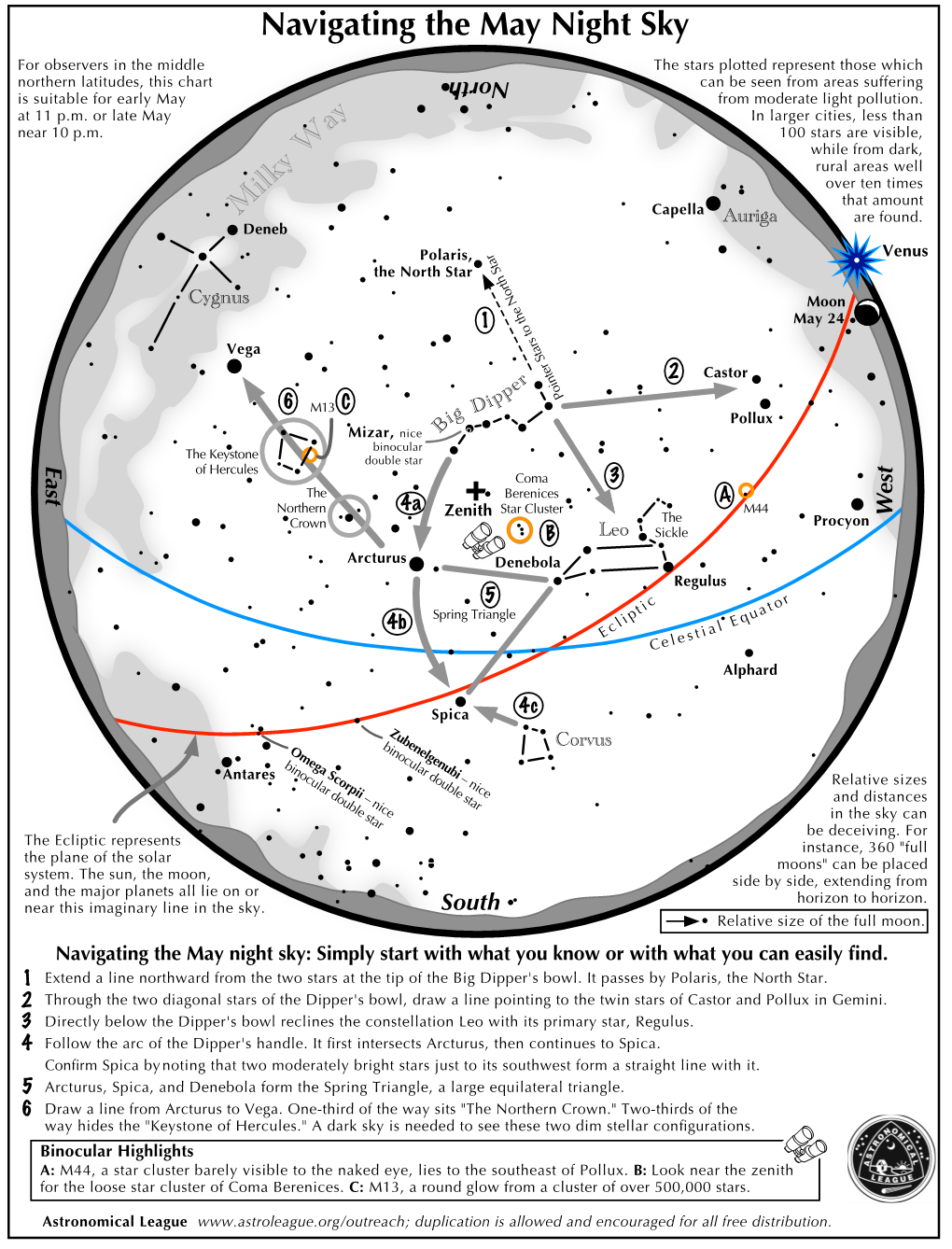

Navigating the May Night Sky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messier 58, 59, 60, 89, and 90, Galaxies in Virgo

