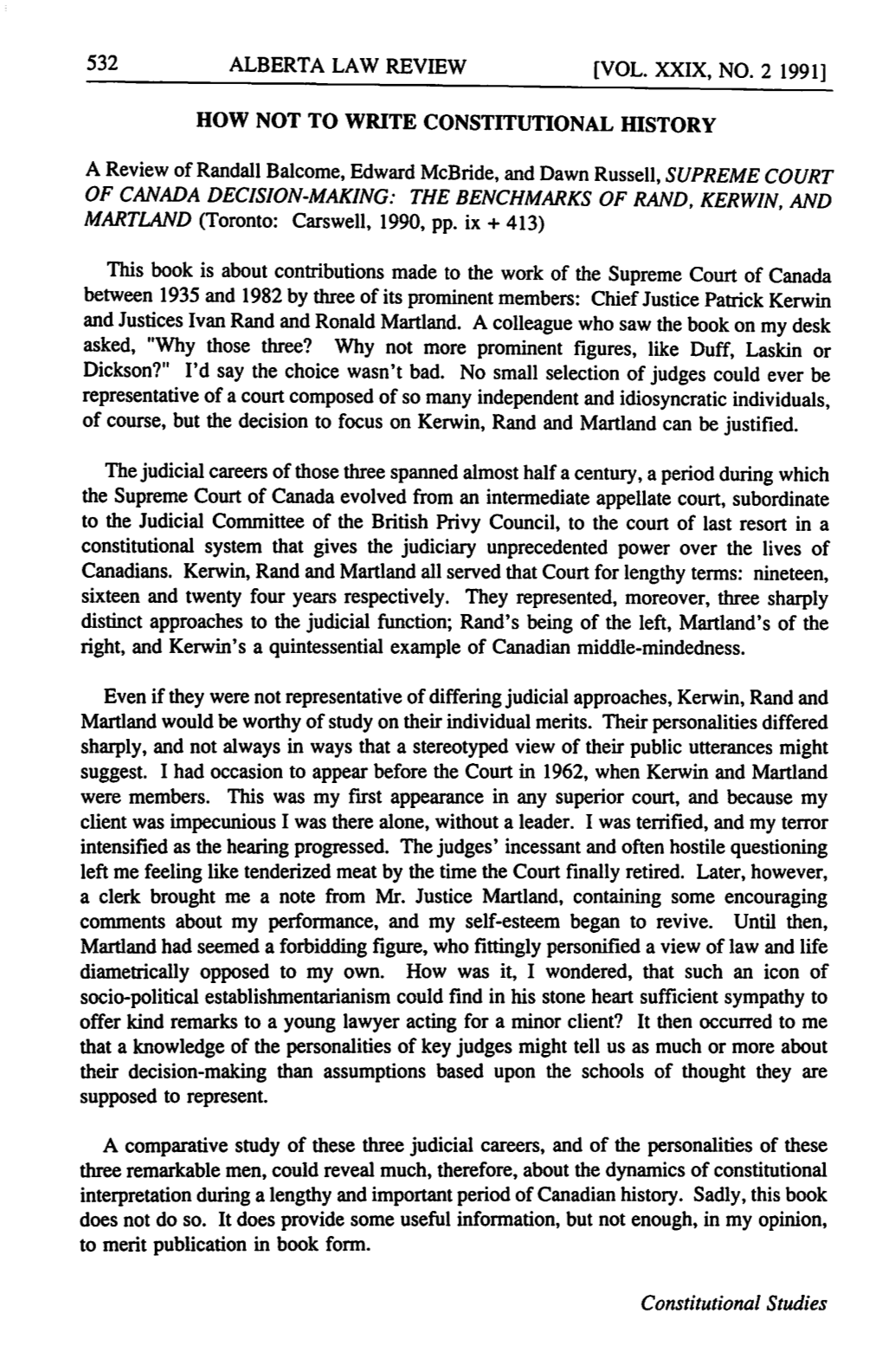

HOW NOT to WRITE CONSTITUTIONAL Mstory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social Contract

