Safeguards for Minorities Versus Sovereignty of Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hist. 450: the Making of Modern South Asia (3 Credits)

Hist. 450: The Making of Modern South Asia (3 Credits) (The agreement signed between Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and President J.R. Jayewardene, on the deployment of Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF) to Sri Lanka, 1987, which would finally lead to Gandhi’s assassination in 1991 by a suicide bomber from the LTTE) Instructor: Dr. Mou Banerjee (Draft Syllabus, subject to changes at instructor’s discretion) Email: [email protected] Class Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 9.30 – 10.45 AM, Humanities 1217. Office hours: Mosse Humanities Building, Room 4115: Thursday 12.30 -2.00 pm and by email appointment. Students are required to meet with me at least once by the end of the fourth week of the semester – please set up a meeting through email. Credit Hours: This 3-credit course meets as a group for 3 hours per week (according to UW- Madison's credit hour policy, each lecture counts as 1.5 hours). The course also carries the expectation that you will spend an average of at least 2 hours outside of class for every hour in the classroom. In other words, in addition to class time, plan to allot an average of at least 6 hours per week for reading, writing, preparing for discussions, and/or studying for quizzes and exams for this course. 1 Course Requirements: 1. This course is a historical introduction to the postcolonial history, political identity and political consciousness in the South Asian nation-states of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Myanmar. We shall study the evolution of modern South Asia and the intricate relationship between the neighboring sovereign states that emerged out of the partition of colonial India in 1947 and their interactions with their immediate postcolonial neighbors, through close readings of primary sources and relevant historiographical and theoretical literature. -

'Netaji's Life Was More Important Than the Legends and Myths' Page 1 of 4

The Telegraph Page 1 of 4 Issue Date: Sunday , July 10 , 2011 ‘Netaji’s life was more important than the legends and myths’ Miami-based economist turned film-maker Suman Ghosh — who has also made a documentary on Amartya Sen — was in conversation with Sugata Bose, Netaji’s grandnephew, about the historian’s His Majesty’s Opponent — Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle Against Empire on the morning of the launch of the Penguin book. Metro sat in on the Netaji adda. Excerpts… Suman Ghosh: You are a direct descendent of Subhas Chandra Bose and your father (Sisir Kumar Bose) was involved in the freedom struggle with him. Did you worry about objectivity in treating a subject that was so close to you? Sugata Bose: I made a conscious decision to write this book as a historian. Not as a Sugata Bose speaks with (right) family member. My father always used to tell me that Netaji believed that his country and Suman Ghosh at Netaji Bhavan. family were coterminous. So if I’m a member of the Bose family by an accident of birth so Picture by Bishwarup Dutta are all of the people of India. In some ways, if there is a problem of objectivity it would apply to most people and scholars of the subcontinent. But I felt I had acquired the necessary critical distance from my subject to embark on this project when I did. Ghosh: Netaji has always been shrouded in myths and mysteries. He has primarily been characterised as a revolutionary and a warrior. -

"1943: One Year, One Man and a World at War" on Subhas Chandra Bose and His Singapore Saga

"1943: One Year, One Man and a World at War" on Subhas Chandra Bose and his Singapore saga Proudest Day - Netaji taking the Salute, MZ Kiami to his left - Singapore, July 5 1943 Seventy-five years ago, on July 4-5, 1943, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose accepted the leadership of the Indian independence movement and the Supreme Command of the To sign up for this Indian National Army in Singapore. At the beginning of the year event, he was in Europe, waiting to find a way to travel to Asia. He did kindlyRegister so by a perilous 90-day submarine voyage between February online. and May 1943. After proclaiming the Azad Hind (Free India) Government in Singapore on October 21, 1943, he would stand DATE on Indian soil in the Andaman island by December 1943. This 25 August 2018 richly illustrated lecture will focus on the historical significance (Saturday) of the saga of one man during one year amidst a world at war. TIME 3.00pm to 4.30pm Guest-of-Honor: HE Mr Jawed Ashraf VENUE High Commissioner of India to the Republic of Singapore. Singapore Management University OPENING REMARK Function Room 6.1 3:00 pm 81 Victoria Street K Kesavapany Level 6 Governor, Singapore International Foundation Singapore 188065 INTRODUCTION Nilanjana Sengupta 3:15 pm Author of A Gentleman's Word: The Legacy of Subhas Chandra Bose in Southeast Asia PRESENTATION Sugata Bose 3:30 pm Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs at Harvard University 4:15 pm Q & A SESSION 4:30 pm NETWORKING & REFRESHMENTS Sugata Bose is the Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs at Harvard University. -

