BIODIVERSITY and PROTECTED AREAS Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affect Forest and Wildlife?

HowHow WouldWould AffectAffect ForestForest andand Wildlife?Wildlife? 2 © W. Phumanee/ WWF-Thailand Introduction Mae Wong National Park is part of Thailand’s Western Forest Complex: the largest contiguous tract of forest in all of Thailand and Southeast Asia. Mae Wong National Park has been a conservation area for almost 30 years, and today the area is regarded internationally as a place that can offer a safe habitat and a home to many diverse species of wildlife. The success of Mae Wong National Park is the result of many years and a great deal of effort invested in conserving and protecting the Mae Wong forest, as well as ensuring its symbiosis with surrounding areas such as the Tung Yai Naresuan - Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991. The large-scale conservation of these areas has enabled the local wildlife to have complete freedom within an extensive tract of forest, and to travel unimpeded in and around its natural habitat. However, even as Mae Wong National Park retains its status as a protected area, it stills faces persistent threats to its long-term sustainability. For many years, certain groups have attempted to forge ahead with large- scale construction projects within the National Park, such as the Mae Wong Dam. For the past 30 years, government officials have been pressured into authorizing the dam’s construction within the conservation area, despite the fact that the project has never passed an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). It is clear, then, that if the Mae Wong Dam project should go ahead, it will have a tremendously destructive impact on the park’s ecological diversity, and will bring about the collapse of the forest’s natural ecosystem. -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 06:11:13PM Via Free Access

Tijdschrift voor Entomologie 160 (2017) 89–138 An initial survey of aquatic and semi-aquatic Heteroptera (Insecta) from the Cardamom Mountains and adjacent uplands of southwestern Cambodia, with descriptions of four new species Dan A. Polhemus Previous collections of aquatic Heteroptera from Cambodia have been limited, and the biota of the country has remained essentially undocumented until the past several years. Recent surveys of aquatic Heteroptera in the Cardamom Mountains and adjacent Kirirom and Bokor plateaus of southwestern Cambodia, coupled with previous literature records, demonstrate that 11 families, 35 genera, and 68 species of water bugs occur in this area. These collections include 13 genus records and 37 species records newly listed for the country of Cambodia. The following four new species are described based on these recent surveys: Amemboa cambodiana n. sp. (Gerridae); Microvelia penglyi n. sp., Microvelia setifera n. sp. and Microvelia bokor n. sp. (all Veliidae). Based on an updated checklist provided herein, the aquatic Heteroptera biota of Cambodia as currently known consists of 78 species, and has an endemism rate of 7.7%, although these numbers should be considered provisional pending further sampling. Keywords: Heteroptera; Cambodia; water bugs; new species; new records Dan A. Polhemus, Department of Natural Sciences, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, HI 96817 USA. [email protected] Introduction of collections or species records from the country in Aquatic and semi-aquatic Heteroptera, commonly the period preceding World War II. Following that known as water bugs, are a group of worldwide dis- war, the country’s traumatic social and political his- tribution with a well-developed base of taxonomy. -

Mr. Cholathorn Chamnankid

Thailand ASEAN Heritage Parks Mr. Cholathorn Chamnankid Director of National Parks Research and Innovation Development Division National Parks office, DNP ⚫PAs Of TH ⚫AHP in TH ⚫ Khao Yai NP (1984) No. 10 ⚫ Tarutao NP (1984) No. 11 ⚫ Mo Ko Surin-Mo Ko Similan-Ao Phang-nga NP Complex (2003) No. 22 ⚫ Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex (2003) No. 23 ⚫AHP in TH 2019 Content ⚫ Hat Chao Mai NP and Mo Ko Libong Non-hunting Area (2019) No. 45 ⚫ Mu Koh Ang Thong NP (2019) No. 46 ⚫AHP Country Reports ⚫Purpose in TH (2020-2025) Protected Area of Thailand สาธารณรัฐประชาธิปไตยประชาชนลาว 1. Pai Watershed – Salawin Forest14 . Khlong Saeng-khao Sok Complex Forest Complex 2. Sri Lanna - Khun Tan Forest 15. Khao Luang Forest Complex เมยี นมาร์ Complex 16. Khao Banthat Forest 3. Doi Phu Kha - Mae Yom Forest Complex Complex กัมพูชา 17. Hala Bala Forest ประชาธิปไตย 4. Mae Ping – Om Goi Forest Complex Complex 18. Mu Ko Similan –Phi Phi - Andaman อา่ วไทย 5. Phu Miang - Phu Thong Forest Complex 19. Mu Ko Ang Thong-gulf of Thailand 6. Phu Khiao – Nam Nao Forest 7. Phu Phan Forest Complex 8. Phanom Dong Rak-pha Taem Forest Complex อุทยานแห่งชาติ 9. Dong Phayayen Khao Yai Forest มาเลเซีย เขตรกั ษาพนั ธุส์ ัตวป์ ่า Complex 10. Eastern Forest Complex PAs TH Category No. Area % of country (sq km) area National Park 133 63,532.49 12.38 Forest Park 94 1,164 0.22 Wildlife Sanctuary 60 37377.12 7.2 Non-hunting Area 80 5,736.36 1.11 Botanical Garden 16 49.44 0.009 Arboretum 55 40.67 0.007 Biosphere Reserve 4 216 0.05 Proposed PAs 22 6402.24 1.25 Total 114,518.32 22.26 Thailand and International Protected Areas Conservation Mechanisms Year ratified Convention Remarks CITES 1983 WHC 1987 2 Natural & 3 Cultural WH sites RAMSAR 1998 14 internationally recognized wetlands CBD 2003 UNFCCC 1995 AHP 1984 Khao Yai NP, Tarutao MNP, Kaeng Kracharn Forest Complex, Surin & Similan MNPs, Ao Phangnga Complex, Hat Chao Mai - Mu Koh Libong, Mu Ko Ang Thong Marine National Park ▪AHP in TH 1. -