The Social Contract Expression Graphics | March 2013 University of Western Ontario (London, Ontario) The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. Its contents do not reflect the opinion of the University Students’ Council of the University of Western Ontario (“USC”). The USC assumes no responsibility or liability for any error, inaccuracy, omission or comment contained in this publication or for any use that may be made of such information by the reader. -1- Table of Contents Preface 3 Letter from the Editor 4 Editorial Board and Staff 5 Special Thanks 6 POLITICAL THEORY War in the Name of Humanity: Liberal Cosmopolitanism and the Depoliticization 9 of the War on Terror by Monica Kozycz Restitutive Justice: The Key to Social Equality by Philip Henderson 23 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Vacillating on Darfur: Achieving Peace and Security in Sudan’s Forsaken West 34 by Larissa Fulop Symbol or Strategic Constraint?: The Implications of the EU Arms Embargo 49 for EU-China Relations and China’s Strategy by Ross Linden-Fraser COMPARATIVE POLITICS Mandatory Minimum Drug Sentences by Robert Salvatore Powers 68 CANADIAN POLITICS The Fight to Regain Indigenous Self-Determination in Canada by Philip Henderson 82 AMERICAN POLITICS American Constitutionalism and International Human Rights: A Legal Perspective 94 by Jeremy Luedi BUSINESS AND GOVERNANCE New Public Management, Public-Private Partnerships and Ethical Conflicts 111 for Civil Servants by André Paul Wilkie Implications of Right-to-Work Legislation in Ontario by Caitlin Dunn 126 IDENTITY POLITICS Race and Romance: Black-White Interracial Relationships since Loving v. Virginia 141 by Monica Kozycz MEDIA AND POLITICS More of the Same: The Internet’s Role in Political Campaigns 154 by Steven Wright -2- Preface On behalf of the Department of Political Science, I am both happy and proud to congratulate you on publishing this year’s issue of The Social Contract. -

Legality As Reason: Dicey, Rand, and the Rule of Law

McGill Law Journal ~ Revue de droit de McGill LEGALITY AS REASON: DICEY, RAND, AND THE RULE OF LAW Mark D. Walters* For many law students in Canada, the Pour bon nombre d’étudiants en droit au idea of the rule of law is associated with the Canada, l’idée d’une primauté du droit est asso- names of Professor A.V. Dicey, Justice Ivan ciée au professeur A.V. Dicey et au juge Ivan Rand, and the case of Roncarelli v. Duplessis. It Rand ainsi qu’à l’affaire Roncarelli c. Duplessis. is common for students to read excerpts from Il est courant pour les étudiants de lire des ex- Dicey’s Law of the Constitution on the rule of traits traitant de la primauté du droit dans law, and then to examine how the rule of law is, l’œuvre de Dicey intitulée Law of the Constitu- as Rand stated in Roncarelli, “a fundamental tion, puis d’examiner comment la primauté du postulate of our constitutional structure.” In- droit est, comme l’a affirmé Rand dans Ronca- deed, Roncarelli marked a point in time, fifty relli, « [l’]un des postulats fondamentaux de no- years ago, at which the academic expression tre structure constitutionnelle ». En effet, l’arrêt “the rule of law” became a meaningful part of Roncarelli a été rendu au moment où, il y a cin- the legal discourse of judges and lawyers in quante ans, l’expression académique « la pri- Canada. mauté du droit » s’intégrait au sein du discours In this article, the author considers the re- des juges et des avocats au Canada. -

An Unlikely Maverick

CANADIAN MAVERICK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF IVAN C. RAND 795 “THE MAVERICK CONSTITUTION” — A REVIEW OF CANADIAN MAVERICK: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF IVAN C. RAND, WILLIAM KAPLAN (TORONTO: UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS FOR THE OSGOODE SOCIETY FOR CANADIAN LEGAL HISTORY, 2009) When a man has risen to great intellectual or moral eminence; the process by which his mind was formed is one of the most instructive circumstances which can be unveiled to mankind. It displays to their view the means of acquiring excellence, and suggests the most persuasive motive to employ them. When, however, we are merely told that a man went to such a school on such a day, and such a college on another, our curiosity may be somewhat gratified, but we have received no lesson. We know not the discipline to which his own will, and the recommendation of his teachers subjected him. James Mill1 While there is today a body of Canadian constitutional jurisprudence that attracts attention throughout the common law world, one may not have foreseen its development in 1949 — the year in which appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (Privy Council) were abolished and the Supreme Court of Canada became a court of last resort. With the exception of some early decisions regarding the division of powers under the British North America Act, 1867,2 one would be hard-pressed to characterize the Supreme Court’s record in the mid-twentieth century as either groundbreaking or original.3 Once the Privy Council asserted its interpretive dominance over the B.N.A. -

