Development of the Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index (Complete)

Sample page from Pianos Inside Out. Copyright © 2013 Mario Igrec. 527 Index composite parts 375 rails, repairing 240 facing off 439 Numerics compressed 68 rebuilding, overview 325 grooved, effects on tuning 132 105 System 336 diagram 64 regulating 166 reducing height of 439 16th Tone Piano 94 Double Repetition in verticals 77 regulating on the bench 141 replacing 436 1867 Exposition in Paris 13 double-escapement 5, 12 regulation, effects on tuning 129 to rebuild or replace 326 3M 267, 338 dropped 68, 113, 140, 320 removing 136 Air microfinishing film 202 English 9 removing from keyboard 154 dehumidifying 85 409 89 escapement of jack 76 repairing 240 humidifying 86 Fandrich 68 repetition, speed of 77 Air conditioner 86, 328 frame stability in verticals, Schwander 77 Albert Steinway 13, 76 A inspecting 191 single-escapement 4 Alcohol 144, 145, 147, 155, 156, 158, Abel 66, 71, 72, 340, 383 geometry 273, 303 spread 149, 280, 282, 287, 315 161, 179, 182, 191, 213, 217, 221, hammers 72, 384 geometry troubleshooter 304 tape-check 11 237, 238, 264, 265, 337, 338, 352, Naturals 71 grand, inserting into the piano troubleshooters 304 353, 356, 437, 439, 449, 478 Abrasive cord 338 137 Tubular Metallic Frame 66, 68 as sizing agent 215, 491 Abrasives, in buffing compounds grand, rebuilding 373 vertical 68 as solvent for shellac 480 364 grand, regulating 166 vertical, development of 15 as suspension for blue chalk 449 ABS grand, removing 136 vertical, Double Repetition 77 as suspension for chalk 240, 364, Carbon 17, 66 grand, removing from keyboard vertical, -

1785-1998 September 1998

THE EVOLUTION OF THE BROADWOOD GRAND PIANO 1785-1998 by Alastair Laurence DPhil. University of York Department of Music September 1998 Broadwood Grand Piano of 1801 (Finchcocks Collection, Goudhurst, Kent) Abstract: The Evolution of the Broadwood Grand Piano, 1785-1998 This dissertation describes the way in which one company's product - the grand piano - evolved over a period of two hundred and thirteen years. The account begins by tracing the origins of the English grand, then proceeds with a description of the earliest surviving models by Broadwood, dating from the late eighteenth century. Next follows an examination of John Broadwood and Sons' piano production methods in London during the early nineteenth century, and the transition from small-scale workshop to large factory is noted. The dissertation then proceeds to record in detail the many small changes to grand design which took place as the nineteenth century progressed, ranging from the extension of the keyboard compass, to the introduction of novel technical features such as the famous Broadwood barless steel frame. The dissertation concludes by charting the survival of the Broadwood grand piano since 1914, and records the numerous difficulties which have faced the long-established company during the present century. The unique feature of this dissertation is the way in which much of the information it contains has been collected as a result of the writer's own practical involvement in piano making, tuning and restoring over a period of thirty years; he has had the opportunity to examine many different kinds of Broadwood grand from a variety of historical periods. -

