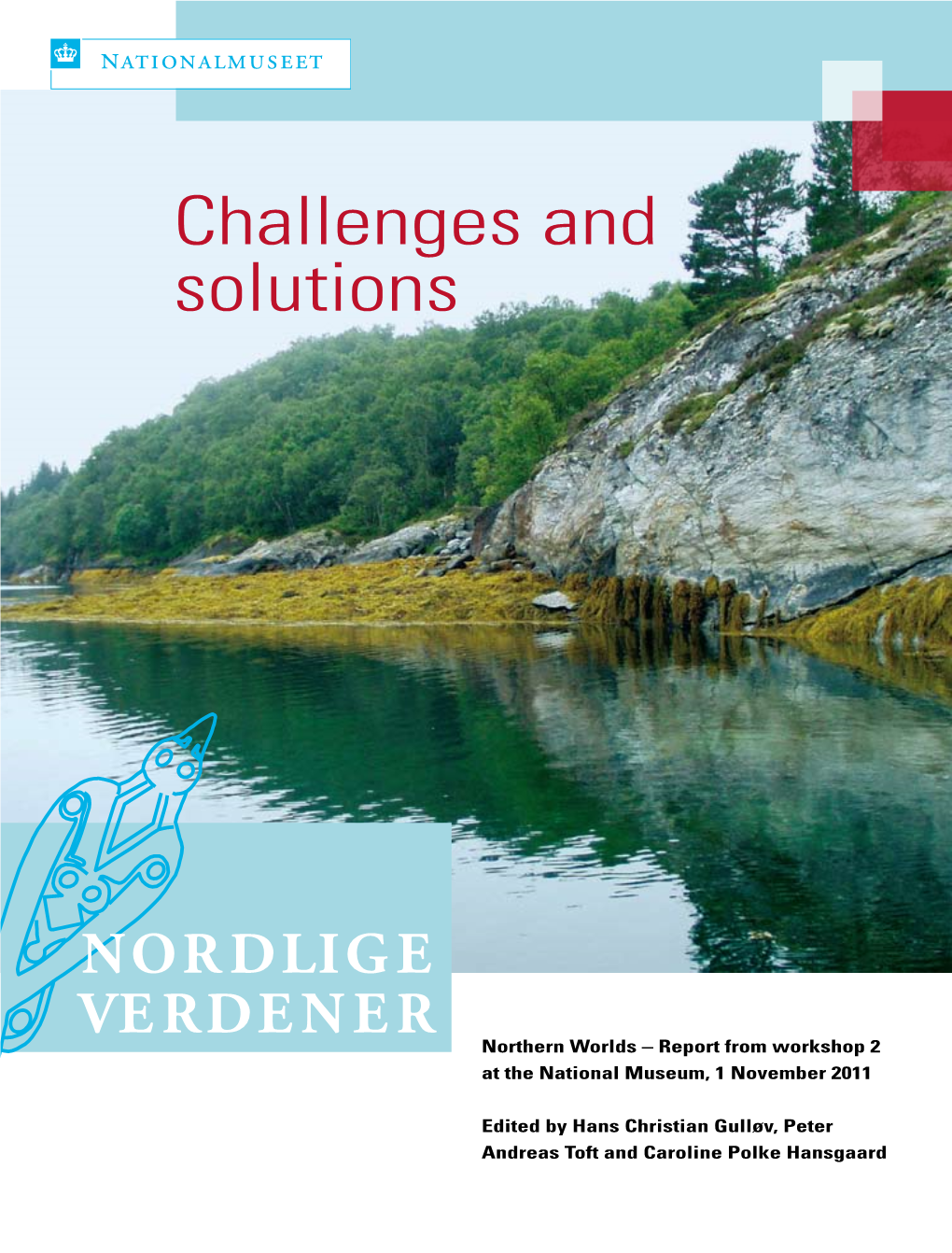

Challenges and Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Consequences of Sea-Ice Decline Eric Post Et Al

