Abraham Lincoln's Speeches and Letters, 1832-1865

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

University of Maryland Commencement May 22, 2020

University of Maryland Commencemenmay 22, 2020 Table of Contents CONGRATULATIONS BACHELOR’S DEGREES From the President 1 Agriculture and Natural Resources, From the Alumni Association President 2 College of 24 Architecture, Planning and SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Preservation, School of 25 Graduating Student Speaker 4 Arts and Humanities, College of 25 University Medalists 5 Behavioral and Social Sciences, Honorary Degree Recipients 7 College of 29 Commencement Speaker 9 Business, Robert H. Smith School of 35 Computer, Mathematical, and DOCTORAL DEGREES 10 Natural Sciences, College of 42 Education, College of 48 MASTER’S DEGREES 15 Engineering, A. James Clark School of 49 Graduate Certificates 22 Information Studies, College of 52 Journalism, Philip Merrill College of 53 Public Health, School of 54 Public Policy, School of 56 THE “DO GOOD” CAMPUS Undergraduate Studies 56 Certificate Programs 56 The University of Maryland commits to becoming HONORS COLLEGE, CITATION AND a global leader in advancing social innovation, NOTATION PROGRAMS, AND ACADEMIC AND SPECIAL AWARDS philanthropy and nonprofit leadership with its Do Honors College 57 Good Campus. CIVICUS 59 College Park Scholars 59 Beyond the Classroom 62 Our Do Good Campus effort amplifies the power of Federal Fellows 62 Terps as agents of social innovation and supports First-Year Innovation and Research Experience 62 the university’s mission of service. We’re working to Global Communities 63 ensure all University of Maryland students graduate Global Fellows 63 equipped and motivated to do good in their careers, Hinman CEOs 63 Immigration and Migration Studies 63 their communities and the world. Jiménez-Porter Writers’ House 63 Language House 63 Ronald E. -

Compiled by D. A. Sharpe Abraham Lincoln Was Born February 12

Compiled by D. A. Sharpe Abraham Lincoln was born February 12, 1809 on Sinking Spring Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky. He lived till assassinated by actor John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer on April 14, 1865 at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. He died April 15, the following day, at the Petersen House, Washington, D.C Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States. He is my 33rd cousin, twice removed. Our ancestors in common are Eystein Glumra Ivarsson and Aseda Rognvaldsdatter. They are ninth century Vikings of Norway who are Lincoln's 30th great grandparents and my 32nd great grandparents. Viewed another way, Abraham Lincoln is the 8th cousin, six times removed of the husband of the stepdaughter of my 6th great grand uncle, Danette Abney. President Lincoln is the thirteenth cousin, six times removed to President George Washington. Lincoln is the 19th cousin, six times removed to my son-in-law, Steven O. Westmoreland. Lincoln is a 33rd cousin, once removed, to Steve's wife (our daughter), Tiffany Lenn Sharpe Westmoreland. Tiffany and Steven are 34th cousins, four times removed to each other. I’m presuming that is not too close of family relation to be a marriage problem! 1 According to some sources, Lincoln's first romantic interest was Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he first moved to New Salem; these sources indicate that by 1835, they were in a relationship but not formally engage. She died at the age of 22 on August 25, 1835, most likely of typhoid fever. In the early 1830s, he met Mary Owens from Kentucky when she was visiting her sister. -

