Capturing Cotton's Metropolis: the Struggle For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great River Road Tennessee

Great River Road Tennessee Corridor Management Plan Corridor Management Plan Recognitions Mayor AC Wharton Shelby County Byway Consultant Mayor Jeff Huffman Tipton County David L. Dahlquist Mayor Rod Schuh Lauderdale County Governor Phil Bredesen President Mayor Richard Hill Dyer County State of Tennessee David L. Dahlquist Associates, L.L.C. Mayor Macie Roberson Lake County State Capitol 5204 Shriver Avenue Mayor Benny McGuire Obion County Nashville, TN 37243 Des Moines, IA 50312 Commissioner Susan Whitaker Pickering Firm, Inc Department of Tourist Development Byway Planning Team Architecture – Engineering – Planning – Surveying Wm. Snodgrass/Tennessee Tower 312 8th Avenue North, 25th Floor Bob Pitts, PE Nashville, TN 37243 Mississippi River Corridor – Tennessee, Inc. Principal Owner Board of Directors Director, Civil Engineering Services Ms. Marty Marbry 6775 Lenox Center Court – Suite 300 West Tennessee – Tourist Development Memphis, TN 38115 Regional Marketing & Public Relations John Sheahan Chairman/CEO John Threadgill Secretary Historical Consultant Commissioner Gerald Nicely Dr. Carroll Van West Tennessee Department of Transportation Jim Bondurant Chair – Obion - Task Force Committe Director 505 Deaderick St. Rosemary Bridges Chair – Tipton - Task Force Committee Center for Historic Preservation James K. Polk Bldg. – 7th Floor Peter Brown Chair – Dyer - Task Force Committee Middle Tennessee State University Nashville, TN 37243 Laura Holder Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area P.O. Box 80 – MTSU Pamela Marshall Public Affairs -

Vol 26 No3 1979.Pdf

I Published by THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY Memphis, Tennessee ..- .. I Mrs. Gene F. Davis, Editor VOLUME 26 FALL, 1979 NUMBER 3 - CONTENTS - OVER THE EDITOR'S DESK •••••••••. ". 101 ) NEWS AND NOTES FROM OTHER PUBLICATIONS 102 BOOK REVIEWS •••• 104 FROM THE MAIL BOX ••• 110 JEFFERSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, INDEX TO 1840 CENSUS 114 JEFFERSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, REVOLUTIONARY & MILITARY PENSIONERS, 1840 • 121 WARREN COUNTY, TENNESSEE, DEED BOOK D- ABSTRACTS. 122 DAVIDSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, TAX LIST ••••••••• . 128 WASHINGTON COUNTY , TENNESSEE, WILLS - ABSTRACTS • 133 FAYETTE COUNTY, TENNESSEE, COURT MINUTES •••••••••••••• •• 138 QUERIES •• •• . .. .. • • 144 THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY / " P.O. Box 12124 Memphis, Tennessee 38112 OFFICERS AND STAFF FOR 1979 President Mr. S. Caya Phillips Vice President Mrs. Augusta Brough Recording Secretary Mrs. F. H. O'Neal CorresPondence Secretary Mrs. Wilma Sutton Cogdell Librarian Mrs. Vivian L. Briggs Assistant Librarian Mrs. John D. Tyus Surname Index Secretary Mrs. Curtis Craven Treasurer Mr. John Hollis Editor Mrs. Bettie Brandon Davis Associate Editor Mrs. Daniel E. West Director Mrs. Charles Roy Gilley Director Mrs. Charles Barham, Jr. LIBRARY STAFF EDITORIAL STAFF BUSINESS STAFF Mrs. F. H. O'Neal Miss Myrtle Shelton Mrs. Homer D. Turner, Jr. Mrs. Jane Hollis Mrs. Jane Hollis Mrs. Charles Roy Gilley Mrs. Mary Kay Loomis Mr. Herman L. Bogan Mrs. Robert Louis Cox Mrs. Robert Louis Cox Mrs. Hilda Burrow Mrs. Henry N. Crymes Miss Jessie Webb Mrs. Charles West Mr. Floyd Simpson, Jr. Mr. Thomas P. Hughes, Jr. "ANSEARCHIN'" NEWS is the official publication of THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY; published quarterly in March, June, September, and December; annual subscription $7.00. All subscriptions begin with the first issue of the year. -

