SPARLING-THESIS-2021.Pdf (1.469Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Strengthening Canadian Engagement in Eastern Europe and Central Asia

STRENGTHENING CANADIAN ENGAGEMENT IN EASTERN EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA UZBEKISTAN 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Hon. Robert D. Nault Chair NOVEMBER 2017 Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. -

Canada, the Us and Cuba

CANADA, THE US AND CUBA CANADA, THE US AND CUBA HELMS-BURTON AND ITS AFTERMATH Edited by Heather N. Nicol Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Canada, the US and Cuba : Helms-Burton and its aftermath (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 21) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88911-884-1 1. United States. Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996. 2. Canada – Foreign relations – Cuba. 3. Cuba – Foreign relations – Canada. 4. Canada – Foreign relations – United States. 5. United States – Foreign relations – Canada. 6. United States – Foreign relations – Cuba. 7. Cuba – Foreign relations – United States. I. Nicol, Heather N. (Heather Nora), 1953- . II. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations. III. Series. FC602.C335 1999 327.71 C99-932101-3 F1034.2.C318 1999 © Copyright 1999 The Martello Papers The Queen’s University Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the twenty-first in its series of security studies, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to de- fend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues rele- vant to contemporary international strategic relations. This volume presents a collection of insightful essays on the often uneasy but always interesting United States-Cuba-Canada triangle. Seemingly a relic of the Cold War, it is a topic that, as editor Heather Nicol observes, “is always with us,” and indeed is likely to be of greater concern as the post-Cold War era enters its second decade. -

Dealing with Crisis

Briefing on the New Parliament December 12, 2019 CONFIDENTIAL – FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Regional Seat 8 6 ON largely Flip from NDP to Distribution static 33 36 Bloc Liberals pushed out 10 32 Minor changes in Battleground B.C. 16 Liberals lose the Maritimes Goodale 1 12 1 1 2 80 10 1 1 79 1 14 11 3 1 5 4 10 17 40 35 29 33 32 15 21 26 17 11 4 8 4 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 BC AB MB/SK ON QC AC Other 2 Seats in the House Other *As of December 5, 2019 3 Challenges & opportunities of minority government 4 Minority Parliament In a minority government, Trudeau and the Liberals face a unique set of challenges • Stable, for now • Campaign driven by consumer issues continues 5 Minority Parliament • Volatile and highly partisan • Scaled back agenda • The budget is key • Regulation instead of legislation • Advocacy more complicated • House committee wild cards • “Weaponized” Private Members’ Bills (PMBs) 6 Kitchen Table Issues and Other Priorities • Taxes • Affordability • Cost of Living • Healthcare Costs • Deficits • Climate Change • Indigenous Issues • Gender Equality 7 National Unity Prairies and the West Québéc 8 Federal Fiscal Outlook • Parliamentary Budget Officer’s most recent forecast has downgraded predicted growth for the economy • The Liberal platform costing projected adding $31.5 billion in new debt over the next four years 9 The Conservatives • Campaigned on cutting regulatory burden, review of “corporate welfare” • Mr. Scheer called a special caucus meeting on December 12 where he announced he was stepping -

Core 1..186 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 141 Ï NUMBER 051 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, September 22, 2006 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 3121 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, September 22, 2006 The House met at 11 a.m. Foreign Affairs, the actions of the minority Conservative govern- ment are causing the Canadian business community to miss the boat when it comes to trade and investment in China. Prayers The Canadian Chamber of Commerce is calling on the Conservative minority government to bolster Canadian trade and investment in China and encourage Chinese companies to invest in STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Canada. Business leaders are not alone in their desire for a stronger Ï (1100) economic relationship with China. The Asia-Pacific Foundation [English] released an opinion poll last week where Canadians named China, not the United States, as the most important potential export market CANADIAN FORCES for Canada. Mr. Pierre Lemieux (Glengarry—Prescott—Russell, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I recently met with a special family in my riding. The The Conservatives' actions are being noticed by the Chinese Spence family has a long, proud tradition of military service going government, which recently shut down negotiations to grant Canada back several generations. The father, Rick Spence, is a 27 year approved destination status, effectively killing a multi-million dollar veteran who serves in our Canadian air force. opportunity to allow Chinese tourists to visit Canada. His son, Private Michael Spence, is a member of the 1st Battalion China's ambassador has felt the need to say that we need mutual of the Royal Canadian Regiment. -

