Copper, Borders and Nation-Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

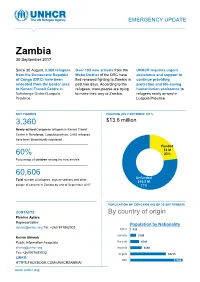

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

Files, Country File Africa-Congo, Box 86, ‘An Analytical Chronology of the Congo Crisis’ Report by Department of State, 27 January 1961, 4

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/113873/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Marsh, Stephen and Culley, Tierney 2018. Anglo-American relations and crisis in The Congo. Contemporary British History 32 (3) , pp. 359-384. 10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 file Publishers page: http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 <http://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY https://doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1477598 ARTICLE Congo, Anglo-American relations and the narrative of � decline: drumming to a diferent beat Steve Marsh and Tia Culley AQ2 AQ1 Cardiff University, UK� 5 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The 1960 Belgian Congo crisis is generally seen as demonstrating Congo; Anglo-American; special relationship; Anglo-American friction and British policy weakness. Macmillan’s � decision to ‘stand aside’ during UN ‘Operation Grandslam’, espe- Kennedy; Macmillan cially, is cited as a policy failure with long-term corrosive efects on 10 Anglo-American relations. -

Linguistics for the Use of African History and the Comparative Study of Bantu Pottery Vocabulary

LINGUISTICS FOR THE USE OF AFRICAN HISTORY AND THE COMPARATIVE STUDY OF BANTU POTTERY VOCABULARY Koen Bostoen Université Libre de Bruxelles1 Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren 1. Introduction Ever since African historical linguistics emerged in the 19th century, it has served a double purpose. It has not only been practiced with the aim of studying language evolution, its methods have also been put to use for the reconstruction of human history. The promotion of linguistics to one of the key disciplines of African historiography is an inevitable consequence of the lack of ancient written records in sub-Saharan Africa. Scholars of the African past generally fall back on two kinds of linguistic research: linguistic classifi- cation and linguistic reconstruction. The aim of this paper is to present a con- cise application of both disciplines to the field of Bantu linguistics and to offer two interesting comparative case studies in the field of Bantu pottery vocabulary. The diachronic analysis of this lexical domain constitutes a promising field for interdisciplinary historical research. At the same time, the examples presented here urge history scholars to be cautious in the applica- tion of words-and-things studies for the use of historical reconstruction. The neglect of diachronic semantic evolutions and the impact of ancient lexical copies may lead to oversimplified and hence false historical conclusions. 2. Bantu languages and the synchronic nature of historical linguistics Exact estimations being complicated by the lack of good descriptive ma- terial, the Bantu languages are believed to number at present between 400 and 600. They are spoken in almost half of all sub-Saharan countries: Camer- 1 My acknowledgement goes to Yvonne Bastin, Claire Grégoire, Jacqueline Renard, Ellen Vandendorpe and Annemie Van Geldre who assisted me in the preparation of this paper. -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

Wr:X3,Clti: Lilelir)

ti:_Lilelir) 1^ (Dr\ wr:x3,cL KONINKLIJK MUSEUM MUSEE ROYAL DE VOOR MIDDEN-AFRIKA L'AFRIQUE CENTRALE TERVUREN, BELGIË TERVUREN, BELGIQUE INVENTARIS VAN INVENTAIRE DES HET HISTORISCH ARCHIEF VOL. 8 ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES LA MÉMOIRE DES BELGES EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE INVENTAIRE DES ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES PRIVÉES DU MUSÉE ROYAL DE L'AFRIQUE CENTRALE DE 1858 À NOS JOURS par Patricia VAN SCHUYLENBERGH Sous la direction de Philippe MARECHAL 1997 Cet ouvrage a été réalisé dans le cadre du programme "Centres de services et réseaux de recherche" pour le compte de l'Etat belge, Services fédéraux des affaires scientifiques, techniques et culturelles (Services du Premier Ministre) ISBN 2-87398-006-0 D/1997/0254/07 Photos de couverture: Recto: Maurice CALMEYN, au 2ème campement en . face de Bima, du 28 juin au 12 juillet 1907. Verso: extrait de son journal de notes, 12 juin 1908. M.R.A.C., Hist., 62.31.1. © AFRICA-MUSEUM (Tervuren, Belgium) INTRODUCTION La réalisation d'un inventaire des papiers de l'Etat ou de la colonie, missionnaires, privés de la section Histoire de la Présence ingénieurs, botanistes, géologues, artistes, belge Outre-Mer s'inscrit dans touristes, etc. - de leur famille ou de leurs l'aboutissement du projet "Centres de descendants et qui illustrent de manière services et réseaux de recherche", financé par extrêmement variée, l'histoire de la présence les Services fédéraux des affaires belge - et européenne- en Afrique centrale. scientifiques, techniques et culturelles, visant Quelques autres centres de documentation à rassembler sur une banque de données comme les Archives Générales du Royaume, informatisée, des témoignages écrits sur la le Musée royal de l'Armée et d'Histoire présence belge dans le monde et a fortiori, en militaire, les congrégations religieuses ou, à Afrique centrale, destination privilégiée de la une moindre échelle, les Archives Africaines plupart des Belges qui partaient à l'étranger. -

