Stalled in the Mirror Stage: Why the Jack Goldstein and Gretchen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an Intergenerational Exhibition of Works from Thirty-Seven Artists, Conceived by Curator Okwui Enwezor

NEW MUSEUM PRESENTS “GRIEF AND GRIEVANCE: ART AND MOURNING IN AMERICA,” AN INTERGENERATIONAL EXHIBITION OF WORKS FROM THIRTY-SEVEN ARTISTS, CONCEIVED BY CURATOR OKWUI ENWEZOR Exhibition Brings Together Works that Address Black Grief as a National Emergency in the Face of a Politically Orchestrated White Grievance New York, NY...The New Museum is proud to present “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an exhibition originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019) for the New Museum, and presented with curatorial support from advisors Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash. On view from February 17 to June 6, 2021, “Grief and Grievance” is an intergenerational exhibition bringing together thirty-seven artists working in a variety of mediums who have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration, and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of racist violence experienced by Black communities across America. The exhibition further considers the intertwined phenomena of Black grief and a politically orchestrated white grievance, as each structures and defines contemporary American social and political life. Included in “Grief and Grievance” are works encompassing video, painting, sculpture, installation, photography, sound, and performance made in the last decade, along with several key historical works and a series of new commissions created in response to the concept of the exhibition. The artists on view will include: Terry Adkins, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kevin Beasley, Dawoud Bey, Mark -

Penelope Umbrico's Suns Sunsets from Flickr

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Image Commodification and Image Recycling: Penelope Umbrico's Suns Sunsets from Flickr Minjung “Minny” Lee CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/506 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Image Commodification and Image Recycling: Penelope Umbrico’s Suns from Sunsets from Flickr Submitted to the Faculty of the Division of the Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and Liberal Arts by Minjung “Minny” Lee New York, New York May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Minjung “Minny” Lee All rights reserved CONTENTS Acknowledgements v List of Illustrations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1. Umbrico’s Transformation of Vernacular Visions Found on Flickr 14 Suns from Sunsets from Flickr and the Flickr Website 14 Working Methods for Suns from Sunsets from Flickr 21 Changing Titles 24 Exhibition Installation 25 Dissemination of Work 28 The Temporality and Mortality of Umbrico’s Work 29 Universality vs. Individuality and The Expanded Role of Photographers 31 The New Way of Image-making: Being an Editor or a Curator of Found Photos 33 Chapter 2. The Ephemerality of Digital Photography 36 The Meaning and the Role of JPEG 37 Digital Photographs as Data 40 The Aura of Digital Photography 44 Photography as a Tool for Experiencing 49 Image Production vs. -

9780230341449 Copyrighted Material – 9780230341449

Copyrighted material – 9780230341449 THE (MOVING) PICTURES GENERATION Copyright © Vera Dika, 2012. All rights reserved. First published in 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the World, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978–0–230–34144–9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dika, Vera, 1951– The (moving) pictures generation : the cinematic impulse in downtown New York art and film / Vera Dika. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–230–34144–9 1. Art and motion pictures—New York (State)—New York— History—20th century. 2. Art, American—New York (State)— New York—20th century. 3. Experimental films—New York (State)—New York—History—20th century. I. Title. N72.M6D55 2012 709.0407—dc23 2011039301 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Integra Software Services First edition: April 2012 10987654321 Printed in the United States of America. Copyrighted material – 9780230341449 Copyrighted material – 9780230341449 Contents -

Download a Searchable PDF of This

Jack Goldstein; Distance Equals Control by David SaZZe This essay is offered as a compliment to the exhibition rather than an explication of specific works. The language used in this text is somewhat more general and anecdotal, and more given to metaphoric comparisons than what we have come to expect from art writing. I don't in this essay attempt to dissect a single ' - exemplar work, nor do I spend much time detailing the visual ,+ attributes of the works. This essay attempts instead to give a brief description of an ongoing process: the play of private fan- tasy, which itself grows out of the intersection of psychic necessity (desire)with the culturally available forms in which to voice that necessity (automaticity)becoming linked in a work of art to everyday, public images which then reenter and submerge themselves, via the appropriative nature of our attention, into a clouded pool of personal symbols. This three part process yields a two part result; a sense of control over what one has effected distance from, which is ironically expressed in a sense of anxiety embedded in the image used in a given work, and also a sense of sadness because of the loss one feels for the thing distanced. The result of this process is nostalgia for the present, which is the name given to a complex texture of imagizing in which mediation between extremes (differentiation) leads to a liberated use of symbol rather than more limited narrative notion of emblem. To consider this work at all involves thinking about a way to stand in relation to the use of images both rooted in and somewhat distanced from cultural seeing. -

