Leiden Gallery Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ART 486 / 586 Baroque Art Fall 2018

ART 486 / 586 Baroque Art fall 2018 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR after class until noon, TR 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 9:30 – 10:45 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex Building. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 281, 282 or the equivalent in history. Program Learning Outcomes (for art history majors, of which there are none in the class) 1. Foundation Skills 2. Interpretative Skills 3. Research Skills Undergraduate students will conduct art historical research involving logical and insightful analysis of secondary literature. Category: Embedded course assignment (research paper) Text: Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for example, on Aug. 22 there were 3 used copies of the 1st ed in acceptable condition for less than $7.19 or 7.23 and one good for $11.98 on bookfinder.com. I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one at exam times. Work schedule: A. 2 non-comprehensive quizzes identifying works and terms, collectively worth 20% if higher than other work, 10% if lower. The extra 5% will count toward other work with the highest grade. -

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

ARTS 5306 Crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art History Fall 2020

ARTS 5306 crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art HIstory fall 2020 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR 11:00 – 12:00, 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 2:00 – 3:15 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex and remotely. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 1303 and 1304 (Art History I and II) or the equivalent in history. Text: Not required. The artists and most artworks come from Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one. Objectives: .1a Broaden your interest in Baroque art in Europe by examining artworks by artists we studied in Art History II and artists perhaps new to you. .1b Understand the social, political and religious context of the art. .2 Identify major and typical works by leading artists, title and country of artist’s origin and terms (id quizzes). .3 Short essays on artists & works of art (midterm and end-term essay exams) .4 Evidence, analysis and argument: read an article and discuss the author’s thesis, main points and evidence with a small group of classmates. -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

Rembrandt: the Denial of Peter

http://www.amatterofmind.us/ PIERRE BEAUDRY’S GALACTIC PARKING LOT REMBRANDT: THE DENIAL OF PETER How an artistic composition reveals the essence of an axiomatic moment of truth By Pierre Beaudry, 9/23/16 Figure 1 Rembrandt (1606-1669), The Denial of Peter, (1660) Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Page 1 of 14 http://www.amatterofmind.us/ PIERRE BEAUDRY’S GALACTIC PARKING LOT INTRODUCTION: A PRAYER ON CANVAS All four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John have reported on the prediction that Jesus made during the Last Supper, stating that Peter would disown him three times before the night was over, and all four mentioned the event of that denial in one form or another. If ever there was a religious subject that was made popular for painters in the Netherlands during the first half of the seventeenth century, it was the denial of Peter. More than twenty European artists of that period, most of them were Dutch, chose to depict the famous biblical scene, but none of them touched on the subject in the profound axiomatic manner that Rembrandt did. Rembrandt chose to go against the public opinion view of Peter’s denial and addressed the fundamental issue of the axiomatic change that takes place in the mind of an individual at the moment when he is confronted with the truth of having to risk his own life for the benefit of another. This report has three sections: 1. THE STORY OF THE NIGHT WHEN PETER’S LIFE WAS CHANGED 2. THE TURBULENT SENSUAL NOISE BEHIND THE DIFFERENT POPULAR PAINTINGS OF PETER’S DENIAL 3. -

“The Concert” Oil on Canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ Ins., 105.5 by 133.5 Cms

Dirck Van Baburen (Wijk bij Duurstede, near Utrecht 1594/5 - Utrecht 1624) “The Concert” Oil on canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ ins., 105.5 by 133.5 cms. Dirck van Baburen was the youngest member of the so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti, a group of artists all hailing from the city of Utrecht or its environs, who were inspired by the work of the famed Italian painter, Caravaggio (1571-1610). Around 1607, Van Baburen entered the studio of Paulus Moreelse (1571- 1638), an important Utrecht painter who primarily specialized in portraiture. In this studio the fledgling artist probably received his first, albeit indirect, exposure to elements of Caravaggio’s style which were already trickling north during the first decade of the new century. After a four-year apprenticeship with Moreelse, Van Baburen departed for Italy shortly after 1611; he would remain there, headquartered in Rome, until roughly the summer of 1620. Caravaggio was already deceased by the time Van Baburen arrived in the eternal city. Nevertheless, his Italian period work attests to his familiarity with the celebrated master’s art. Moreover, Van Baburen was likely friendly with one of Caravaggio’s most influential devotees, the enigmatic Lombard painter Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622). Manfredi and Van Baburen were recorded in 1619 as living in the same parish in Rome. Manfredi’s interpretations of Caravaggio’s are profoundly affected Van Baburen as well as other members of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Van Baburen’s output during his Italian sojourn is comprised almost entirely of religious paintings, some of which were executed for Rome’s most prominent churches. -

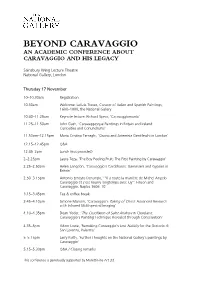

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia Cár - Pozri Jurodiví/Blázni V Kristu; Rusko