Non-Panthera Cats in South-East Asia Tantipisanuh Et Al

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 8 | SPRING 2014 Non-CATPanthera cats in newsSouth-east Asia 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guest Editors: J. W. Duckworth Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Antony Lynam This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Cover Photo: Non-Panthera cats of South-east Asia: from the Taiwan Council of Agriculture’s Forestry Bureau, Zoo Leipzig and From top centre clock-wise the Wild Cat Club. jungle cat (Photo K. Shekhar) clouded leopard (WCS Thailand Prg) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh fishing cat (P. Cutter) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser, Jonas Bach leopard cat (WCS Malaysia Prg) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Asiatic golden cat (WCS Malaysia Prg) marbled cat (K. Jenks) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

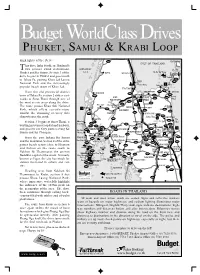

Phuket &Krabi Loop

Budget WorldClass Drives PHUKET, SAMUI & KRABI LOOP Highlights of the Drive 4006 KO PHANGAN G U L F O F T H A I L A N D his drive links Southern Thailand’s T two premier island destinations, A N D A M A N Ban Chaweng Mu Ko Ang Thong Phuket and Ko Samui. Section 1 of the S E A KAPOE THA CHANA KO SAMUI drive begins in Phuket and goes north Ban Nathon to Takua Pa, passing Khao Lak Lamru 4169 CHAIYA 4170 National Park and the increasingly Phum Riang 4 Ferry popular beach resort of Khao Lak. DON SAK THA CHANG 4142 From the old provincial district KANCHANADIT 4142 KHANOM KURA BURI 41 PHUNPHIN 4232 town of Takua Pa, section 2 strikes east- 4 401 4014 Hat Nai KHIRI SURAT 4010 wards to Surat Thani through one of RATTANIKHOM THANI Phlao 401 3 the most scenic areas along the drive. 4134 4100 Khao Sok Rachaphrapha 41 The route passes Khao Sok National KHIAN SA SICHON TAKUA PA Dam SAN NA DOEM 2 401 4106 Park, which offers eco-adventure BAN TAKHUN 4009 401 4133 amidst the stunning scenery that 4032 PHANOM BAN NA SAN 4188 4186 characterises the park. Krung Ching NOPPHITAM KAPONG 415 4140 THA Khao Lak WIANG SA (roads closed) SALA Section 3 begins at Surat Thani, a 4090 Lam Ru 4035 PHRA PHIPUN 4141 bustling provincial capital and harbour, 4240 4090 PHLAI PHRAYA 4016 4 4197 SAENG PHROMKHIRI 4013 4133 4015 5 and goes to car-ferry ports serving Ko 4 PHANG NGA 4035 CHAI BURI NAKHON SRI Hat Thai THAP PHUT 4228 Khao Samui and Ko Phangan. -