Messier 58, 59, 60, 89, and 90, Galaxies in Virgo These are five of the many galaxies of the Coma-Virgo galaxy cluster, a prime hunting ground for galaxy observers every spring. Dozens of galaxies in this cluster are visible in medium to large amateur telescopes. This star hop includes elliptical galaxies M59, M60, and M89, and spiral galaxies M58 and M90. These galaxies are roughly 50 to 60 million light years away. All of them are around magnitude 10, and should be visible in even a small telescope. Start by finding the Spring Triangle, which consists of three widely- separated first magnitude stars-- Arcturus, Spica, and Regulus. The Spring Triangle is high in the southeast sky in early spring, and in the southwest sky by mid-Summer. (To get oriented, you can use the handle of the Big Dipper and "follow the arc to Arcturus"). For this star hop, look in the middle of the Spring Triangle for Denebola, the star representing the back end of Leo, the lion, and Vindemiatrix, a magnitude 2.8 star in Virgo. The galaxies of the Virgo cluster are found in the area between these two stars. From Vindemiatrix, look 5 degrees west and slightly south to find ρ (rho) Virginis, a magnitude 4.8 star that is easy to identify because it is paired with a slightly dimmer star just to its north. Center ρ in the telescope with a low-power eyepiece, and then just move 1.4 degrees north to arrive at the oval shape of M59. Continuing with a low-power eyepiece and using the chart below, you can take hops of less than 1 degree to find M60 to the east of M59, and M58, M89, and M90 to the west and north. -

Remote Video Astronomy Group MECATX Sky Tour May 2020

Remote Video Astronomy Group MECATX Sky Tour May 2020 1) Boötes (bo-OH-teez), the Herdsman - May 2 2) Libra (LEE-bruh), the Scales - May 9 3) Lupus (LOOP-us), the Wolf - May 9 4) Ursa Minor (ER-suh MY-ner), the Little Bear - May 13 5) Corona Borealis (cuh-ROE-nuh bor-ee-AL-iss) the Northern Crown - May 19 6) Norma (NOR-muh), the Carpenter's Square - May 19 7) Apus (APE-us), the Bird of Paradise - May 21 8) Triangulum Australe (try-ANG-gyuh-lum aw-STRAL-ee), the Southern Triangle - May 23 9) Draco (DRAY-co), the Dragon - May 24 MECATX RVA May 2019 - www.mecatx.ning.com – YouTube – MECATX – www.ustream.tv – dfkott Revised: Alyssa Donnell 04.19.2020 May 2 Boötes (bo-OH-teez), the Herdsman Boo Boötis (bo-OH-tiss) MECATX RVA May 2019 - www.mecatx.ning.com – YouTube – MECATX – www.ustream.tv – dfkott 1 Boötes Meaning: The Bear Driver Pronunciation: bow owe' teez Abbreviation: Boo Possessive form: Boötis (bow owe' tiss) Asterisms: The Diamond [of Virgo], The Ice Cream Cone, The Kite, The Spring Triangle, The Trapezoid Bordering constellations: Canes Venatici, Coma Berenices, Corona Borealis, Draco, Hercules, Serpens, Ursa Major, Virgo Overall brightness: 5.845 (59) Central point: RA = 14h40m Dec.= +31° Directional extremes: N = +55° S = +7° E = 15h47m W = 13h33m Messier objects: none Meteor showers: Quadrantids (3 Jan),4 Boötids (1 May), a Boötids (28 Apr), June Bootids (28 Jun) Midnight culmination date: 2 May Bright stars: a (4), F, (78), i (106), y (175) Named stars: Arcturus (a), Hans (y), Izar (s), Merez (3), Merga (38), Mufrid (ii), Nekkar -

