Reproduction of Authentic Historical Soft Iron Wire for Musical Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1785-1998 September 1998

THE EVOLUTION OF THE BROADWOOD GRAND PIANO 1785-1998 by Alastair Laurence DPhil. University of York Department of Music September 1998 Broadwood Grand Piano of 1801 (Finchcocks Collection, Goudhurst, Kent) Abstract: The Evolution of the Broadwood Grand Piano, 1785-1998 This dissertation describes the way in which one company's product - the grand piano - evolved over a period of two hundred and thirteen years. The account begins by tracing the origins of the English grand, then proceeds with a description of the earliest surviving models by Broadwood, dating from the late eighteenth century. Next follows an examination of John Broadwood and Sons' piano production methods in London during the early nineteenth century, and the transition from small-scale workshop to large factory is noted. The dissertation then proceeds to record in detail the many small changes to grand design which took place as the nineteenth century progressed, ranging from the extension of the keyboard compass, to the introduction of novel technical features such as the famous Broadwood barless steel frame. The dissertation concludes by charting the survival of the Broadwood grand piano since 1914, and records the numerous difficulties which have faced the long-established company during the present century. The unique feature of this dissertation is the way in which much of the information it contains has been collected as a result of the writer's own practical involvement in piano making, tuning and restoring over a period of thirty years; he has had the opportunity to examine many different kinds of Broadwood grand from a variety of historical periods. -

Ellen Fullman

A Compositional Approach Derived from Material and Ephemeral Elements Ellen Fullman My primary artistic activity has been focused coffee cans with large metal mix- around my installation the Long String Instrument, in which ing bowls filled with water and rosin-coated fingers brush across dozens of metallic strings, rubbed the wires with my hands, ABSTRACT producing a chorus of minimal, organ-like overtones, which tipping the bowl to modulate the The author discusses her has been compared to the experience of standing inside an sound. I wanted to be able to tune experiences in conceiving, enormous grand piano [1]. the wire, but changing the tension designing and working with did nothing. I knew I needed help the Long String Instrument, from an engineer. At the time I was an ongoing hybrid of installa- BACKGROUND tion and instrument integrat- listening with great interest to Pau- ing acoustics, engineering In 1979, during my senior year studying sculpture at the Kan- line Oliveros’s album Accordion and and composition. sas City Art Institute, I became interested in working with Voice. I could imagine making mu- sound in a concrete way using tape-recording techniques. This sic with this kind of timbre, playing work functioned as soundtracks for my performance art. I also created a metal skirt sound sculpture, a costume that I wore in which guitar strings attached to the toes and heels of my Fig. 1. Metal Skirt Sound Sculpture, 1980. (© Ellen Fullman. Photo © Ann Marsden.) platform shoes and to the edges of the “skirt” automatically produced rising and falling glissandi as they were stretched and released as I walked (Fig. -

Andrew Nolan Viennese

Restoration report South German or Austrian Tafelklavier c. 1830-40 Andrew Nolan, Broadbeach, Queensland. copyright 2011 Description This instrument is a 6 1/2 octave (CC-g4) square piano of moderate size standing on 4 reeded conical legs with casters, veneered in bookmatched figured walnut in Biedermeier furniture style with a single line of inlaid stringing at the bottom of the sides and a border around the top of the lid. This was originally stained red to resemble mahogany and the original finish appearance is visible under the front lid flap. The interior is veneered in bookmatched figured maple with a line of dark stringing. It has a wrought iron string plate on the right which is lacquered black on a gold base with droplet like pattern similar to in concept to the string plates of Broadwood c 1828-30. The pinblock and yoke are at the front of the instrument over the keyboard as in a grand style piano and the bass strings run from the front left corner to the right rear corner. The stringing is bichord except for the extreme bass CC- C where there are single overwound strings, and the top 1 1/2 octaves of the treble where there is trichord stringing. The top section of the nut for the trichords is made of an iron bar with brass hitch pins inserted at the top, this was screwed and glued to the leading edge of the pinblock. There is a music rack of walnut which fits into holes in the yoke. The back of this rack is hinged in the middle and at the bottom. -