FAMILY DOLLAR 2 RIPLEY, TN LEASE & LOCATION • 40-Year Operating History at This Location Showing Strong Commitment to the Market

™ 180 S WASHINGTON ST | RIPLEY, TN 38063 OFFERING MEMORANDUM LISTED BY JOHNNY NOVOKMET ASSOCIATE DIRECT +1 (310) 844-9363 MOBILE +1 (310) 344-9394 [email protected] TABLE OF LIC # 02109963 (CA) CONTENTS JOSH BISHOP VP & DIRECTOR 03 EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW DIRECT +1 (214) 692-2289 MOBILE +1 (315) 730-6228 EXECUTIVE 04 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW [email protected] LIC # 688810 (CA) OVERVIEW 06 AREA OVERVIEW BROKER OF RECORD KYLE MATTHEWS LIC # 263667 (TN) 10 TENANT OVERVIEW FAMILY DOLLAR 2 RIPLEY, TN LEASE & LOCATION • 40-year operating history at this location showing strong commitment to the market • The subject property was renovated in 2014 including a brand new roof, HVAC system, parking lot, exterior facelift and remodel of the inside • 8-years remaining on the roof warranty • Extremely attractive 8.65% return for an investor seeking a high yield on a stabilized investment • NNN Lease with the tenant responsible for taxes, insurance, and common area maintenance (including parking lot repairs up to $5,000 annually) • Corporately guarantee lease • 5-mile population exceeds 13,050 residents EXECUTIVE • Six, 5-year renewal options all of which include an attractive 10% rent increase • Located in the heart of downtown Ripley just 700 feet from the Courthouse, Police Department, OVERVIEW Chamber of Commerce, and Gas & Water Department • Ripley appeared on Newsmax magazine’s list of “Top 25 Most Uniquely American Cities and Towns,” a piece written by current CBS News travel editor Peter Greenberg TENANT • Family Dollar was acquired by -

Memphisbinder (Read-Only)

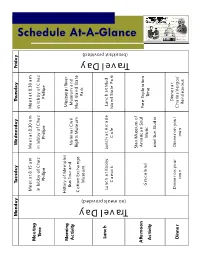

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Schedule At-A-Glance Meet at 8:15 am Meet at 8:30 am Meet at 8:30 am Meeting Time in lobby of Chez in lobby of Chez in lobby of Chez Phillipe Phillipe Phillipe Morning History of Memphis Mississippi River Bus Tour and Activity National Civil Museum and Rights Museum Mud Island State Cotton Exchange Museum Park Lunch Lunch at Kooky Lunch at Arcade Lunch at Mud Canuck Cafe Island State Park (no meals provided) (breakfast provided) Travel Day Travel Day Stax Museum of Afternoon American Soul Free Exploration Graceland Music Activity Time and Sun Studio Dinner at Dinner on your Dinner on your Dinner Charles Vergos’ own own Rendezvous Detailed Itinerary Monday, June 21, 2010: Travel Day—no planned activities Tuesday, June 22, 2010 8:15 am Meet in lobby of Chez Phillipe 8:30 am Memphis History Bus Tour 10:30 am Arrive at the Cotton Museum at the Memphis Cotton Exchange 10:45 am Tour of the Cotton Museum at the Memphis Cotton Exchange 11:45 pm Walk to the Kooky Canuck for lunch (97 S. Second Street, Memphis) 12:00 pm Lunch at the Kooky Canuck 1:20 pm Board bus and travel to Graceland 2:00 pm Tour and explore Graceland 4:30 pm Board bus and travel back to hotel. 5:00 pm Arrive at hotel. Dinner on your own. Wednesday, June 23, 2010 8:30 am Meet in lobby of Chez Phillipe 8:45 am Board bus and travel to National Civil Rights Museum 9:00 am Tour and explore National Civil Rights Museum Detailed Itinerary 11:00 am Lunch at the Arcade Café (540 S. -

