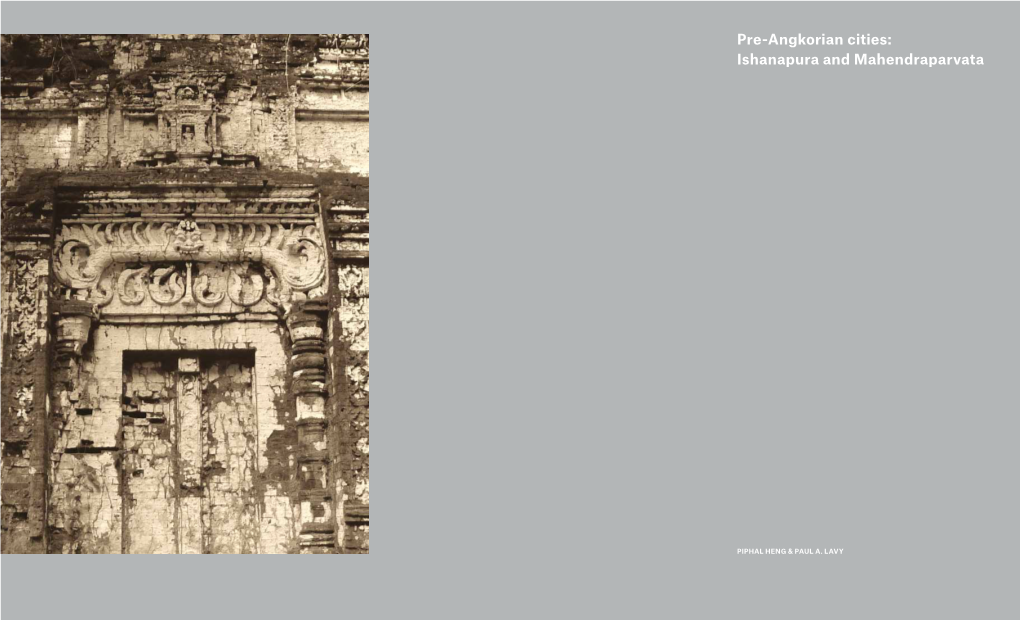

Pre-Angkorian Cities: Ishanapura and Mahendraparvata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power and Pragmatism in the Political Economy of Angkor

THESIS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARTS _________ DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY ____________ POWER AND PRAGMATISM IN THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ANGKOR EILEEN LUSTIG _________ UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2009 Figure 1 Location map 1 Abstract The relationship between the Angkorian Empire and its capital is important for understanding how this state was sustained. The empire’s political economy is studied by analysing data from Pre-Angkorian and Angkorian period inscriptions in aggregated form, in contrast to previous studies which relied mainly on detailed reading of the texts. The study is necessarily broad to overcome the constraints of having relatively few inscriptions which relate to a selected range of topics, and are partial in viewpoint. The success of the pre-modern Khmer state depended on: its long-established communication and trade links; mutual support of rulers and regional elites; decentralised administration through regional centres; its ability to produce or acquire a surplus of resources; and a network of temples as an ideological vehicle for state integration. The claim that there was a centrally controlled command economy or significant redistribution of resources, as for archaic, moneyless societies is difficult to justify. The mode of control varied between the core area and peripheral areas. Even though Angkor did not have money, it used a unit of account. Despite being an inland agrarian polity, the Khmer actively pursued foreign trade. There are indications of a structure, perhaps hierarchical, of linked deities and religious foundations helping to disseminate the state’s ideology. The establishment of these foundations was encouraged by gifts and privileges granted to elite supporters of the rulers. -

Virtual Sambor Prei Kuk: an Interactive Learning Tool

Virtual Sambor Prei Kuk: An Interactive Learning Tool Daniel MICHON Religious Studies, Claremont McKenna College Claremont, CA 91711 and Yehuda KALAY Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning The Technion - Israel Institute of Technology Haifa 32000, Israel ABSTRACT along the trade routes from its Indic origins into Southeast Asia—one of the great cultural assimilations in human history. MUVEs (Multi-User Virtual Environments) are a new media for researching the genesis and evolution of sites of cultural Much of this important work has, so far, remained the exclusive significance. MUVEs are able to model both the tangible and province of researchers, hidden from the general public who intangible heritage of a site, allowing the user to obtain a more might find it justifiably interesting. Further, the advent of dynamic understanding of the culture. This paper illustrates a immersive, interactive, Web-enabled, Multi-User Virtual cultural heritage project which captures and communicates the Environments (MUVEs) has provided us with the opportunity interplay of context (geography), content (architecture and to tell the story of Sambor Prei Kuk in a way that can help artifacts) and temporal activity (rituals and everyday life) visitors experience this remarkable cultural heritage as it might leading to a unique digital archive of the tangible and intangible have been in the seventh-eighth century CE. MUVEs are a new heritage of the temple complex at Sambor Prei Kuk, Cambodia, media vehicle that has the ability to communicate cultural circa seventh-eighth century CE. The MUVE is used to provide heritage experience in a way that is a cross between a platform which enables the experience of weaved tangible and filmmaking, video games, and architectural design. -