Piano Manufacturing an Art and a Craft

Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Gesa Lücker (Concert pianist and professor of piano, University for Music and Drama, Hannover) Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Since time immemorial, music has accompanied mankind. The earliest instrumentological finds date back 50,000 years. The first known musical instrument with fibers under ten sion serving as strings and a resonator is the stick zither. From this small beginning, a vast array of plucked and struck stringed instruments evolved, eventually resulting in the first stringed keyboard instruments. With the invention of the hammer harpsichord (gravi cembalo col piano e forte, “harpsichord with piano and forte”, i.e. with the capability of dynamic modulation) in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, the pianoforte was born, which over the following centuries evolved into the most versitile and widely disseminated musical instrument of all time. This was possible only in the context of the high level of devel- opment of artistry and craftsmanship worldwide, particu- larly in the German-speaking part of Europe. Since 1885, the Schimmel family has belonged to a circle of German manufacturers preserving the traditional art and craft of piano building, advancing it to ever greater perfection. Today Schimmel ranks first among the resident German piano manufacturers still owned and operated by Contents the original founding family, now in its fourth generation. Schimmel pianos enjoy an excellent reputation worldwide. 09 The Fascination of the Piano This booklet, now in its completely revised and 15 The Evolution of the Piano up dated eighth edition, was first published in 1985 on The Origin of Music and Stringed Instruments the occa sion of the centennial of Wilhelm Schimmel, 18 Early Stringed Instruments – Plucked Wood Pianofortefa brik GmbH. -

Voices of the Electric Guitar

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Voices of the electric guitar Don Curnow California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Curnow, Don, "Voices of the electric guitar" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 369. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/369 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Voices of the Electric Guitar Don Curnow MPA 475 12-12-12 Intro The solid body electric guitar is the result of many guitars and innovations that came before it, followed by the guitar's need for volume to compete with louder instruments, particularly when soloing. In the 1930s, jazz and its various forms incorporated the guitar, but at the time there was no way for an acoustic guitar to compete with the volume of a trumpet or saxophone, let alone with an orchestra of trumpets and saxophones, such as in big band jazz. As a result, amplification of the guitar was born and the electric guitar has been evolving since, from a hollow bodied ES-150 arch-top with a pick-up used by Charlie Christian to the Les Paul played by Slash today. -

HTMA President's Notes

Volume 46, Issue 5 www.huntsvillefolk.org May 2012 Next Meeting May 20th TheHTMA Huntsville President’s Traditional NotesMusic Association meets on the third Sunday of 2:00 P.M. Huntsville/Madison Public Library As I write this eachI’m missingmonth the April HTMA coffeehouse –Our once next again meeting duty calledis: me out of HTMA town on Sunday,the wrong February week. I’m 21st getting pretty coffeehouse Music Series envious of all my friends in the association who 2:00 - 4:30 PM Presents has retired from their day jobs. Not that I mind working Huntsville/Madison so much, but PublicI’d sure Library like toAuditorium have a little more time to play. I haven’t totally missed out on music, though. Last weekend Ginny and I travelled over to my brother’s house for a “Tuneful Friday” celebration. http://www.bryanbowers.com/What a collection of terrific musicians came over that night! I spent a fair amount of time that night holding my guitar very quietly – no way I was going to keep up with some of th ose guys. As usual in a gathering of musicians, everyone was very supportive – the best players and the hacks like me all got a nice round of applause after every tune. All of a sudden it was past midnight and folks May 24th remembered that they weren’t going to be able to 7:00 PM sleep in Saturday, and we had to pack it in. I don’t know how the evening passed so quickly. (continued on page 4) Old Country Church Inside this Issue: Page 1: President’s Notes Page 2: May Area Events / Executive Board Page 3: The Berry Patch Page 4: President’s Notes Cont. -