Asterism and Constellation: Terminological Dilemmas

www.ebscohost.com www.gi.sanu.ac.rs, www.doiserbia.nb.rs, J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic. 67(1) (1–10) Original scientific paper UDC: 521/525 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2298/IJGI1701001P ASTERISM AND CONSTELLATION: TERMINOLOGICAL DILEMMAS Zorica Prnjat *1, Milutin Tadić * * University of Belgrade, Faculty of Geography, Belgrade, Serbia Received: March 14, 2017; Reviewed: March 23, 2017; Accepted: March 31, 2017 Abstract: In contemporary astronomical literature, there is no uniform definition of the term asterism. This inconsistency is the consequence of differences between the traditional understanding of the term constellation, from the standpoint of the naked eye astronomy, and its contemporary understanding from the standpoint of the International Astronomical Union. A traditional constellation is a recognizable star configuration with a well-established name, whereas the International Astronomical Union defines a constellation as an exactly defined sector of the cosmic space that belongs to a particular traditional constellation. Asterism is a lower rank term in comparison to constellation, and as such it may not denote a whole traditional constellation, as these terms would become synonymous and parts of constellations would become “asterisms of asterisms“. Similarly, asterism cannot define a macro configuration composed of the brightest stars in more constellations, thus, the Summer Triangle and other sky polygons are not asterisms. Therefore, asterisms are neither constellations nor sky polygons, but the third – easily recognizable parts of traditional constellations with historically well-established names, including separate groups of smaller stars that belong to star clusters (autonomous asterisms). Forms and names of asterisms may or may not be consistent with the parent constellation, and accordingly asterisms can be divided into compatible and incompatible. -

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report Eric Mamajek (chair, USA) WG Members: Juan Antonio Belmote Avilés (Spain), Sze-leung Cheung (Thailand), Beatriz García (Argentina), Steven Gullberg (USA), Duane Hamacher (Australia), Susanne M. Hoffmann (Germany), Alejandro López (Argentina), Javier Mejuto (Honduras), Thierry Montmerle (France), Jay Pasachoff (USA), Ian Ridpath (UK), Clive Ruggles (UK), B.S. Shylaja (India), Robert van Gent (Netherlands), Hitoshi Yamaoka (Japan) WG Associates: Danielle Adams (USA), Yunli Shi (China), Doris Vickers (Austria) WGSN Website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/ WGSN Email: [email protected] The Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) consists of an international group of astronomers with expertise in stellar astronomy, astronomical history, and cultural astronomy who research and catalog proper names for stars for use by the international astronomical community, and also to aid the recognition and preservation of intangible astronomical heritage. The Terms of Reference and membership for WG Star Names (WGSN) are provided at the IAU website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/. WGSN was re-proposed to Division C and was approved in April 2019 as a functional WG whose scope extends beyond the normal 3-year cycle of IAU working groups. The WGSN was specifically called out on p. 22 of IAU Strategic Plan 2020-2030: “The IAU serves as the internationally recognised authority for assigning designations to celestial bodies and their surface features. To do so, the IAU has a number of Working Groups on various topics, most notably on the nomenclature of small bodies in the Solar System and planetary systems under Division F and on Star Names under Division C.” WGSN continues its long term activity of researching cultural astronomy literature for star names, and researching etymologies with the goal of adding this information to the WGSN’s online materials. -