From Nashville to Memphis April 11 - 17, 2016| 7 Days

American Classic Tours, Inc. presents MUSIC ROAD: From Nashville to Memphis April 11 - 17, 2016| 7 Days DAY ONE s Lunch at MCL, Indianpolis. s Arrive at Gaylord Opryland Resort, Nashville, TN for a 2-night stay. Explore this incredible property including nine acres of indoor gardens, the Delta River area, restaurants, entertainment & more. s Enjoy dinner at the Backstage Grill where the waiters perform music! s L, D (c)EPE, Inc. DAY TW O Graceland s Full breakfast at Opryland. s Discover the “Athens of the South” - Nashville, on a guided tour. s Self-guided tour of Ryman Auditorium, original home of the Grand Ole Opry. s Board the General Jackson Showboat for lunch & live entertainment while cruising on the Cumberland River. s Visit the new Country Music Hall of Fame. s Free time to explore hotel & its many dining options. s Head over to the Grand Ole Opry and enjoy family entertainment featuring the best in country music. The Opry is America’s longest running live radio show! s B,L (c)EPE, Inc. DAY THREE s Full breakfast at Opryland hotel. s Visit Shiloh National Military Park, home to the Battle of Shiloh - one of the first major battles in the Civil War - resulting in nearly 24,000 killed. s Dinner at the Catfish Hotel. s Arrive at Doubletree Hotel, downtown Memphis, TN for a 3-night stay. s B, D (c) Grand Ole Opry DAY FO UR s Full breakfast at hotel. s Unique tour of Memphis, the birthplace of rock’n’roll and the home of the blues, led by a professional guide who uses music, comedy, and song to create a one-of-a-kind touring experience. -

7'1Te EVERGREENEWS

7'1te EVERGREENEWS A .~Veigh6orlworl AetPspoper Sponsored 6y Vollintine- Evergreen Community Action Association the city of Memphis as a whole. And it is time for Memphis to come together as a whole and stop dividing itself off. 2. I do plan to involve the whole community and community groups Political Poop in the process. MARY JANE BURT, WILLIAM M. LARSHA, and J. 0. PAT This fall marks the start of a new political season. In ad TERSON (incumbent) - No Response. dition to numerous City Councilmen, school board members, mayoral candidates and judges VECCA residents will be voting for a County Mayor for the first time on October 9th. At-Large Position 1 To introduce the at-large and VECCA district candidates for City Council The Evergreen News circulated a question BONNY MARTIN naire which asked the following: Background: Board of Directors, LeDonhcur Hospital; Com 1. What is the single most important problem facing mid missioner, Memphis Park Commission; Shelhy Farms Plan town and how would you solve it? ning Board. 2. Do you plan to involve neighborhood groups in the City's Positions: 1. I would be willing to listen to responsible groups planning process? representing this area who can identify the problems and work lie re is a summary of the answers we received. toward solutions. 2. Yes, by listening to responsible groups. City Council BETTY BOUTON SMITH District 5 Positions: 1. Retain the good and improve the not so good. Clean up repair and maintain services, good street lighting JIM FIELDS and public safety. Do these things and then increase civic pride Background: Discjockey, advertising executive. -

Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) City by City Guide for J-1 Exchange Visitors

Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) City by City Guide for J-1 Exchange Visitors Updated Fall 2018 On the following pages, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) has compiled a listing of various potential cultural activities in key cities across the United States. This list is for informational purposes only and is not an exhaustive list of available activities in a particular city. We recommend also contacting your local Visitors Bureau to discover additional activities or resources that might be of particular interest to you. Also, please note that resource URLs may change so if a link does not work properly utilize an internet search engine to find the correct link for the item you are looking for. If you don’t see your city listed or would like SHRM to help you find resources in your community, please email us at [email protected]. 1 Table of Contents: Atlanta, GA 3 Marshalltown, IA 30 Austin, TX 5 Memphis, TN 31 Birmingham, AL 6 Miami, FL 32 Boston, MA 7 Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN 33 Buffalo, NY 8 Nashville, TN 34 Charlotte, NC 9 New Orleans, LA 35 Charleston, SC 10 New York City, NY 37 Chicago, IL 11 Orlando, FL 39 Cincinnati, OH 13 Phoenix, AZ 40 Cleveland, OH 14 Philadelphia, PA 41 Columbus, OH 15 Pittsburgh, PA 44 Corning, NY 16 Portland, OR 45 Dallas, TX 17 Providence, RI 48 Denver, CO 18 Raleigh, NC 49 Des Moines, IA 20 Salt Lake City, UT 50 Detroit, MI 21 San Antonio, TX 51 Houston, TX 22 San Diego, CA 52 Indianapolis, IN 24 San Francisco, CA 53 Jacksonville, FL 25 San Jose, CA 55 Kansas City, MO 26 Seattle, WA 56 Knoxville, TN 27 St. -

