Bulletin 50 – 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E January 2020 (Pdf)

Stratford St Mary Higham Holton St Mary Raydon Quartet The Parish Magazine January 2020 Issue 377 Real Christmas tree Babergh District Council has recycling launched the ‘Tree for Life’ initiative - they are offering families a tree to mark the arrival of every new child. For more information, go to: https://www.midsuffolk.gov.uk/ environment/tree-for-life/ Babergh District Council will recycle your real Christmas tree for free! If you have a garden waste bin all you need to do is leave your real Christmas tree (without decorations or pot) beside your brown bin for Power Cut? Call 105 | The collection throughout January. New Free Way to Report Issues If you don't - not a problem - you can recycle your tree at any of our www.powercut105.com collection points listed on our website. Experiencing a power cut? No matter who your provider is, 105 is Large trees (more than 7 ft tall, 3 the new number to call to get help inch trunk) can only be collected via and advice, free of charge on a collection point or at any of mobile and landlines. You can also Suffolk's household recycling call 105 with any welfare concerns centres. related to a power cut, or if you are worried about the safety of over or underground electricity cables or substations. You can place items for sale or wanted on the Small Ads Pin Board for free. Just email [email protected] with your advert. We will place it for one month space permitting. Small Ads pin board The Quartet Diary January April 4 Tea and Singing, SSM 4 RDGC Spring Show Raydon 8 HSM Parish Council -

Walking in Nayland

The Dedham Vale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty The Dedham Vale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is one of Britain’s finest landscapes. It extends from the Stour estuary in the east to Wormingford in the west. A wider project area extends along the Stour Valley to Walking in the Cambridgeshire border. The AONB was designated in 1970 and covers almost 35 square miles/90 square kms. The outstanding landscape includes ancient woodland, farmland, rivers, meadows and attractive villages. Visiting Constable Country Nayland Ordnance Survey Explorer Map No. 196 Public transport information: (Sudbury, Hadleigh and the Dedham Vale). www.traveline.info or call: 0871 200 22 33 Nayland is located beside the A134 Nayland can be reached by bus or taxi from between Colchester and Sudbury. Colchester Station, which is on the London Nayland Village Hall car park, CO6 4JH Liverpool Street to Norwich main line. (located off Church Lane in Nayland). Train information: www.nationalrail.co.uk or call: 03457 48 49 50 Dedham Vale AONB and Stour Valley Project Email: [email protected] Tel: 01394 445225 Web: www.dedhamvaleandstourvalley.org Walking in nayland Research, text and some photographs by Simon Peachey. Disclaimer: The document reflects the author’s views. The Dedham Vale AONB is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Designed by: Vertas Design & Print Suffolk, December 2017. Design & Print Suffolk, December 2017. Designed by: Vertas The ancient village of Nayland is Discover more of Suffolk’s countryside – walking, cycling and riding leaflets are DISCOVER yours to download for free at Suffolk County Council’s countryside website – surrounded by some of the loveliest www.discoversuffolk.org.uk www.facebook.com/DiscoverSuffolk countryside in the Dedham Vale twitter.com/DiscoverSuffolk port of Sudbury. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71 Student Dissertation How to cite: Moore, Wes (2020). The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71. Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk The Social and Economic Effects of Migration to New Zealand on the people of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk 1853-71 Wes Moore BA (Hons) Modern History (CNAA) A dissertation submitted to The Open University for the degree of MA in History January 2020 Word count: 15,994 Wes Moore MA Dissertation Abstract This dissertation will analyse what happened to the people of Stoke by Nayland as a result of the migration to New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century. Its time parameters – 1853-71 – are the period of the provincial administration control of migration into New Zealand. The key research questions of this study are: Who migrated to New Zealand during this period and how did the migration affect their life chances? What were the social and economic effects of this migration, particularly on the poorer local families? How did these effects compare with other parish assisted migration in eastern England? Stoke by Nayland in 1851 appears to have been a relatively settled farming community dominated by a few wealthy landowners so emigrants were motivated more by the ‘pull’ of the areas they were moving to than by being ‘pushed’ by high levels of unhappiness ‘at home’. -

