Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Mike by P.G. Wodehouse Mike and Psmith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wodehouse - UK and US Editions

Wodehouse - UK and US editions UK Title Year E.L US Title Norwegian A Damsel in Distress 1919 x En jomfru i nød A Few Quick Ones 1959 x A Gentleman of Leisure 1910 x The Intrusion of Jimmy A Man of Means (med C. H. Bovill, UK) 1991 x A Pelican at Blandings 1969 x No Nudes is Good Nudes A Prefect's Uncle 1903 x A Prince for Hire 2003 0 A Wodehouse Miscellany (e-bok) 2003 0 Aunts Aren't Gentlemen 1974 x The Cat-nappers Tanter er ikke Gentlemen Bachelors Anonymous 1973 x Anonyme Peppersvenner Barmy in Wonderland 1952 x Angel Cake Big Money 1931 x Penger som gress Bill the Conqueror 1924 x Blandings Castle and Elsewhere 1935 x Blandings Castle Bring on the Girls 1953 x Carry on Jeeves 1925 x Cocktail Time 1958 x Company for Henry 1967 x The Purloined Paperweight Death At the Excelsior and Other Stories (e-bok) 2003 0 Do Butlers Burgle Banks 1968 x Doctor Sally 1932 x Eggs, Beans and Crumpets 1940 x French Leave 1956 x Franskbrød og arme riddere Frozen Assets 1964 x Biffen's Millions Full Moon 1947 x Månelyst på Blandings Galahad at Blandings 1968 x The Binkmanship of Galahad Threepwood Heavy Weather 1933 x Salig i sin tro Hot Water 1932 x Høk over høk Ice in the Bedroom 1961 x The Ice in the Bedroom Gjemt men ikke glemt If I Were You 1931 x Indiscretions of Archie 1921 x Side 1 av 4 / presented by blandings.no Wodehouse - UK and US editions UK Title Year E.L US Title Norwegian Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit 1954 x Bertie Wooster Sees it Through Jeg stoler på Jeeves Jeeves in the Offing 1960 x How Right You Are, Jeeves S.O.S. -

Autumn-Winter 2002

Beyond Anatole: Dining with Wodehouse b y D a n C o h en FTER stuffing myself to the eyeballs at Thanks eats and drinks so much that about twice a year he has to A giving and still facing several days of cold turkey go to one of the spas to get planed down. and turkey hash, I began to brood upon the subject Bertie himself is a big eater. He starts with tea in of food and eating as they appear in Plums stories and bed— no calories in that—but it is sometimes accom novels. panied by toast. Then there is breakfast, usually eggs and Like me, most of Wodehouse’s characters were bacon, with toast and marmalade. Then there is coffee. hearty eaters. So a good place to start an examination of With cream? We don’t know. There are some variations: food in Wodehouse is with the intriguing little article in he will take kippers, sausages, ham, or kidneys on toast the September issue of Wooster Sauce, the journal of the and mushrooms. UK Wodehouse Society, by James Clayton. The title asks Lunch is usually at the Drones. But it is invariably the question, “Why Isn’t Bertie Fat?” Bertie is consistent preceded by a cocktail or two. In Right Hoy Jeeves, he ly described as being slender, willowy or lissome. No describes having two dry martinis before lunch. I don’t hint of fat. know how many calories there are in a martini, but it’s Can it be heredity? We know nothing of Bertie’s par not a diet drink. -

Verkf\366Rteckning \345T WS 3 Sept 2017, Uppdaterad

Verkförteckning. BÖCKER på svenska: *1) Årtal/Titel/Översättare 1943/All right, Jeeves!/ Right Ho, Jeeves!/Birgitta Hammar 1950/Alla tiders Wodehouse/ Flertal böcker *2)/Birgitta Hammar 1963/Alltid till er tjänst/ Service with a Smile/Birgitta Hammar/Mons Mossner 1937/Bill Erövraren/ Bill the Conqueror/Vilgot Hammarling 1933/Billie och hennes friare/ The Girl on the Boat/Kerstin Wimnell 2011/Bland lorder och drönare/ Flertal böcker *3)/Flera. Många okända 1935/Blixt och dunder/ Summer Lightning/Vilgot Hammarling 1947/Bravo, Jeeves!/ Joy in the Morning/Birgitta Hammar 1969/Brukar betjänter begå bankrån?/ Do Butlers Burgle Banks?/Birgitta Hammar 1959/Cocktaildags/ Cocktail Time/Birgitta Hammar 1996/De bästa golfhistorierna/ Delar av The Golf Omnibus/Birgitta Hammar 1960/Den oefterhärmlige Jeeves/ The Inimitable Jeeves/Birgitta Hammar 1931/Den oförliknelige Jeeves / The Inimitable Jeeves/Kerstin Wimnell 1925/Den okända som han älskade/ A Gentleman of Leisure/- Okänd 1957/Den oumbärlige Jeeves/ Flera böcker *4)/Birgitta Hammar 1939/Den vita fjädern / The White Feather/Axel Essén 1978/Det våras på Blandings/ Something Fresh/Birgitta Hammar 1923/Dick Underhills fästmö/ Jill the Reckless/Harald Johnsson 2010/Drönarhistorier/ Young Men in Spats *5)/- Okända 2013/Döden på Excelsior/ Flertal tidskrifter *6)/Bengt Malmberg 1937/En blyg ung man/ The Small Bachelor/Martin Loya 1921/En flicka i trångmål/ A Damsel in Distress/Ulla Rudebeck 1970/En pelikan på Blandings/ A Pelican at Blandings/Birgitta Hammar 1967/Ett upp för Cuthbert/ The Clicking of -

