The World Health Organization Classification of Hematological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Development of the ICD

History of the development of the ICD 1. Early history Sir George Knibbs, the eminent Australian statistician, credited François Bossier de Lacroix (1706-1777), better known as Sauvages, with the first attempt to classify diseases systematically (10). Sauvages' comprehensive treatise was published under the title Nosologia methodica. A contemporary of Sauvages was the great methodologist Linnaeus (1707-1778), one of whose treatises was entitled Genera morborum. At the beginning of the 19th century, the classification of disease in most general use was one by William Cullen (1710-1790), of Edinburgh, which was published in 1785 under the title Synopsis nosologiae methodicae. For all practical purposes, however, the statistical study of disease began a century earlier with the work of John Graunt on the London Bills of Mortality. The kind of classification envisaged by this pioneer is exemplified by his attempt to estimate the proportion of liveborn children who died before reaching the age of six years, no records of age at death being available. He took all deaths classed as thrush, convulsions, rickets, teeth and worms, abortives, chrysomes, infants, livergrown, and overlaid and added to them half the deaths classed as smallpox, swinepox, measles, and worms without convulsions. Despite the crudity of this classification his estimate of a 36 % mortality before the age of six years appears from later evidence to have been a good one. While three centuries have contributed something to the scientific accuracy of disease classification, there are many who doubt the usefulness of attempts to compile statistics of disease, or even causes of death, because of the difficulties of classification. -

A Brief Evaluation and Image Formation of Pediatrics Nutritional Forum in Opinion Sector Disouja Wills* Nutritonal Sciences, Christian Universita Degli Studo, Italy

d Pediatr Wills, Matern Pediatr Nutr 2016, 2:2 an ic l N a u n t DOI: 10.4172/2472-1182.1000113 r r e i t t i o Maternal and Pediatric a n M ISSN: 2472-1182 Nutrition ShortResearch Commentary Article OpenOpen Access Access A Brief Evaluation and Image formation of Pediatrics Nutritional Forum in Opinion Sector Disouja Wills* Nutritonal Sciences, Christian Universita degli studo, Italy Abstract Severe most and one of the main global threat is Nutritional disorders to backward countries, with respect to this issue WHO involved and trying to overcome this issue with the Co-ordination of INF and BNF. International Nutrition Foundation and British Nutrition Foundation, development in weight gain through proper nutrition and proper immune mechanism in the kids is their main role to eradicate and overcome nutritional problems in world. Keywords: INF; BNF; Malnutrition; Merasmus; Rickets; Weight loss; Precautions to Avoid Nutrition Deficiency in Paediatric health issue Paediatrics Introduction Respective disease having respective deficiency dis order but in the case of nutritional diseases. Proper nutrition is the only thing to cure In the mankind a respective one health and weight gain is fully nutritional disorders. Providing sufficient diet like fish, meat, egg, milk based on perfect nutritional intake which he is having daily, poor diet to malnourished kids and consuming beef, fish liver oil, sheep meat, will show the improper impact and injury to the some of the systems boiled eggs from the age of 3 itself (Tables 1 and 2). in the body, total health also in some times. Blindness, Scurvy, Rickets will be caused by nutritional deficiency disorders only, mainly in kids. -

