Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices About Trachoma in Rural Communities of Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: Implications for Prevention and Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Role of Agricultural Education in the Development of Agriculture in Ethiopia Dean Alexander Elliott Iowa State College

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1957 Role of agricultural education in the development of agriculture in Ethiopia Dean Alexander Elliott Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons, and the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Elliott, Dean Alexander, "Role of agricultural education in the development of agriculture in Ethiopia " (1957). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1348. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1348 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROLE OP AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE IN ETHIOPIA by Dean Alexander Elliott A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Vocational Education Approved Signature was redacted for privacy. Charge of Major Work Signature was redacted for privacy. Hea Ma^ctr^partrnent Signature was redacted for privacy. Dé ah of Graduate Iowa State College 1957 il TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 COUNTRY AND PEOPLE .... ..... 5 History 5 Geography 16 People 30 Government 38 Ethiopian Orthodox Church lj.6 Transportation and Communication pif. NATIVE AGRICULTURE 63 Soils 71 Crops 85 Grassland and Pasture 109 Livestock 117 Land Tenure 135? GENERAL AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION 162 Organization and Administration 165 Teacher Supply and Teacher Education 175 Schools and Colleges 181}. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

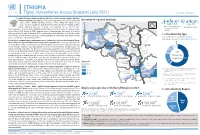

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

The Case of Alamata and Atsbi-Wonberta Woredas of Tigray Region

MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF POULTRY: THE CASE OF ALAMATA AND ATSBI-WONBERTA WOREDAS OF TIGRAY REGION M.Sc. Thesis Dawit Gebregziabher January 2010 Haramaya University MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF POULTRY: THE CASE OF ALAMATA AND ATSBI-WONBERTA WOREDAS OF TIGRAY REGION A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Agricultural Economics, School of Graduate Studies HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AGRICULTURE (AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS) BY Dawit Gebregziabher January 2010 Haramaya University APPROVAL SHEET SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES HARAMAYA UNIVERSITY As thesis research advisors, we here by certify that we have read and evaluated this thesis prepared, under our guidance, by Dawit Gebregziabher entitled “Market Chain Analysis of Poultry: the case of Alamata and Atsbi Wonberta Woredas of Tigray Region.” We recommend that it be submitted as fulfilling the thesis requirement. Berhanu Gebremedhin (PhD) __________________ ______________ Major Advisor Signature Date Dirk Hoekstra (Mr) __________________ _____________ Co-Advisor Signature Date As member of the Board of Examiners of the M.Sc Thesis Open Defense, we certify that we have read, evaluated the Thesis prepared by Dawit Gebregziabher Mekonen and examine the candidate. We recommend that the Thesis be accepted as fulfilling the Thesis requirement for the Degree of Master of Science in Agriculture (Agricultural Economics). DegnetAbebaw (PhD) __________________ _____________ Chair Person Signature Date Adem Kedir (Mr) __________________ _____________ Internal Examiner Signature Date Admasu Shbiru (PhD) __________________ _____________ External Examiner Signature Date ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis manuscript to my family for their moral and encouragement in the study period in particular and throughout my life in general. -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

20Th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ፳ኛ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ

20th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies ኛ ፳ የኢትዮጵያ ጥናት ጉባኤ Regional and Global Ethiopia – Interconnections and Identities 30 Sep. – 5 Oct. 2018 Mekelle University, Ethiopia Message by Prof. Dr. Fetien Abay, VPRCS, Mekelle University Mekelle University is proud to host the International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (ICES20), the most prestigious conference in social sciences and humanities related to the region. It is the first time that one of the younger universities of Ethiopia has got the opportunity to organize the conference by itself – following the great example set by the French team of the French Centre of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Abeba organizing the ICES in cooperation with Dire Dawa University in 2012, already then with great participation by Mekelle University academics and other younger universities of Ethiopia. We are grateful that we could accept the challenge, based on the set standards, in the new framework of very dynamic academic developments in Ethiopia. The international scene is also diversifying, not only the Ethiopian one, and this conference is a sign for it: As its theme says, Ethiopia is seen in its plural regional and global interconnections. In this sense it becomes even more international than before, as we see now the first time a strong participation from almost all neighboring countries, and other non-Western states, which will certainly contribute to new insights, add new perspectives and enrich the dialogue in international academia. The conference is also international in a new sense, as many academics working in one country are increasingly often nationals of other countries, as more and more academic life and progress anywhere lives from interconnections. -

Regreening of the Northern Ethiopian Mountains: Effects on Flooding and on Water Balance