Memphis Downtown

DOWNTOWNMap MUSIC z K-8 Ducks Unlimited : K-10 Backbeat Tours HOTELS & LODGING Waterfowling Heritage 1 K-10 Beale Street " K-10 Blues City Tours 1 K-8 Big Cypress Lodge Entertainment District Center Z K-10 Carriage Company 2 2K-9 Comfort Inn - Downtown 2 J-11 Blues Hall of Fame x B-5/L-13 Elmwood Cemetery C J-12 Historical Haunts 3 K-9 Courtyard by Marriott 3 J-10 Center for Southern Folklore c L-10 Mallory-Neely House Downtown Court Square V J-9 Memphis Best Tours, Inc. 4 K-11 Gibson Beale Street m J-12 Memphis Railroad & 4 K-9 Crowne Plaza Memphis B K-10 Memphis Hop Showcase Factory Tours Trolley Museum Downtown N J-11 Old Dominick Distillery 6 K-10 Memphis Music Hall of Fame , I-13 Metal Museum 5 K-10 DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel M Rockabilly Rides 7 K-11 Memphis Rock ‘n’ . J-9 Mississippi River Museum at J-10 Memphis Downtown Soul Museum Mud Island River Park < L-10 Sprock n’ Roll 6 K-10 Downtown Vista Inn & Suites 8 B-5/L-13 Stax Museum of @ J-11 National Civil Rights > K-10 Tastin’ ‘Round Town 7 K-10 EconoLodge Downtown American Soul Music Museum 8 K-10 The Exchange 9 L-10/11 Sun Studio # K-8 Slave Haven Underground ENTERTAINMENT VENUES, 9 K-10 Hampton Inn & Suites Railroad Museum 0 K-10 W.C. Handy Home & Museum STAGES & ARENAS Memphis - Beale Street (Burkle Estate) 4 K-10 AutoZone Park, Home of the 0 K-10 Holiday Inn Downtown ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICTS $ St. -

Memphis! Memphis

Pick THE Perfect Place for Your Next Event CROWNE MEMPHIS DOWNTOWN DESTINATION & SPORTS PLANNING GUIDE PLAZA 300 North Second Street Memphis, TN 38105 901.525.1800 Fax 901.524.1859 www.cpmemphishotel.com Jack Kenner 2011 © Photo by Come Meet In Memphis Justin Fox Burks HOLIDAY INN SELECT - Downtown MemphisDOWNTOWN- Dan Ball 160 Union Avenue Memphis, TN 38103 901.525.5491 901.529.9141 Fax Phillip Parker www. hisdowntownmemphis.com Justin Fox Burks SM Jack Kenner www.Meetings.MemphisTravel.com Memories made fresh daily. The Peabody has been the South’s Grand Hotel for over 140 years. Unparalleled in its luxury, elegance and service, The Peabody remains the pinnacle of what glorious, historic hotels are all about. Make your own memories, create your own bit of history. ® ® 149 Union Avenue . Memphis, Tennessee 38103 901.529.4000 . 1.800.PEABODY www.peabodymemphis.com INFORMATION ON THE WEB If you’re a MEETING PLANNER and want SCAN IT to hold an event in Memphis, you can submit your RFP by fi lling out our online form or uploading a document with your meeting specifi cations. If you’re a TOUR OPERATOR bringing SCAN IT a group to town, check out our itineraries on topics like Memphis music, dining and culture. You can follow them exactly or mix and match attractions for your group. If you’re a SPORTS PLANNER wanting SCAN IT to host your next tournament or event in Memphis, you can check out different venues, search popular YOUR HOME FOR MEETINGS sporting events and contact our ON THE COURT. AND OFF. -

