03.AIC 13 Avadanei Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angus Mackay Diaries Volume XVIII (2002 - 2004)

Angus Mackay Diaries Volume XVIII (2002 - 2004) ANGUS MACKAY DIARY NO. 177 Friday February 1 2002 - May 10 2002. Friday February 1 2002 Saturday February 2 2002 To Chiswick this a.m. to shop for K and give him a choice. Got back at twelve, but no sign. Arrived at something after one, animated newsy talk, and an omelette with the blewits and chanterellesI got at the lovely greengrocers - £29.50 a kilo. About two four inch blews and four or five chant. about £3, not bad for such deliciousness. Now it’s Saturday night, and K’s gone, after two wonderful days.I have done nothing except stand up and sit down, and prepare four meals, and I’m exhausted. I fear K might have felt I was lazy or feeble. Well, he started out – ‘Can’t stop here talking, or the light will go’, on the buddleia, ‘which job do you want done first?’ He sawed it right down, and I do see that it’s partly destabilised some bricks. A great relief. I hope that silly fussy man won’t find something else to shout to me about. I was becoming quite reluctant to go into the garden. Horrible to cut anything down, but on balance welcomed it. Comically, the wind was the strongest I’ve heard since I’ve been here. Quite expected a letter of complaint from the next door just as we were cutting down the dangerous bush. They have a ‘patio’ (sic) garden and are clearly nervous of a jungle takeover, or indeed anything they can’t control. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Anatomy of Criticism, Four Essays

ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Four Essays Anatomy or Criticism FOUR ESSAYS ty NORTHROP FRYE PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright 1957, by Princeton University Press All Rights Reserved L.C. Card No. 56-8380 ISBN 0-691-01298-9 (paperback edn.) ISBN 0-691-06004-5 (hardcover edn.) Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, and the Class of 1932 Lectureship. First PRINCETON PAPERBACK Edition, 1971 Third printing, 1973 Tli is book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise disposed of without the pub lisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Printed in the United States of America by Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey HELENAE UXORI PREFATORY STATEMENTS AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS THIS book forced itself on me while I was trying to write some thing else, and it probably still bears the marks of the reluctance with which a great part of it was composed. After completing a of William Blake study (Fearful Symmetry, 1947), I determined to the of apply principles literary symbolism and Biblical typology which I had learned from Blake to another poet, preferably one who had taken these principles from the critical theories of his own day, instead of working them out by himself as Blake did. I therefore a began study of Spenser's Faerie Queene, only to dis cover that in my beginning was my end. The introduction to an Spenser became introduction to the theory of allegory, and that theory obstinately adhered to a much larger theoretical structure. -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A. -

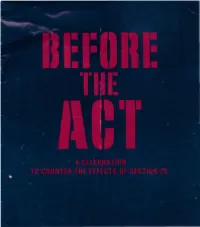

Before-The-Act-Programme.Pdf

Dea F ·e s. Than o · g here tonight and for your Since Clause 14 (later 27, 28 and 29) was an contribution o e Organisation for Lesbian and Gay nounced, OLGA members throughout the country Action (OLGA) in our fight against Section 28 of the have worked non-stop on action against it. We raised Local Govern en Ac . its public profile by organising the first national Stop OLGA is a a · ~ rganisa ·o ic campaigns The Clause Rally in January and by organising and on iss es~ · g lesbians and gay e . e ber- speaking at meetings all over Britain. We have s ;>e o anyone who shares o r cancer , lobbied Lords and MPs repeatedly and prepared a e e eir sexuality, and our cons i u ion en- briefings for them , for councils, for trade unions, for s es a no one political group can take power. journalists and for the general public. Our tiny make C rre ly. apart from our direct work on Section 28, shift office, staffed entirely by volunteers, has been e ave th ree campaigns - on education , on lesbian inundated with calls and letters requ esting informa cus ody and on violence against lesbians and gay ion and help. More recently, we have also begun to men. offer support to groups prematurely penalised by We are a new organisation, formed in 1987 only local authorities only too anxious to implement the days before backbench MPs proposed what was new law. then Clause 14, outlawing 'promotion' of homosexu The money raised by Before The Act will go into ality by local authorities. -

The Company of Strangers: a Natural History of Economic Life

The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life Paul Seabright Contents Page Preface: 2 Part I: Tunnel Vision Chapter 1: Who’s in Charge? 9 Prologue to Part II: 20 Part II: How is Human Cooperation Possible? Chapter 2: Man and the Risks of Nature 22 Chapter 3: Murder, Reciprocity and Trust 34 Chapter 4: Money and human relationships 48 Chapter 5: Honour among Thieves – hoarding and stealing 56 Chapter 6: Professionalism and Fulfilment in Work and War 62 Epilogue to Parts I and II: 71 Prologue to Part III: 74 Part III: Unintended Consequences Chapter 7: The City from Ancient Athens to Modern Manhattan 77 Chapter 8: Water – commodity or social institution? 88 Chapter 9: Prices for Everything? 98 Chapter 10: Families and Firms 110 Chapter 11: Knowledge and Symbolism 126 Chapter 12: Depression and Exclusion 139 Epilogue to Part III: 154 Prologue to Part IV: 155 Part IV: Collective Action Chapter 13: States and Empires 158 Chapter 14: Globalization and Political Action 169 Conclusion: How Fragile is the Great Experiment? 179 The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life Preface The Great Experiment Our everyday life is much stranger than we imagine, and rests on fragile foundations. This is the startling message of the evolutionary history of humankind. Our teeming, industrialised, networked existence is not some gradual and inevitable outcome of human development over millions of years. Instead we owe it to an extraordinary experiment launched a mere ten thousand years ago*. No-one could have predicted this experiment from observing the course of our previous evolution, but it would forever change the character of life on our planet. -

Renaissance Texts, Medieval Subjectivities: Vernacular Genealogies of English Petrarchism from Wyatt to Wroth

Renaissance Texts, Medieval Subjectivities: Vernacular Genealogies of English Petrarchism from Wyatt to Wroth by Danila A. Sokolov A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2012 © Danila A. Sokolov 2012 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation investigates the symbolic presence of medieval forms of textual selfhood in early modern English Petrarchan poetry. Seeking to problematize the notion of Petrarchism as a Ren- aissance discourse par excellence, as a radical departure from the medieval past marking the birth of the modern poetic voice, the thesis undertakes a systematic re-reading of a significant body of early modern English Petrarchan texts through the prism of late medieval English poetry. I argue that me- dieval poetic texts inscribe in the vernacular literary imaginary (i.e. a repository of discursive forms and identities available to early modern writers through antecedent and contemporaneous literary ut- terances) a network of recognizable and iterable discursive structures and associated subject posi- tions; and that various linguistic and ideological traces of these medieval discourses and selves can be discovered in early modern English Petrarchism. Methodologically, the dissertation’s engagement with poetic texts across the lines of periodization is at once genealogical and hermeneutic. The prin- cipal objective of the dissertation is to uncover a vernacular history behind the subjects of early mod- ern English Petrarchan poems and sonnet sequences. -

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 the OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The Oxfordian is the peer-reviewed journal of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, a non-profit educational organization that conducts research and publication on the Early Modern period, William Shakespeare and the authorship of Shakespeare’s works. Founded in 1998, the journal offers research articles, essays and book reviews by academicians and independent scholars, and is published annually during the autumn. Writers interested in being published in The Oxfordian should review our publication guidelines at the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship website: https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/the-oxfordian/ Our postal mailing address is: The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship PO Box 66083 Auburndale, MA 02466 USA Queries may be directed to the editor, Gary Goldstein, at [email protected] Back issues of The Oxfordian may be obtained by writing to: [email protected] 2 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 Acknowledgements Editorial Board Justin Borrow Ramon Jiménez Don Rubin James Boyd Vanessa Lops Richard Waugaman Charles Boynton Robert Meyers Bryan Wildenthal Lucinda S. Foulke Christopher Pannell Wally Hurst Tom Regnier Editor: Gary Goldstein Proofreading: James Boyd, Charles Boynton, Vanessa Lops, Alex McNeil and Tom Regnier. Graphics Design & Image Production: Lucinda S. Foulke Permission Acknowledgements Illustrations used in this issue are in the public domain, unless otherwise noted. The article by Gary Goldstein was first published by the online journal Critical Stages (critical-stages.org) as part of a special issue on the Shakespeare authorship question in Winter 2018 (CS 18), edited by Don Rubin. It is reprinted in The Oxfordian with the permission of Critical Stages Journal. -

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: • Howard-Field Casting, (Los Angeles, London & Europe) 1993-2014 • Director of Feature Casting, Warner Bros. Studios, Los Angeles 1989-1993 • Howard-Field Casting ( London & Europe) 1983-1989 • Casting & Project Consultant RKO, London operations 1983-1985 • Associate Casting Director Royal Shakespeare Company, London 1977-1983 • Production Assistant to director/producer Martin Campbell, London 1975-1977 • Assistant to writer, Tudor Gates, Drumbeat Productions, London 1975-1977 FILMS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT FOR 2014/15: AMOK – Director: Kasia Adamik. Screenplay: Richard Karpala. Executive producer: Agnieszka Holland. Producers: Beata Pisula, Debbie Stasson - in development for spring 2015 WALKING TO PARIS – Director: Peter Greenaway, Producer: Kees Kasander and Julia Ton. Scheduled to commence pp February 2015 in Romania, Switzerland and France. THE WORLD AT NIGHT – Director: TBC. Screenplay: William Nicholson. Producer: Vanessa van Zuylen, (VVZ Presse, Paris, France), Matthias Ehrenberg, Jose Levy, (Cuatro Films Plus) Ibon Cormenzana, (Arcadia Motion Pictures), – in development to shoot Argentina and France Spring 2015. Daniel Bruhl attached. RACE – In association with Suzanne Smith Casting. Director: Stephen Hopkins. Filming Berlin and Canada, September 2014. Casting a selection of cameo roles from the UK AMERICAN MASSACRE – Director: TBC Producer: Emjay Rechsteiner (Staccato Films); Executive Producer: Harris Tulchin - in development for Spring 2015, shooting New Zealand and Canary Islands LITTLE SECRET (Pequeno Segredo) – Director: David Schurmann; Writer: Marcos Bernstein; Producers: Matthias Ehrenberg (Cuatro Films Plus), Joao, Roni (Ocean Films, Brazil), Emma Slade (Fire Fly Films, NZ), Barrie Osborn – in development to shoot Brazil, October 2014. Finnoula Flanagan attached THE BAY OF SILENCE: - Director: Mark Pellington; Screenwriter & Producer: Caroline Goodall, Executive Producer: Peter Garde. -

Original Writer Title Genre Running Time Year Director/Writer Actor

Original Running Title Genre Year Director/Writer Actor/Actress Keywords Writer Time Katharine Hepburn, Alcoholism, Drama, Tony Richardson; Edward Albee A Delicate Balance 133 min 1973 Paul Scofield, Loss, Play Edward Albee Lee Remick Family Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. I Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 54 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. II Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. III Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 53 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. IV Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 50 min 1995 Austen, Andrew Crispin Bonham-Carter, Vol. V Romance Classic, Davies Jennifer Ehle Strong Female Lead, Inheritance Georgian, Eighteenth Century, Simon Langton; Jane Colin Firth, Pride and Prejudice Drama, Romance, Jane Austen 52 min 1995 Austen, -

Time, Death, and Mutability : a Study of Themes in Some Poetry of The

TIME, DEATH, and MUTABILITY: A Study of Themes in Some Poetry of the Renaissance - Spenser, Shakespeare, and Donne Jean Miriam Gerber B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 1961 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFUHE3T OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English Jean Miriam Gerber, 1968 Simon Fraser University J~Y,1968 EXA XINIMG COK4ITTEX APPROVAL (name) Senior Supervisor \ ( name) Examining Cormittoe " - ( name ) Examining Conunittee PARTTAL COPYRIGIIT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Sttldies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/~issertation: Author: (signature ) (name ) (date) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank Mr. Clark Cook for his many suggestions and close attention. Special thanks are also due to Mr. James Sandison who read this study in manuscript. Above all I wish to thank Dr. F. B. Candelaria, who supervised the thesis. ABSTRACT This study was undertaken in order to exanine some examples of Renaissance poe+zy in the light of the themes of love, death, time, and mutability. -

Anatomy of Criticism with a New Foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY of CRITICISM

Anatomy of Criticism With a new foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Four Essays Anatomy of Criticism FOUR ESSAYS With a Foreword by Harold Bloom NORTHROP FRYE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY Copyright © 1957, by Princeton University Press All Rights Reserved L.C. Card No. 56-8380 ISBN 0-691-06999-9 (paperback edn.) ISBN 0-691-06004-5 (hardcover edn.) Fifteenth printing, with a new Foreword, 2000 Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, and the Class of 1932 Lectureship. FIRST PRINCETON PAPERBACK Edition, 1971 Third printing, 1973 Tenth printing, 1990 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) {Permanence of Paper) www.pup.princeton.edu 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 Printed in the United States of America HELENAE UXORI Foreword NORTHROP FRYE IN RETROSPECT The publication of Northrop Frye's Notebooks troubled some of his old admirers, myself included. One unfortunate passage gave us Frye's affirmation that he alone, of all modern critics, possessed genius. I think of Kenneth Burke and of William Empson; were they less gifted than Frye? Or were George Wilson Knight or Ernst Robert Curtius less original and creative than the Canadian master? And yet I share Frye's sympathy for what our current "cultural" polemicists dismiss as the "romantic ideology of genius." In that supposed ideology, there is a transcendental realm, but we are alienated from it.