FORFEITED Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution

FORFEITED Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution by Joshua Alan Krane A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Graduate Department of the Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Joshua Alan Krane (2010) FORFEITED Civil Forfeiture and the Canadian Constitution Joshua Alan Krane, B.Soc.Sc., B.C.L/LL.B. Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2010 Abstract The enactment of civil asset forfeiture legislation by Alberta and Ontario in the fall of 2001, followed by the passage of similar legislation in five other provinces, has signalled a dramatic change in the way Canadian constitutional law ought to be understood. This thesis builds on American legal scholarship by highlighting how deficiencies in Canada’s constitutional law could create space for more inva- sive civil forfeiture statutes. Following a historical overview of forfeiture law in Canada, the thesis (i) examines how the Supreme Court of Canada mischaracter- ized this legislation as a matter of property and civil rights; (ii) considers whether the doctrine of federal paramountcy should have rendered the legislation inoper- able and the consequences of the failure by the Court to do so; and (iii) evaluates -ii- the impact of the absence of an entrenched property right in the constitution, in regard to this matter. -iii- Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................. 1 The Aim of this Project.............................................................................. -

A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962

8 A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962 When the newly paramount Supreme Court of Canada met for the first timeearlyin 1950,nothing marked theoccasionasspecial. ltwastypicalof much of the institution's history and reflective of its continuing subsidiary status that the event would be allowed to pass without formal recogni- tion. Chief Justice Rinfret had hoped to draw public attention to the Court'snew position throughanotherformalopeningofthebuilding, ora reception, or a dinner. But the government claimed that it could find no funds to cover the expenses; after discussing the matter, the cabinet decided not to ask Parliament for the money because it might give rise to a controversial debate over the Court. Justice Kerwin reported, 'They [the cabinet ministers] decided that they could not ask fora vote in Parliament in theestimates tocoversuchexpensesas they wereafraid that that would give rise to many difficulties, and possibly some unpleasantness." The considerable attention paid to the Supreme Court over the previous few years and the changes in its structure had opened broader debate on aspects of the Court than the federal government was willing to tolerate. The government accordingly avoided making the Court a subject of special attention, even on theimportant occasion of itsindependence. As a result, the Court reverted to a less prominent position in Ottawa, and the status quo ante was confirmed. But the desire to avoid debate about the Court discouraged the possibility of change (and potentially of improvement). The St Laurent and Diefenbaker appointments during the first decade A Decade of Adjustment 197 following termination of appeals showed no apparent recognition of the Court’s new status. -

Architypes Vol. 15 Issue 1, 2006

ARCHITYPES Legal Archives Society of Alberta Newsletter Volume 15, Issue I, Summer 2006 Prof. Peter W. Hogg to speak at LASA Dinners. Were rich, we have control over our oil and gas reserves and were the envy of many. But it wasnt always this way. Instead, the story behind Albertas natural resource control is one of bitterness and struggle. Professor Peter Hogg will tell us of this Peter W. Hogg, C.C., Q.C., struggle by highlighting three distinct periods in Albertas L.S.M., F.R.S.C., scholar in history: the provinces entry into Confederation, the Natural residence at the law firm of Resource Transfer Agreement of 1930, and the Oil Crisis of the Blake, Cassels & Graydon 1970s and 1980s. Its a cautionary tale with perhaps a few LLP. surprises, a message about cooperation and a happy ending. Add in a great meal, wine, silent auction and legal kinship and it will be a perfect night out. Peter W. Hogg was a professor and Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School at York University from 1970 to 2003. He is currently scholar in residence at the law firm of Blake, Cassels & Canada. Hogg is the author of Constitutional Law of Canada Graydon LLP. In February 2006 he delivered the opening and (Carswell, 4th ed., 1997) and Liability of the Crown (Carswell, closing remarks for Canadas first-ever televised public hearing 3rd ed., 2000 with Patrick J. Monahan) as well as other books for the review of the new nominee for the Supreme Court of and articles. He has also been cited by the Supreme Court of Canada more than twice as many times as any other author. -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

Mr. Justice Rand a Triumph of Principle

MR. JUSTICE RAND A TRIUMPH OF PRINCIPLE E. MARSHALL POLLOCK* Toronto Introduction Ivan Cleveland Rand- was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada on April 22nd, 1943 in his fifty-ninth year. It would be more accurate to say that he was drafted into the court. His reputation as a man of principle, an independent thinker, and an outstanding lawyer, had preceded him to Ottawa . Rand's appoint- ment to the court, like the universal respect which he enjoyed,, had commanded itself. The purpose of this article, written as the Supreme Court of Canada celebrates its centenary, is to attempt an assessment of Rand's contribution to that institution and the effect of that contribution on the court and on Canadian jurisprudence. In Rand, we are fortunate to have a subject who has written and lectured extensively, thereby leaving a record which supplements his judicial pronouncements and which lends valuable insight into his thought processes. To paraphrase the time-worn admonition to counsel, he told us what he was going to do, he did it, and he told us what he did, even in the doing. The son of a railway mechanic, Rand spent five years in the audit office of the Intercolonial Railway before pursuing his university studies at Mount Allison University. In Rand's valedic tory address of 1909 we find not only a message to his fellow graduates but the. earliest articulation of the credo by which he lived, was judged and-what became very significant in his later years-by which he judged others. It was for Ivan Rand the universal filter through which his whole life passed : The honesty, the courtesy, the dignity, the flush of modesty, the purity of thought, these are characteristics which are not the exclusive property of the possessor. -