Babergh District Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Babergh District Council Consultation response from Babergh District Council Babergh District Council (BDC) considered the Local Government Boundary Commission for England’s draft proposals for the warding arrangements in the Babergh District at its meeting on 21 November 2017, and made the following comments and observations: South Eastern Parishes Brantham & Holbrook – It was suggested that Stutton & Holbrook should be joined to form a single member ward and that Brantham & Tattingstone form a second single member ward. This would result in electorates of 2104 and 2661 respectively. It is acknowledged the Brantham & Tattingstone pairing is slightly over the 10% variation threshold from the average electorate however this proposal represents better community linkages. Capel St Mary and East Bergholt – There was general support for single member wards for these areas. Chelmondiston – The Council was keen to ensure that the Boundary Commission uses the correct spelling of Chelmondiston (not Chelmondistan) in its future publications. There were comments from some Councillors that Bentley did not share common links with the other areas included in the proposed Chelmondiston Ward, however there did not appear to be an obvious alternative grouping for Bentley without significant alteration to the scheme for the whole of the South Eastern parishes. Copdock & Washbrook - It would be more appropriate for Great and Little Wenham to either be in a ward with Capel St Mary with which the villages share a vicar and the people go to for shops and doctors etc. Or alternatively with Raydon, Holton St Mary and the other villages in that ward as they border Raydon airfield and share issues concerning Notley Enterprise Park. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Committee Report Description of Development: Outline- Erection of Detached Two-Storey Dwelling with Garage/Carport and Parking/T

Committee Report Item No: 4 Reference: B/17/00023 Case Officer: John Davies Description of Development: Outline- Erection of detached two-storey dwelling with garage/carport and parking/turning area incorporating existing vehicular access from Raydon Road. As amplified by additional information comprising Agricultural Viability Statement, Land valuation, additional demolition quotation and plans 2489/01A and 02A received 25 April 2017. Location: Ceylon House, Raydon Road, Hintlesham, IP8 3QH Parish: Hintlesham Ward: Brook Ward Member/s: Cllr N Ridley and Cllr B Gasper Site Area: 0.27 Conservation Area: Not in Conservation Area Listed Building: Not Listed Received: 05/01/2017 Expiry Date: 31/03/2017 Application Type: Outline Planning Permission Development Type: Minor Dwellings Environmental Impact Assessment: Environmental Assessment Not Required Applicant: Mr and Mrs Murray Agent: Nick Peasland Architectural Services DOCUMENTS SUBMITTED FOR CONSIDERATION The application, plans and documents submitted by the Applicant can be viewed online. Alternatively a copy is available to view at the Mid Suffolk and Babergh District Council Offices. SUMMARY The proposal has been assessed with regard to adopted development plan policies, the National Planning Policy Framework and all other material considerations. The officers recommend approval of this application on the balance of the relevant issues. The proposed dwelling would represent unsustainable development within the countryside contrary to national and local policies. However, in this case the development would include the removal of large, redundant and unsightly glasshouses which is a material consideration and a potential exception to justify the proposed dwelling. PART ONE – REASON FOR REFERENCE TO COMMITTEE The application is referred to committee for the following reason/s: - A Member of the Council has requested that the application is determined by the appropriate Committee and the request has been made in accordance with the Planning Charter or such other protocol / procedure adopted by the Council. -

CHURCH: Dates of Confirmation/Consecration

Court: Women at Court; Royal Household. p.1: Women at Court. Royal Household: p.56: Gentlemen and Grooms of the Privy Chamber; p.59: Gentlemen Ushers. p.60: Cofferer and Controller of the Household. p.61: Privy Purse and Privy Seal: selected payments. p.62: Treasurer of the Chamber: selected payments; p.63: payments, 1582. p.64: Allusions to the Queen’s family: King Henry VIII; Queen Anne Boleyn; King Edward VI; Queen Mary Tudor; Elizabeth prior to her Accession. Royal Household Orders. p.66: 1576 July (I): Remembrance of charges. p.67: 1576 July (II): Reformations to be had for diminishing expenses. p.68: 1577 April: Articles for diminishing expenses. p.69: 1583 Dec 7: Remembrances concerning household causes. p.70: 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Almoners. 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Porters. p.71: 1599: Orders for supplying French wines to the Royal Household. p.72: 1600: Thomas Wilson: ‘The Queen’s Expenses’. p.74: Marriages: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.81: Godchildren: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.92: Deaths: chronological list. p.100: Funerals. Women at Court. Ladies and Gentlewomen of the Bedchamber and the Privy Chamber. Maids of Honour, Mothers of the Maids; also relatives and friends of the Queen not otherwise included, and other women prominent in the reign. Close friends of the Queen: Katherine Astley; Dorothy Broadbelt; Lady Cobham; Anne, Lady Hunsdon; Countess of Huntingdon; Countess of Kildare; Lady Knollys; Lady Leighton; Countess of Lincoln; Lady Norris; Elizabeth and Helena, Marchionesses of Northampton; Countess of Nottingham; Blanche Parry; Katherine, Countess of Pembroke; Mary Radcliffe; Lady Scudamore; Lady Mary Sidney; Lady Stafford; Countess of Sussex; Countess of Warwick. -

