images of young African American women (and an occasional male figure) who posed for pinups in Los Angeles in 1957 with self-portraits in which the artist acts as a doppelganger for each model. She replicates with precise detail the poses and settings of the original photographs, arranging the work in grid patterns. Linking the historical photographs with her staged responses creates a fictionalized narrative in which the two characters appear to be linked across history in a shared identity or destiny. The exhibition also includes examples of Simpson’s series of installations of black-and-white photo-booth portraits of African Americans from the Jim Crow era and a new film work. Lorna Simpson was born in 1960 in Brooklyn, New York. She received her BFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts, New York, and her MFA from the University of California, San Diego. After beginning her career as a documentary photographer, Simpson received her first critical recognition in the mid-1980s for a series of large-scale works using photography and text to confront and challenge conventional interpretations of gender, identity, culture, history, and memory. -

African American Art Since 1950: Perspectives from the David C

African American Art Since 1950: Perspectives from the David C. Driskell Center Resource made possible through our partnerships with: Welcome to the Figge Art Museum’s Teacher Resource Guide These cards describe selected works from the exhibition. Use them to engage with the artwork, find facts about the artists, and facilitate learning. Resources are provided on each card for additional research. About the Exhibition In 1976, David C. Driskell curated the groundbreaking exhibition, Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950. The exhibition explored the depth and breadth of African American art, often marginalized by historical texts. It had massive influence on both the artists and the general public. The David C. Driskell Center has organized the exhibition, African American Art Since 1950, Perspectives from the David C. Driskell Center, as a response to Two Centuries. The exhibition explores the rising prominence and the complexity of African American art from the last 60 years. Many leading African American artists are featured in this exhibition including: Romare Bearden, Faith Ringgold, Jacob Lawrence, Betye Saar, Radcliffe Bailey, Kara Walker and Carrie Mae Weems. This exhibition gives a picture of the diversity of recent African American art, with its many approaches and media represented. The works explore various themes including: political activism, race, stereotypes, cultural and social identity, music, abstraction, among others. Featured Artists Radcliffe Bailey Romare Bearden Sheila Pree Bright Kevin Cole David C. Driskell Vanessa German Robin Holder Margo Humphrey Jacob Lawrence Kerry James Marshall Faith Ringgold Lorna Simpson Hank Willis Thomas Carrie Mae Weems Radcliffe Bailey Until I Die/Georgia Trees and the Upper Room, 1997 Color aquatint with photogravure and chin collé © 2011 Radcliffe Bailey Gift from the Jean and Robert E. -

Recent Video Work by Acclaimed Artist Lorna Simpson Shimmers on CAM's

Press contact: Eddie Silva 314.387.0405 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Recent video work by acclaimed artist Lorna Simpson shimmers on CAM’s facade for Street Views Lorna Simpson, Redhead, 2018. Single-channel digital animation video, 8 seconds on loop. © LornaSimpson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. May 5, 2021 (St. Louis, MO) - The Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM) presents Lorna Simpson: Heads, an exhibition of two recent digital animation videos by the acclaimed artist. In the two works, Blue Love (2020) and Redhead (2018), from her Ebony collage series, Simpson melds black-and-white photographs of women and men from vintage Ebony and Jet magazines, embellished with shimmering, flame-like watercolor hairdos. Lorna Simpson: Heads will be on view on CAM’s facade as part of Street Views, from dusk to midnight, September 3, 2021 through February 20, 2022. Simpson came to prominence in the 1980s as part of a generation of artists who utilized conceptual approaches in photography to challenge the credibility and assumed neutrality of images and language. Her most iconic works from this period depict people staged in a neutral studio, photographed from behind or in fragments— isolated from time or specificity of place. Simpson accompanies these images with her own texts. These powerful yet ambiguous works raise questions about the nature of representation, identity, gender, race, memory, and history. Since the late 1990s, Simpson has extended these concerns into a series of film and video installations. In her Ebony collage series, Simpson manipulates the photographs through extreme cropping and close-ups to emphasize parts of the bodies—in the case of Blue Love and Redhead, the subjects’ faces and hair. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title By Any Means Necessary: The Art of Carrie Mae Weems, 1978-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5th1n63r Author Searcy, Elizabeth Holland Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles By Any Means Necessary: The Art of Carrie Mae Weems, 1978-1991 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Elizabeth Holland Searcy 2018 © Copyright by Elizabeth Holland Searcy 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION By Any Means Necessary: The Art of Carrie Mae Weems, 1978-1991 by Elizabeth Holland Searcy Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Steven D. Nelson, Chair This dissertation examines the photography of Carrie Mae Weems (born 1953) and her exploration issues of power within race, class, and gender. It focuses on the period of 1978-1991, from her first major series, Family Pictures and Stories (1978- 1984), to And 22 Million Very Tired and Very Angry People (1991). In these early years of her career, Weems explores junctures of identity while levying a critique of American culture and its structures of dominance and marginalization. In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and Second Wave Feminism of the 1970s, scholars— particularly women of color—began looking seriously at the intersectional nature of identity and how it manifests in culture and lived experience. These issues are the central themes Weems’s career, and by looking at her early explorations this study provides critical context for her body of work. -

EXHIBITIONS at 583 BROADWAY Linda Burgess Helen Oji Bruce Charlesworth James Poag Michael Cook Katherine Porter Languag�

The New Museum of Contemporary Art New York TenthAnniversary 1977-1987 Library of Congress Calalogue Card Number: 87-42690 Copyright© 1987 The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. All Rights Reserved ISBN 0-915557-57-6 Plato's Cave, Remo Campopiano DESIGN: Victor Weaver, Ron Puhalsk.i'&? Associates, Inc. PRINTING: Prevton Offset Printing, Inc. INK: Harvey Brice, Superior Ink. PAPER: Sam Jablow, Marquardt and Co. 3 2 FROM THE PRESIDENT FROM THE DIRECTOR When Marcia Tu cker,our director,founded The New Museum of Contemporary Art, what were Perhaps the most important question The New Museum posed for itself at the beginning, ten the gambler's odds that it would live to celebrate its decennial? I think your average horse player would years ago, was "how can this museum be different?" In the ten years since, the answer to that question have made it a thirty-to-one shot. Marcia herself will, no doubt, dispute that statement, saying that it has changed, although the question has not. In 1977, contemporary art was altogether out of favor, and was the right idea at the right time in the right place, destined to succe�d. In any case, it did. And here it most of the major museums in the country had all but ceased innovative programming in that area. It is having its Te nth Anniversary. was a time when alternative spaces and institutes of contemporary art flourished: without them, the art And what are the odds that by now it would have its own premises, including capacious, of our own time might have.remained invisible in the not-for-profitcultural arena.