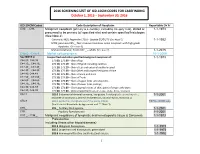

2016 SCREENING LIST of ICD-10CM CODES for CASEFINDING October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016

2016 SCREENING LIST OF ICD-10CM CODES FOR CASEFINDING October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016 ICD-10-CM Codes Code Description of Neoplasm Reportable Dx Yr C00._- C96._ Malignant neoplasm (primary & secondary; excluding category C44), stated or 1-1-1973 presumed to be primary (of specified site) and certain specified histologies (See Note 2) Carcinoid, NOS; Appendix C18.0 - Update 01/01/15 (See Note 5) 1-1-1992 MCN; pancreas C25._; Non-invasive mucinous cystic neoplasm with high grade dysplasia. (See note 6) Mature teratoma; Testis C62._ – adults (See note 7) 1-1-2015 C4a.0_-C4a.9_ Merkel cell carcinoma 10-1-2009 See NOTE 4 Unspecified and other specified malignant neoplasm of : 1-1-1973 C44.00.-C44.09 173.00, 173.09 – Skin of Lip C44.10_, C44.19_ 173.10, 173.19 – Skin of Eyelid including canthus C44.20_, C44.29_ 173. 20, 173.29 – Skin of Ear and external auditory canal C44.30_, C44.39_ 173.30, 173.39 – Skin Other and unspecified parts of face C44.40, C44.49 173. 40, 173.49 – Skin of Scalp and neck C44.50_, C44.59_ 173.50, 173.59 – Skin of Trunk C44.60_, C44.69_ 173. 60, 173.69 – Skin of Upper limb and shoulder, C44.70_, C44.79_ 173.70, 173.79 – Skin of Lower limb and hip; C44.80, C44.89 173.80, 173.89 – Overlapping lesions of skin, point of origin unknown; C44.90, C44.99 173.90, 173.99 - Sites unspecified (excludes Labia, Vulva, Penis, Scrotum) C54.1 182.0 Endometrial stromal sarcoma, low grade; Endolymphatic stromal myosis ; 1-1-2001 Endometrial stromatosis, Stromal endometriosis, Stromal myosis, NOS (C54.1) C56.9 183.0 Borderline malignancies -

Disease Discovery Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms

From www.bloodjournal.org by on December 4, 2008. For personal use only. 2008 112: 4384-4399 doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-077982 Classification of lymphoid neoplasms: the microscope as a tool for disease discovery Elaine S. Jaffe, Nancy Lee Harris, Harald Stein and Peter G. Isaacson Updated information and services can be found at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/full/112/12/4384 Articles on similar topics may be found in the following Blood collections: Neoplasia (4200 articles) Free Research Articles (544 articles) ASH 50th Anniversary Reviews (32 articles) Clinical Trials and Observations (2473 articles) Information about reproducing this article in parts or in its entirety may be found online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/misc/rights.dtl#repub_requests Information about ordering reprints may be found online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/misc/rights.dtl#reprints Information about subscriptions and ASH membership may be found online at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/subscriptions/index.dtl Blood (print ISSN 0006-4971, online ISSN 1528-0020), is published semimonthly by the American Society of Hematology, 1900 M St, NW, Suite 200, Washington DC 20036. Copyright 2007 by The American Society of Hematology; all rights reserved. From www.bloodjournal.org by on December 4, 2008. For personal use only. ASH 50th anniversary review Classification of lymphoid neoplasms: the microscope as a tool for disease discovery Elaine S. Jaffe,1 Nancy Lee Harris,2 Harald Stein,3 and Peter -

Scientific and Medical Aspects of Apheresis: Issues and Evidence 3 ● Scientific and Medical Aspects of Apheresis: Issues and Evidence

3 Scientific and Medical Aspects of Apheresis: Issues and Evidence 3 ● Scientific and Medical Aspects of Apheresis: Issues and Evidence Various types of apheresis procedures have paucity of high-quality research, conclusions been performed on a clinical basis for many years, about the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of but the number of patients and types of diseases apheresis are necessarily limited, although some treated have risen significantly in the last 5 years. tentative conclusions and directions for treatment This increase is partially due to increased under- can be discerned. standing of the disease and partially due to engi- The present chapter analyzes the methodolog- neering advances in equipment technologies. By ical problems in conducting apheresis research and almost any standard, treatment by apheresis is still examines available evidence of the safety, ef- in relatively early stages of development—there ficacy, and effectiveness of apheresis. Following are no ideal protocols based on a thorough un- a discussion of methodological issues, several derstanding of reasons for its efficacy. Never- major reviews of apheresis research will be sum- theless, there is an increasing flow of clinical data, marized and evaluated. This chapter will further sometimes describing dramatic patient improve- include the findings of a primary literature review ment, supporting the view that apheresis is a and assessment of apheresis in the treatment of rapidly emerging technology with significant three diseases—namely, hemolytic uremic syn- promise (117). Such evidence of treatment effec- drome, acquired Factor-VIII inhibitor, and Guil- tiveness’ is even today, however, often based on lain-Barré syndrome— where preliminary reports unsystematically collected data. -