Ryokoakamaexploringemptines

University of Huddersfield Repository Akama, Ryoko Exploring Empitness: An Investigation of MA and MU in My Sonic Composition Practice Original Citation Akama, Ryoko (2015) Exploring Empitness: An Investigation of MA and MU in My Sonic Composition Practice. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/26619/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ EXPLORING EMPTINESS AN INVESTIGATION OF MA AND MU IN MY SONIC COMPOSITION PRACTICE Ryoko Akama A commentary accompanying the publication portfolio submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! The University of Huddersfield School of Music, Humanities and Media April, 2015 Title: Exploring Emptiness Subtitle: An investigation of ma and mu in my sonic composition practice Name of student: Ryoko Akama Supervisor: Prof. -

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

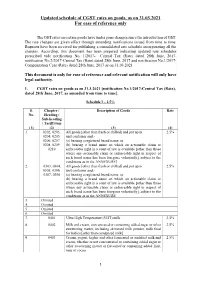

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

Sine Waves and Simple Acoustic Phenomena in Experimental Music - with Special Reference to the Work of La Monte Young and Alvin Lucier

Sine Waves and Simple Acoustic Phenomena in Experimental Music - with Special Reference to the Work of La Monte Young and Alvin Lucier Peter John Blamey Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my principal supervisor Dr Chris Fleming for his generosity, guidance, good humour and invaluable assistance in researching and writing this thesis (and also for his willingness to participate in productive digressions on just about any subject). I would also like to thank the other members of my supervisory panel - Dr Caleb Kelly and Professor Julian Knowles - for all of their encouragement and advice. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .......................................................... (Signature) Table of Contents Abstract..................................................................................................................iii Introduction: Simple sounds, simple shapes, complex notions.............................1 Signs of sines....................................................................................................................4 Acoustics, aesthetics, and transduction........................................................................6 The acoustic and the auditory......................................................................................10 -

Agenda for 21 GST Council Meeting

Confidential Agenda for 21st GST Council Meeting 9 September 2017 Hyderabad, Telangana Page 2 of 173 F.No. 144/21st Meeting/GST Council/2017 GST Council Secretariat Room No.275, North Block, New Delhi Dated: 5 September 2017 Notice for the 21st Meeting of the GST Council on 9 September 2017 The undersigned is directed to refer to the subject cited above and to say that the 21st meeting of the GST Council will be held on 9 September 2017 at Hyderabad International Convention Centre, Novotel Hotel, Madhapur, Hyderabad. The schedule of the meeting is as follows: i. Saturday, 9 September 2017 : 1100 hours onwards 2. In addition, an officers’ meeting will be held at the same venue as per the following schedule: ii. Friday, 8 September 2017 : 1500 hours onwards 3. The agenda items for the 21st GST Council Meeting are attached. 4. Keeping in view the constraints of rooms in the hotel, it is requested that participation from each State may be limited to 2 officers in addition to the Hon’ble Member of the GST Council. 5. Please convey the invitation to the Hon’ble Members of the GST Council to attend the 21st GST Council Meeting. - Sd - (Dr. Hasmukh Adhia) Secretary to the Govt. of India and ex-officio Secretary to the GST Council Tel: 011 23092653 Copy to: 1. PS to the Hon’ble Minister of Finance, Government of India, North Block, New Delhi with the request to brief Hon’ble Minister about the above said meeting. 2. PS to Hon’ble Minister of State (Finance), Government of India, North Block, New Delhi with the request to brief Hon’ble Minister about the above said meeting. -