PATRICK VAN DAMME THE ROLE OF TREE DOMESTICATION IN GREEN MARKET PRODUCT VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 129-147 REGREENING OF THE NORTHERN ETHIOPIAN MOUNTAINS: EFFECTS ON FLOODING AND ON WATER BALANCE Tesfaalem G. Asfaha (1,2), Michiel De Meyere (2), Amaury Frankl (2), Mitiku Haile (3), Jan Nyssen (2) (1) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia (2) Department of Geography, Ghent University, Belgium (3) Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, Ethiopia The hydro-geomorphology of mountain catchments is mainly determined by vegetation cover. This study was carried out to analyse the impact of vegetation cover dynamics on flooding and water balance in 11 steep (0.27-0.65 m m-1) catchments of the western Rift Valley escarpment of Northern Ethiopia, an area that experienced severe deforestation and degradation until the first half of the 1980s and considerable reforestation thereafter. Land cover change analysis was carried out using aerial photos (1936,1965 and 1986) and Google Earth imaging (2005 and 2014). Peak discharge heights of 332 events and the median diameter of the 10 coarsest bedload particles (Max10) moved in each event in three rainy seasons (2012-2014) were monitored. The result indicates a strong re- duction in flooding (R2 = 0.85, P<0.01) and bedload sediment supply (R2 = 0.58, P<0.05) with increas- ing vegetation cover. Overall, this study demonstrates that in reforesting steep tropical mountain catchments, magnitude of flooding, water balance and bedload movement is strongly determined by vegetation cover dynamics. -

Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES, SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Ethiopian Field Epidemiology Training Program(EFELTP) Compiled Body of Works in Field Epidemiology By Brhanu Adhana(Bsc) Cohort IX Submitted to School of Graduate Studies of Addis AbabUniversity in Partial Fulfilment for the Degree of Master Public Health in Field Epidemiology June 2019 Addis Ababa Ethiopia ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF HEALTHS CIENCES SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Ethiopian Field Epidemology Trainning Program(EFETP) Compiled Body Of Work In Field Epidemiology By Brhanu Adhana(Bsc) Sumitted to the School of Graduate Studies Addis Ababa University in Parial Fifulment for the Degree of Master of Public Health in Field Epidemiology JUNE 2019 ADDIS ABABA ETHIOPIA ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Ethiopian Field Epidemiology Training Program (EFETP) Compiled Body of Works in Field Epidemiology By Brhanu Adhana Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Public Health in Field Epidemiology Mentors Mr. Yimer Seid (MPH in Epi and Bio) Mr. Muluken Gizaw (MPH) June 2019 Addis Ababa ethiopia ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH Ethiopian Field Epidemiology Training Program (EFELP) Compiled Body of Work in Field Epidemiology By Brhanu Adhana(Bsc) Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfilment for the Degree of Master of Public Health in Field Epidemology Approval By Examiner Board --------------------------------- --------------------------- Chairman, School Graduate Committee ------------------------------------- ---------------------------- Advisor ----------------------------------- ----------------------------- Examiner ---------------------------------- ----------------------------- Examiner ------------------------------------------ ---------------------------------- Acknowledgement I would like to extend appreciation to my advisors Mr. Yimer Sied and Mr. -

Linking Poor Rural Households to Microfinance and Markets in Ethiopia

Linking Poor Rural Households to Microfinance and Markets in Ethiopia Baseline and Mid-term Assessment of the PSNP Plus Project in Raya Azebo November 2010 John Burns & Solomon Bogale Longitudinal Impact Study of the PSNP Plus Program Baseline Assessment in Raya Azebo Table of Contents SUMMARY 6 1. INTRODUCTION 8 1.1 PSNP PLUS PROJECT BACKGROUND 8 1.2 LINKING POOR RURAL HOUSEHOLDS TO MICROFINANCE AND MARKETS IN ETHIOPIA. 9 2 THE PSNP PLUS PROJECT 10 2.1 PSNP PLUS OVERVIEW 10 2.2 STUDY OVERVIEW 11 2.3 OVERVIEW OF PSNP PLUS PROJECT APPROACH IN RAYA AZEBO 12 2.3.1 STUDY AREA GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS 12 2.3.2 MICROFINANCE LINKAGE COMPONENT 12 2.3.3 VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATIONS 13 2.3.4 MARKET LINKAGE COMPONENT 14 2.3.5 IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES 17 2.4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS 18 3. ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY 19 3.1 STUDY APPROACH 19 3.2 OVERVIEW OF METHODS AND INDICATORS 19 3.3 INDICATOR SELECTION 20 3.4 SAMPLING 20 3.4.1 METHOD AND SIZE 20 3.4.2 STUDY LOCATIONS 21 3.5 DATA COLLECTION METHODS 22 3.5.1 HOUSEHOLD INTERVIEWS 22 3.5.2 FOCUS GROUP METHODS 22 3.6 PRE-TESTING 23 3.7 TRIANGULATION AND VALIDATION 23 3.8 DATA ANALYSIS 23 4 RESULTS 25 4.1 CONTEXTUALIZING PSNP PLUS 25 4.2 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND STATUS AT THE TIME OF THE ASSESSMENT 26 4.3 IMPACT OF THE DROUGHT IN 2009 28 4.4 COMMUNITY CHARACTERISTICS 29 4.5 INCOME AND EXPENDITURE 30 4.5.1 PROJECT DERIVED INCOME AND UTILIZATION 31 4.6 SAVINGS AND LOANS 33 4.6.1 PSNP PLUS VILLAGE SAVINGS GROUPS 34 4.7 ASSETS AND ASSET CHANGES 35 4.8. -