Temples Tour Final Lite

explore the ancient city of angkor Visiting the Angkor temples is of course a must. Whether you choose a Grand Circle tour or a lessdemanding visit, you will be treated to an unforgettable opportunity to witness the wonders of ancient Cambodian art and culture and to ponder the reasons for the rise and fall of this great Southeast Asian civili- zation. We have carefully created twelve itinearies to explore the wonders of Siem Reap Province including the must-do and also less famous but yet fascinating monuments and sites. + See the interactive map online : http://angkor.com.kh/ interactive-map/ 1. small circuit TOUR The “small tour” is a circuit to see the major tem- ples of the Ancient City of Angkor such as Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm and Bayon. We recommend you to be escorted by a tour guide to discover the story of this mysterious and fascinating civilization. For the most courageous, you can wake up early (depar- ture at 4:45am from the hotel) to see the sunrise. (It worth it!) Monuments & sites to visit MORNING: Prasats Kravan, Banteay Kdei, Ta Prohm, Takeo AFTERNOON: Prasats Elephant and Leper King Ter- race, Baphuon, Bayon, Angkor Thom South Gate, Angkor Wat Angkor Wat Banteay Srei 2. Grand circuit TOUR 3. phnom kulen The “grand tour” is also a circuit in the main Angkor The Phnom Kulen mountain range is located 48 km area but you will see further temples like Preah northwards from Angkor Wat. Its name means Khan, Preah Neak Pean to the Eastern Mebon and ‘mountain of the lychees’. -

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia

A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia NANCY H. DOWLING SCHOLARS FAMILIAR WITH SOUTHEAST ASIAN ART HISTORY are well aware of a confusing chronology for early Cambodian sculpture. One reason for this situa tion is obvious. For nearly fifty years, Cambodian art history has been wed to the work of George Coedes. Praised as the dean of Southeast Asian history, he was a member of an elite group of French scholars who worked in Cambodia for decades before World War II. In 1944, he wrote Histoire ancienne des hats hindouses d'Extreme-Orient, in which he established a chronological framework for early Southeast Asian history based on an interplay of Chinese texts and indigenous inscriptions. Most Southeast Asian historians readily admit that "his book remains the basic source for early South East Asian history, and while much recent re search, based upon new inscriptional evidence or re-readings, modifies some of Coedes' specific conclusions, the structure remains his" (Brown 1996: 3). Such a singular dependency on Coedes had a stifling effect on Cambodian art history. When Jean Boisselier, carrying on the work of Philippe Stern and Gilberte de Coral-Remusat, made a comprehensive attempt to set in order Cambodian sculpture, the French art historian fitted the works of art into Coedes' ready made chronology. Unfortunately, this all happened as if it were preferable to adjust Cambodian sculpture to a preconceived notion of history rather than ques tioning the model. In this way, some basic mistakes have been made, and these seriously affect the chronology and interpretation of early Cambodian sculpture. -

Angkor Highlight (04 Nights / 05 Days)

(Approved By Ministry of Tourism, Govt. of India) Angkor Highlight (04 Nights / 05 Days) Routing: Arrival Siem Reap - Rolous Group – Small Circuit – Angkor Wat – Grand Circuit - Banteay Srei – Tonle Sap Lake - Siem Reap Day 01 : Arrival Siem Reap (D) Welcome to Siem Reap, Cambodia! Upon arrival at Siem Reap Airport, greeting by our friendly tour guide, then you will be transferred direct to check in at hotel (room may ready at noon). This afternoon, we drive to visit the Angkor National Museum, learn about “the Legend Revealed” and see how the Khmer Empire has been established during the golden period. Continue to visit the Killing Fields at Wat Thmey, get to know some information about Khmer Rouge Regime or called the year of Zero (1975 – 1979) where over 2 million of Khmer people has been killed. Next visit to Preah Ang Check Preah Angkor, the secret place where local people go praying for good luck or safe journey. Day 02 : Rolous Group – Small Circuit (B, L) In the morning – we drive to explore the Roluos group. The Roluos group lies 15km(10 miles) southwest of Siem Reap and includes three temples - Bakong, Prah Ko and Lolei - dating from the late 9th century and corresponding to the ancient capital of Hariharalaya, from which the name of Lolei is derived. Remains include 3 well-preserved early temples that venerated the Hindu gods. The bas-reliefs are some of the earliest surviving examples of Khmer art. Modern-day villages surround the temples. In the afternoon, we visit small circuit including the unique brick sculptures of Prasat Kravan, the jungle intertwined Ta Prohm, made famous in Angelina Jolie’s Tomb Raider movie. -