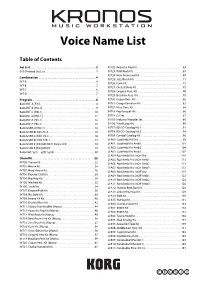

KRONOS Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Set List. .3 INT22: Acoustic Pop Kit . .65 000: Preload Set List. 3 INT23: Wild Rock Kit . .67 INT24: New Processed Kit . .69 Combination . .4 INT25: Jazz/Brush Kit . .71 INT-A . 4 INT26: Funk Kit . .73 INT-B . 5 INT27: Orch./Ethnic Kit. .75 INT-C . 6 INT28: Original Perc. Kit. .76 INT-D . 7 INT29: Brazilian Perc. Kit . .78 Program . .8 INT30: Cuban Perc. Kit . .80 Bank INT-A [EXi]. 8 INT31: Conga Variation Kit . .82 Bank INT-B [HD-1]. 9 INT32: Misc. Perc. Kit. .84 Bank INT-C [HD-1]. 10 INT33: Rap/Gospel Hits . .86 Bank INT-D [HD-1] . 11 INT34: DJ Set . .87 Bank INT-E [HD-1] . 12 INT35: Industry/VocoderSet. .88 Bank INT-F [HD-1] . 13 INT36: Vinyl Loop Kit . .89 Bank USER-A [HD-1]. 14 INT37: BD/SD Catalog Kit 1. .91 Bank USER-B [EXi] AL-1 . 15 INT38: BD/SD Catalog Kit 2. .94 Bank USER-C [EXi] CX-3. 16 INT39: Cymbal Catalog Kit . .96 Bank USER-D [EXi] STR-1. 17 U-A00: JazzAmbi Kit Dry . .98 Bank USER-E [EXi] MS20EX, Polysix EX. 18 U-A01: JazzAmbi Kit Amb1. .101 Bank USER-F [EXi] MOD7 . 19 U-A02: JazzAmbi Kit Amb2. .104 Bank GM / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 20 U-A03: JazzAmbi Kit Amb3. .107 U-A04: RockAmbi Kit SnOn Dry . .110 Drum Kit . 22 U-A05: RockAmbi Kit SnOn Amb1 . .113 INT00: Trance kit . 22 U-A06: RockAmbi Kit SnOn Amb2 . .115 INT01: House Kit . -

THE WIRE HARP SFCC 2016 Wire Harp Staff

2016 2016 THE WIRE HARP SFCC 2016 Wire Harp Staff Graphic Arts Editor: Jeremy King Graphic Arts Advisor: Doug Crabtree Literary Editor: Zach Bartmess Literary Staff: Ryan Hatten Lindsy Kay Venessa Rowley Laura Stephenson Literary Advisors: Laura Read and Connie Wasem Scott Special Thanks: Richard Baldasty, Heather McKenzie, Shelli Cockle, Bonnie Brunt, Carl Richardson, Erik Sohner, Craig Rickett, Lloydeen Jensen, and Becky Turner. Cover Illustration: Christian Davenny ii Wire Harp 2016 Richard Baldasty Awards Wire Harp Awards Richard Baldasty taught philosophy and history at SFCC from 1984-2007, and during his tenure, he was regularly published in this journal and contributed significantly to the arts on our campus. Upon his retirement, the Wire Harp honored the spotlight he shone on art by naming our poetry award for him. Each year, Wire Harp staff selects what we consider the most artistic poem as the recipient of this award. We also honor a work of prose, a photograph, and a work of fine art. Each of these four student artists receives a $100 prize, as a result of a generous gift from Richard. We appreciate Richard for supporting students in their creative arts. 2016 Wire Harp iii Contents Poetry Come Downstairs . 3. The Absent Table . 88 Luke Roe K.G. Brown 1991 . .6 Hangman Golf Course . .92 Tim Greenup Jonni Deakins Gotta Quick Second? Because the Ice Still Haunts Your Ten Haikus for your Pleasure Dreams . .95 From Tyler to You . 11 Nyirenda Ross Tyler Pursch Peach Wine and Fireworks . .96 It Must Be Like This . 14 Ryan Hatten Carol Harrington Supernova .