Psmith in Pseattle: the 18Th International TWS Convention It’S Going to Be Psensational!

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 35 Number 4 Winter 2014 Psmith in Pseattle: The 18th International TWS Convention It’s going to be Psensational! he 18th biennial TWS convention is night charge for a third person, but Tless than a year away! That means there children under eighteen are free. are a lot of things for you to think about. Reservations must be made before While some of you avoid such strenuous October 8, 2015. We feel obligated activity, we will endeavor to give you the to point out that these are excellent information you need to make thinking as rates both for this particular hotel painless as possible. Perhaps, before going and Seattle hotels in general. The on, you should take a moment to pour a stiff special convention rate is available one. We’ll wait . for people arriving as early as First, clear the dates on your calendar: Monday, October 26, and staying Friday, October 30, through Sunday, through Wednesday, November 4. November 1, 2015. Of course, feel free to Third, peruse, fill out, and send come a few days early or stay a few days in the registration form (with the later. Anglers’ Rest (the hosting TWS chapter) does appropriate oof), which is conveniently provided with have a few activities planned on the preceding Thursday, this edition of Plum Lines. Of course, this will require November 29, for those who arrive early. There are more thought. Pour another stiff one. You will have to many things you will want to see and do in Seattle. -

Summer 2004 Through the Covers.” Attempted to Get the Committee to Revoke Its Approval “Do You Know What Means? ‘Crack Them Through of the Topic

St. Mike’s, Wodehouse, and Me: The Great Thesis Handicap did my undergraduate work here at St. Michael’s College BY ELLIOTT MILSTEIN from 1971 to 1976. How an American Jew ended up at a Catholic Canadian University is another story. I must Editor’s note: Elliott Milstein was primary perpetrator of and opening say, however, that planning this convention on the speaker at The Wodehouse Society convention held in Toronto last site of my alma mater, not to mention attending my August. This is Part 1 of Elliott’s talk; tune in to the next issue to read daughter’s graduation ceremonies this past June with his exciting conclusion. all its attendant festivities and speeches, has put me in a nostalgic mood, and all of you are about to become the unwitting victims of this mood. I was introduced to P. G. Wodehouse by my father at the tender age of 12. Having announced to him that I had read everything of interest there was to read (I had finished off the Tom Swift series, you understand), I complained bitterly that there was nothing left in life. He handed me his tattered old (first edition, you understand) Nothing But Wodehouse and instructed me to begin at the end with Leave It to Psmith. Now, if this were a fairy tale, I would tell you that from that moment on I never looked back, but I must be totally honest with you. I found it silly. I did not even get through the first chapter, and I returned it to him. -

Information Sheet Number 9A a Simplified Chronology of PG

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 9a A Simplified Chronology of P G Wodehouse Fiction Revised December 2018 Note: In this Chronology, asterisked numbers (*1) refer to the notes on pages (iv) and (v) of Information Sheet Number 9 The titles of Novels are printed in a bold italic font. The titles of serialisations of Novels are printed in a bold roman font. The titles of Short Stories are printed in a plain roman font. The titles of Books of Collections of Short Stories are printed in italics and underlined in the first column, and in italics, without being underlined, when cited in the last column. Published Novel [Collection] Published Short Story [Serial] Relevant Collection [Novel] 1901 SC The Prize Poem Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC L’Affaire Uncle John Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC Author! Tales of St Austin’s (1903) 1902 SC The Pothunters The Pothunters SC The Babe and the Dragon Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC “ The Tabby Terror ” Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC Bradshaw’s Little Story Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC The Odd Trick Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC The Pothunters SC How Payne Bucked Up Tales of St Austin’s (1903) 1903 SC Harrison’s Slight Error Tales of St Austin’s SC How Pillingshot Scored Tales of St Austin’s SC The Manoeuvres of Charteris Tales of St Austin’s SC A Prefect’s Uncle SC The Gold Bat The Gold Bat (1904) SC Tales of St Austin’s A Shocking Affair 1 Published Novel [Collection] Published Short Story [Serial] Relevant Collection [Novel] 1904 SC The Gold Bat SC The Head of Kay’s The Head -