Hua Hin Beach

Cover_m14.indd 1 3/4/20 21:16 Hua Hin Beach 2-43_m14.indd 2 3/24/20 11:28 CONTENTS HUA HIN 8 City Attractions 9 Activities 15 How to Get There 16 Special Event 16 PRACHUAP KHIRI KHAN 18 City Attractions 19 Out-Of-City Attractions 19 Local Products 23 How to Get There 23 CHA-AM 24 Attractions 25 How to Get There 25 PHETCHABURI 28 City Attractions 29 Out-Of-City Attractions 32 Special Events 34 Local Products 35 How to Get There 35 RATCHABURI 36 City Attractions 37 Out-Of-City Attractions 37 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 2-43_m14.indd 3 3/24/20 11:28 HUA HIN & CHA-AM HUA HIN & CHA-AM Prachuap Khiri Khan Phetchaburi Ratchaburi 2-43_m14.indd 4 3/24/20 11:28 2-43_m14.indd 5 3/24/20 11:28 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Kingdom of Cambodia 2-43_m14.indd 6 3/24/20 11:28 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Kingdom of Cambodia 2-43_m14.indd 7 3/24/20 11:28 Hat Hua Hin HUA HIN 2-43_m14.indd 8 3/24/20 11:28 Hua Hin is one of Thailand’s most popular sea- runs from a rocky headland which separates side resorts among overseas visitors as well as from a tiny shing pier, and gently curves for Thais. Hua Hin, is located 281 kiometres south some three kilometres to the south where the of Bangkok or around three-hour for driving a Giant Standing Buddha Sculpture is located at car to go there. -

Arana John.Pdf

48056307: MAJOR: ARCIIlTECTURAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT AND TOURISM KEYWORD: SITE DIAGNOSTIC, NATURAL HERITAGE, KHAO YA!, DONG PHAY A YEN KHAO Y Al FOREST COMPLEX. JOHN ARANA: SITE DIAGNOSTIC AND VISITOR FACILITIES IMPROVEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS, AT THE KHAO YA! NATIONAL PARK. RESEARCH PROJECT ADVISOR: ASST.PROF. DEN WASIKSIRI, 143 pp. Khao Yai is Thailand's first and best known national park. It contains a wealth of natural attractions: Flora, Fauna, Vistas and waterfalls. The park was established in 1962 and is currently managed by National Parle, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department. Khao Yai has been declared a world heritage site as part of the Dong Phayayen Khao Yai Forest Complex under criterion (IV) in 2005 and was also previously declared an Association of South East Asian Nation (ASEAN) heritage pad. in I 984. This research project attempts to increase understanding of the park, raise awareness regarding the condition of park tourism infrastructure and assist in future decision making process by providing a visitor's perspective. The most recent management plan for Khao Yai National Park 2007-2017 has not been received with enthusiasm. In this study the author encourages the review of the management plan, updating of master plan and the use of best practice guidelines for park management. It is hoped that the document contributes positively to park. management and visitors. Architectural Heritage Management wtd Tourism Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2006 Student's signature .. ~ .. \: ....~ .......... .. R hPr. Ad. ' . ~/ esearc qiect vISOr s signature ......... 1 ..... k .••.............................. ' ~ C ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The realization of this research project can be attributed to the extensive support and assistance from my advisor, Assistant Professor Den Wasiksiri and Professor Dr. -

Chapter 6 South-East Asia

Chapter 6 South-East Asia South-East Asia is the least compact among the extremity of North-East Asia. The contiguous ar- regions of the Asian continent. Out of its total eas constituting the continental interior include land surface, estimated at four million sq.km., the the highlands of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and mainland mass has a share of only 40 per cent. northern Vietnam. The relief pattern is that of a The rest is accounted for by several thousand is- longitudinal ridge and furrow in Myanmar and lands of the Indonesian and Philippine archipela- an undulating plateau eastwards. These are re- goes. Thus, it is composed basically of insular lated to their structural difference: the former and continental components. Nevertheless the being a zone of tertiary folds and the latter of orographic features on both these landforms are block-faulted massifs of greater antiquity. interrelated. This is due to the focal location of the region where the two great axes, one of lati- The basin of the Irrawady (Elephant River), tudinal Cretaceo-Tertiary folding and the other forming the heartland of Myanmar, is ringed by of the longitudinal circum-Pacific series, converge. mountains on three sides. The western rampart, This interface has given a distinctive alignment linking Patkai, Chin, and Arakan, has been dealt to the major relief of the region as a whole. In with in the South Asian context. The northern brief, the basic geological structures that deter- ramparts, Kumon, Kachin, and Namkiu of the mine the trend of the mountains are (a) north- Tertiary fold, all trend north-south parallel to the south and north-east in the mainland interior, (b) Hengduan Range and are the highest in South- east-west along the Indonesian islands, and (c) East Asia; and this includes Hkakabo Raz north-south across the Philippines. -