Messier 61, Oriani's Galaxy

Messier 61, Oriani’s Galaxy This beautiful face-on barred spiral galaxy was discovered in 1779 by Barnabas Oriani, a Catholic priest and accomplished astronomer, and it became the 61st entry in Messier's catalog. It is on the southern outskirts of the Virgo galaxy cluster. Through small scopes, it appears as a circular glow with a brighter center. Large scopes will show its two large spiral arms. Start by finding the Spring Triangle, which consists of three widely- separated first magnitude stars-- Arcturus, Spica, and Regulus. The Spring Triangle is high in the southeast sky in early spring, and in the southwest sky by mid-Summer. (To get oriented, you can use the handle of the Big Dipper and "follow the arc to Arcturus"). For this star hop, look in the middle of the Spring Triangle for Denebola, the star representing the back end of Leo, the lion, and Vindemiatrix, a magnitude 2.8 star in Virgo. The galaxies of the Virgo cluster are found in the area between these two stars. From Vindemiatrix, trace the curving arc of stars that form part of the constellation Virgo to reach Zaniah, as shown below. All of these stars should be easy to see with the naked eye under a clear sky. From Zaniah, move 4 degrees north to a 5th magnitude star that will be easily visible in binoculars or a finderscope. Center this star in your telescope with a low-power eyepiece, then move a little more than 1 degree to the north- northeast to reach M61. Star hop from www.skyledge.net by Jim Mazur. -

Observing the Way It Was Meant to Be Nothing Is Better Than Observing Under a Dark, Clear, Steady Sky

THE CIGaR GALAXY (M82) in Ursa deep-sky observing Major is a great object for 6-inch or larger telescopes. Through a 30-inch What we saw through a 30-inch telescope under an inky black sky scope at 736x, however, it ranks as a blew our minds. ⁄ ⁄ ⁄ BY michael e. Bakich spectacular sight. Tony and daphne hallas Observing the way it was meant to be Nothing is better than observing under a dark, clear, steady sky. Wait, one thing’s better — observing that sky through a large scope. In February, I had the opportunity to do just that under the pristine conditions at Arizona Sky Village (ASV), located in Portal, Arizona. As a guest of real-estate developer Eugene more detail you’ll see. If you double the Turner, I had 2 nights with Turner’s superb aperture, you capture 4 times as much 30-inch Starmaster telescope. light. So, an 8-inch telescope gathers 4 The 30-inch is a high-quality Newto- times as much light as a 4-inch. nian reflector on a Dobsonian mount. I’d But there’s another advantage to all the THE GhOsT OF JUPiTeR (NGC 3242) is a used this telescope one year earlier, with light a large scope collects. The object may small object. Its bright inner sphere mea- Astronomy’s editor, David J. Eicher. We appear bright enough to trigger your eyes’ sures only 25" across. Seeing the 40"-wide observed many celestial wonders in Orion color receptors. A planetary nebula that outer halo and fine details requires a large and the rest of the winter sky. -

Estimation of the XUV Radiation Onto Close Planets and Their Evaporation⋆

A&A 532, A6 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201116594 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics Estimation of the XUV radiation onto close planets and their evaporation J. Sanz-Forcada1, G. Micela2,I.Ribas3,A.M.T.Pollock4, C. Eiroa5, A. Velasco1,6,E.Solano1,6, and D. García-Álvarez7,8 1 Departamento de Astrofísica, Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC Campus, PO Box 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo G. S. Vaiana, Piazza del Parlamento, 1, 90134, Palermo, Italy 3 Institut de Ciènces de l’Espai (CSIC-IEEC), Campus UAB, Fac. de Ciències, Torre C5-parell-2a planta, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain 4 XMM-Newton SOC, European Space Agency, ESAC, Apartado 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 5 Dpto. de Física Teórica, C-XI, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain 6 Spanish Virtual Observatory, Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC Campus, Madrid, Spain 7 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Spain 8 Grantecan CALP, 38712 Breña Baja, La Palma, Spain Received 27 January 2011 / Accepted 1 May 2011 ABSTRACT Context. The current distribution of planet mass vs. incident stellar X-ray flux supports the idea that photoevaporation of the atmo- sphere may take place in close-in planets. Integrated effects have to be accounted for. A proper calculation of the mass loss rate through photoevaporation requires the estimation of the total irradiation from the whole XUV (X-rays and extreme ultraviolet, EUV) range. Aims. The purpose of this paper is to extend the analysis of the photoevaporation in planetary atmospheres from the accessible X-rays to the mostly unobserved EUV range by using the coronal models of stars to calculate the EUV contribution to the stellar spectra. -