8002-Cedille-On-The-Move-Booklet.Pdf

INTRODUCTION 1 JOHN ADAMS (b. 1946) I. Relaxed Groove from Road Movies (4:37) Cedille Records is devoted to promoting the finest musicians in and from Chicago by re- Jennifer Koh, violin leasing their efforts on high quality recordings. Our recording ideas come from the artists themselves, which is why we have such a widely varied catalog of innovatively programmed Reiko Uchida, piano recordings. From In 2004, Cedille released a sampler CD of calming compositions titled Serenely Cedille (Ce- String Poetic — dille Records CDR 8001). Now, five years later, we present a disc of high-energy selections st from our catalog, ideal for keeping you “on the move,” whether walking, running, biking, American Works: A 21 Century Perspective driving, exercising, or just enjoying the music’s rhythmic drive. The tracks run the gamut CDR 90000 103 from a Vivaldi flute concerto, to symphonic works by late-Classical era composers from Bohemia (Krommer and Voříšek), to (later) 19th century concertos and chamber works, to seven selections by contemporary or very recent composers. All feature propulsive rhyth- mic energy designed to keep the music (and you) moving forward. This is the piece that inspired the idea for this sampler CD. About it, the iconic American I hope you enjoy this disc, and that it inspires you to want to learn more about and hear composer writes, “Road Movies is travel music, music that is comfortably settled in a pulse more from the wonderful Chicago artists represented on this CD. Toward that end, the track groove and passes through harmonic and textural regions as one would pass through a listing in this booklet includes a short statement about each selection and its respective landscape on a car trip.” Although titled, “Relaxed Grove,” the opening movement conveys disc. -

ARIANE GRAY HUBERT Concert Pianist, Singer & Composer Www

ARIANE GRAY HUBERT Concert Pianist, Singer & Composer www.arianegrayhubert.com A concert pianist, singer and composer, Ariane Gray Hubert is a much acclaimed and innovative artist in several fields. Over the years, she has delighted audiences and critics all over the world with her performances, be it a piano solo recital, a piano-vocal world music program or with various music ensembles. In her orchestral works, she blends both eastern and western music traditions in a unique manner—an absolutely visionary approach. Born in Paris with a French-American double nationality, the artist started her musical journey at the age of four. She was largely influenced by her American mother, Tamara Gray, and her great- aunt, who received her training from Alfred Cortot in Switzerland. The classical training Ariane Gray Hubert received is fascinating and ranged from the renowned Russian, Austrian and French piano traditions to the rich, oral music of the east. The distinctive characteristics of this French-American artist combine playing and singing together in expressive scales, her unique improvisation, powerful rhythmical ideas and inspiration from ancient musical traditions. In the west, the artist performs for major international festivals as well as for many productions in opera and dance. She played for Radio France, Musée d’Orsay, Opera Bastille & Garnier, the Vatican, the UNESCO, the European Delegation in India on the occasion of the 50 years of the EU Treaty, the French Alliances abroad (Austria, Germany, Italy, Baltic countries, India) and for various South American festivals. In 2010, in collaboration with various festivals abroad, she played “La Note Bleue” at the closing ceremony of the Festival “Bonjour India” to commemorate the bicentenary birth anniversary of F. -

Pedal in Liszt's Piano Music!

! Abstract! The purpose of this study is to discuss the problems that occur when some of Franz Liszt’s original pedal markings are realized on the modern piano. Both the construction and sound of the piano have developed since Liszt’s time. Some of Liszt’s curious long pedal indications produce an interesting sound effect on instruments built in his time. When these pedal markings are realized on modern pianos the sound is not as clear as on a Liszt-time piano and in some cases it is difficult to recognize all the tones in a passage that includes these pedal markings. The precondition of this study is the respectful following of the pedal indications as scored by the composer. Therefore, the study tries to find means of interpretation (excluding the more frequent change of the pedal), which would help to achieve a clearer sound with the !effects of the long pedal on a modern piano.! This study considers the factors that create the difference between the sound quality of Liszt-time and modern instruments. Single tones in different registers have been recorded on both pianos for that purpose. The sound signals from the two pianos have been presented in graphic form and an attempt has been made to pinpoint the dissimilarities. In addition, some examples of the long pedal desired by Liszt have been recorded and the sound signals of these examples have been analyzed. The study also deals with certain aspects of the impact of texture and register on the clarity of sound in the case of the long pedal. -