H. Doc. 108-222

THIRTIETH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1847, TO MARCH 3, 1849 FIRST SESSION—December 6, 1847, to August 14, 1848 SECOND SESSION—December 4, 1848, to March 3, 1849 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE M. DALLAS, of Pennsylvania PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—DAVID R. ATCHISON, 1 of Missouri SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKINS, 2 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—ROBERT BEALE, of Virginia SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—ROBERT C. WINTHROP, 3 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN B. FRENCH, of New Hampshire; THOMAS J. CAMPBELL, 4 of Tennessee SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—NEWTON LANE, of Kentucky; NATHAN SARGENT, 5 of Vermont DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT E. HORNER, of New Jersey ALABAMA CONNECTICUT GEORGIA SENATORS SENATORS SENATORS 14 Arthur P. Bagby, 6 Tuscaloosa Jabez W. Huntington, Norwich Walter T. Colquitt, 18 Columbus Roger S. Baldwin, 15 New Haven 19 William R. King, 7 Selma Herschel V. Johnson, Milledgeville John M. Niles, Hartford Dixon H. Lewis, 8 Lowndesboro John Macpherson Berrien, 20 Savannah REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Fitzgerald, 9 Wetumpka REPRESENTATIVES James Dixon, Hartford Thomas Butler King, Frederica REPRESENTATIVES Samuel D. Hubbard, Middletown John Gayle, Mobile John A. Rockwell, Norwich Alfred Iverson, Columbus Henry W. Hilliard, Montgomery Truman Smith, Litchfield John W. Jones, Griffin Sampson W. Harris, Wetumpka Hugh A. Haralson, Lagrange Samuel W. Inge, Livingston DELAWARE John H. Lumpkin, Rome George S. Houston, Athens SENATORS Howell Cobb, Athens Williamson R. W. Cobb, Bellefonte John M. Clayton, 16 New Castle Alexander H. Stephens, Crawfordville Franklin W. Bowdon, Talladega John Wales, 17 Wilmington Robert Toombs, Washington Presley Spruance, Smyrna ILLINOIS ARKANSAS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE John W. -

The Life of Abraham Lincoln

Mr. Lincoln: The Life of Abraham Lincoln Professor Allen C. Guelzo THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Allen C. Guelzo, Ph.D. Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of Civil War Era Studies, Gettysburg College Dr. Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of Civil War Era Studies at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He is also the Associate Director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. He was born in Yokohama, Japan, but grew up in Philadelphia. He holds an M.A. and Ph.D. in history from the University of Pennsylvania, where he wrote his dissertation under the direction of Bruce Kuklick, Alan C. Kors, and Richard S. Dunn. Dr. Guelzo has taught at Drexel University and, for 13 years, at Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania. At Eastern, he was the Grace Ferguson Kea Professor of American History, and from 1998 to 2004, he was the founding dean of the Templeton Honors College at Eastern. Dr. Guelzo is the author of numerous books on American intellectual history and on Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War era, beginning with his first work, Edwards on the Will: A Century of American Theological Debate, 1750– 1850 (Wesleyan University Press, 1989). His second book, For the Union of Evangelical Christendom: The Irony of the Reformed Episcopalians, 1873–1930 (Penn State University Press, 1994), won the Outler Prize for Ecumenical Church History of the American Society of Church History. He wrote The Crisis of the American Republic: A History of the Civil War and Reconstruction for the St. -

No. 14~ THEY ONLY INCREASE the STATURE of the MAN

Prepared in the Interests of Book Collecting at the The University of Michigan No. 14~ THEY ONLY INCREASE THE STATURE OF THE MAN. 1Sept 1947 A Little Dinner reminded us that we had more than two hours to for Lincoln wai t before the Lincoln At 12:01 A.M. on July Papers could be opened. 2G, 1947, the Robert Todd He proposed that we Lincoln Collection of pa might pass the time plea pers relating to his father, santly listening to some of Abraham Lincoln, was our company tell us what opened to the public. they hoped to find in the This was that moment for collection. ,..rh ich many men had Dr Evans called first on wai ted years. The faces of Carl Sandburg. With a those men grouped around gentle smile on his face, the safes which had held and in the Middle West the papers were bright ern voice familiar to all with hope or troubled Lincolnians, Mr Sandburg wi th fears and worries or announced that he would stilled to conceal emo accompany himself on his lions. Yet were they all ex guitar with songs of the pectanL This was the mo American past. First, there ment; starring 00'\'''' they was a Revolutionary War would have - or they song by Joseph Warren would not have-s-answers about his hopes for the 10 questions about Lin future of our America coln which puzzled them. and then there was a bal These Lincoln Papers Reprinted with permission of S. J. Ray and . lad of Lincoln's time- the Kansas City Star had been sealed at the in- about a boy and a girl. -

Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Central Skagit Rural Partial County Library District Regular Board Meeting Agenda April 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Via Zoom Meeting Platform 1. Call to Order 2. Public Comment 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Consent Agenda Items Approval of March 18, 2021 Regular Meeting Minutes Approval of March 2021 Payroll in the amount of $38,975.80 Approval of March 2021 Vouchers in the amount of $76,398.04 Treasury Reports for March 2021 Balance Sheet for March 2021 (if available) Deletion List – 5116 Items 5. Conflict of Interest 5. Communications 6. Director’s Report 7. Unfinished Business A. Library Opening Update B. Art Policy (N or D) 8. New Business A. Meeting Room Policy (N) B. Election of Officers 9. Other Business 10. Adjournment There may be an Executive Session at any time during the meeting or following the regular meeting. DocuSign Envelope ID: 533650C8-034C-420C-9465-10DDB23A06F3 Legend: E = Explore Topic N = Narrow Options D = Decision Information = Informational items and updates on projects Parking Lot = Items tabled for a later discussion Current Parking Lot Items: 1. Grand Opening Trustee Lead 2. New Library Public Use Room Naming Jeanne Williams is inviting you to a scheduled Zoom meeting. Topic: Board Meeting Time: Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Pacific Time (US and Canada) Every month on the Third Thu, until Jan 20, 2022, 11 occurrence(s) Mar 18, 2021 07:00 PM Apr 15, 2021 07:00 PM May 20, 2021 07:00 PM Jun 17, 2021 07:00 PM Jul 15, 2021 07:00 PM Aug 19, 2021 07:00 PM Sep 16, 2021 07:00 PM Oct 21, 2021 07:00 PM Nov 18, 2021 07:00 PM Dec 16, 2021 07:00 PM Jan 20, 2022 07:00 PM Please download and import the following iCalendar (.ics) files to your calendar system. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Liicoli Ooliection

F The Oliver R. Barrett LIICOLI OOLIECTION "Public Auction ^ale FEBRUARY 1 9 AND 20 at 1:45 and 8 p. m. at the Parke-Bernet Galleries- Inc • • 980 MADISON AVENUE ^J\Qw Yovk 1952 LINCOLN ROOM UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY MEMORIAL the Class of 1901 founded by HARLAN HOYT HORNER and HENRIETTA CALHOUN HORNER H A/Idly-^ nv/n* I Sale Number 1315 FREE PUBLIC EXHIBITION From Tuesday, February 12, to Date of Sale From 10 a. Tfj. to 5 p. m. y Tuesday 10 to 8 Closed Sunday and Monday PUBLIC AUCTION SALE Tuesday and Wednesday Afternoons and Evenings February 19 and 20, at 1 :45 and 8 p. m. EXHIBITION & SALE AT THE PARKE-BERNET GALLERIES • INC 980 Madison Avenue • 76th-77th Street New York 21 TRAFALGAR 9-8300 Sales Conducted by • • H. H. PARKE L. J. MARION A. N. BADE A. NISBET • W. A. SMYTH • C. RETZ 1952 THE LATE OLIVER R. BARRETT The Immortal AUTOGRAPH LETTERS ' DOCUMENTS MANUSCRIPTS ' PORTRAITS PERSONAL RELICS AND OTHER LINGOLNIANA Collected by the Late OLIVER R. BARRETT CHICAGO Sold by Order of The Executors of His Estate and of Roger W . Barrett i Chicago Public Auction Sale Tuesday and Wednesday February 19 and 20 at 1:45 and 8 p. m. PARKE-BERNET GALLERIES • INC New York • 1952 The Parke -Bernet Galleries Will Execute Your Bids Without Charge If You Are Unable to Attend the Sale in Person Items in this catalogue subject to the twenty per cent Federal Excise Tax are designated by an asterisk (*). Where all the items in a specific category are subject to the twenty per cent Federal Ex- cise Tax, a note to this effect ap- pears below the category heading. -