A Pulsar Is Really a Neutron Star, Which Forms After a Big Star Goes Supernova and Its Remnant Core Collapses Down Into a Very Dense Object

Question 1: Dear Cheap Astronomy – What do different pulsar frequencies mean? A pulsar is really a neutron star, which forms after a big star goes supernova and its remnant core collapses down into a very dense object. Star routinely spin, for example the Sun rotates around once every 25 days, so when the core of a really big star collapses right down to an object that’s only 20 kilometres in diameter, conservation of momentum means that object will spin really fast, like when the spinning ice skater pulls her arms in. Although a neutron star is primarily composed of lots of neutrons, largely arising from the compressed fusion of electrons and protons, a substantial number of free charged particles still remain which gives neutron stars powerful magnetic fields, which when spun up create electrical fields which channel the charged particles up towards the poles where they are squeezed together until they shoot out, as though by a firehose, because the electromagnetic forces pushing on them overcome the gravity of the neutron star. Through a mechanism that is not well understood the ejected particles electrically dissociate in some way causing a powerful emission of radio waves in line with the particle jets, which is what we detect from Earth. Two radio beams come from each of the magnetic poles, which do not precisely align with the neutron star’s rotational poles. So, when the neutron star’s rotational axis approximately aligns with Earth, its spin can bring that beam into line with us once per rotation. And since neutron stars spin fast, generally many times a second, we detect this as rapid flashes of radio light. -

Poster Size (PDF Format 406 Kbytes)

Navigating the Spring Night Sky North North For observers in the middle northern The stars plotted represent those which latitudes, this chart is suitable for late can be seen from areas suffering April at 10:30 p.m. or early May from moderate light pollution. In at 10:00 p.m. Way larger cities, less than 100 stars are visible, while from dark rural areas well over ten times Milky Milky that amount are found. Vega Polaris, Capella the North Star 2 9 1 Auriga The Keystone of Hercules The Big Dipper 3 Gemini Castor East Pollux Coma 5 Way The Northern Berenices 4 West Cluster The Crown Beehive Arcturus Leo The Sickle Denebola Procyon Milky Milky The Spring 8 Regulus 6 Triangle The Ecliptic Spica 7 Relative Corvus sizes and distances in the sky can be deceiving. For instance, 360 “full The Ecliptic line moons” can be placed represents the plane of side by side extending the solar system. The sun, from horizon to horizon. the moon, and the major planets all lie on or near this South Relative size imaginary line in the sky. of the full moon Navigating the spring night sky isn’t difficult. Simply start with what you know or with what you can easily find. At this time of year in the early evening, the Big Dipper lies nearly overhead. 1 Extend an imaginary line directly north from the two stars at the tip of the Dipper’s bowl. It passes by Polaris, the North Star. 2 Draw another imaginary line across the top two stars of the Dipper’s bowl. -