Khao Yai National Park

Khao Yai National Park Khao Yai National Park was established as the first national park of Thailand in 1962. The national park covers a total area of 2,165.55 square kilometres in the four provinces of Nakhon Nayok, Prachin Buri, Nakhon Ratchasima and Saraburi. Consisting of large forested areas, scenic beauty and biological diversity, Khao Yai National Park, together with other protected areas within the Dong Phaya Yen mountain range, are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Khao Yai or çBig Mountainé is home to a great diversity of flora and fauna, as well as pure beautiful nature. Geography A rugged mountain range dominates most areas of the park. Khao Rom is the highest peak towering at 1,351 metres above mean sea level. The region is the source of five main rivers, the Prachin Buri, acuminata, Vatica odorata, Shorea henryana, Hopea Nakhon Nayok, Lam Ta Khong, Lam Phra Phloeng ferrea, Tetrameles nudiflora, Pterocymbium tinctorium and Muak Lek stream. and Nephelium hypoleucum. Such rich wilderness is home to a large amount of Climate wildlife such as Asian Elephant, Northern Red Muntjac, The weather is warm all year round with an Sambar, Tiger, Guar, Southwest China Serow, Bears, average temperature of 23 degree Celsius. Porcupines, Gibbons, Black Giant Squirrel, Small Indian Civet and Common Palm Civet. Flora and Fauna There are over 200 bird species, including Great Mixed deciduous forest occupies the northern part Hornbill, Wreathed Hornbill, Tickell's Brown Hornbill, of the park with elevations ranging between 200-600 Hill Myna, Blue Magpie, Scarlet Minivet, Blue Pitta, metres. -

Freeland Final 2019

PUBLIC VERSION Section I. Project Information Project Title: Khao Laem: Conservation in one of Thailand’s Frontier Tiger Parks Grantee Organisation: Freeland Foundation Location of project: Khao Laem National Park Kanchanaburi Province, Western Thailand See map in appendix Size of project area (if appropriate): Size of PA – 1,496.93 km² Partners: Management of Khao Laem National Park, Department of National Parks Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP’s). Project Contact Name: Tim Redford Email: Reporting period: February 2019 to February 2020 (13 months) Section II. Project Results Long Term Impact: This survey project led by Khao Laem National Park for the first time categorically proves the presence of tigers at this site and progressed the recovery of tigers in Thailand by ensuring these tigers are recorded and included into tiger conservation planning, especially important for the concluding review of outcomes from the current Tiger Action Plan 2012-2022. Such information will also help prioritise protected areas for inclusion in the successive tiger action plan due in 2022. We anticipate such understanding will assist KLNP site gain increased government support, which will help ensure the long- term protection of Indochinese tigers. This is relevant both at this site and across the South Western Forest Complex (sWEFCOM) as protected areas are contiguous and tigers can disperse in any direction. While implementing this project we have learnt about gaps in forest connectivity, which if closed will give enhanced protection, or integrated into existing protected areas may improve dispersal corridors. Equipped with this information we can now look at ways to discuss those sites with the relevant agencies to understand why they exist in the first place and if the corridor status may be altered, as a way to enhance protection. -

Thailand R I R Lmplemen'rationof Aaicl¢6 of Theconvcntio Lon Biologicaldiversity

r_ BiodiversityConservation in Thailand r i r lmplemen'rationof Aaicl¢6 of theConvcntio_lon BiologicalDiversity Muw_ny of _e_cl reCUr _ eNW_WM#_ I Chapter 1 Biodiversity and Status 1 Species Diversity 1 Genetic Diversity 10 [cosystem Diversity 13 Chapter 2 Activities Prior to the Enactment of the National Strategy on Blodiversity 22 Chapter 3 National Strategy for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity 26 Chapter 4 Coordinating Mechanisms for the Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity $5 Chapter 5 International Cooperation and Collaboration 61 Chapter 6 Capacity for an Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity 70 Annex I National Policies, Measures and Plans on the Conservation and Sustainable Utilization of Biodiversity 1998-2002 80 Annex H Drafted Regulation on the Accress and Transfer of Biological Resources 109 Annex IH Guideline on Biodiversity Data Management (BDM) 114 Annex IV Biodiversity Data Management Action Plan 130 Literature 140 ii Biodiversity Conservation in Thailand: A National Report Preface Regular review of state of biodiversity and its conservation has been recognized by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) as a crucial element in combatting loss of biodiversity. Under Article 6, the Convention's Contracting Parties are obligated to report on implementation of provisions of the Convention including measures formulated and enforced. These reports serve as valuable basic information for operation of the Convention as well as for enhancing cooperation and assistance of the Contracting Parties in achieving conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Although Thailand has not yet ratified the Convention, the country has effectively used its provisions as guiding principles for biodiversity conservation and management since the signing of the Convention in 1992.