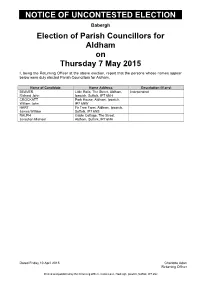

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Aldham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aldham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BEAVER Little Rolls, The Street, Aldham, Independent Richard John Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6NH CROCKATT Park House, Aldham, Ipswich, William John IP7 6NW HART Fir Tree Farm, Aldham, Ipswich, James William Suffolk, IP7 6NS RALPH Gable Cottage, The Street, Jonathan Michael Aldham, Suffolk, IP7 6NH Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Alpheton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alpheton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ARISS Green Apple, Old Bury Road, Alan George Alpheton, Sudbury, CO10 9BT BARRACLOUGH High croft, Old Bury Road, Richard Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BT KEMP Tresco, New Road, Long Melford, Independent Richard Edward Suffolk, CO10 9JY LANKESTER Meadow View Cottage, Bridge Maureen Street, Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BG MASKELL Tye Farm, Alpheton, Sudbury, Graham Ellis Suffolk, CO10 9BL RIX Clapstile Farm, Alpheton, Farmer Trevor William Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BN WATKINS 3 The Glebe, Old Bury Road, Ken Alpheton, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BS Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Assington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Assington. -

Classes and Activities in Long Melford, Lavenham and Surrounding Areas

Classes and activities in Long Melford, Lavenham and surrounding areas Empowering a Resilient Community to Celebrate Being Physically Active Education-Communication-Marketing Physical Activities All the activities in this booklet have been checked and are appropriate for clients but are also just suggestions unless stated as AOR (please see the key below). Classes can also change frequently, so please contact the venue/instructor listed prior to attending. They will also undertake a health questionnaire with you before you start. There are plenty of other classes or activities locally you might want to try. To find out more about the Active Wellbeing Programme or an activity or class near you, please contact your Physical Activity Advisor below: Nick Pringle Physical Activity Advisor – Babergh 07557 64261 [email protected] Key: Contact Price AOR At own risk (to the best of our knowledge, these activities haven’t got one or more of the following – health screen procedure prior to initial attendance, relevant instructor qualifications or insurance therefore if clients attend it is deemed at own risk) Activities in Long Melford and Lavenham Carpet Bowles Please contact AOR We are a friendly club and meet at 9.45am for a 10am start on a Tuesday morning at Lavenham Village Hall to play Carpet Bowls. You do not need to have played before and most people pick it up very quickly, and tuition is available. It is similar to outdoor bowls as you have to try to get your bowl close to the jack (white ball), but it is played indoors on a long carpet. -

Local Wildlife Site Review 2016 Appendix 2 Sites 91-186

APPENDIX 2 Part 2, Sites 91-186 REGISTER OF CHELMSFORD LOCAL WILDLIFE SITES KEY Highlighted LoWS Adjacent Chelmsford LoWS Adjacent LoWS (other local authority) Potential Chelmsford LoWS Sites of Special Scientific Interest ___________________________________________________________________________________ EECOS, April 2016 Chelmsford City Council Local Wildlife Sites Review 2016 Ch91 Fair Wood, Great Leighs (1.27 ha) TL 72931879 Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey® mapping by permission of Ordnance Survey® on behalf of The Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright. Licence number AL 100020327 Fair Wood formerly extended further to the east and south, with a scattering of tall trees denoting its former extent. However, these areas have now lost their woodland character, with the LoWS now being restricted to the remaining core habitat. Within the remaining fragment, Pedunculate Oak (Quercus robur) and Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) coppice dominates over a ground flora comprising Bramble (Rubus fruticosus), Creeping Thistle (Cirsium arvense) and Red Campion (Silene dioica). An old rubbish dump area, formerly excluded from the LoWS has been replanted and is now incorporated into the Site. Ownership and Access The Site is assumed to lie within the ownership of the adjacent horse race track organisation and has no public access. It can be viewed from Moulsham Hall Lane. Habitats of Principal Importance in England Lowland Mixed Deciduous Woodland Selection Criterion HC1 Ancient Woodland Sites ___________________________________________________________________________________ EECOS, April 2016 Chelmsford City Council Local Wildlife Sites Review 2016 Rationale Documentary evidence, along with the structure and flora of the wood, suggest an ancient status for this site. Condition Statement Declining Management Issues Since the last review, this wood has undergone erosion of habitat around its margins, with conversion to a parkland style habitat with oak trees over a grass sward to the south of the entrance security hut. -

