Close Analysis of a Single Work of Art >Examination of the Work's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

“The Concert” Oil on Canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ Ins., 105.5 by 133.5 Cms

Dirck Van Baburen (Wijk bij Duurstede, near Utrecht 1594/5 - Utrecht 1624) “The Concert” Oil on canvas 41 ½ by 52 ½ ins., 105.5 by 133.5 cms. Dirck van Baburen was the youngest member of the so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti, a group of artists all hailing from the city of Utrecht or its environs, who were inspired by the work of the famed Italian painter, Caravaggio (1571-1610). Around 1607, Van Baburen entered the studio of Paulus Moreelse (1571- 1638), an important Utrecht painter who primarily specialized in portraiture. In this studio the fledgling artist probably received his first, albeit indirect, exposure to elements of Caravaggio’s style which were already trickling north during the first decade of the new century. After a four-year apprenticeship with Moreelse, Van Baburen departed for Italy shortly after 1611; he would remain there, headquartered in Rome, until roughly the summer of 1620. Caravaggio was already deceased by the time Van Baburen arrived in the eternal city. Nevertheless, his Italian period work attests to his familiarity with the celebrated master’s art. Moreover, Van Baburen was likely friendly with one of Caravaggio’s most influential devotees, the enigmatic Lombard painter Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582-1622). Manfredi and Van Baburen were recorded in 1619 as living in the same parish in Rome. Manfredi’s interpretations of Caravaggio’s are profoundly affected Van Baburen as well as other members of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Van Baburen’s output during his Italian sojourn is comprised almost entirely of religious paintings, some of which were executed for Rome’s most prominent churches. -

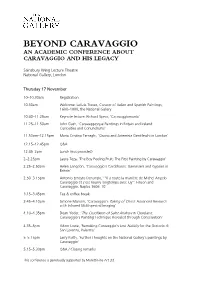

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

Technical Art History Colloquium

TECHNICAL ART HISTORY COLLOQUIUM ‘The Calling of St. Matthew’ (1621) by Hendrick ter Brugghen. Centraal Museum, Utrecht The Technical Art History Colloquium is organised by Sven Dupré (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam, PI ERC ARTECHNE), Arjan de Koomen (University of Amsterdam, Coordinator MA Technical Art History) and Abbie Vandivere (Paintings conservator, Mauritshuis, The Hague & Vice-Program Director MA Technical Art History). Monthly meetings take place on Thursdays, alternately in Utrecht and Amsterdam. The fifth edition of the Technical Art History Colloquium will be held at the Centraal Museum Utrecht, in connection with the upcoming exhibition Caravaggio, Utrecht and Europe. Liesbeth M. Helmus (Curator of old masters, Centraal Museum Utrecht) will present preliminary results of technical research on paintings by Dirck van Baburen and Hendrick ter Brugghen. Marco Cardinali (Technical art historian at Emmebi Diagnostica Artistica, Rome and visiting professor at the Stockholm University and UNAM-Mexico City) will present — as co-editor and curator of the scientific research — the recently published Caravaggio. Works in Rome. Technique and Style (2016). The result of an ambitious project launched in 2009 and funded by the National Committee for the Celebrations of the Fourth Centenary of the Death of Caravaggio, this book sheds light on Caravaggio’s pictorial methods through technical research on twenty- two unquestionably original works in Rome. Date: September 22, 2016 Time: 14:00 – 16:00 (presentations) — 16:00 – 17:00 (possibility to visit the museum) Location: Centraal Museum, Agnietenstraat 1, Utrecht — Aula Admission free Caravaggio’s Painting Technique and the Art Critique. A Technical Art History Marco Cardinali The recently published book Caravaggio. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St. -