Tagore's Asian Voyages

THE NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, commemorates the 150th anniversary of World Poet Rabindranath Tagore Tagore’s Asian Voyages SELECTED SPEECHES AND WRITINGS ON RABINDRANATH TAGORE Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Logo in Full Color PROCESS COLOR : 30 Cyan l 90 Magenta l 90 Yellow l 20 Black PROCESS COLOR : 40 Cyan l 75 Magenta l 65 Yellow l 45 Black PROCESS COLOR : 50 Cyan l 100 Yellow PROCESS COLOR : 30 Cyan l 30 Magenta l 70 Yellow l 20 Black PROCESS COLOR : 70 Black PROCESS COLOR : 70 Cyan l 20 Yellow The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, pursues research on historical interactions among Asian societies and civilisations. It serves as a forum for comprehensive study of the ways in which Asian polities and societies have interacted over time through religious, cultural, and economic exchanges and diasporic networks. The Centre also offers innovative strategies for examining the manifestations of hybridity, convergence and mutual learning in a globalising Asia. http://nsc.iseas.edu.sg/ 1 CONTENTS 3 Preface Tansen Sen 4 Tagore’s Travel Itinerary in Southeast Asia 8 Tagore in China 10 Rabindranath Tagore and Asian Universalism Sugata Bose 19 Rabindranath Tagore’s Vision of India and China: A 21st Century Perspective Nirupama Rao 24 Realising Tagore’s Dream For Good Relations between India and China George Yeo 26 A Jilted City, Nobel Laureates and a Surge of Memories – All in One Tagorean Day Asad-ul Iqbal Latif 28 Tagore bust in Singapore – Unveiling Ceremony 30 Centenary Celebration Message Lee Kuan Yew 31 Messages 32 NSC Publications Compiled and designed by Rinkoo Bhowmik Editorial support: Joyce Iris Zaide 1 Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Projects Research Projects Lecture Series The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre hosts pursues a range of research projects three lecture series focusing on intra- Asian interactions: The Nalanda-Sriwijaya within the following areas: 6. -

Download Flyer

ANTHEM PRESS INFORMATION SHEET Azad Hind Subhas Chandra Bose, Writing and Speeches 1941-1943 Edited by Sisir K. Bose and Sugata Bose Pub Date: October 2004 Category: HISTORY / Asia / General Binding: Paperback BISAC code: HIS003000 Price: £14.95 / $32.95 BIC code: HBJF ISBN: 978184330839 Extent: 200 pages Rights Held: World Size: 234 x 156mm / 9.2 x 6.1 Description A collection of Subhas Chandra Bose’s writings and speeches, 1941–1943. This volume of Netaji Bose’s collected works covers perhaps the most difficult, daring and controversial phase in the life of India’s foremost anti-colonial revolutionary. His writings and broadcasts of this period cover a broad range of topics, including: the nature and course of World War Two; the need to distinguish between India’s internal and external policy in the context of the international war crisis; plans for a final armed assault against British rule in India; dismay at, and criticism of, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union; the hypocrisy of Anglo- American notions of freedom and democracy; the role of Japan in East and South East Asia; the reasons for rejecting the Cripps offer of 1942; support for Mahatma Gandhi and the Quit India movement later that year and reflections on the future problems of reconstruction in free India. Readership: For students and scholars of Indian history and politics. Contents List of Illustrations; Dr Sisir Kumar Boses and Netaji's Work; Acknowledgements; Introduction, Writings and Speeches; 1. A Post-Dated Letter; 2. Forward Bloc: Ist Justifications; 3. Plan of Indian Revolution; 4. Secret Memorandum to the German Governemtn; 5. -