SPECIALSECTION 31. K. B. Ritchie, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 322,1–14 (2006). 52. C. Moritz, R. Agudo, Science 341, 504–508 (2013). 71. A. J. McMichael, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 32. B. Humair et al., ISME J. 3, 955–965 (2009). 53. C. D. Thomas et al., Nature 427, 145–148 4730–4737 (2012). 33. D. Corsaro, G. Greub, Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19,283–297 (2006). (2004). 72. T. Wheeler, J. von Braun, Science 341, 508–513 34. W. Jetz et al., PLoS Biol. 5, e157 (2007). 54. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Summary (2013). 35. B. J. Cardinale et al., Nature 486,59–67 (2012). for Policymakers. Climate Change 2007: The Physical 73. S. S. Myers, J. A. Patz, Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34, 36. P. T. J. Johnson, J. T. Hoverman, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth 223–252 (2009). 109,9006–9011 (2012). Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on 74. C. A. Deutsch et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 37. F. Keesing et al., Nature 468, 647–652 (2010). Climate Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, 2007). 6668–6672 (2008). 38. P. H. Hobbelen, M. D. Samuel, D. Foote, L. Tango, 55. S. Laaksonen et al., EcoHealth 7,7–13 (2010). D. A. LaPointe, Theor. Ecol. 6,31–44 (2013). 56. O. Gilg et al., Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1249, 166–190 (2012). Acknowledgments: This work was supported in part by an NSF 39. T. -

Marine and Terrestrial Investigations in the Norse Eastern Settlement, South Greenland

Marine and terrestrial investigations in the Norse Eastern Settlement, South Greenland Naja Mikkelsen,Antoon Kuijpers, Susanne Lassen and Jesper Vedel During the Middle Ages the Norse settlements in included acoustic investigations of possible targets Greenland were the most northerly outpost of European located in 1998 during shallow-water side-scan sonar Christianity and civilisation in the Northern Hemisphere. investigations off Igaliku, the site of the Norse episco- The climate was relatively stable and mild around A.D. pal church Gardar in Igaliku Fjord (Fig. 2). A brief inves- 985 when Eric the Red founded the Eastern Settlement tigation of soil profiles was conducted in Søndre Igaliku, in the fjords of South Greenland. The Norse lived in a once prosperous Norse settlement that is now partly Greenland for almost 500 years, but disappeared in the covered by sand dunes. 14th century. Letters in Iceland report on a Norse mar- riage in A.D. 1408 in Hvalsey church of the Eastern Settlement, but after this account all written sources remain silent. Although there have been numerous stud- Field observations and preliminary ies and much speculation, the fate of the Norse settle- results ments in Greenland remains an essentially unsolved question. Sandhavn Sandhavn is a sheltered bay that extends from the coast north-north-west for approximately 1.5 km (Fig. 2). The entrance faces south-east and it is exposed to waves Previous and ongoing investigations and swells from the storms sweeping in from the Atlantic The main objective of the field work in the summer of around Kap Farvel, the south point of Greenland. -

New Facts and Additional Information Supporting the Cop16

NOVEMBER 2012 NRDC ISSUE PAPER IP:12-11-A New Facts and Additional Information Supporting the CoP16 Polar Bear Proposal Submitted by the United States of America About NRDC NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) is a national nonprofit environmental organization with more than 1.3 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Montana, and Beijing. Visit us at www.nrdc.org. NRDC’s policy publications aim to inform and influence solutions to the world’s most pressing environmental and public health issues. For additional policy content, visit our online policy portal at www.nrdc.org/policy. NRDC Director of Communications: Phil Gutis NRDC Deputy Director of Communications: Lisa Goffredi NRDC Policy Publications Director: Alex Kennaugh Lead Editor: Design and Production: www.suerossi.com Cover photo © Paul Shoul: paulshoulphotography.com © Natural Resources Defense Council 2012 n October 4, 2012, the United States, supported by the Russian Federation, submitted a proposal to transfer the polar bear, Ursus maritimus, from OAppendix II to Appendix I of the Convention in accordance with Article II and Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP15) on the basis that the polar bear is affected by trade and shows a marked decline in the population size in the wild, which has been inferred or projected on the basis of a decrease in area of habitat and a decrease in quality of habitat. Pursuant to the Convention, “Appendix I shall include all species threatened with extinction which are or may be affected by trade.” CITES Article II, paragraph 1. -

Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends Over Pan-Arctic Tundra

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4229-4254; doi:10.3390/rs5094229 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra Uma S. Bhatt 1,*, Donald A. Walker 2, Martha K. Raynolds 2, Peter A. Bieniek 1,3, Howard E. Epstein 4, Josefino C. Comiso 5, Jorge E. Pinzon 6, Compton J. Tucker 6 and Igor V. Polyakov 3 1 Geophysical Institute, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, P.O. Box 757000, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.W.); [email protected] (M.K.R.) 3 International Arctic Research Center, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, 930 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, 291 McCormick Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Cryospheric Sciences Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Biospheric Science Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.E.P.); [email protected] (C.J.T.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-474-2662; Fax: +1-907-474-2473. -