CLASSROOM RESOURCE SHEET Allen Memorial Art Museum

CLASSROOM RESOURCE SHEET Allen Memorial Art Museum wrap and softly draping robes cleans his wounds and prepares his body for burial, while another woman works to untie him. The man’s body is thin and haggard, tinged a grey-green color, implying his suffering and near-death state. Ter Brugghen has paid particular attention to the anatomy of Saint Sebastian, using heavy shadows to emphasize details like his ribs, musculature, and gaunt cheeks. He slumps over with clear weight, yet Saint Irene seems to keep him upright effortlessly. Her delicate touch holds the dead saint, and gently begins to remove an arrow from his side. The artist also visually connects Sebastian and Irene, by unifying their skin tone. Irene’s empathy seems so intense that she adopts the pallor of Sebastian. This unifi ed skin tone also serves to focus the narrative—the central fi gures in the story stand out, while the remaining fi gure fades into the background. FUNCTION/FORM & STYLE The arrangement of the fi gures is the central theme of the composition. The work is united by the strong diagonal movement from the man’s outstretched arm down to his head, past his half- closed eyes, to his lower left foot. Saint Sebastian Tended By Irene, 1625 This line is paralleled in the diagonal of the two women’s heads above Hendrick ter Brugghen (Dutch, 1588-1629) his own. The viewer’s low, close-up Oil on canvas | 58 15/16 x 47 ¼ in. (149.5 x 120 cm) perspective contributes to the emotion and immediacy. -

National Gallery of Art Collection Exhibitions Education Conservation Research Calendar Visit Support Shop

National Gallery of Art Collection Exhibitions Education Conservation Research Calendar Visit Support Shop National Gallery of Art :: Press Office :: null :: Gerrit van Honthorst Search NGA.gov Release Date: November 22, 2013 National Gallery of Art Announces Major Acquisition of Gerrit van Honthorst's AVAILABLE PRESS IMAGES The Concert, 1623 Order Press Images To order publicity images: Click on the link above and designate your desired images using the checkbox below each thumbnail. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned. PRESS KIT Press Release ONLINE RESOURCES PRESS CONTACTS Anabeth Guthrie (202) 842-6804 Gerrit van Honthorst, Dutch, 1592 – 1656 [email protected] The Concert, 1623 Chief Press Officer oil on canvas. unframed: 123 × 206 cm (48 7/16 × 81 1/8 in.) Deborah Ziska National Gallery of Art, Washington. Patrons’ Permanent Fund and Florian Carr Fund [email protected] 2013.38.1 (202) 842-6353 Washington, DC—The National Gallery of Art announces the acquisition of a Dutch masterpiece by Gerrit van Honthorst (1592–1656), considered one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age. The Concert, dated 1623, is an important and historic painting that has not been seen publicly since 1795. The acquisition is made possible by the Patrons' Permanent Fund and Florian Carr Fund. Honthorst was one of the Utrecht "Caravaggisti," and like many other European artists of his generation, he traveled to Rome, where he was inspired by the radical stylistic and thematic ideas of Italian baroque painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. -

Wayne E. Franits Distinguished Professor of Art History Department of Art & Music Histories Syracuse University (315) 443-5038 [email protected] December 2020

Wayne E. Franits Distinguished Professor of Art History Department of Art & Music Histories Syracuse University (315) 443-5038 [email protected] December 2020 PUBLICATIONS: Books, Authored: Godefridus Schalcken; A Dutch Painter in Late Seventeenth-Century London, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, 2018, 288 pp., 86 color illus. - reviewed in The Burlington Magazine Vermeer, London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2015, 352 pp., 124 color illus. - reviewed in The Burlington Magazine The Paintings of Dirck van Baburen ca. 1592/93-1624: Catalogue Raisonné, Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2013, xx, 388 pp., 114 black-and-white illus., 15 color illus. - reviewed in Apollo; De Zeventiende Eeuw; The Burlington Magazine; HNA Review of Books The Paintings of Hendrick ter Brugghen 1588-1629: Catalogue Raisonné [co- author with Leonard J. Slatkes], Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2007, xix + 468 pp., 204 black-and-white illus., 17 color illus. -reviewed in Choice; The Burlington Magazine; Kunstchronik, Simiolus; The Art Newspaper; De Zeventiende Eeuw; La Tribune de l’Art; HNA Review of Books Pieter de Hooch: A Woman Preparing Bread and Butter for a Boy (Getty Museum Studies of Art), Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006, 86 pp., 24 black- and-white illus., 34 color illus. Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution, London/ New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, viii + 328 pp., 166 black-and- white illus., 70 color illus. -Paperback edition, 2008. -reviewed in N.R.C. Handelsblad; Publisher=s Weekly; Choice (included in Choice’s Outstanding Academic Titles List, January 2006); CAAElectronic Reviews; London Review of Books; Sixteenth-Century Journal; Seventeenth- Century News; De Zeventiende Eeuw Paragons of Virtue; Women and Domesticity in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art, Cambridge/ New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993, xx + 271 pp., 172 black-and-white illus. -