Gandhi and Bose Are Highly Exaggerated and He Notes That Their Relationship Was Marked by Mutual Appreciation and a Sense of Admiration for Each Other

62 Gandhi and Bose Nikhil Katara Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Readings in the Shed [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 63 Abstract: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was a lawyer and freedom fighter who employed non-violent means to fight the British during the freedom struggle. Subhas Chandra Bose was an Indian Nationalist who used military means to attain India’s freedom from British rule. They are important freedom fighters that worked in India’s freedom struggle and they are often cited, quoted and referenced in the course of India’s struggle against colonialism. But due to their differences in approach to achieve the same, namely Gandhi’s non-violent means to fight for freedom, and Bose’s militaristic means, they are often considered as adversaries in all domains. The paper considers their relationship through correspondences between the said historical figures, speeches, conversations with their living family members and other historical information to evaluate if their ideologies had a meeting ground and whether their differences are exaggerated. The relationship between Gandhi & Bose is an important one for various reasons. The two are often quoted, and remembered for their support towards the cause of the Indian freedom struggle, though they are also accepted to be different from each other as far as ideological principles are concerned. Gandhi, with an Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume interest in fighting for freedom through non-violent means is often considered to be at odds with Subhas Chandra Bose, who was willing to adopt military means Sambhāṣaṇ Sambhāṣaṇ Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 64 to fight for India’s freedom struggle. -

Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal (Eds.), Nationalism, Democracy and Development: State and Politics in India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998-9

(Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal (eds.), Nationalism, Democracy and Development: State and Politics in India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998-9) Exploding Communalism: The Politics of Muslim Identity in South Asia Ayesha Jalal Farewell O Hindustan, O autumnless garden We your homeless guests have stayed too long Laden though we are today with complaints The marks of your past favors are upon us still You treated strangers like relations We were guests but you made us the hosts .... You gave us wealth, government and dominion For which of your many kindnesses should we express gratitude But such hospitality is ultimately unsustainable All that you gave you kept in the end Well, one has a right to one's own property Take it from whoever you want, give it to whoever you will Pull out our tongues the very instant They forgetfully utter a word of complaint about this But the complaint is that what we brought with us That too you took away and turned us into beggars .... You've turned lions into lowly beings, O Hind Those who were Afghan hunters came here to become the hunted ones We had foreseen all these misfortunes When we came here leaving our country and friends We were convinced that adversity would befall us in time And we O Hind would be devoured by you .... So long as O Hindustan we were not called Hindi We had some graces which were not found in others 2 .... You've made our condition frightening We were fire O Hind, you've turned us into ash.1 Altaf Husain Hali (1837-1914) in his inimitable way captures the dilemma of Muslim identity as perceived by segments of the ashraf classes in nineteenth century northern India. -

HIST 312 040: SOUTH ASIA and FILM SUMMER II 2014 MTW 6:00 – 9:0 P.M., F G78 Aryendra Chakravartty Department of History Liberal Arts North 355