Novels by P G Wodehouse Appearing in Magazines

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 4 Revised December 2018 Novels by P G Wodehouse appearing in Magazines Of the novels written by P G Wodehouse, the vast majority were serialised in magazines, some appearing in a single issue. The nature of the serialisation changed with time. The early novels were serialised in almost identical form to the published book, but from the mid-1930s there was an increasing tendency for the magazine serialisation to be a condensed version of the novel. In some cases, the condensed version was written first. Attention is drawn in particular to the following titles: The Prince and Betty, which in both the first UK and first US magazine appearances, was based on the UK rather than the very different US book version of the text. A Prince for Hire, which was a serialised novelette based broadly on The Prince and Betty, but completely rewritten in 1931. The Eighteen Carat Kid, which in serial form consisted only of the adventure aspects of The Little Nugget, the love interest being added to ‘flesh out’ the book. Something New, which contained a substantial scene from The Lost Lambs (the second half of Mike) which was included in the American book edition, but not in Something Fresh, the UK equivalent. Leave It To Psmith, the magazine ending of which in both the US and the UK was rewritten for book publication in both countries. Laughing Gas, which started life as a serial of novelette length, and was rewritten for book publication to more than double its original length. -

By the Way Sept 08.Qxd

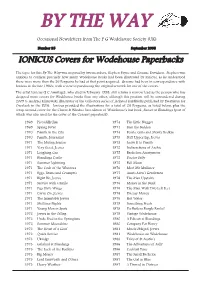

BY THE WAY Occasional Newsletters from The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Number 35 September 2008 IONICUS Covers for Wodehouse Paperbacks The topic for this By The Way was inspired by two members, Stephen Payne and Graeme Davidson. Stephen was anxious to confirm precisely how many Wodehouse books had been illustrated by Ionicus, as he understood there were more than the 56 Penguins he had at that point acquired. Graeme had been in correspondence with Ionicus in the late 1980s, with a view to purchasing the original artwork for one of the covers. The artist Ionicus (J C Armitage), who died in February 1998, still retains a narrow lead as the person who has designed more covers for Wodehouse books than any other, although this position will be surrendered during 2009 to Andrzej Klimowski, illustrator of the Collectors series of jacketed hardbacks published by Everyman (or Overlook in the USA). Ionicus provided the illustrations for a total of 58 Penguins, as listed below, plus the wrap-around cover for the Chatto & Windus first edition of Wodehouse’s last book, Sunset at Blandings (part of which was also used for the cover of the Coronet paperback). 1969 Piccadilly Jim 1974 The Little Nugget 1969 Spring Fever 1974 Sam the Sudden 1970 Psmith in the City 1974 Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin 1970 Psmith, Journalist 1975 Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves 1971 The Mating Season 1975 Leave It to Psmith 1971 Very Good, Jeeves 1975 Indiscretions of Archie 1971 Laughing Gas 1975 Bachelors Anonymous 1971 Blandings Castle 1975 Doctor Sally 1971 Summer Lightning -

P.G. Wodehouse Collection of William Toplis (1665) Lot

P.G. Wodehouse Collection of William Toplis (1665) May 7, 2020 EDT, ONLINE ONLY Lot 176 Estimate: $3000 - $5000 (plus Buyer's Premium) Wodehouse, P.G. P.G. Wodehouse's Personal Scrapbooks 1911-1960. In four volumes. P.G. Wodehouse's personal scrapbooks. Compiled over an almost 50-year period. Each scrapbook contains primarily newspaper clippings and magazine articles from around the world, documenting the release of his novels and plays, as well as essays and reviews of his work. Novels and plays such as "A Gentleman of Leisure" (1911), Big Money (1931), Hot Water (1932), Laughing Gas (1936) are documented, as well as numerous other articles on Blandings Castle, the Drones Club, and Jeeves, as well as other articles on Wodehouse himself. Each in black cloth-covered fall-down-back box. Size and condition varies. Comprising: Scrapbook One: 1911-1913 Hundreds of newspaper clippings, and other paper ephemera relating to the play "A Gentleman of Leisure" (New York: The Playhouse, 1911. McIlvaine J5) and "A Thief for a Night" (Chicago: McVicker's Theater, 1913. McIlvaine J6). Contains numerous telegrams from John Stapleton, playwright who adapted the novel with Wodehouse. Pages very brittle, many separated, numerous newspaper clippings chipped. Scrapbook Two: June, 1931-53 Hundreds of newspaper clippings, articles, and reviews. Stories and novels represented, including, Big Money, Very Good Jeeves, Summer Moonshine, Leave it to Psmith, Performing Flea, Blandings Castle, and the Drones Club. Many sheets separating and loose; scattered marginalia. Scrapbook Three: December, 1932-36 Hundreds of newspaper clippings, relating to Nothing But Wodehouse, Louder & Funnier, Hot Water, Mulliner Nights, Heavy Weather, Right Ho Jeeves, Laughing Gas, and others. -