Ellen Fullman

A Compositional Approach Derived from Material and Ephemeral Elements Ellen Fullman My primary artistic activity has been focused coffee cans with large metal mix- around my installation the Long String Instrument, in which ing bowls filled with water and rosin-coated fingers brush across dozens of metallic strings, rubbed the wires with my hands, ABSTRACT producing a chorus of minimal, organ-like overtones, which tipping the bowl to modulate the The author discusses her has been compared to the experience of standing inside an sound. I wanted to be able to tune experiences in conceiving, enormous grand piano [1]. the wire, but changing the tension designing and working with did nothing. I knew I needed help the Long String Instrument, from an engineer. At the time I was an ongoing hybrid of installa- BACKGROUND tion and instrument integrat- listening with great interest to Pau- ing acoustics, engineering In 1979, during my senior year studying sculpture at the Kan- line Oliveros’s album Accordion and and composition. sas City Art Institute, I became interested in working with Voice. I could imagine making mu- sound in a concrete way using tape-recording techniques. This sic with this kind of timbre, playing work functioned as soundtracks for my performance art. I also created a metal skirt sound sculpture, a costume that I wore in which guitar strings attached to the toes and heels of my Fig. 1. Metal Skirt Sound Sculpture, 1980. (© Ellen Fullman. Photo © Ann Marsden.) platform shoes and to the edges of the “skirt” automatically produced rising and falling glissandi as they were stretched and released as I walked (Fig. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

JORDAN This Publication Has Been Produced with the Financial Assistance of the European Union Under the ENI CBC Mediterranean

ATTRACTIONS, INVENTORY AND MAPPING FOR ADVENTURE TOURISM JORDAN This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Official Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Services and Navigation of Barcelona and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Programme management structures. The European Union is made up of 28 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintaining cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. The European Union is committed to sharing its achievements and its values with countries and peoples beyond its borders. The 2014-2020 ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme is a multilateral Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) initiative funded by the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI). The Programme objective is to foster fair, equitable and sustainable economic, social and territorial development, which may advance cross-border integration and valorise participating countries’ territories and values. The following 13 countries participate in the Programme: Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta, Palestine, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia. The Managing Authority (JMA) is the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (Italy). Official Programme languages are Arabic, English and French. For more information, please visit: www.enicbcmed.eu MEDUSA project has a budget of 3.3 million euros, being 2.9 million euros the European Union contribution (90%). -

Mtv and Transatlantic Cold War Music Videos

102 MTV AND TRANSATLANTIC COLD WAR MUSIC VIDEOS WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH INTRODUCTION In 1986 Music Television (MTV) premiered “Peace Sells”, the latest video from American metal band Megadeth. In many ways, “Peace Sells” was a standard pro- motional video, full of lip-synching and head-banging. Yet the “Peace Sells” video had political overtones. It featured footage of protestors and police in riot gear; at one point, the camera draws back to reveal a teenager watching “Peace Sells” on MTV. His father enters the room, grabs the remote and exclaims “What is this garbage you’re watching? I want to watch the news.” He changes the channel to footage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the 1986 nuclear arms control summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. The son, perturbed, turns to his father, replies “this is the news,” and lips the channel back. Megadeth’s song accelerates, and the video re- turns to riot footage. The song ends by repeatedly asking, “Peace sells, but who’s buying?” It was a prescient question during a 1980s in which Cold War militarism and the nuclear arms race escalated to dangerous new highs.1 In the 1980s, MTV elevated music videos to a new cultural prominence. Of course, most music videos were not political.2 Yet, as “Peace Sells” suggests, dur- ing the 1980s—the decade of Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and a robust nuclear arms race—music videos had the potential to relect political concerns. MTV’s founders, however, were so culturally conserva- tive that many were initially wary of playing African American artists; addition- ally, record labels were hesitant to put their top artists onto this new, risky chan- 1 American President Ronald Reagan had increased peace-time deicit defense spending substantially. -