Ian Holloway*

“yoU MUst Learn to see Life steady and whoLe”: ivan cLeveLand rand and LegaL edUcation Ian Holloway* IVAN RAND: A MAN AND HIS TIMES To understand properly Ivan Rand’s views on legal education, just as to understand 2010 CanLIIDocs 228 properly his jurisprudence, it is critical to appreciate that he was born a Victorian and came of age an Edwardian. He came to national prominence in the Atomic Age – in the middle part of the twentieth century – but he was born in 1884, in the midst of the Mahdi’s Rebellion in the Sudan and a year before the Riel Rebellion in the old Red River Territory. His birth took place in the same year that the British Parliament enacted the Third Reform Bill,1 and only two years after the Married Women’s Property Act came into force.2 Rand was sixteen when Queen Victoria died and, while old enough to have enlisted in the Canadian battalions that fought in the Boer War, he was too old to serve in the First World War. He was thirty years of age when the “Guns of August” started and almost thirty-five when they fell silent in November 1918. To consider Ivan Rand in this context can seem not a little startling, for we – at least those of us who are not students of the political history of the Maritime Provinces or of the Canadian National Railway – tend to think of him in terms of * Dean and Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Western Ontario I acknowledge the assistance given me in this project by my old colleague at the firm of McInnes Cooper, Eric LeDrew, and his articled clerk, Allan White. -

Ian Bushnell*

JUstice ivan rand and the roLe of a JUdge in the nation’s highest coUrt Ian Bushnell* INTRODUCTION What is the proper role for the judiciary in the governance of a country? This must be the most fundamental question when the work of judges is examined. It is a constitutional question. Naturally, the judicial role or, more specifically, the method of judicial decision-making, critically affects how lawyers function before the courts, i.e., what should be the content of the legal argument? What facts are needed? At an even more basic level, it affects the education that lawyers should experience. The present focus of attention is Ivan Cleveland Rand, a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1943 until 1959 and widely reputed to be one of the greatest judges on that Court. His reputation is generally based on his method of decision-making, a method said to have been missing in the work of other judges of his time. The Rand legal method, based on his view of the judicial function, placed him in illustrious company. His work exemplified the traditional common law approach as seen in the works of classic writers and judges such as Sir Edward Coke, Sir Matthew Hale, Sir William Blackstone, and Lord Mansfield. And he was in company with modern jurists whose names command respect, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Benjamin Cardozo, as well as a law professor of Rand at Harvard, Roscoe Pound. In his judicial decisions, addresses and other writings, he kept no secrets about his approach and his view of the judicial role. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

Co Supreme Court of Canada

supreme court of canada of court supreme cour suprême du canada Philippe Landreville unless otherwise indicated otherwise unless Landreville Philippe by Photographs Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0J1 K1A Ontario Ottawa, 301 Wellington Street Wellington 301 Supreme Court of Canada of Court Supreme ISBN 978-1-100-21591-4 ISBN JU5-23/2013E-PDF No. Cat. ISBN 978-1-100-54456-4 ISBN Cat. No. JU5-23/2013 No. Cat. © Supreme Court of Canada (2013) Canada of Court Supreme © © Cour suprême du Canada (2013) No de cat. JU5-23/2013 ISBN 978-1-100-54456-4 No de cat. JU5-23/2013F-PDF ISBN 978-0-662-72037-9 Cour suprême du Canada 301, rue Wellington Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0J1 Sauf indication contraire, les photographies sont de Philippe Landreville. SUPREME COURT OF CANADA rom the quill pen to the computer mouse, from unpublished unilingual decisions to Internet accessible bilingual judgments, from bulky paper files to virtual electronic documents, the Supreme Court of Canada has seen tremendous changes from the time of its inception and is now well anchored in the 21st century. Since its establishment in 1875, the Court has evolved from being a court of appeal whose decisions were subject to review by a higher authority in the United Kingdom to being the final court of appeal in Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada deals with cases that have a significant impact on Canadian society, and its judgments are read and respected by Canadians and by courts worldwide. This edition of Supreme Court of Canada marks the retirement of Madam Justice Marie Deschamps, followed by Fthe recent appointment of Mr.