A New Drawing by Hendrick Ter Brugghen

A new drawing by Hendrick ter Brugghen Leonard J. Slatkes The recent appearance of a new drawing by the Utrecht caravaggesque painter Hendrick ter Brugghen (fig. 1), part of the Badezou gift, musee de Rouen,! a study for the 1628 da ted Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, De- mocritus2 (fig. 2), and the surprising results of an X-ray (fig. 3) of another Ter Brugghen picture, the c. 1623 Scene 01 Mercenary Love: Unequal Lovers (fig. 4), now in the Shearson Lehman Brothers collection, New Y ork, both contribute to our understanding of the role drawings played in the common workshop shared by Ter Brugghen and Dirck van Baburen between about 1621 and the latter's death early in 1624, as well as later when Ter Brugghen worked independently. The new Rouen drawing is executed in black chalk with some heightening in white chalk on grey paper,3200 x 300 mm., and thus is very similar in technique to the two already known Ter Brugghen drawings, although it does lack the wash found in the other sheets and thus appears somewhat less finished. Interestingly enough, this new Ter Brugghen drawing has a traceable provenance, even though - or perhaps, because - it had always been attributed to Gerrit van Honthorst. Indeed, both of the other Ter Brugghen drawings were also originally attributed to Honthorst. Thus the Rouen drawing appeared in the 1900 Defer-Dumesnil sale,4 and again in the 1920 Y. Beurdeley sale. 5 Furthermore, in 1879 the sheet had been exhibited at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris, no. 329, once again as Hont horst.6 To this already known history it is now possible to add that the Same work is almost certainly the Democritus drawing, described as being executed in black chalk with white highlights, in the auction van der Dussen, Amsterdam, Oct. -

Leiden Gallery Site

© 2017 Leiden Gallery Allegory of Faith Page 2 of 9 Allegory of Faith ca. 1626 Hendrick ter Brugghen oil on canvas (The Hague 1588 – 1629 Utrecht) 72.3 x 56.3 cm signed and dated in the light paint along the center of the left edge: “HTBrügghen 162(?)” (“HTB” in ligature) HBr-100 Currently on view at Centraal Museum How To Cite Ilona van Tuinen, "Allegory of Faith", (HBr-100), in The Leiden Collection Catalogue, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Ed., New York, 2017 http://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/ This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. In the corner of a humble room sits a young woman who, with a smile spread across her slightly parted lips, gazes upward, her dark eyes fixated on a higher realm. Hendrick ter Brugghen framed the woman’s face with a high-necked vest and a cream-colored headscarf that falls in thick creases over her shoulders. A heavy blue mantle wrapped over her arms covers a red undergarment, the left sleeve of which is just visible. The large cross she holds on her lap, its left arm only partially seen behind her left shoulder, Fig 1. Hendrick Ter Brugghen, indicates the spiritual essence of her rapture.[1] Musical Trio [The Concert], ca. 1626, oil on canvas, 99.1 x Unifying the composition and establishing its reflective mood is the light 116.8 cm, National Gallery, London, Bought with shining from the simple candle the woman holds in her left hand.