Romidepsin (Istodax) Reference Number: ERX.SPA

Clinical Policy: Romidepsin (Istodax) Reference Number: ERX.SPA. 267 Effective Date: 12.01.18 Last Review Date: 11.20 Line of Business: Commercial, Medicaid Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Romidepsin (Istodax®) is a histone deacetylase inhibitor. FDA Approved Indication(s) Istodax is indicated for the treatment of: • Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) in adult patients who have received at least one prior systemic therapy; • Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) in adult patients who have received at least one prior therapy. o This indication is approved under accelerated approval based on response rate. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials. Policy/Criteria Provider must submit documentation (such as office chart notes, lab results or other clinical information) supporting that member has met all approval criteria. Health plan approved formularies should be reviewed for all coverage determinations. Requirements to use preferred alternative agents apply only when such requirements align with the health plan approved formulary. It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Envolve Pharmacy Solutions™ that Istodax and romidepsin injection solution are medically necessary when the following criteria are met: I. Initial Approval Criteria A. Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (must meet all): 1. Diagnosis of CTCL (see Appendix D for examples of CTCL subtypes); 2. Prescribed by or in consultation with an oncologist or hematologist; 3. Age ≥ 18 years; 4. Request meets one of the following (a or b):* a. Dose does not exceed 14 mg/m2 for three days of a 28-day cycle; b. -

Osteoporosis in Premenopausal Women: a Clinical Narrative Review by the ECTS and the IOF

This is a repository copy of Osteoporosis in premenopausal women: a clinical narrative review by the ECTS and the IOF. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/162028/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Pepe, J., Body, J.-J., Hadji, P. et al. (8 more authors) (2020) Osteoporosis in premenopausal women: a clinical narrative review by the ECTS and the IOF. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. ISSN 0021-972X https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa306 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism following peer review. The version of record Jessica Pepe, Jean-Jacques Body, Peyman Hadji, Eugene McCloskey, Christian Meier, Barbara Obermayer-Pietsch, Andrea Palermo, Elena Tsourdi, M Carola Zillikens, Bente Langdahl, Serge Ferrari, Osteoporosis in premenopausal women: a clinical narrative review by the ECTS and the IOF, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, dgaa306 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa306 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

In the Prevention of Occupational Diseases 94 7.1 Introduction

Report on the current situation in relation to occupational diseases' systems in EU Member States and EFTA/EEA countries, in particular relative to Commission Recommendation 2003/670/EC concerning the European Schedule of Occupational Diseases and gathering of data on relevant related aspects ‘Report on the current situation in relation to occupational diseases’ systems in EU Member States and EFTA/EEA countries, in particular relative to Commission Recommendation 2003/670/EC concerning the European Schedule of Occupational Diseases and gathering of data on relevant related aspects’ Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Foreword .................................................................................................... 4 1.2 The burden of occupational diseases ......................................................... 4 1.3 Recommendation 2003/670/EC .................................................................. 6 1.4 The EU context .......................................................................................... 9 1.5 Information notices on occupational diseases, a guide to diagnosis .................................................................................................. 11 1.6 Objectives of the project ........................................................................... 11 1.7 Methodology and sources ........................................................................ 12 1.8 Structure of the report .............................................................................. 15 2 Developments -

A Retrospective Chart Review Examining the Clinical Utility of Family Health History

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence The Joan H. Marks Graduate Program in Human Genetics Theses Human Genetics 5-2017 A Retrospective Chart Review Examining the Clinical Utility of Family Health History Katherine Dao Sarah Lawrence College Julia Russo Sarah Lawrence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/genetics_etd Part of the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Dao, Katherine and Russo, Julia, "A Retrospective Chart Review Examining the Clinical Utility of Family Health History" (2017). Human Genetics Theses. 33. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/genetics_etd/33 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the The Joan H. Marks Graduate Program in Human Genetics at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Genetics Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Katherine Dao and Julia Russo A Retrospective Chart Review Examining the Clinical Utility of Family Health History Authors: Katherine Dao, Julia Russo, Jennifer L. Garbarini, Sheila C. Johal, Shannon Wieloch Submitted in partial completion of the Master of Science Degree at Sarah Lawrence College, May 2017 1/34 Katherine Dao and Julia Russo Abstract Family health history (FHH) is a simple and cost-effective clinical tool widely used by genetic professionals. Although the value of FHH for assessing personal and familial health and reproductive risk within a prenatal population has been demonstrated in past studies, its utility within a genetic carrier screening population has not been evaluated. The purpose of this study was to examine the utility of FHH as a clinical screening tool and explore the general outcomes of full FHH evaluations within an expanded carrier screening (ECS) population. -