UNITED Nations Distr

UNITED NATiONS Distr. GENERAL SECURITY S/5053/Add.12 8 October 1962 COUNCIL ENGLISH ORIGINAL: ENGLISH/FRENCH REPORT TO THE SECRETARY-GENERAL FROM THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE OF THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN THE CONGO ON DEVELOPMENTS RELATING TO THE APPLICATION OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTIONS OF 21 FEBRUARY AND 24 NOVEMBER 1961 A. Build-Up of Katangese Mercenary Strength 1. In recent months) information has been received from various sources about a bUild-up in the strength of the Katanga armed forces) including the continued presence and some influx of foreign mercenaries. 2. It will be recalled that after the Kitona Declaration) signed on 21 December 1961 (S/5038 L Mr. Tshombe) President of the province of Katanga) made it clear to United Nations officials that he proposed to seek a solution to the mercenary problem "once and for all". This undertaking was put in writing in a letter dated 26 January 1962 to the United Nations representative in Elisabethville (S/5053/Add.3) Annex I)) and was repeated in a second letter dated 15 February 1962. 3. However) in spite of this and further declarations of Katangese spokesmen along the same lines as the above-mentioned letters) evidence ''las forthcon,ing to United. Nations authorities that in fact the pledge with regard to the elimination of mercenaries from Katanga was not being kept. 4. The ONUC-Katanga Joint Corrmissions on mercenaries) set up to certify that all foreign mercenaries had left Katanga in conformity with Mr. Tshombe's decision) visited Jadotville and Kipushi on 9 February 1962) and Kolwezi and Bunkeya on 21--23 February. -

IMPACTS of CLIMATE CHANGE on WATER AVAILABILITY in ZAMBIA: IMPLICATIONS for IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENT By

Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research Paper 146 August 2019 IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON WATER AVAILABILITY IN ZAMBIA: IMPLICATIONS FOR IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENT By Byman H. Hamududu and Hambulo Ngoma Food Security Policy Research Papers This Research Paper series is designed to timely disseminate research and policy analytical outputs generated by the USAID funded Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy (FSP) and its Associate Awards. The FSP project is managed by the Food Security Group (FSG) of the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE) at Michigan State University (MSU), and implemented in partnership with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the University of Pretoria (UP). Together, the MSU-IFPRI-UP consortium works with governments, researchers and private sector stakeholders in Feed the Future focus countries in Africa and Asia to increase agricultural productivity, improve dietary diversity and build greater resilience to challenges like climate change that affect livelihoods . The papers are aimed at researchers, policy makers, donor agencies, educators, and international development practitioners. Selected papers will be translated into French, Portuguese, or other languages. Copies of all FSP Research Papers and Policy Briefs are freely downloadable in pdf format from the following Web site: https://www.canr.msu.edu/fsp/publications/ Copies of all FSP papers and briefs are also submitted to the USAID Development Experience Clearing House (DEC) at: http://dec.usaid.gov/ ii AUTHORS: Hamududu is Senior Engineer, Water Balance, Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Oslo, Norway and Ngoma is Research Fellow, Climate Change and Natural Resources, Indaba Agricultural Policy Research Institute (IAPRI), Lusaka, Zambia and Post-Doctoral Research Associate, Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. -

Masterproef Maxim Veys 20055346

Universiteit Gent – Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Race naar Katanga 1890-1893. Een onderzoek naar het organisatorische karakter van de expedities in Congo Vrijstaat 1890-1893. Scriptie voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad van Master in de Geschiedenis Vakgroep Nieuwste Geschiedenis Academiejaar: 2009-2010 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Eric Vanhaute Maxim A. Veys Dankwoord Deze thesis was een werk van lange adem. Daarom zou ik graag mijn dank betuigen aan enkele mensen. Allereerst zou ik graag mijn promotor, Prof. Dr. Eric Vanhaute, willen bedanken voor de bereidheid die hij had om mij te begeleiden bij dit werk. In het bijzonder wil ik ook graag Jan-Frederik Abbeloos, assistent op de vakgroep, bedanken voor het aanleveren van het eerste idee en interessante extra literatuur, en het vele geduld dat hij met mij heeft gehad. Daarnaast dien ik ook mijn ouders te bedanken. In de eerste plaats omdat zij mij de kans hebben gegeven om deze opleiding aan te vatten, en voor de vele steun in soms lastige momenten. Deze scriptie mooi afronden is het minste wat ik kan doen als wederdienst. Ook het engelengeduld van mijn vader mag ongetwijfeld vermeld worden. Dr. Luc Janssens en Alexander Heymans van het Algemeen Rijksarchief wens ik te vermelden voor hun belangrijke hulp bij het recupereren van verloren gewaande bronnen, cruciaal om deze verhandeling te kunnen voltooien. Ik wil ook Sara bedanken voor het nalezen van mijn teksten. Maxim Veys 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE Voorblad 1 Dankwoord 2 Inhoudsopgave 3 I. Inleiding 4 II. Literatuurstudie 13 1. Het nieuwe imperialisme 13 2. Het Belgische “imperialisme” 16 3. De Onafhankelijke Congostaat. -