FEWS NET Ethiopia Trip Report Summary

FEWS NET Ethiopia Trip Report Summary Activity Name: Belg 2015 Mid-term WFP and FEWS NET Joint assessment Reported by: Zerihun Mekuria (FEWS NET) and Muluye Meresa (WFP_Mekelle), Dates of travel: 20 to 22 April 2015 Area Visited: Ofla, Raya Alamata and Raya Azebo Woredas in South Tigray zones Reporting date: 05 May 2015 Highlights of the findings: Despite very few shower rains in mid-January, the onset of February to May Belg 2015 rains delayed by more than six weeks in mid-March and most Belg receiving areas received four to five days rains with amount ranging low to heavy. It has remained drier and warmer since 3rd decade of March for more than one month. Most planting has been carried out in mid-March except in few pocket areas in the highlands that has planted in January. About 54% of the normal Belg area has been covered with Belg crops. Planted crops are at very vegetative stage with significant seeds remained aborted in the highlands. While in the lowlands nearly entire field planted with crop is dried up or wilted. Dryness in the Belg season has also affected the land preparation and planting for long cycle sorghum. Although the planting window for sorghum not yet over, prolonged dryness will likely lead farmers to opt for planting low yielding sorghum variety. Average Meher 2014 production has improved livestock feed availability. The crop residue reserve from the Meher harvest is not yet exhausted. Water availability for livestock is normal except in five to seven kebeles in Raya Azebo woreda that has faced some water shortages for livestock. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Agricultural Sciences SEED AID, SMALLHOLDERS, AND THE DEVELOPMENTAL STATE: A MIXED METHODS ANALYSIS OF EMERGENCY RELIEF PROGRAMS IN ETHIOPIA A Dissertation in Rural Sociology & International Agriculture and Development by Christian R. Man © 2018 Christian R. Man Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 The dissertation of Christian R. Man was reviewed and approved* by the following: Leland Glenna Professor of Rural Sociology and Science, Technology, and Society Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian Thiede Assistant Professor of Rural Sociology, Sociology, and Demography Carolyn Sachs Professor Emerita of Rural Sociology Karl Zimmerer Professor of Environment and Society Department of Geography Kathryn J. Brasier Professor of Rural Sociology Director of Graduate Studies in Rural Sociology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT In 2015, El Niño induced the worst drought Ethiopia had seen in fifty years. The resulting crop failures left as many as eighteen million people in need of aid, with one-third of the country’s woredas classified as facing dire food insecurity. Tens of millions of dollars in foreign aid poured into the country in response. A portion of this aid was given as seed to smallholders. Drawing on quantitative and qualitative data collected with farmers in four regions of Ethiopia in 2016 following the aid distributions, this dissertation analyzes how the Ethiopian state and Ethiopian smallholders respectively utilize seed aid. I suggest these utilization strategies coincide, that they serve different ends, and that, together, they illustrate the complex effects of emergency response. -

SITUATION ANALYSIS of CHILDREN and WOMEN: Tigray Region

SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: Tigray Region SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: Tigray Region This briefing note covers several issues related to child well-being in Tigray Regional State. It builds on existing research and the inputs of UNICEF Ethiopia sections and partners.1 It follows the structure of the Template Outline for Regional Situation Analyses. 1Most of the data included in this briefing note comes from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), Household Consumption and Expenditure Survey (HCES), Education Statistics Annual Abstract (ESAA) and Welfare Monitoring Survey (WMS) so that a valid comparison can be made with the other regions of Ethiopia. SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: TIGRAY REGION 4 1 THE DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT The northern and mountainous region of Tigray has an estimated population of 5.4 million people, of which approximately 13 per cent are under 5 years old and 43 per cent is under 18 years of age. This makes Tigray the fifth most populous region of Ethiopia. Tigray has a relatively high percentage of female-headed households, at 34 per cent in 2018 versus a national rate of 25 per cent in 2016. Three out of four Tigrayans live in rural areas, and most depend on agriculture (mainly subsistence crop farming).4 Urbanization is an emerging priority, as many new towns are created, and existing towns expand. Urbanization in Tigray is referred to as ‘aggressive’, with an annual rate of 4.6 per cent in the Tigray Socio-Economic Baseline Survey Report (2018).5 The annual urban growth