European Conference on Rare Diseases

EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON RARE DISEASES Luxembourg 21-22 June 2005 EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON RARE DISEASES Copyright 2005 © Eurordis For more information: www.eurordis.org Webcast of the conference and abstracts: www.rare-luxembourg2005.org TABLE OF CONTENT_3 ------------------------------------------------- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CREDITS A specialised clinic for Rare Diseases : the RD TABLE OF CONTENTS Outpatient’s Clinic (RDOC) in Italy …………… 48 ------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------- 4 / RARE, BUT EXISTING The organisers particularly wish to thank ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND CREDITS 4.1 No code, no name, no existence …………… 49 ------------------------------------------------- the following persons/organisations/companies 4.2 Why do we need to code rare diseases? … 50 PROGRAMME COMMITTEE for their role : ------------------------------------------------- Members of the Programme Committee ……… 6 5 / RESEARCH AND CARE Conference Programme …………………………… 7 …… HER ROYAL HIGHNESS THE GRAND DUCHESS OF LUXEMBOURG Key features of the conference …………………… 12 5.1 Research for Rare Diseases in the EU 54 • Participants ……………………………………… 12 5.2 Fighting the fragmentation of research …… 55 A multi-disciplinary approach ………………… 55 THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION Funding of the conference ……………………… 14 Transfer of academic research towards • ------------------------------------------------- industrial development ………………………… 60 THE GOVERNEMENT OF LUXEMBOURG Speakers ……………………………………………… 16 Strengthening cooperation between academia -

Heberden Society

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.25.1.86-b on 1 January 1966. Downloaded from Ann. rheum. Dis. (1966), 25, 86 HEBERDEN SOCIETY OFFICERS, 1966 Junior Hon. Secretary: Dr. J. A. Cosh President: Dr. Oswald Savage Hon. Librarian: Dr. W. S. C. Copeman President-Elect: Dr. J. J. R. Duthie PROGRAMME OF MEETINGS, 1966 March 25: Clinical Meeting, Rheumatism Research Hon. Treasurer: Wing, Birmingham. May 20: Meeting at Harrogate. Dr. F. Dudley Hart October 7: Heberden Round conducted by Dr. R. M. Mason at the London Hospital. Senior Hon. Secretary: November 18: Heberden Oration by Prof. E. G. L. Dr. C. F. Hawkins, Bywaters and Annual General Meeting at the Wellcome Rheumatism Research Wing, Foundation, London. Annual Dinner at the Royal Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, 15 College of Physicians, Regents Park, London. by copyright. DR. HUGH CLEGG Dr. Hugh Clegg retired from the Editorship of the in 1945, soon after the war. He has always exerted an British Medical Journal at the beginning of this year and active influence and rheumatology in Great Britain owes so also from the Editorial Board of the Annals. It was him much. due to his foresight and help that our Journal was The Editor and members of the Editorial Committee adopted by the British Medical Association as one of and Board will miss his wise guidance, but wish him well their quarterly specialist journals which he inaugurated in his retirement. http://ard.bmj.com/ LIGUE INTERNATIONALE CONTRE LE RHUMATISME XI International Congress of Rheumatology, Argentina, 1965 on September 28, 2021 by guest. -

Environmental Nutrition: Redefining Healthy Food

Environmental Nutrition Redefining Healthy Food in the Health Care Sector ABSTRACT Healthy food cannot be defined by nutritional quality alone. It is the end result of a food system that conserves and renews natural resources, advances social justice and animal welfare, builds community wealth, and fulfills the food and nutrition needs of all eaters now and into the future. This paper presents scientific data supporting this environmental nutrition approach, which expands the definition of healthy food beyond measurable food components such as calories, vitamins, and fats, to include the public health impacts of social, economic, and environmental factors related to the entire food system. Adopting this broader understanding of what is needed to make healthy food shifts our focus from personal responsibility for eating a healthy diet to our collective social responsibility for creating a healthy, sustainable food system. We examine two important nutrition issues, obesity and meat consumption, to illustrate why the production of food is equally as important to consider in conversations about nutrition as the consumption of food. The health care sector has the opportunity to harness its expertise and purchasing power to put an environmental nutrition approach into action and to make food a fundamental part of prevention-based health care. but that it must come from a food system that conserves and I. Using an Environmental renews natural resources, advances social justice and animal welfare, builds community wealth, and fulfills the food and Nutrition Approach to nutrition needs of all eaters now and into the future.i Define Healthy Food This definition of healthy food can be understood as an environmental nutrition approach.