HIST 312 040: SOUTH ASIA AND FILM SUMMER II 2014 MTW 6:00 – 9:0 P.M., F G78 Aryendra Chakravartty Department of History Liberal Arts North 355 Contact Information: E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (936) 468-2149 Office Hours: MTWR 10:45 – 12:00 pm or by appointment. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course surveys the history of Modern South Asia through the lens of Indian cinema ranging from popular Bollywood movies to more critically acclaimed regional films. Indian cinema often evokes images of colorful costumes, and a genre of story telling that is punctuated with enthralling songs and dances. Beyond all the glitter, Indian cinema lends itself as a useful tool to explore social, political, cultural and historical issues. This course is going to use South Asian films and scholarly articles and monographs to explore the complexities of colonial and postcolonial South Asia. BOOK: The following book is required for the course - Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal, Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy. Additional Readings: Assigned readings aside from these required texts will be available on the course website. POLICIES AND PROCEDURES Academic Integrity (A-9.1) Academic integrity is a responsibility of all university faculty and students. Faculty members promote academic integrity in multiple ways including instruction on the components of academic honesty, as well as abiding by university policy on penalties for cheating and plagiarism. Definition of Academic Dishonesty Academic dishonesty includes both cheating and plagiarism. Cheating includes but is not limited to (1) using or attempting to use unauthorized materials to aid in achieving a better grade on a component of a class; (2) the falsification or invention of any information, including citations, on an assigned exercise; and/or (3) helping or attempting to help another in an act of cheating or plagiarism. -

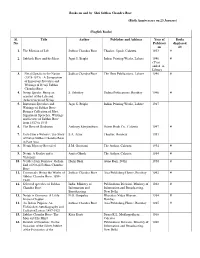

Books on and by Shri Subhas Chandra Bose

Books on and by Shri Subhas Chandra Bose (Birth Anniversary on 23 January) (English Books) Sl. Title Author Publisher and Address Year of Books No. Publicati displayed on (#) 1. The Mission of Life Subhas Chandra Bose Thacker, Spink, Calcutta 1933 # 2. Subhash Bose and his Ideas Jagat S. Bright Indian Printing Works, Lahore 1946 # (Year added in Library 3. Netaji Speaks to the Nation Subhas Chandra Bose The Hero Publications, Lahore 1946 # (1928-1945) : A Symposium of Important Speeches and Writings of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose 4. Netaji Speaks: Being an S. Subuhey Padma Publications, Bombay 1946 # account of the Life and Achievements of Netaji 5. Important Speeches and Jagat S. Bright Indian Printing Works, Lahore 1947 Writings of Subhas Bose: Being a Collection of Most Significant Speeches, Writings and Letters of Subhas Bose from 1927 to 1945 6. The Hero of Hindustan Anthony Elenjimittam Orient Book Co., Calcutta 1947 # 7. Unto Him a Witness; The Story S.A. Aiyar Thacker, Bombay 1951 of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in East Asia 8. Netaji Mystery Revealed S.M. Goswami The Author, Calcutta 1954 # 9. Netaji: A Realist and a Amita Ghosh The Author, Calcutta 1954 # Visionary 10. Verdict from Formosa: Gallant Harin Shah Atma Ram, Delhi 1956 # End of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose 11. Crossroads: Being the Works of Subhas Chandra Bose Asia Publishing House, Bombay 1962 # Subhas Chandra Bose, 1938- 1940 12. Selected speeches of Subhas India. Ministry of Publications Division, Ministry of 1962 # Chandra Bose Information and Information and Broadcasting, Broadcasting New Delhi 13. Netaji in Germany: A Little N.G. -

2019 Fall – Banerjee

History 142: South Asia, Past and Present (3 credits). Instructor: Dr. Mou Banerjee Email: [email protected] Class Hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 8:00-9:15am, Ingraham 224. Office hours: Mosse Humanities Building, Room 4115: Thursday 12.30 -2.00 pm and by email appointment. Students are required to meet with me at least once by the end of the third week of the semester. Credit Hours: This 3-credit course meets as a group for 3 hours per week (according to UW- Madison's credit hour policy, each lecture counts as 1.5 hours). The course also carries the expectation that you will spend an average of at least 2 hours outside of class for every hour in the classroom. In other words, in addition to class time, plan to allot an average of at least 6 hours per week for reading, writing, preparing for discussions, and/or studying for quizzes and exams for this course. Course Description: The South Asian Subcontinent, site of one of oldest civilizations of the world, and home to one- fourth of the world’s population, is a study in paradoxes. Culturally complex, religiously syncretic yet divisive, politically tumultuous, the subcontinent is a melting-pot of languages, ethnicities, heterogeneous political and social regimes, and widely disparate economic and ecological habitats. From being shaped by one of the greatest empires of the early-modern period - the Mughals; to being the most important imperial possession of Britain in the nineteenth century – the jewel in the crown; and ultimately providing a mosaic of postcolonial nations experimenting with democracy and authoritarianism in varied measures of success and tragedy, South Asia is both a world unto itself and a central node to wider global connections. -

Encounters with Fascism and National Socialism in Non-European Regions

Südasien-Chronik - South Asia Chronicle 2/2012, S. 350-374 © Südasien-Seminar der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin ISBN: 978-3-86004-286-1 Encounters with Fascism and National Socialism in non-European Regions MARIA FRAMKE [email protected] Sugata Bose, His Majesty’s Opponent. Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle Against Empire, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011, 388 pages, ISBN 9780674047549, Price 29,99€. Ulrike Freitag and Israel Gershoni, eds. 2011. Arab Encounters with Fascist Propaganda 1933-1945. Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 37 (3), pp. 310-450, ISSN 0340-613X, Price 20.45€. Israel Gershoni and Götz Nordbruch, Sympathie und Schrecken. Begeg- nungen mit Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus in Ägypten, 1922-1937. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 2011, 320 pages, ISBN 9783879977109, Price 32.00€. Mario Prayer, 2010. Creative India and the World. Bengali Interna- tionalism and Italy in the Interwar Period. In: S. Bose & K. Manjapra, 350 eds. Cosmopolitan Thought Zones. South Asia and the Global Circu- lation of Ideas. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 236-259, ISBN 9780230243378, Price 74.00€. Benjamin Zachariah, 2010. Rethinking (the Absence of) Fascism in In- dia, c. 1922-45. In: S. Bose & K. Manjapra, eds. Cosmopolitan Thought Zones. South Asia and the Global Circulation of Ideas. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 178-209, ISBN 9780230243378, Price 74.00€. 1. “In India there are no fascists”, claimed Jawaharlal Nehru1 in an inter- view with the correspondent of the Rudé Právo, the daily of the Com- munist Czech Party in July 1938. He went on explaining: REVIEW ESSAY/FORSCHUNGSBERICHT Among the hundreds of millions of Indians there is hardly a per- son who would sympathise with the parties of the totalitarian powers. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Captain Lakshmi Sahgal

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Captain Lakshmi Sahgal Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Captain Lakshmi Sahgal (1914-2012) Freedom fighter, social activist and the first woman commander of Indian National Army, Lakshmi Sahgal nee Swaminadhan was born on 24 October 1914 in Madras (now Chennai) to S. Swaminadhan, a criminal lawyer at Madras High Court, and Ammu Swaminadhan, a social worker and freedom fighter. Inspired by the progressive views of her mother, Lakshmi broke social convention and dogmas from a very early stage speaking out against the caste practices in Kerala. She joined the Queen Mary’s College, Madras in 1932. She was married at a young age to P.K.N Rao, a pilot. However, the marriage was not a success and she returned to her hometown to resume her studies. She completed her MBBS in 1938 from Madras Medical College. She also obtained a diploma in gynaecology and obstetrics from the same college in 1940 and joined the Government Kasturba Gandhi Hospital, Madras. Thereafter, she moved to Singapore and established a clinic for the poor and migrant workers from India. She also got closely associated with the India Independence League, founded in 1941 by Rash Behari Bose. In 1942, during the Japanese occupation of Singapore Dr. Lakshmi provided medical aid to the prisoners of war. Subhas Chandra Bose visited Singapore in July 1943 and took over the leadership of the League along with the Indian National Army. Dr. Lakshmi was inspired and fascinated by the charismatic leadership of Bose and expressed her desire to work with him.