Andrew Nolan Viennese

Restoration report South German or Austrian Tafelklavier c. 1830-40 Andrew Nolan, Broadbeach, Queensland. copyright 2011 Description This instrument is a 6 1/2 octave (CC-g4) square piano of moderate size standing on 4 reeded conical legs with casters, veneered in bookmatched figured walnut in Biedermeier furniture style with a single line of inlaid stringing at the bottom of the sides and a border around the top of the lid. This was originally stained red to resemble mahogany and the original finish appearance is visible under the front lid flap. The interior is veneered in bookmatched figured maple with a line of dark stringing. It has a wrought iron string plate on the right which is lacquered black on a gold base with droplet like pattern similar to in concept to the string plates of Broadwood c 1828-30. The pinblock and yoke are at the front of the instrument over the keyboard as in a grand style piano and the bass strings run from the front left corner to the right rear corner. The stringing is bichord except for the extreme bass CC- C where there are single overwound strings, and the top 1 1/2 octaves of the treble where there is trichord stringing. The top section of the nut for the trichords is made of an iron bar with brass hitch pins inserted at the top, this was screwed and glued to the leading edge of the pinblock. There is a music rack of walnut which fits into holes in the yoke. The back of this rack is hinged in the middle and at the bottom. -

Piano Manufacturing an Art and a Craft

Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Gesa Lücker (Concert pianist and professor of piano, University for Music and Drama, Hannover) Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Since time immemorial, music has accompanied mankind. The earliest instrumentological finds date back 50,000 years. The first known musical instrument with fibers under ten sion serving as strings and a resonator is the stick zither. From this small beginning, a vast array of plucked and struck stringed instruments evolved, eventually resulting in the first stringed keyboard instruments. With the invention of the hammer harpsichord (gravi cembalo col piano e forte, “harpsichord with piano and forte”, i.e. with the capability of dynamic modulation) in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, the pianoforte was born, which over the following centuries evolved into the most versitile and widely disseminated musical instrument of all time. This was possible only in the context of the high level of devel- opment of artistry and craftsmanship worldwide, particu- larly in the German-speaking part of Europe. Since 1885, the Schimmel family has belonged to a circle of German manufacturers preserving the traditional art and craft of piano building, advancing it to ever greater perfection. Today Schimmel ranks first among the resident German piano manufacturers still owned and operated by Contents the original founding family, now in its fourth generation. Schimmel pianos enjoy an excellent reputation worldwide. 09 The Fascination of the Piano This booklet, now in its completely revised and 15 The Evolution of the Piano up dated eighth edition, was first published in 1985 on The Origin of Music and Stringed Instruments the occa sion of the centennial of Wilhelm Schimmel, 18 Early Stringed Instruments – Plucked Wood Pianofortefa brik GmbH. -

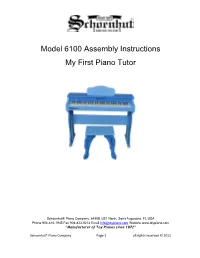

Model 6100 Assembly Instructions My First Piano Tutor

Model 6100 Assembly Instructions My First Piano Tutor Schoenhut® Piano Company, 6480B US1 North, Saint Augustine, FL USA Phone 904-810-1945 Fax 904-823-9213 Email [email protected] Website www.toypiano.com “Manufacturer of Toy Pianos since 1872” Schoenhut® Piano Company Page 1 all rights reserved © 2011 Printed in China WARNING! This product must be assembled by an adult prior to play. Unassembled parts may have sharp edges which could cause injury. The piano and bench are designed for use by a child. Inspect the hardware periodically for tightness and integrity, tightening or replacing any loose parts. Parts Piano body Bench seat Piano Crosspiece leg support 7” Bench Legs (two) Piano Legs (two) 6.25” Bench Legs (two) Music Stand Long Screws (ten) Song book and color strip Short Screws (four) Learning System book Barrel Nuts (fourteen) Microphone (one) Pedal (one) Power Adapter (one) Assembly Alert: Hardware is located inside the Styrofoam packing material Step1: Insert barrel nuts into the top portion of the (2) sets of piano legs. Use (2) long screws to attach the piano leg to the piano body. Repeat this for other side. Step 2: Insert (4) barrel nuts into the crosspiece. Use (4) long screws to attach the piece onto the piano legs. Step 3: To put the bench together, you will insert barrel nuts into the holes of each bench leg. Place (1) 7 inch bench leg and (1) 6.25 inch bench leg together so that they make “V” shape. Attach these together using (2) long screws. Do the same for the remaining (2) bench legs.