Destination: Angkor Archaeological Park the Complete Temple Guide

Destination: Angkor Archaeological Park The Complete Temple Guide 1 The Temples of Angkor Ak Yom The earliest elements of this small brick and sandstone temple date from the pre-Angkorian 8th century. Scholars believe that the inscriptions indicate that the temple is dedicated to the Hindu 'god of the depths'. This is the earliest known example of the architectural design of the 'temple-mountain', which was to become the primary design for many of the Angkorian period temples including Angkor Wat. The temple is in a very poor condition. Angkor Thom Angkor Thom ("Great City") was the last and most enduring capital city of the Khmer empire. It was established in the late 12th century by King Jayavarman VII. The walled and moated royal city covers an area of 9 km², within which are located several monuments from earlier eras as well as those established by Jayavarman and his successors. At the centre of the city is Jayavarman's state temple, the Bayon, with the other major sites clustered around the Victory Square immediately to the north. Angkor Thom was established as the capital of Jayavarman VII's empire, and was the centre of his massive building programme. One inscription found in the city refers to Jayavarman as the groom and the city as his bride. Angkor Thom is accessible through 5 gates, one for each cardinal point, and the victory gate leading to the Royal Palace area. Angkor Wat Angkor Wat ("City of Temples"), the largest religious monument in the world, is a masterpiece of ancient architecture. The temple was built by the Khmer King Suryavarman II in the early 12th century as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Women in Cambodia – Analysing the Role and Influence of Women in Rural Cambodian Society with a Special Focus on Forming Religious Identity

WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY by URSULA WEKEMANN submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR D C SOMMER CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF R W NEL FEBRUARY 2016 1 ABSTRACT This study analyses the role and influence of rural Khmer women on their families and society, focusing on their formation of religious identity. Based on literature research, the role and influence of Khmer women is examined from the perspectives of history, the belief systems that shape Cambodian culture and thinking, and Cambodian social structure. The findings show that although very few Cambodian women are in high leadership positions, they do have considerable influence, particularly within the household and extended family. Along the lines of their natural relationships they have many opportunities to influence the formation of religious identity, through sharing their lives and faith in words and deeds with the people around them. A model based on Bible storying is proposed as a suitable strategy to strengthen the natural influence of rural Khmer women on forming religious identity and use it intentionally for the spreading of the gospel in Cambodia. KEY WORDS Women, Cambodia, rural Khmer, gender, social structure, family, religious formation, folk-Buddhism, evangelization. 2 Student number: 4899-167-8 I declare that WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -

Includes the Bayon, Angkor Thom, Siem Reap & Roluos Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANGKOR: INCLUDES THE BAYON, ANGKOR THOM, SIEM REAP & ROLUOS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Spooner | 104 pages | 07 Jul 2015 | Footprint Travel Guides | 9781910120224 | English | Bath, United Kingdom Angkor: Includes the Bayon, Angkor Thom, Siem Reap & Roluos PDF Book Suppose one day you woke up from a dream of wanting to visit one of the most magnificent temples in the world. As I mentioned other Khmer temples in the World heritage list, Vat Phou and Preah Vihear or even Phanomroong in the tentative list of Thailand are very inferior when compared with Angkor, if you see Angkor before you may have negative view on those sites, as I had one with Vat Phou after I saw Preah Vihear, so to avoid the problem and be more appreciated in Khmer art development, try to keep Angkor at the end of your trip, a highly recommendation. Bus ban at Angkor Wat Superior food and accomodations in the area. It was originally built as an Hindu temple to be later slowly converted into a Buddhist temple. Replica in Legoland : Legoland Malaysia. Its a huge area with a host of great temples, some smaller, some bigger, but all unique and incredible. Breaking with the tradition of the Khmer kings, and influenced perhaps by the concurrent rise of Vaisnavism in India, he dedicated the temple to Vishnu rather than to Siva. Retrieved In , Yasovarman ascended to the throne. Log into your account. Log into your account. Angkor Wat is an outstanding example of Khmer architecture, the so-called Angkor Wat style, for obvious reasons. If you do not have this information now, please contact the local activity operator 24 hours prior to the start of the tour with these details. -