Evidence of the Special Committee on the COVID

43rd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Special Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic EVIDENCE NUMBER 019 Tuesday, June 9, 2020 Chair: The Honourable Anthony Rota 1 Special Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic Tuesday, June 9, 2020 ● (1200) Mr. Paul Manly (Nanaimo—Ladysmith, GP): Thank you, [Translation] Madam Chair. The Acting Chair (Mrs. Alexandra Mendès (Brossard— It's an honour to present a petition for the residents and con‐ Saint-Lambert, Lib.)): I now call this meeting to order. stituents of Nanaimo—Ladysmith. Welcome to the 19th meeting of the Special Committee on the Yesterday was World Oceans Day. This petition calls upon the COVID-19 Pandemic. House of Commons to establish a permanent ban on crude oil [English] tankers on the west coast of Canada to protect B.C.'s fisheries, tourism, coastal communities and the natural ecosystems forever. I remind all members that in order to avoid issues with sound, members participating in person should not also be connected to the Thank you. video conference. For those of you who are joining via video con‐ ference, I would like to remind you that when speaking you should The Acting Chair (Mrs. Alexandra Mendès): Thank you very be on the same channel as the language you are speaking. much. [Translation] We now go to Mrs. Jansen. As usual, please address your remarks to the chair, and I will re‐ Mrs. Tamara Jansen (Cloverdale—Langley City, CPC): mind everyone that today's proceedings are televised. Thank you, Madam Chair. We will now proceed to ministerial announcements. I'm pleased to rise today to table a petition concerning con‐ [English] science rights for palliative care providers, organizations and all health care professionals. -

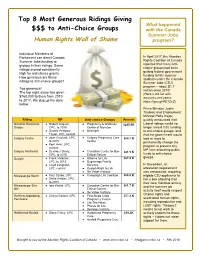

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving What happened $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups with the Canada Summer Jobs Human Rights Wall of Shame program? Individual Members of Parliament can direct Canada In April 2017, the Abortion Summer Jobs funding to Rights Coalition of Canada groups in their ridings. Some reported that many anti- ridings scored consistently choice groups had been getting federal government high for anti-choice grants. funding to hire summer How generous are these students under the Canada ridings to anti-choice groups? Summer Jobs (CSJ) program – about $1.7 Too generous! million since 2010! The top eight alone has given (Here’s the list with $760,000 to them from 2010 amounts and years: to 2017. We dug up the data https://goo.gl/4C1ZsC) below. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Employment Minister Patty Hajdu Riding MP Anti-choice Groups Amount quickly announced that Moncton-Riverview- ● Robert Goguen, ● Pregnancy & Wellness $285.6K Liberal ridings would no Dieppe CPC, to 2015 Centre of Moncton longer award CSJ funding ● Ginette Petitpas- ● Birthright to anti-choice groups, and Taylor, LPC, current that the government would Calgary Centre ● Joan Crockatt, CPC, ● Calgary Pregnancy Care $84.7 K look at ways to to 2015 Centre permanently change the ● Kent Hehr, LPC, program to prevent any current MP from allocating public Calgary Northeast ● Devinder Shory, ● Canadian Centre for Bio- $81.5 K CPC, to 2015 Ethical Reform funds to anti-choice groups. Guelph ● Frank Valeriote, ● Alliance for Life $67.9 K LPC, to 2015 ● Beginnings Family -

R114: Council Remuneration and Expense Payments for 2008

Corporate NO: R114 Report COUNCIL DATE: June 29, 2009 REGULAR COUNCIL TO: Mayor & Council DATE: June 29, 2009 FROM: General Manager, Finance & Technology FILE: 0560-01 SUBJECT: Council Remuneration and Expense Payments for 2008 RECOMMENDATION The Finance and Technology Department recommends that Council receive as information the attached Appendices A to K, which document remuneration and expenses for City Council members for the year 2008. DISCUSSION Section 168 of the Community Charter requires that a report be presented to Council at least once a year, that separately lists for each council member the following information: The total amount of remuneration paid to each council member for the discharge of the duties of office including any amount specified as an expense; The total amount of expense payments for each council member when representing the City, engaging in City business or attending a meeting, course or convention; The total amount of any benefits including insurance policies and policies for medical or dental services provided to each council member or council member’s dependants, and The details of any municipal contract with council members as reported under Section 107 of the Community Charter. The attached Appendices A to K satisfy the above listed requirements for the year 2008. Vivienne Wilke, CGA General Manager, Finance & Technology Attachments APPENDIX A CITY OF SURREY SUMMARY OF MAYOR & COUNCIL REMUNERATION AND EXPENSES JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2008 Remunerations & Event Expenses Indemnities Vehicle All owance -