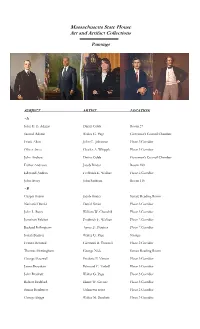

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

IILY ALBUM Robert Tcxld Loncoln Beckwith ( 1904-1985)

(')f/Hf/11 ~'/ / .'J.f/J teenth Pre'ldent. In 1965 he v.:h introduced to T HE L INCOLN FA\'IILY ALBUM Robert Tcxld Loncoln Beckwith ( 1904-1985). By Mark£. Neely. JJ: & Harold 1/ol:er the grcat-gran<hon of Prc,idcnt Lincoln. Thi' New York: Douhlec/ay.{/990{ meeting rc>ultcd in the eventual di,covery of m:U1) hotherto unknown Lincoln trea>ure,, not the lea.\! of Quarro. clorlr /mu/ing.xil'./72. {3/ (l<tges. S35.00 \\hich are the collectton of albums and photographs prc A Re1·inr by Ralph Geoffrey Neawuw SCI"ed for posterit) by four generation; of the Lincolns. We arc all indebted to the Lincoln National Life fn,ur Writing to llarvey G. E.1Stman. a Poughkeepsie. New :o~k :tncc Company for it' devotion to American hi-tory. particu abolitionist. who had requested a photograph of the llhnoas larly the Abraham Lincoln 'tory, and for acquiring thb lawyer-politician. Abmham Lincoln replied " I h:avc not a superb collection and placmg it m The Loncoln MlL\e~m on ,angle one nov. :u m) control: but I thin~ you can ~a,il) get Fort \\'a)ne. Indiana v.hcre It v.ill be a\atlable forth" and one at New-Yorl.. While I ""' there I "a' taken to one of future generations. In the many }Cal'\ \!nee th founding. the place-' "here they get up 'uch tlnng,, and I >uppo-e they Lincoln Life has given more than mere "hp o;ervice" to 1t' got my shaddow. and can multiply copie' indelinitely." use of the Lincoln name. -

Attributing the Bixby Letter: a Case of Historical Disputed Authorship

Attributing the Bixby Letter: A case of historical disputed authorship The Centre for Forensic Linguistics Authorship Group: Jack Grieve, Emily Carmody, Isobelle Clarke, Mária Csemezová, Hannah Gideon, Cristina Greco, Annina Heini, Andrea Nini, Maria Tagtalidou and Emily Waibel LSS Seminar Series Aston University, 13 April, 2016 Centre for Forensic Linguistic Authorship Group Staff and Students at the Centre for Forensic Linguistics have been conducting analyses of famous cases of disputed authorship for the past few years: CFLAG 2014: Jack Grieve and UG LE3031 Students: The Bitcoin White Paper CFLAG 2015: Andrea Nini and CFL MA students & staff: The Sony Hacker Case CFLAG 2016: Jack Grieve, CFL MA/PhD students & staff: The Bixby Letter The Bixby Letter In November 1864, in the midst of the Civil War and only 5 months before he would be assassinated, Abraham Lincoln sent a short letter of condolence to Lydia Bixby of Boston, who was believed to have lost five sons fighting for the Union. The Bixby Letter In fact, the Widow Bixby had only lost two sons and was also likely a brothel owner and a Confederate sympathiser, who had destroyed the letter in anger. Fortunately, the Adjutant General of Massachusetts, William Shouler, who had requested the letter from Lincoln, sent a copy to the Boston Evening Transcript. The Bixby Letter The Bixby Letter is considered to be one of the greatest pieces of correspondence in the history of the United States and one of Lincoln’s most celebrated texts, only surpassed by the Gettysburg Address and the Emancipation Proclamation. It has also become part of public culture, for example being featured in the movie Saving Private Ryan and being recited by President George W.