A History of Cambodia Free Download

A HISTORY OF CAMBODIA FREE DOWNLOAD David P. Chandler | 384 pages | 02 Aug 2007 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780813343631 | English | Boulder, CO, United States A History of Cambodia (Third Edition) Simultaneous attacks around the perimeter of Phnom Penh pinned down Republican forces, while other CPK units overran fire bases controlling the vital lower Mekong resupply route. Early Funan was composed of loose communities, each with its own ruler, linked by a common culture and a shared economy of rice farming people in the hinterland and traders in the coastal towns, who were economically interdependent, A History of Cambodia surplus rice production found its way to the ports. Recording of the Royal Chronology discontinues with King Jayavarman IX Parameshwara or Jayavarma-Paramesvara — there exists not a single contemporary record of even a king's name for over years. Discount Codes. Retrieved 29 June Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. During his nearly forty years in power he becomes the A History of Cambodia prolific monument A History of Cambodia, who establishes the city of Angkor Thom with its central temple the Bayon. Neher Book Category Asia portal. Nov 25, Sarah rated it really liked it. Archived from the original PDF on 14 July From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Books by David P. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. My solution was to skim for time periods where I was most curious and to sort through for activities in specific parts of the country. The last Sanskrit inscription is datedand records the succession of Indrajayavarman by Jayavarman IX Parameshwara — His book on "A history of Cambodia" provides a comprehensive and insightful analysis and narratives on Cambodian history from the pre and post Angkor period until modern Cambodia. -

Reclamation and Regeneration of the Ancient Baray

RECLAMATION AND REGENERATION OF THE ANCIENT BARAY A Proposal for Phimai Historical Park Olmtong Ektanitphong December 2014 Submitted towards the fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Architecture Degree. School of Architecture University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Doctorate Project Committee Kazi K. Ashraf, Chairperson William R. Chapman, Committee Member Pornthum Thumwimol, Committee Member ACKNOWLEDMENTS I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Professor Kazi K. Ashraf, who has the attitude and the substance of a genius: he continually and convincingly a spirit of adventure in regard to research and the design, and excitement in regard to teaching. Without his guidance and persistent help this dissertation would not have been possible. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor William R. Chapman and Dr. Pornthum Thumwimol, whose work demonstrated to me that concern for archaeological aspects of Khmer and Thai culture. They supported me immensely throughout the period of my dissertation. Their valuable advice and discussions guided me to the end-result of this study. I highly appreciated for their generally being a good uncle and brother as well as a supervisor. In addition, a thank you to the director, archaeologists, academic officers and administration staff at Phimai Historical Park and at the Fine Arts Department of Thailand, who gave me such valuable information and discussion. Specially, thank you to Mr. Teerachat veerayuttanond, my supervisor during internship with The Fine Arts Department of Thailand, who first introduced me to Phimai Town and took me on the site survey at Phimai Town. Last but not least, I would like to thank University of Hawaii for giving me the opportunity for my study research and design. -

Figs. 7, 46 Pls. 15,16 Fig. 52 Fig. Figs. Fig. 24 Figs. 8, 12, Fig. 33

INDEX Ak Yorn, Prasat XIX, XXIl,46, 55 Borobudur, Java XXI, 27, 45, 46, 49, Anavatapa, lake 94 50, 51 Fig. 44 Andet, Prasat 44 Boulbet,Jean. 46 Andon, Prasat see Neak Ta Brahma 7 Angkor XIX, XXIII, XXVIII, 4, 5, 14, 20, 23, 24,44,48,50,54,55,62, Cakravartin 111 63, 64, 68, 72, 76, 78, 79, 81, 90, Ceylon 16, 17 96, 97, 98, 109, 110 Chaiya, Thailand 45 Angkor Thom 59, 81, 90, 94, 98, 99, Cham XXV, XXVII, 28, 45, 90, 99 105, 106, 107, 111 Chau Say Tevoda 30, 81, 90, 97 Angkor Wat XXIV, XXV, XXVI, Chola, dynasty 28 XXVII, XXVIII, XXIX, 4, 8, 12, Chou Ta-kuan (Zhou Daguan) 29, 79, 24, 26, 30, 31, 74, 78, 80, 83-89, 87, 101, 112 91, 98, 99, 100, 109, 111, 112 Chrei, Prasat 82, 90 Fig. 25 Figs. 28, 78,79 Pls. 31-33 Coedes, George 6, 18, 19, 22, 83 Argensola, d' XXVIII Aymonier, Etienne XXVIII Dagens, Bruno XXIII, 18, 46, 93 Damrei Krap, Prasat 28, 45, 4 7 Figs. Bakong XXI, 4, 11, 45, 50, 51, 53, 54, 43, 45 Pl. 14 55, 59, 65. Figs. 7, 46 Pls. 15,16 Dhrannindravarman I, King 7 Bakasei Chamkrong 29, 34, 54, 60, 63, Dieng, Java XVII, XX 66, 106. Fig. 52 Do Couto, Diego XXXVIII Baluchistan XVIII. Bantay Chmar XXVI, XXVII, 5, 12, 96, Elephant Terrace 78 Fig. 21 99. Bantay Kdei 28, 96, 98, 100. Bantay Samre 24. Filliozat, Jean 21 Bantay Srei 11, 15, 66-67, 69, 72 Fig.