Og Miljøudvalget

Teknik- og Miljøudvalget Referat 6. december 2016 kl. 16:00 Udvalgsværelse 1 Indkaldelse Bodil Kornbek Mette Schmidt Olsen Henriette Breum Jakob Engel-Schmidt Henrik Brade Johansen Birgitte Hannibal Aase Steffensen Jakob Engel-Schmidt var fraværende i stedet deltog Søren P Rasmussen. Derudover deltog: Bjarne Holm Markussen Sidsel Poulsen Christian Røn Østeraas Mads Henrik Lindberg Chritiansen Thomas Hansen Katrine Lindegaard (referent) Indholdsfortegnelse Pkt. Tekst Side 1 3. anslået regnskab 2016 - Teknik- og Miljøudvalgets område (Beslutning) 3 2 Proces for udmøntning af budgetaftalen for 2017-2020 (Beslutning) 5 3 Brune turistoplysningstavler langs motorveje i kommunen (Beslutning) 7 4 Valg af skrifttype til vejnavneskilte (Beslutning) 11 5 Lyngby-Taarbæk Kommunes deltagelse i Loop City-samarbejdet (Beslutning) 15 6 Igangværende mobilitetsprojekter (Orientering) 17 7 Etablering af affaldsskakte ved nybyggeri (Beslutning) 19 8 Takster for vand og spildevand 2017 (Beslutning) 21 Trafikale skitseprojekter i forbindelse med byudvikling langs Helsingørmotorvejen 9 25 (Beslutning) Deltagelse i Vejdirektoratets udbud i 2017 af daglig vedligeholdelse af Lyngby 10 30 Omfartsvej (Beslutning) 11 Kommende sager 32 12 Lukket punkt, Miljøsag 33 13 Meddelelser 34 2 Punkt 1 3. anslået regnskab 2016 - Teknik- og Miljøudvalgets område (Beslutning) Resumé Teknik- og Miljøudvalget skal behandle forvaltningens redegørelse vedrørende 3. anslået regnskab for 2016 og indstille til Økonomiudvalget og Kommunalbestyrelsen. Forvaltningen foreslår, at udvalget: 1. drøfter redegørelsen om 3. anslået regnskab på udvalgets område 2. tager redegørelsen til efterretning. Sagsfremstilling 3. anslået regnskab er udarbejdet på baggrund af korrigeret budget 2016, forbruget pr. 30. september 2016 og skøn for resten af året. Økonomiudvalget drøftede 3. anslået regnskab d. 17. november 2016 og besluttede, at tage redegørelsen til efterretning og at oversende redegørelsen til fagudvalgene. -

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife CAFF CBMP Report No. 20 discover the arctic species trend index: www.asti.is ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • The Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, the Environmental Agency, the Government of Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organisations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) Greenland, Alaska and Canada • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • The Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen. 2010. Arctic Species Trend Index 2010: Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife. CAFF CBMP Report No. 20, CAFF International Secretariat, Akureyri, Iceland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Website: www.caff.is Design & Layout: Lily Gontard Cover photo courtesy of Joelle Taillon. March 2010 ___ CAFF Designated Area Report Authors: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen This report was commissioned by the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP) with funding provided by the Government of Canada. -

A Spatial Evaluation of Arctic Sea Ice and Regional Limitations in CMIP6 Historical Simulations

1AUGUST 2021 W A T T S E T A L . 6399 A Spatial Evaluation of Arctic Sea Ice and Regional Limitations in CMIP6 Historical Simulations a a a a MATTHEW WATTS, WIESLAW MASLOWSKI, YOUNJOO J. LEE, JACLYN CLEMENT KINNEY, AND b ROBERT OSINSKI a Department of Oceanography, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California b Institute of Oceanology of Polish Academy of Sciences, Sopot, Poland (Manuscript received 29 June 2020, in final form 28 April 2021) ABSTRACT: The Arctic sea ice response to a warming climate is assessed in a subset of models participating in phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), using several metrics in comparison with satellite observations and results from the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System and the Regional Arctic System Model. Our study examines the historical representation of sea ice extent, volume, and thickness using spatial analysis metrics, such as the integrated ice edge error, Brier score, and spatial probability score. We find that the CMIP6 multimodel mean captures the mean annual cycle and 1979–2014 sea ice trends remarkably well. However, individual models experience a wide range of uncertainty in the spatial distribution of sea ice when compared against satellite measurements and reanalysis data. Our metrics expose common and individual regional model biases, which sea ice temporal analyses alone do not capture. We identify large ice edge and ice thickness errors in Arctic subregions, implying possible model specific limitations in or lack of representation of some key physical processes. We postulate that many of them could be related to the oceanic forcing, especially in the marginal and shelf seas, where seasonal sea ice changes are not adequately simulated. -