Gaston Renard Books Australasia

CATALOGUE NUMBER 392 A Miscellany: AUSTRALIANA, ASIA, HISTORY, THE PACIFIC REGION; BOOKS ON BOOKS, PRINTING AND TYPOGRAPHY; VOYAGES & TRAVELS, EXPLORATION, &c. GASTON RENARD BOOKS AUSTRALASIA Fine and Rare Books P.O. Box 1030, IVANHOE, Victoria, 3079, Australia. Website: http://www.GastonRenard.com.au Email: [email protected] Telephone: (+61 3) 9459 5040 FAX: (+61 3) 9459 6787 2009 NOTES AND CONDITIONS OF SALE. We want you to order books from this catalogue and to be completely satisfied with your purchase so that you will order again in future. Please take a moment to read these notes explaining our service and our Conditions of Sale. 1. All books in this and other catalogues issued by us have been examined in detail and are guaranteed to be complete and in good condition unless otherwise stated; all defects are fully and fairly described. All secondhand books we offer for sale have been collated page by page in order to find such defects or verify that there are none. We suggest however, that as a matter of course, you should carry out your own checks of all purchases from whatever source. 2. You may return books for any reason, however such returns must be made within 3 days of receipt and postage paid in both directions unless we are at fault in which case we will pay all postage charges. You should notify us immediately of your intention to return and we would appreciate you informing us of the reason. Books returned should also be properly packed. It is a condition of return that you accept liability for any damage occurring during transit. -

Liberia Author(S): Harry Johnston Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

Liberia Author(s): Harry Johnston Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Aug., 1905), pp. 131-151 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1776207 Accessed: 25-06-2016 03:48 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 132.239.1.230 on Sat, 25 Jun 2016 03:48:36 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms LIBERIA. 131 than this year, while some have even held that it is earlier than the Rome edition. The modern maps are those of Spain, France, Italy, and the Holy Land, and already show considerable progress towards a correct delineation of the outlines of these countries. Of later editions of Ptolemy, Dr. Peckover has presented copies of the Strassburg edition of 1520 (the second issue with Waldseemiiller's maps); the Venice edition of 1561 (the first Italian translation, by Ruscelli, from the original Greek, with maps based on Gastaldi's); the Cologne edition of 1606 (third of Magini in Latin); and the fine Elzevir edition of 1618, by Bertius, with Mercator's maps, the Peutinger table, etc. -

A History of Nairobi, Capital of Kenya

....IJ .. Kenya Information Dept. Nairobi, Showing the Legislative Council Building TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Chapter I. Pre-colonial Background • • • • • • • • • • 4 II. The Nairobi Area. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 29 III. Nairobi from 1896-1919 •• • • • • • • • • • 50 IV. Interwar Nairobi: 1920-1939. • • • • • • • 74 V. War Time and Postwar Nairobi: 1940-1963 •• 110 VI. Independent Nairobi: 1964-1966 • • • • • • 144 Appendix • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 168 Bibliographical Note • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 179 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 182 iii PREFACE Urbanization is the touchstone of civilization, the dividing mark between raw independence and refined inter dependence. In an urbanized world, countries are apt to be judged according to their degree of urbanization. A glance at the map shows that the under-developed countries are also, by and large, rural. Cities have long existed in Africa, of course. From the ancient trade and cultural centers of Carthage and Alexandria to the mediaeval sultanates of East Africa, urban life has long existed in some degree or another. Yet none of these cities changed significantly the rural character of the African hinterland. Today the city needs to be more than the occasional market place, the seat of political authority, and a haven for the literati. It remains these of course, but it is much more. It must be the industrial and economic wellspring of a large area, perhaps of a nation. The city has become the concomitant of industrialization and industrialization the concomitant 1 2 of the revolution of rising expectations. African cities today are largely the products of colonial enterprise but are equally the measure of their country's progress. The city is witness everywhere to the acute personal, familial, and social upheavals of society in the process of urbanization. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011).