Robert Longo

ROBERT LONGO Born in 1953 in Brooklyn, New York Lives in New York, New York EDUCATION 1975 BFA State University College, Buffalo, New York SELECTED ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2021 A House Divided, Guild Hall, East Hampton, New York 2020 Storm of Hope, Jeffrey Deitch, Los Angeles 2019 Amerika, Metro Pictures, New York Fugitive Images, Metro Pictures, New York When Heaven and Hell Change Places, Hall Art Foundation | Schloss Derneburg Museum, Germany 2018 Proof: Francisco Goya, Sergei Eisenstein, Robert Longo, Deichtorhallen Hamburg Them and Us, Metro Pictures, New York Everything Falls Apart, Capitan Petzel, Berlin 2017 Proof: Francisco Goya, Sergei Eisenstein, Robert Longo, Brooklyn Museum (cat.) Sara Hilden Art Museum, Tampere, Finland (cat.) The Destroyer Cycle, Metro Pictures, New York Let the Frame of Things Disjoint, Thaddaeus Ropac, London (cat.) 2016 Proof: Francisco Goya, Sergei Eisenstein, Robert Longo, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow (cat.) Luminous Discontent, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris (cat.) 2015 ‘The Intervention of Zero (After Malevich),’ 1991, Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf 2014 Gang of Cosmos, Metro Pictures, New York (cat.) Strike the Sun, Petzel Gallery, New York 2013 The Capitol Project, Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut Phantom Vessels, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg, Austria 2012 Stand, Capitain Petzel, Berlin (cat.) Men in the Cities: Fifteen Photographs 1980/2012, Schirmer/Mosel Showroom, Munich 2011 God Machines, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris (cat.) Mysterious Heart Galería -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Through September 30 Contact: Sandra Q

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE through September 30 Contact: Sandra Q. Firmin Curator, UB Art Galleries 716.645.0570 [email protected] UB Anderson Gallery is pleased to present Fifty at Fifty: Select Artists from the Gerald Mead Collection Opening Public Reception: Saturday, August 18, 6-8 pm The exhibition is free and open to the public and will be on view through September 30, 2012. Fifty at Fifty: Select Artists from the Gerald Mead Collection is a survey exhibition featuring 86 works in all media by 50 of the most significant historical and contemporary artists associated with Western New York. The selection by the collector was guided by the artists’ art historical imprint as measured by the inclusion of their artwork in several major museum collections worldwide such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Tate Gallery, and the Centre Georges Pompidiou, among others. The exhibition has been organized on the occasion of noted collector and UB alumnus Gerald Mead’s 50th birthday. Since he began collecting in 1987, Mead has researched and assembled an art collection of more than 670 works by over 600 artists who were born or have lived in the Western New York region. His intent is to form an encyclopedic collection of noteworthy artists affiliated with organizations such as the Buffalo Society of Artists, Patteran Society, Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center, CEPA, and Big Orbit Gallery. He also collects the work of educators and alumni of the Art Institute of Buffalo, University at Buffalo, and Buffalo State College. -

Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey. Lives and works in Los Angeles and New York. EDUCATION 1966 Art and Design, Parsons School of Design, New York 1965 Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021-2023 Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York] [forthcoming] [catalogue forthcoming] 2019 Barbara Kruger: Forever, Amorepacific Museum of Art (APMA), Seoul [catalogue] Barbara Kruger - Kaiserringträgerin der Stadt Goslar, Mönchehaus Museum Goslar, Goslar, Germany 2018 Barbara Kruger: 1978, Mary Boone Gallery, New York 2017 Barbara Kruger: FOREVER, Sprüth Magers, Berlin Barbara Kruger: Gluttony, Museet for Religiøs Kunst, Lemvig, Denmark Barbara Kruger: Public Service Announcements, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2016 Barbara Kruger: Empatía, Metro Bellas Artes, Mexico City In the Tower: Barbara Kruger, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 2015 Barbara Kruger: Early Works, Skarstedt Gallery, London 2014 Barbara Kruger, Modern Art Oxford, England [catalogue] 2013 Barbara Kruger: Believe and Doubt, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria [catalogue] 2012-2014 Barbara Kruger: Belief + Doubt, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC 2012 Barbara Kruger: Questions, Arbeiterkammer Wien, Vienna 2011 Edition 46 - Barbara Kruger, Pinakothek -

Course Catalog

2019 COURSE CATALOG SPRING THE GLASSELL SCHOOL OF ART STUDIO SCHOOL µ˙The Museum Of Fine Arts, Houston mfah.org/studioschool Cover: Photograph by Allyson Huntsman WELCOME We are delighted to present the spring catalog, with course selections for the second semester in the magnificent Glassell School building. The enthusiasm generated by our wonderful facilities was tangible this fall semester, with the students inspired by their new environment. And we have just begun! Now that we are fully moved in and completely operational, look for additional exciting opportunities to learn about art, explore your own creativity, and develop the skills to express yourself. We are offering several innovative courses this spring semester, including metalworking; an advanced critique course; and an art history class dedicated to Vincent van Gogh that complements the special exhibition Vincent van Gogh: His Life in Art, on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, March 10 through June 27, 2019. Along with these recent additions, we continue with a full curriculum of 2-D and 3-D programs, enhanced by updated equipment and studios. We also offer more chances to explore digital media, both in focused classes and integrated into more traditional media. Come visit us and take a class at the new Glassell, where we have excellent teaching artists and scholars, plus exceptional facilities on the campus of a major museum. Joseph Havel Director, The Glassell School of Art The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 1 SPRING 2019 Contents Academic Calendar 4 General Information November 12–December 3 Preregistration for current students for spring 4 Admissions 2019 semester 6 Tuition Discounts for MFAH Members January 15–16 11:00 a.m.—6:00 p.m. -