Discerning Claim Making: Political Representation of Indo-Canadians by Canadian Political Parties

Discerning Claim Making: Political Representation of Indo-Canadians by Canadian Political Parties by Anju Gill B.A., University of the Fraser Valley, 2012 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Anju Gill 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2017 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Anju Gill Degree: Master of Arts Title: Discerning Claim Making: Political Representation of Indo-Canadians by Canadian Political Parties Examining Committee: Chair: Tsuyoshi Kawasaki Associate Professor Eline de Rooij Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor Mark Pickup Supervisor Associate Professor Genevieve Fuji Johnson Internal/External Examiner Professor Date Defended/Approved: September 21, 2017 ii Abstract The targeting of people of colour by political parties during election campaigns is often described in the media as “wooing” or “courting.” How parties engage or “woo” non- whites is not fully understood. Theories on representation provide a framework for the systematic analysis of the types of representation claims made by political actors. I expand on the political proximity approach—which suggests that public office seekers make more substantive than symbolic claims to their partisans than to non-aligned voters—by arguing that Canadian political parties view mainstream voters as their typical constituents and visible minorities, such as Indo-Canadians, as peripheral constituents. Consequently, campaign messages targeted at mainstream voters include more substantive claims than messages targeted at non-white voters. -

NDP Response - Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS)

NDP Response - Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) Establishing Child-Friendly Pharmacare 1. What will your party do to ensure that all children and youth have equitable access to safe, effective and affordable prescription drugs? An NDP government will implement a comprehensive, public universal pharmacare system so that every Canadian, including children, has access to the medication they need at no cost. 2. What measures will your party take to ensure that Canada has a national drug formulary and compounding registry that is appropriate for the unique needs of paediatric patients? An NDP government would ensure that decisions over what drugs to cover in the national formulary would be made by an arm’s-length body that would negotiate with drug companies. This would ensure that the needs of Canadians – from paediatric to geriatric – are considered. The NDP will work with paediatricians, health professionals, and other stakeholders to ensure that the formulary meets the needs of Canadians and that children and youth have access to effective and safe medication that will work for them. 3. How will your party strengthen Canada’s regulatory system to increase the availability and accessibility of safe paediatric medications and child- friendly formulations? The best way to increase the availability and accessibility of safe paediatric medications and child-friendly formulations is by establishing a comprehensive, national public pharmacare system because it gives Canada the strongest negotiating power with pharmaceutical companies. An NDP government will work with patients, caregivers, health professionals, and pharmaceutical companies to ensure that the best interest of Canadians will not continue to be adversely impacted by the long-awaited need for universal pharmacare. -

Parliamentary Internship Programme 2020-21 Annual Report

Parliamentary Internship Programme 2020-21 Annual Report Annual General Meeting Canadian Political Science Association June 11, 2021 Dr. Paul Thomas Director Web: pip-psp.org Twitter: @PIP_PSP Instagram: @pip-psp Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ParlInternship/ PIP Annual Report 2021 Director’s Message I am delighted to present the Parliamentary Internship Programme’s (PIP) 2020-21 Annual Report to the Canadian Political Science Association (CPSA). The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically reshaped the experience of the 2020-21 internship cohort relative to previous years. Such changes began with a mostly-virtual orientation in September, and continued with remote work in their MP placements, virtual study tours, and Brown-Bag lunches over Zoom. Yet while limiting some aspects of the PIP experience, the pandemic provided opportunities as well. The interns took full advantage of the virtual format to meet with academics, politicians, and other public figures who were inaccessible to previous cohorts relying on in-person meetings. They also learned new skills for online engagement that will serve them well in the hybrid work environment that is emerging as COVID-19 recedes. One thing the pandemic could not change was the steadfast support of the PIP’s various partners. We are greatly indebted to our sponsors who chose to prioritize their contributions to PIPs despite the many pressures they faced. In addition to their usual responsibilities for the Programme, both the PIP’s House of Commons Liasion, Scott Lemoine, and the Programme Assistant, Melissa Carrier, also worked tirelessly to ensure that the interns were kept up to date on the changing COVID guidance within the parliamentary preccinct, and to ensure that they had access to the resources they needed for remote work. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord ..........................................................................