Thinking About the Arctic's Future

By Lawson W. Brigham ThinkingThinking aboutabout thethe Arctic’sArctic’s Future:Future: ScenariosScenarios forfor 20402040 MIKE DUNN / NOAA CLIMATE PROGRAM OFFICE, NABOS 2006 EXPEDITION The warming of the Arctic could These changes have profound con- ing in each of the four scenarios. mean more circumpolar sequences for the indigenous people, • Transportation systems, espe- for all Arctic species and ecosystems, cially increases in marine and air transportation and access for and for any anticipated economic access. the rest of the world—but also development. The Arctic is also un- • Resource development—for ex- an increased likelihood of derstood to be a large storehouse of ample, oil and gas, minerals, fish- yet-untapped natural resources, a eries, freshwater, and forestry. overexploited natural situation that is changing rapidly as • Indigenous Arctic peoples— resources and surges of exploration and development accel- their economic status and the im- environmental refugees. erate in places like the Russian pacts of change on their well-being. Arctic. • Regional environmental degra- The combination of these two ma- dation and environmental protection The Arctic is undergoing an jor forces—intense climate change schemes. extraordinary transformation early and increasing natural-resource de- • The Arctic Council and other co- in the twenty-first century—a trans- velopment—can transform this once- operative arrangements of the Arctic formation that will have global im- remote area into a new region of im- states and those of the regional and pacts. Temperatures in the Arctic are portance to the global economy. To local governments. rising at unprecedented rates and evaluate the potential impacts of • Overall geopolitical issues fac- are likely to continue increasing such rapid changes, we turn to the ing the region, such as the Law of throughout the century. -

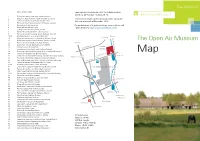

Natmus M65 Folder ENG.Indd.Ps, Page 2 @ Preflight

Free admission MUSEUM BUILDINGS Opening hours: From Easter until the Autumn holiday (week no. 42) Tuesday – Sunday 10-17. 1 Fisherman’s cottage from Agger, North Sea Coast 2 Skipper’s cottage from the island Fanø, North Sea Coast The museum is open for Christmas activities during the 3 Farmstead from the island Bornholm. Water mill first two weekends of December 10-16. 4 Farmstead from Ostenfeld, Southern Schleswig, Germany 5 Fuglevad wind mill, original site For guided tours in English and larger events, please call 6 Water mill from Ellested, Funen +45 33 47 38 57 or mail [email protected] 7 Gaming stone from Løve, Central Jutland 8 Farmstead from Karup Hearth, Central Jutland 9 Farmstead from the island Læsø in the Kattegat. Post mill 15-19 Buildings from the Faeroe islands. Water mill Nærum Helsingør 20 Milestone from the district of Holstebro, Western Jutland 21 Bridge from Smedevad near Holstebro, Western Jutland The Open Air Museum 22 Farmstead from Vemb, Western Justland. Forge Hillerød 25 Manor from Fjellerup, Djursland, Eastern Jutland 26 Summerhouse from Stege, Møn Brede Skodsborgvej 27 Summerhouse from Skovshoved, Northern Zealand Works 29 Fisherman’s huts from Nymindegab, Western Jutland. Dismantled Map 30 Farmstead from Lønnestak, Western Jutland 31 Farmstead from Eiderstedt (Hauberg), Southern Schleswig, Germany Brede St. Kongevejen 201 I.C. Modewegs s 32 Farmstead from Southern Sejerslev, Northern Schleswig Vej 33 Lace-making school from Northern Sejerlev, Northern Schleswig Bredevej 34 Farmstead from the island Rømø, North Sea Coast P 37-40 Buildings from the North-Eastern Schleswig 41 Shoemaker’s cottage from Ødis Bramrup, Eastern Jutland The Open Air Museum 42 Farmstead from True near Århus, Eastern Jutland 43 Potter’s workshop from Sorring, Eastern Jutland 44-45 Smallholder’s farmstead and barn from Als, Northern Schleswig 54 Farmstead from Halland, Sweden 55 Twin farmstead form Göinge, Scania, Sweden P Fuglevad St. -

Some Aspects of the Thermal Energy Exchange on the South Polar Snow Field and Arctic Ice Pack'

MAY 1961 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 173 SOME ASPECTS OF THE THERMAL ENERGY EXCHANGE ON THE SOUTH POLAR SNOW FIELD AND ARCTIC ICE PACK' KIRBY J. HANSON Po!ar Meteorology Research Project, US. Weather Bureau, Washington, D.C. [Manuscript received September 13, 1960; revised February 21, 1961 ] ABSTRACT Solar and terrestrial radiation measurements that were obtained at Amundsen-Scot>t (South Pole) Station and on Ice lsland (Bravo) T-3 are presented for representative summer and winter months. Of the South Polar net radiation loss during April 1958, approximately20 percent of the energy came from the snow and80 percent from the air. The actual atmospheric cooling rate during that period was only about lj6 of the suggested radiative cooling rate. The annual net radiation at various places in Antarctica is presented. During 1058, the South Polar atmos- phere transmitted about 73 percent of the annual extraterrestrial radiation, while at T-3 the Arctic atmosphere transmitted about 56 percent. The albedo of melting sea ice is discussed. Measurements on T-3 during July 1958 indicate that the net radiation is positive on both clear and overcast days but greatest on overcast days. Refreezing of the surface with clear skies, as observed by Untersteiner and Badglep, is discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION Ocean.ThisIsland wasabout by 5 11 miles in size and The elliptical orbit of the earthbrings it about 3 million about 52 meters thick (Crary et al. [2]) in 1953 when it miles farther from the sun at aphelion than at perihelion; drifted near 88' N., looo W. In the years that followed, consequently,during midsummer, about 7 percent less this it drifted southward and in July 1958 was located solar radiation impinges on the top of the Arctic atrnos- 79.5' N., 118' W. -

Address by the President of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference

Address by the President of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference Rosemarie Kuptana President, Inuit Circumpolar Conference, Ontario, Canada Keywords: Inuit Circumpolar Conference; Inuit; Self-determination-, Health issues; Research relationships I am very pleased to be here to speak to The connection between indigenous self you about circumpolar health from an Inuit per determination issues and circumpolar health spective. The agenda for this tenth meeting of may not seem clear at fist. It may help if one the International Congress on Circumpolar recognizes that self-determination and sover Health covers a wide range of health issues vi eignty issues are fundamentally about power, tally important to circumpolar peoples, such as and about how power is exercised and who ex benefits and risks of subsistence foods, cancer ercises it over self, family, community, and na prevention, diabetes, alcohol abuse, traditional tion. I will try to explain from an Inuit perspec knowledge and healing, and environmental tive how certain power relationships have real health, to name a few. life impacts on the day-to-day lives of Inuit as As you know, Inuit are a circumpolar we seek to maintain and develop the health of people, whose territories span the northern our families and communities. I will speak to reaches of four nations: the United States power relationships between peoples and be (Alaska), Canada, Greenland, and Russia. The tween individuals, and I hope that my comments Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) is the in will have some resonance in your discussions ternational organization of the approximately of the many important circumpolar health is 130,000 Inuit who live in these four circumpo sues on your agenda. -

Downloaded 10/01/21 10:31 PM UTC 874 JOURNAL of CLIMATE VOLUME 12

MARCH 1999 VAVRUS 873 The Response of the Coupled Arctic Sea Ice±Atmosphere System to Orbital Forcing and Ice Motion at 6 kyr and 115 kyr BP STEPHEN J. VAVRUS Center for Climatic Research, Institute for Environmental Studies, University of WisconsinÐMadison, Madison, Wisconsin (Manuscript received 2 February 1998, in ®nal form 11 May 1998) ABSTRACT A coupled atmosphere±mixed layer ocean GCM (GENESIS2) is forced with altered orbital boundary conditions for paleoclimates warmer than modern (6 kyr BP) and colder than modern (115 kyr BP) in the high-latitude Northern Hemisphere. A pair of experiments is run for each paleoclimate, one with sea-ice dynamics and one without, to determine the climatic effect of ice motion and to estimate the climatic changes at these times. At 6 kyr BP the central Arctic ice pack thins by about 0.5 m and the atmosphere warms by 0.7 K in the experiment with dynamic ice. At 115 kyr BP the central Arctic sea ice in the dynamical version thickens by 2±3 m, accompanied bya2Kcooling. The magnitude of these mean-annual simulated changes is smaller than that implied by paleoenvironmental evidence, suggesting that changes in other earth system components are needed to produce realistic simulations. Contrary to previous simulations without atmospheric feedbacks, the sign of the dynamic sea-ice feedback is complicated and depends on the region, the climatic variable, and the sign of the forcing perturbation. Within the central Arctic, sea-ice motion signi®cantly reduces the amount of ice thickening at 115 kyr BP and thinning at 6 kyr BP, thus serving as a strong negative feedback in both pairs of simulations.