Gretchen Bender

GRETCHEN BENDER Born 1951, Seaford, Delaware Died 2004 EDUCATION 1973 BFA University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill SELECTED ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 So Much Deathless, Red Bull Arts, New York 2017 Living With Pain, Wilkinson Gallery, London 2015 Tate Liverpool; Project Arts Centre, Dublin Total Recall, Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin 2013 Tracking the Thrill, The Kitchen, New York Bunker 259, New York 2012 Tracking the Thrill, The Poor Farm, Little Wolf, Wisconsin 1991 Gretchen Bender: Work 1981-1991, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, New York; traveled to Alberta College of Art, Calgary; Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art 1990 Donnell Library, New York Dana Arts Center, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York 1989 Meyers/Bloom, Los Angeles Galerie Bebert, Rotterdam 1988 Metro Pictures, New York Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 1987 Total Recall, The Kitchen, New York; Moderna Museet, Stockholm 1986 Nature Morte, New York 1985 Nature Morte, New York 1984 CEPA Gallery, Buffalo 1983 Nature Morte, New York 1982 Change Your Art, Nature Morte, New York SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 Bizarre Silks, Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, etc., Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland Glasgow International 2019 Collection 1970s—Present, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Dumping Core; on view through Spring 2021) 2018 Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston; traveled to University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor Expired Attachment, Mx Gallery, New York Art in Motion. 100 Masterpieces with and through Media. -

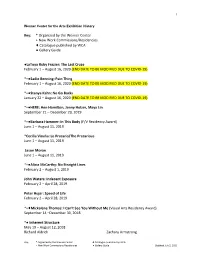

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

David Zwirner Is Pleased to Present an Exhibition of New Works by Sherrie Levine, on View at 537 West 20Th Street in New York

David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of new works by Sherrie Levine, on view at 537 West 20th Street in New York. This will be the gallery’s first exhibition with the artist since she joined in 2015. Levine’s work engages many of the core tenets of postmodern art, challenging notions of originality, authenticity, and identity. Since the late 1970s, she has created a singular and complex oeuvre using a variety of media, including photography, painting, and sculpture. Many of her works are explicitly appropriated from the modernist canon, while others are more general in their references, assimilating art historical interests and concerns rather than specific objects. Deeply interested in the process of artistic creation and in the contested notion of progress within art history, her work forthrightly acknowledges its existence as the product of what precedes it. The exhibition debuts an installation in which groups of monochrome paintings on mahogany are paired with refrigerators. The color of each painting derives from the nudes by Impressionist artist Auguste Renoir, and revisits a technique Levine first employed in 1989 with her Meltdown series of woodcut prints, where an averaging algorithm was used to create a checkerboard composition based on modernist artists’ iconic paintings. In a comment on the new installation, the artist notes: “The World of Interiors is my favorite shelter magazine. Often, there is a SMEG advertisement. SMEG is an Italian company that manufactures refrigerators in a retro style and saccharine colors. I thought it would be interesting to pair them with some monochrome paintings of mine, After Renoir Nudes, which are in fleshy shades. -

Jason Moran STAGED Luhring Augustine Is Pleased to Announce

Jason Moran STAGED April 29 – July 30, 2016 Opening reception: Thursday, April 28, 6-8pm Luhring Augustine is pleased to announce the opening of STAGED, the first solo exhibition by the musician/composer/artist Jason Moran, in our Bushwick gallery. Moran's rich and varied work in both music and visual art mines entanglements in American cultural production. He is deeply invested in complicating the relationship between music and language, exploring ideas of intelligibility and communication. In his first gallery exhibition, Moran will continue to investigate the overlaps and intersections of jazz, art, and social history, provoking the viewer to reconsider notions of value, authenticity, and time. STAGED will include a range of objects and works on paper, including two large-scale sculptures with audio elements from Moran’s STAGED series that were recently exhibited in the 56th Biennale di Venezia. Based on two historic New York City jazz venues that no longer exist (the Savoy Ballroom and the Three Deuces), the sculptures are hybrids of reconstructions and imaginings. Works on paper and smaller objects will be in dialogue with the stage sculptures on many levels: citing performance and process, employing sound, and exploiting the visual history of jazz in America. Moran was born in Houston, TX in 1975. He was made a MacArthur Fellow in 2010 and is currently the Artistic Director for Jazz at The Kennedy Center in Washington DC; he also teaches at the New England Conservatory in Boston, MA. Moran’s activities comprise both his work with masters of jazz such as Charles Lloyd, the late Sam Rivers, Henry Threadgill, Cassandra Wilson, and his trio The Bandwagon (with drummer Nasheet Waits and bassist Tarus Mateen) as well as a number of partnerships with visual artists, including Stan Douglas, Theaster Gates, Joan Jonas, Glenn Ligon, Adam Pendleton, Adrian Piper, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker.