Between the “Facts and Norms” of Police Violence: Using Discourse Models to Improve Deliberations Around Law Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

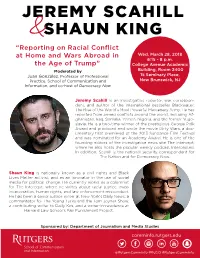

Jeremy Scahill Shaun King

JEREMY SCAHILL &SHAUN KING “Reporting on Racial Conflict at Home and Wars Abroad in Wed, March 28, 2018 6:15 - 8 p.m. the Age of Trump” College Avenue Academic Moderated by Building, Room 2400 Juan González, Professor of Professional 15 Seminary Place, Practice, School of Communication and New Brunswick, NJ Information, and co-host of Democracy Now Jeremy Scahill is an investigative reporter, war correspon- dent, and author of the international bestseller Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army. He has reported from armed conflicts around the world, including Af- ghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Yemen, Nigeria, and the former Yugo- slavia. He is a two-time winner of the prestigious George Polk Award and produced and wrote the movie Dirty Wars, a doc- umentary that premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award. He is one of the founding editors of the investigative news site The Intercept, where he also hosts the popular weekly podcast Intercepted. In addition, Scahill is the national security correspondent for The Nation and for Democracy Now. Shaun King is nationally known as a civil rights and Black Lives Matter activist, and as an innovator in the use of social media for political change. He currently works as a columnist for The Intercept, where he writes about racial justice, mass incarceration, human rights, and law enforcement misconduct. He has been a senior justice writer at New York’s Daily News, a commentator for The Young Turks and the Tom Joyner Show, a contributing writer to Daily Kos, and a writer-in-residence at Harvard Law School’s Fair Punishment Project. -

Stay Woke, Give Back Virtual Tour Day of Empowerment Featuring Justin Michael Williams

11 1 STAY WOKE, GIVE BACK VIRTUAL TOUR DAY OF EMPOWERMENT FEATURING JUSTIN MICHAEL WILLIAMS On the STAY WOKE, GIVE BACK TOUR, Justin empowers students to take charge of their lives, and their physical and mental wellbeing with mass meditation events at high schools, colleges, and cultural centers across the country. The tour began LIVE in-person in 2020, but now with the Covid crisis—and students and teachers dealing with the stressors of distance learning—we’ve taken the tour virtual, with mass Virtual Assemblies to engage, enliven, and inspire students when they need us most. From growing up with gunshot holes outside of his bedroom window, to sharing the stage with Deepak Chopra, Justin Michael Williams knows the power of healing to overcome. Justin Michael Williams More: StayWokeGiveBack.org Justin is an author, top 20 recording artist, and transformational speaker whose work has been featured by The Wall Street Journal, Grammy.com, Yoga Journal, Billboard, Wanderlust, and South by Southwest. With over a decade of teaching experience, Justin has become a pioneering millennial voice for diversity and inclusion in wellness. What is the Stay Woke Give Back Tour? Even before the start of Covid-19, anxiety and emotional unrest have been plaguing our youth, with suicide rates at an all-time high. Our mission is to disrupt that pattern. We strive to be a part of the solution before the problem starts—and even prevent it from starting in the first place. Instead of going on a traditional “book tour,” Justin is on a “GIVE BACK” tour. At these dynamic Virtual Assemblies—think TED talk meets a music concert—students will receive: • EVENT: private, school-wide Virtual Assembly for entire staff and student body (all tech setup covered by Sounds True Foundation) • LONG-TERM SUPPORT: free access to a 40-day guided audio meditation program, delivered directly to students daily via SMS message every morning, requiring no staff or administrative support. -

Factors Leading to Civil Unrest in the Wake of Police Lethal Use of Force Incidents

CALIFORNIA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY Riverside, California Factors Leading to Civil Unrest in the Wake of Police Lethal Use of Force Incidents: A Tale of Two Cities A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Public Administration George Richard Austin, Jr. Division of Online and Professional Studies Department of Public Administration April 2019 Factors Leading to Civil Unrest in the Wake of Police Lethal Use of Force Incidents: A Tale of Two Cities Copyright © 2019 by George Richard Austin, Jr. ii ABSTRACT Factors Leading to Civil Unrest in the Wake of Police Lethal Use of Force Incidents: A Tale of Two Cities by George Richard Austin, Jr. Since August 9, 2014, the day Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in the small city of Ferguson, Missouri, large-scale protests after police-involved lethal use of force incidents have become much more prevalent. While there is much academic and public debate on why civil unrest occurs after these unfortunate incidents, there is very little scholarly literature that explores the structure of civil unrest events or literature that attempts to explain why and how peaceful protests turn violent. This dissertation, through exploratory content analysis of extensive after-action reports, provides insight into two instances of civil unrest in the wake of officer-involved lethal use of force incidents: the Minneapolis, Minnesota, civil unrest in the aftermath of the November 15, 2015 shooting of Jamar Clark and the Charlotte, North Carolina, civil unrest in the wake of the September 16, 2016, shooting of Keith Lamont Scott. The study examines the phenomenon of civil unrest from the theoretical frameworks of representative bureaucracy and rational crime theory and utilizes a case study comparison and content analysis research design. -

Yanti | 39 WORKS CITED Abrams, M. H. a Glossary of Literary Terms

Y a n t i | 39 WORKS CITED Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 9th ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009. Barker, Chris. Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice. 3rd Ed. London: SAGE Publication. 2008. Blank, Rebecca M, Marilyn Dabady, and Constance F. Citro. Measuring Racial Discrimination. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004. Print. Bobo, L. D & Fox Cybelle. Race, Racism, and Discrimination: Bridging Problems and Theory in Social Psychological Research. Social Psychology Quarterly. Vol. 66 (4): 319-332. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1388607. Criss, Doug, and Ford, Dana. “Black Lives Matter Activist Shaun King Addresses Race Reports” CNN, Retrieved on August 21, 2015, https://edition.cnn.com/2015/08/20/us/shaun-king-controversy/index.html Dewi, Kartika Risma, and Indriani, Martha. Analysis of Racial Discrimination Towards Uncle Tom in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. AESTHETIC, Vol. 8, No.2, Retrieved on 2019. Feagin, Joe, and Vera, Hernan. White Racism: The Basics. New York: Routledge. 1995. Feagin, Joe. R. Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. New York: Routledge, 2006. Feagin, Joe. R. Racist America: Roots, Current Realities, and Future Reparations. New York: Routledge. 2000. Henry, F. & Tator, C. The Color of Democracy: Racism in Canadian society (3rd Y a n t i | 40 Edition). Toronto, ONT: Thomson Nelson, Canada. 2006. Hill, Evan et al. "How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody." The New York Times, Retrieved May 31, 2020, https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/george-fl oyd-investigation.amp.html. Hirsch, Afua. "Angie Thomas: the debut novelist who turned racism and police violence into a bestseller. -

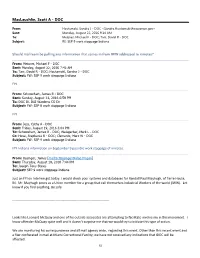

Maclauchlin, Scott a - DOC

MacLauchlin, Scott A - DOC From: Hautamaki, Sandra J - DOC <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, August 22, 2016 9:14 AM To: Meisner, Michael F - DOC; Tarr, David R - DOC Subject: RE: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana Should mailroom be pulling any information that comes in from IWW addressed to inmates? From: Meisner, Michael F - DOC Sent: Monday, August 22, 2016 7:42 AM To: Tarr, David R - DOC; Hautamaki, Sandra J - DOC Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI From: Schwochert, James R - DOC Sent: Sunday, August 21, 2016 6:59 PM To: DOC DL DAI Wardens CO Dir Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI From: Jess, Cathy A - DOC Sent: Friday, August 19, 2016 3:04 PM To: Schwochert, James R - DOC; Weisgerber, Mark L - DOC Cc: Hove, Stephanie R - DOC; Clements, Marc W - DOC Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI Indiana information on September 9 possible work stoppage of inmates. From: Basinger, James [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, August 18, 2016 7:44 PM To: Joseph Tony Stines Subject: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana Just an FYI on Intel we got today. I would check your systems and databases for Randall Paul Mayhugh, of Terre Haute, IN. Mr. Mayhugh poses as a Union member for a group that call themselves Industrial Workers of the world (IWW). Let know if you find anything. Be safe ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Looks like Leonard McQuay and one of his outside associates are attempting to facilitate involve my in this movement. I know offender McQuay quite well and it doesn't surprise me that we would try to initiate this type of action. -

Maintaining First Amendment Rights and Public Safety in North Minneapolis: an After-Action Assessment of the Police Response To

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE OFFICE OF COMMUNITY ORIENTED POLICING SERVICES CRITICAL RESPONSE INITIATIVE MAINTAINING FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS AND PUBLIC SAFETY IN NORTH MINNEAPOLIS An After-Action Assessment of the Police Response to Protests, Demonstrations, and Occupation of the Minneapolis Police Department’s Fourth Precinct Frank Straub | Hassan Aden | Jeffrey Brown | Ben Gorban | Rodney Monroe | Jennifer Zeunik This project was supported by grant number 2015-CK-WX-K005 awarded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. References to specific agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement by the author(s) or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. The Internet references cited in this publication were valid as of the date of publication. Given that URLs and websites are in constant flux, neither the author(s) nor the COPS Office can vouch for their current validity. Recommended citation: Straub, Frank, Hassan Aden, Jeffrey Brown, Ben Gorban, Rodney Monroe, and Jennifer Zeunik. 2017. Maintaining First Amendment Rights and Public Safety in North Minneapolis: An After-Action Assessment of the Police Response to Protests, Demonstrations, and Occupation of the Minneapolis Police Department’s Fourth Precinct. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Published 2017 CONTENTS Letter from the Director . .vi Executive Summary . vii Summary of events vii Implications and challenges vii Public safety response vii Key themes of the review viii Conclusion ix Part I . -

DEEN FREELON CHARLTON D. MCILWAIN MEREDITH D. CLARK About the Authors: Deen Freelon Is an Assistant Professor of Communication at American University

BEYOND THE HASHTAGS DEEN FREELON CHARLTON D. MCILWAIN MEREDITH D. CLARK About the authors: Deen Freelon is an assistant professor of communication at American University. Charlton D. McIlwain is an associate professor of media, culture and communi- cation and Associate Dean for Faculty Development and Diversity at New York University. Meredith D. Clark is an assistant professor of digital and print news at the University of North Texas. Please send any questions or comments about this report to Deen Freelon at [email protected]. About the Center For Media & Social Impact: The Center for Media & Social Impact at American University’s School of Communication, based in Washington, D.C., is an innovation lab and research center that creates, studies, and showcases media for social impact. Fo- cusing on independent, documentary, entertainment and public media, the Center bridges boundaries between scholars, producers and communication practitioners across media production, media impact, public policy, and audience engagement. The Center produces resources for the field and academic research; convenes conferences and events; and works collaboratively to understand and design media that matters. www.cmsimpact.org Internal photos: Philip Montgomery Graphic design and layout: openbox9 The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Spencer Foundation, without which this project would not have been possible. We also thank Ryan Blocher, Frank Franco, Cate Jackson, and Sedale McCall for transcribing participant interviews; David Proper and Kate Sheppard for copyediting; and Mitra Arthur, Caty Borum Chattoo, Brigid Maher, and Vincent Terlizzi for assisting with the report’s web presence and PR. The views expressed in this report are the authors’ alone and are not necessarily shared by the Spencer Foundation or the Center for Media and Social Impact. -

Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era Maria Hamming Grand Valley State University

McNair Scholars Journal Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 4 2017 Counting Color: Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era Maria Hamming Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Hamming, Maria (2017) "Counting Color: Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol21/iss1/4 Copyright © 2017 by the authors. McNair Scholars Journal is reproduced electronically by ScholarWorks@GVSU. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ mcnair?utm_source=scholarworks.gvsu.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol21%2Fiss1%2F4&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages Counting Color: Biracial Activism in the Black Lives Matter Era Introduction and was pregnant. Nixon knew that Colvin would be a “political liability in certain On March 2, 1955 Claudette Colvin parts of the black community”6 and would would find a seat on a city bus in certainly fuel stereotypes from the White Montgomery, Alabama and send the community.7 Montgomery bus boycott into motion. A 10th grader at Booker T. Washington Colorism explains why Claudette High School, Claudette felt empowered Colvin was not used as the face of the by her class history lessons on Harriet Montgomery bus boycott. Color classism, Tubman and Sojourner Truth, and was or colorism, is defined as “a social, disillusioned by the “bleak racial conditions economic, and political societal framework in Montgomery.”1 Per the segregation laws that follows skin-color differences, such at the time, Claudette sat in the rear of the as those along a continuum of possible bus, which was designated for “colored” shades, those with the lightest skin color passengers. -

“Progressive” Prosecutors Sabotage the Rule of Law, Raise Crime Rates, and Ignore Victims Charles D

LEGAL MEMORANDUM No. 275 | OCTOBER 29, 2020 EDWIN MEESE III CENTER FOR LEGAL & JUDICIAL STUDIES “Progressive” Prosecutors Sabotage the Rule of Law, Raise Crime Rates, and Ignore Victims Charles D. Stimson and Zack Smith Introduction KEY TAKEAWAYS The American prosecutor occupies a unique role Rogue prosecutors usurp the role of state among lawyers. The prosecutor has a higher duty legislatures, thereby violating the sepa- than other attorneys. His duty is to seek justice, not ration of powers between the executive branch and legislative branch. simply to obtain convictions. As the American Bar Association notes, “The prosecutor should seek to protect the innocent and convict the guilty, consider Rogue prosecutors abuse the role of the the interests of victims and witnesses, and respect the district attorney by refusing to prosecute constitutional and legal rights of all persons, including broad categories of crimes, thereby failing suspects and defendants.”1 to enforce the law faithfully. Prosecutors play a vital and indispensable role in the fair and just administration of criminal law. As mem- bers of the executive branch at the local, state, or federal Violent crime goes up and victims’ rights level, they, like all other members of the executive are ignored in rogue prosecutors’ cities. branch, take an oath to support and defend the Consti- tution and faithfully execute the law as written. They do not make laws. That is the duty of the legislative branch. This paper, in its entirety, can be found at http://report.heritage.org/lm275 The Heritage Foundation | 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. -

Blue Lives Matter

COP FRAGILITY AND BLUE LIVES MATTER Frank Rudy Cooper* There is a new police criticism. Numerous high-profile police killings of unarmed blacks between 2012–2016 sparked the movements that came to be known as Black Lives Matter, #SayHerName, and so on. That criticism merges race-based activism with intersectional concerns about violence against women, including trans women. There is also a new police resistance to criticism. It fits within the tradition of the “Blue Wall of Silence,” but also includes a new pro-police movement known as Blue Lives Matter. The Blue Lives Matter movement makes the dubious claim that there is a war on police and counter attacks by calling for making assaults on police hate crimes akin to those address- ing attacks on historically oppressed groups. Legal scholarship has not comprehensively considered the impact of the new police criticism on the police. It is especially remiss in attending to the implications of Blue Lives Matter as police resistance to criticism. This Article is the first to do so. This Article illuminates a heretofore unrecognized source of police resistance to criticism by utilizing diversity trainer and New York Times best-selling author Robin DiAngelo’s recent theory of white fragility. “White fragility” captures many whites’ reluctance to discuss ongoing rac- ism, or even that whiteness creates a distinct set of experiences and per- spectives. White fragility is based on two myths: the ideas that one could be an unraced and purely neutral individual—false objectivity—and that only evil people perpetuate racial subordination—bad intent theory. Cop fragility is an analogous oversensitivity to criticism that blocks necessary conversations about race and policing. -

Police Violence Against Afro-Descendants in the United States

Cover Art Concept This IACHR report concludes that the United States has systematically failed to adopt preventive measures and to train its police forces to perform their duties in an appropriate fashion. This has led to the frequent use of force based on racial bias and prejudice and tends to result in unjustified killings of African Americans. This systematic failure is represented on the cover of the report by a tombstone in the bullseye of a shooting range target, which evokes the path of police violence from training through to these tragic outcomes. The target is surrounded by hands: hands in the air trying to stop the bullet, hands asking for help because of the danger that police officers represent in certain situations, and hands expressing suffering and pain over the unjustified loss of human lives. Cover design: Pigmalión / IACHR OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 156 26 November 2018 Original: English INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS African Americans, Police Use of Force, and Human Rights in the United States 2018 iachr.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. African Americans, police use of force, and human rights in the United States : Approved by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on November 26, 2018. p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978-0-8270-6823-0 1. Human rights. 2. Police misconduct--United States. 3. Race discrimination-- United States. 4. African Americans--Civil rights. 5. Racism--United States. I. Title. II. Series. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.156/18 INTER-AMERICAN -

United States District Court District of Minnesota

CASE 0:20-cv-01645 Document 1 Filed 07/28/20 Page 1 of 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MINNESOTA Nekima Levy Armstrong, Marques Armstrong, Terry Hempfling, and Rachel Clark, On behalf of themselves and other similarly situated individuals, Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action No. ______________ City of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Chief of Police JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Medaria Arradondo in his individual and official capacity; Minneapolis Police Lieutenant Robert Kroll, in his individual and official capacity; COMPLAINT Minnesota Department of Public Safety Commissioner John Harrington, in his individual and official capacity; Minnesota State Patrol Colonel Matthew Langer, in his individual and official capacity; and John Does 1-2, in their individual and official capacities, Defendants. For their Complaint, Plaintiffs state and allege as follows: INTRODUCTION The right to assemble is fundamental, as is the right to speak out against injustice. These rights are enshrined in our Constitution. Ideas and movements that changed the course of our history came to the forefront of the American consciousness through assembly and protest. Law enforcement too often has been on the wrong side of history, attempting to suppress the right of the people to assemble. This freedom cannot be suppressed and it must be protected at all costs. Minnesota is no exception. Historically, law enforcement in Minneapolis specifically, and Minnesota more generally, have attempted to suppress the right of its citizens to assemble peacefully. Recently, they have been and are actively suppressing this right by exercising CASE 0:20-cv-01645 Document 1 Filed 07/28/20 Page 2 of 32 unnecessary and excessive force against protesters who gathered to express their outrage at the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department.