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia cár - pozri jurodiví/blázni v Kristu; Rusko Georges Becker: Korunovácia cára Alexandra III. a cisárovnej Márie Fjodorovny Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 1 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia N. Nevrev: Roman Veľký prijíma veľvyslanca pápeža Innocenta III (1875) Cár kolokol - Expres: zvon z počiatku 17.st. odliaty na príkaz cára Borisa Godunova (1552-1605); mal 36 ton; bol zavesený v štvormetrovej výške a rozhojdávalo ho 12 ľudí; počas jedného z požiarov spadol a rozbil sa; roku 1654 z jeho ostatkov odlial ruský majster Danilo Danilov ešte väčší zvon; o rok neskoršie zvon praskol úderom srdca; ďalší nasledovník Cára kolokola bol odliaty v Kremli; 24 rokov videl na provizórnej konštrukcii; napokon sa našiel majster, ktorému trvalo deväť mesiacov, kým ho zdvihol na Uspenský chrám; tam zotrval do požiaru roku 1701, keď spadol a rozbil sa; dnešný Cár kolokol bol formovaný v roku 1734, ale odliaty až o rok neskoršie; plnenie formy kovom trvalo hodinu a štvrť a tavba trvala 36 hodín; keď roku 1737 vypukol v Moskve požiar, praskol zvon pri nerovnomernom ochladzovaní studenou vodou; trhliny sa rozšírili po mnohých miestach a jedna časť sa dokonca oddelila; iba tento úlomok váži 11,5 tony; celý zvon váži viac ako 200 ton a má výšku 6m 14cm; priemer v najširšej časti je 6,6m; v jeho materiáli sa okrem klasickej zvonoviny našli aj podiely zlata a striebra; viac ako 100 rokov ostal zvon v jame, v ktorej ho odliali; pred rokom 2000 poverili monumentalistu Zuraba Cereteliho odliatím nového Cára kolokola, ktorý mal odbiť vstup do nového milénia; myšlienka však nebola doteraz zrealizovaná Caracallove kúpele - pozri Rím http://referaty.atlas.sk/vseobecne-humanitne/kultura-a-umenie/48731/caracallove-kupele Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 2 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia G. -

Technical Art History Colloquium

TECHNICAL ART HISTORY COLLOQUIUM ‘The Calling of St. Matthew’ (1621) by Hendrick ter Brugghen. Centraal Museum, Utrecht The Technical Art History Colloquium is organised by Sven Dupré (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam, PI ERC ARTECHNE), Arjan de Koomen (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History) and Abbie Vandivere (Paintings conservator, Mauritshuis, The Hague & Vice-Program Director MA Technical Art History). Monthly meetings take place on Thursdays, alternately in Utrecht and Amsterdam. The fifth edition of the Technical Art History Colloquium will be held at the Centraal Museum Utrecht, in connection with the upcoming exhibition Caravaggio, Utrecht and Europe. Liesbeth M. Helmus (Curator of old masters, Centraal Museum Utrecht) will present preliminary results of technical research on paintings by Dirck van Baburen and Hendrick ter Brugghen. Marco Cardinali (Technical art historian at Emmebi Diagnostica Artistica, Rome and visiting professor at the Stockholm University and UNAM-Mexico City) will present — as co-editor and curator of the scientific research — the recently published Caravaggio. Works in Rome. Technique and Style (2016). The result of an ambitious project launched in 2009 and funded by the National Committee for the Celebrations of the Fourth Centenary of the Death of Caravaggio, this book sheds light on Caravaggio’s pictorial methods through technical research on twenty- two unquestionably original works in Rome. Date: September 22, 2016 Time: 14:00 – 16:00 (presentations) — 16:00 – 17:00 (possibility to visit the museum) Location: Centraal Museum, Agnietenstraat 1, Utrecht — Aula Admission free Caravaggio’s Painting Technique and the Art Critique. A Technical Art History Marco Cardinali The recently published book Caravaggio. -

The Utrecht Caravaggisti the Painter of This Picture, Jan Van Bijlert, Was Born in Utrecht in the Netherlands, a City Today Stil

The Utrecht Caravaggisti The painter of this picture, Jan van Bijlert, was born in Utrecht in the Netherlands, a city today still known for its medieval centre and home to several prominent art museums. In his beginnings, Jan van Bijlert became a student of Dutch painter Abraham Bloemaert. He later spent some time travelling in France as well as spending the early 1620s in Rome, where he was influenced by the Italian painter Caravaggio. This brings us on to the Caravaggisti, stylistic followers of this late 16th-century Italian Baroque painter. Caravaggio’s influence on the new Baroque style that eventually emerged from Mannerism was profound. Jan van Bijlert had embraced his style totally before returning home to Utrecht as a confirmed Caravaggist in roughly 1645. Caravaggio tended to differ from the rest of his contemporaries, going about his life and career without establishing as much as a studio, nor did he try to set out his underlying philosophical approach to art, leaving art historians to deduce what information they could from his surviving works alone. Another factor which sets him apart from his contemporaries is the fact that he was renowned during his lifetime although forgotten almost immediately after his death. Many of his works were released into the hands of his followers, the Caravaggisti. His relevance and major role in developing Western art was noticed at quite a later time when rediscovered and was ‘placed’ in the European tradition by Roberto Longhi. His importance was quoted as such, "Ribera, Vermeer, La Tour and Rembrandt could never have existed without him. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St.