Autumn 2004 Wodehouse in America N His New Biography of P

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 25 Number 3 Autumn 2004 Wodehouse in America n his new biography of P. G. Wodehouse, Robert IMcCrum writes: “On a strict calculation of the time Wodehouse eventually spent in the United States, and the lyrics, books, stories, plays and films he wrote there, to say nothing of his massive dollar income, he should be understood as an American and a British writer.” The biography Wodehouse: A Life will be published in the United States in November by W.W. Norton & Co., and will be reviewed in the next issue of Plum Lines. McCrum’s book presents the American side of Wodehouse’s life and career more fully than any previous work. So with the permission of W.W. Norton, we present some advance excerpts from the book concerning Plum’s long years in America. First trip Wodehouse sailed for New York on the SS St. Louis on 16 April 1904, sharing a second-class cabin with three others. He arrived in Manhattan on 25 April, staying on Fifth Avenue with a former colleague from the bank. Like many young Englishmen, before and since, he found it an intoxicating experience. To say that New York lived up to its advance billing would be the baldest of understatements. ‘Being there was like being in heaven,’ he wrote, ‘without going to all the bother and expense of dying.’ ‘This is the place to be’ Wodehouse later claimed that he did not intend to linger in America but, as in 1904, would just take a perhaps he had hoped to strike gold. -

P. G. Wodehouse Linguist?1

Connotations Vol. 15.1-3 (2005/2006) P. G. Wodehouse Linguist?1 BARBARA C. BOWEN One of the world’s great comic writers, “English literature’s perform- ing flea” (according to Sean O’Casey), a linguist? Surely not. In the first place, we Brits have traditionally been resistant to learning for- eign languages (on the grounds that English should be good enough for everybody); in the second place, PG received the then-standard English public-school education, which stressed Latin and Greek but certainly not any living foreign languages; in the third place the only foreign countries he visited, as far as I know, were France, Germany (through no fault of his own), and the United States, which became his home. Critics have not to my knowledge ever thought of him as a linguist; when Thelma Cazalet-Keir says “For me it is in his use of language that Mr. Wodehouse appears supremely,” she is thinking of his highly literary style and “concentration of verbal felicities.”2 But linguists are born, not made, and this article will contend that PG had a natural gift for language, both for the almost endless varia- tions on his own, and for a surprising number of foreign and pseudo- foreign tongues. He also wrote in several letters to Bill Townend that he thought of his books as stage plays, which means he was listening to his characters speaking as he wrote. In his first published book, The Pothunters (1902), we can listen to schoolboys: “That rotter, Reade, […] has been telling us that burglary chestnut of his all the morning. -

The PG Wodehouse Society

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 1 Revised December 2018 Books by P G Wodehouse The purpose of this information sheet is to provide a comprehensive list of the books written by P G Wodehouse. There is no agreement amongst commentators or aficionados as to how many he wrote, for the reasons explained below, and The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) does not express a view on this matter. Please note that the Society’s listing does not include titles of books which have appeared since Wodehouse’s death for which the Wodehouse Trustees did not give consent for publication. In some cases, this may be because the texts, for example short stories in a new compilation, are now in the public domain in the country of publication so that consent was not sought; in other cases, the publication maybe wholly unofficial, in breach of copyright law and not necessarily in a format in which Wodehouse would recognise. Reasons why there can be many legitimate views as to the number of his books include: 1 Several books, particularly collections of short stories, which were published in the United States differed in the minutiae of their contents from the nearest equivalent collection in the United Kingdom. 2 Some books have joint authorship with another person. 3 When referring to his output of fiction, it is necessary to exclude autobiographical and similar work, and collections of essays. 4 It is not uncommon for reports in the media to double-count his output, eg by misusing the term ‘novel’ to include short story collections, and accordingly referring to ‘more than 90 (or even 100) novels and 300 short stories’, when any total number of books approaching 100 will already have to include the collections of short stories.