Essex Flood Partnership Board

Essex Flood Partnership Board Committee Room 1, Thursday, 26 10:00 County Hall, January 2017 Chelmsford, Essex Membership Cllr Simon Walsh Essex County Council Cllr Mick Page Essex County Council Cllr Kay Twitchen Essex County Council Jon Wilson Essex County Council John Meehan Essex County Council Lucy Shepherd Essex County Council Peter Massie Essex County Council Graham Verrier Environment Agency Rachel Keen Environment Agency Graeme Kasselman. Thames Water Jonathan Glerum Anglian Water Dave Bill Essex County Fire and Rescue Service Cllr Richard Moore Basildon Borough Council Cllr Wendy Schmitt Braintree District Council Cllr Tony Sleep Brentwood Borough Council Cllr Ray Howard Castle Point Borough Council/ECC Cllr Neil Gulliver Chelmsford City Council Cllr Mark Cory Colchester Borough Council Cllr Will Breare-Hall Epping Forest District Council Cllr Danny Purton Harlow District Council Cllr Andrew St Joseph Maldon District Council Cllr Dave Sperring Rochford District Council Cllr Nick Turner Tendring District Council Cllr Martin Terry Southend on Sea Borough Council Cllr Gerrard Rice Thurrock Council Cllr Susan Barker Uttlesford District Council For information about the meeting please ask for: Page 1 of 52 Lisa Siggins 03330134594 / [email protected] Page 2 of 52 Essex County Council and Committees Information This meeting is not open to the public and the press, although the agenda is available on the Essex County Council website, www.essex.gov.uk From the Home Page, click on ‘Your Council’, then on ‘Meetings and Agendas’. Finally, select the relevant committee from the calendar of meetings. Please note that an audio recording may be made of the meeting – at the start of the meeting the Chairman will confirm if all or part of the meeting is being recorded. -

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits Made Under S31(6) Highways Act 1980

Essex County Council (The Commons Registration Authority) Index of Register for Deposits made under s31(6) Highways Act 1980 and s15A(1) Commons Act 2006 For all enquiries about the contents of the Register please contact the: Public Rights of Way and Highway Records Manager email address: [email protected] Telephone No. 0345 603 7631 Highway Highway Commons Declaration Link to Unique Ref OS GRID Statement Statement Deeds Reg No. DISTRICT PARISH LAND DESCRIPTION POST CODES DEPOSITOR/LANDOWNER DEPOSIT DATE Expiry Date SUBMITTED REMARKS No. REFERENCES Deposit Date Deposit Date DEPOSIT (PART B) (PART D) (PART C) >Land to the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops Christopher James Harold Philpot of Stortford TL566209, C/PW To be CM22 6QA, CM22 Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton CA16 Form & 1252 Uttlesford Takeley >Land on the west side of Canfield Road, Takeley, Bishops TL564205, 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated. 6TG, CM22 6ST Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM1 4LN Plan Stortford TL567205 on behalf of Takeley Farming LLP >Land on east side of Station Road, Takeley, Bishops Stortford >Land at Newland Fann, Roxwell, Chelmsford >Boyton Hall Fa1m, Roxwell, CM1 4LN >Mashbury Church, Mashbury TL647127, >Part ofChignal Hall and Brittons Farm, Chignal St James, TL642122, Chelmsford TL640115, >Part of Boyton Hall Faim and Newland Hall Fann, Roxwell TL638110, >Leys House, Boyton Cross, Roxwell, Chelmsford, CM I 4LP TL633100, Christopher James Harold Philpot of >4 Hill Farm Cottages, Bishops Stortford Road, Roxwell, CMI 4LJ TL626098, Roxwell, Boyton Hall Farmhouse, Boyton C/PW To be >10 to 12 (inclusive) Boyton Hall Lane, Roxwell, CM1 4LW TL647107, CM1 4LN, CM1 4LP, CA16 Form & 1251 Chelmsford Mashbury, Cross, Chelmsford, Essex, CM14 11/11/2020 11/11/2020 allocated.