The Universe Contents 3 HD 149026 B

History . 64 Antarctica . 136 Utopia Planitia . 209 Umbriel . 286 Comets . 338 In Popular Culture . 66 Great Barrier Reef . 138 Vastitas Borealis . 210 Oberon . 287 Borrelly . 340 The Amazon Rainforest . 140 Titania . 288 C/1861 G1 Thatcher . 341 Universe Mercury . 68 Ngorongoro Conservation Jupiter . 212 Shepherd Moons . 289 Churyamov- Orientation . 72 Area . 142 Orientation . 216 Gerasimenko . 342 Contents Magnetosphere . 73 Great Wall of China . 144 Atmosphere . .217 Neptune . 290 Hale-Bopp . 343 History . 74 History . 218 Orientation . 294 y Halle . 344 BepiColombo Mission . 76 The Moon . 146 Great Red Spot . 222 Magnetosphere . 295 Hartley 2 . 345 In Popular Culture . 77 Orientation . 150 Ring System . 224 History . 296 ONIS . 346 Caloris Planitia . 79 History . 152 Surface . 225 In Popular Culture . 299 ’Oumuamua . 347 In Popular Culture . 156 Shoemaker-Levy 9 . 348 Foreword . 6 Pantheon Fossae . 80 Clouds . 226 Surface/Atmosphere 301 Raditladi Basin . 81 Apollo 11 . 158 Oceans . 227 s Ring . 302 Swift-Tuttle . 349 Orbital Gateway . 160 Tempel 1 . 350 Introduction to the Rachmaninoff Crater . 82 Magnetosphere . 228 Proteus . 303 Universe . 8 Caloris Montes . 83 Lunar Eclipses . .161 Juno Mission . 230 Triton . 304 Tempel-Tuttle . 351 Scale of the Universe . 10 Sea of Tranquility . 163 Io . 232 Nereid . 306 Wild 2 . 352 Modern Observing Venus . 84 South Pole-Aitken Europa . 234 Other Moons . 308 Crater . 164 Methods . .12 Orientation . 88 Ganymede . 236 Oort Cloud . 353 Copernicus Crater . 165 Today’s Telescopes . 14. Atmosphere . 90 Callisto . 238 Non-Planetary Solar System Montes Apenninus . 166 How to Use This Book 16 History . 91 Objects . 310 Exoplanets . 354 Oceanus Procellarum .167 Naming Conventions . 18 In Popular Culture . -

IAU WGSN 2019 Annual Report

IAU Division C Working Group on Star Names 2019 Annual Report Eric Mamajek (chair, USA) WG Members: Juan Antonio Belmote Avilés (Spain), Sze-leung Cheung (Thailand), Beatriz García (Argentina), Steven Gullberg (USA), Duane Hamacher (Australia), Susanne M. Hoffmann (Germany), Alejandro López (Argentina), Javier Mejuto (Honduras), Thierry Montmerle (France), Jay Pasachoff (USA), Ian Ridpath (UK), Clive Ruggles (UK), B.S. Shylaja (India), Robert van Gent (Netherlands), Hitoshi Yamaoka (Japan) WG Associates: Danielle Adams (USA), Yunli Shi (China), Doris Vickers (Austria) WGSN Website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/ WGSN Email: [email protected] The Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) consists of an international group of astronomers with expertise in stellar astronomy, astronomical history, and cultural astronomy who research and catalog proper names for stars for use by the international astronomical community, and also to aid the recognition and preservation of intangible astronomical heritage. The Terms of Reference and membership for WG Star Names (WGSN) are provided at the IAU website: https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/. WGSN was re-proposed to Division C and was approved in April 2019 as a functional WG whose scope extends beyond the normal 3-year cycle of IAU working groups. The WGSN was specifically called out on p. 22 of IAU Strategic Plan 2020-2030: “The IAU serves as the internationally recognised authority for assigning designations to celestial bodies and their surface features. To do so, the IAU has a number of Working Groups on various topics, most notably on the nomenclature of small bodies in the Solar System and planetary systems under Division F and on Star Names under Division C.” WGSN continues its long term activity of researching cultural astronomy literature for star names, and researching etymologies with the goal of adding this information to the WGSN’s online materials. -

Full Program

1 Schedule Abstracts Author Index 2 Schedule Schedule ............................................................................................................................... 3 Abstracts ............................................................................................................................... 5 Monday, September 12, 2011, 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM ................................................................................ 5 01: Overview of Observations and Welcome ....................................................................................... 5 Monday, September 12, 2011, 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM .............................................................................. 7 02: Radial Velocities ............................................................................................................................. 7 Monday, September 12, 2011, 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM ................................................................................ 10 03: Transiting Planets ......................................................................................................................... 10 Monday, September 12, 2011, 4:00 PM - 5:30 PM ................................................................................ 13 04: Transiting Planets II ...................................................................................................................... 13 Tuesday, September 13, 2011, 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM .............................................................................. 16 05: Planets