Private Commercial Law in the Cotton Industry: Creating Cooperation Through Rules, Norms, and Institutions

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2001 Private Commercial Law in the Cotton Industry: Creating Cooperation Through Rules, Norms, and Institutions Lisa Bernstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa Bernstein, "Private Commercial Law in the Cotton Industry: Creating Cooperation Through Rules, Norms, and Institutions," 99 Michigan Law Review 1724 (2001). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRIVATE COMMERCIAL LAW IN THE COTTON INDUSTRY: CREATING COOPERATION THROUGH RULES, NORMS, AND INSTITUTIONS Lisa Bernstein* The cotton industry has almost entirely opted out of the public le- gal system, replacing it with one of the oldest and most complex sys- tems of private commercial law Most contracts for the purchase and sale of domestic cotton, between merchants or between merchants and mills, are neither consummated under the Uniform Commercial Code ("Code") nor interpreted and enforced in court when disputes arise. Rather, most such contracts are concluded under one of several pri- vately drafted sets of contract default rules and are subject to arbitra- tion in one of several merchant tribunals. Similarly, most international sales of cotton are governed neither by state-supplied legal rules nor * Professor, University of Chicago Law School. B.A. University of Chicago, J.D. Harvard. - Ed. Special thanks are due to Douglas Baird and Omri Ben-Shahar for their ex- tensive commentary and critique, and to my mentor, teacher, and friend David Charny, who first got me interested in nonlegal sanctions. -

5144722750 Methodist Healthcare

METHODIST HEALTHCARE-MEMPHIS Memphis, TN | EIN: 62-0479367 | Number: 5144722750 Methodist Healthcare - Memphis Hospitals Is A 501(C)(3) Non-Profit O ... Healthcare Delivery System Based In Memphis, Tennessee The First Methodist Hospital ... In The Mid-South Affiliated With The Memphis, Mississippi And Arkansas Conferences ... GROSS RECEIPTS $1,913,635,010 ASSETS $1,002,906,833 SHELBY COUNTY HEALTH CARE CORPORATION REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER AT MEMPHIS Memphis, TN | EIN: 62-1113169 | Number: 0097248299 Five-State Region Within 150 Miles Of The Memphis Area. Regional One Health Provides Access ... Center To Patients Within 150 Miles Of Memphis, And Is The Safety Net To The Region. ... GROSS RECEIPTS $427,975,452 ASSETS $322,683,411 BAPTIST MEMORIAL HEALTH CARE CORPORATION Memphis, TN | EIN: 58-1521475 | Number: 8346078631 Year, Making Baptist Operation Outreach Memphis' Largest Health Care Provider For The ... Working Together To End Homelessness In Memphis And Shelby County.Baptist Operation Outreach ... Thousands Of People Without Homes In Memphis, The Baptist Operation Outreach Van Is ... GROSS RECEIPTS $227,526,507 ASSETS $775,535, Memphis, TN | EIN: 58-1723645 | Number: 5726114022 ...community Memphis ... The mission of the Community Foundation of Greater Memphis is to strengthen ... offer scholarships to students from the Memphis area. Most scholarship opportunity we ... GROSS RECEIPTS $208,822,974 ASSETS $387,345,048 Community Foundation of Greater Memphis, Inc.Gold Memphis, TN | EIN: 58-1723645 | Number: 5726114022 ...community Memphis ... The mission of the Community Foundation of Greater Memphis is to strengthen ... offer scholarships to students from the Memphis area. Most scholarship opportunity we ... GROSS RECEIPTS $208,822,974 ASSETS $387,345,048 Hyde Family FoundationsBronze J.R. -

Taking in the Trail ® Carved by the Mighty Mississippi and Once the Western Boundary of America

memphis area self-guided driving tour Welcome to the Great River Road National Scenic Byway & Trail. SEE THE DRIVING TOUR MAP ON PAGE 12. Make your way along the western border of Tennessee taKing in the trail ® carved by THE mightY mississippi and once the western boundary of America. The Great River Road National Scenic • These 240 miles are full of historic sites, preserved homes and museums that bring the stories of the Great River Byway & Trail starts in Memphis, the southwestern most Road to life. Many of them require advance reservations, point in the state, and travels to the northwestern border admission or both to experience our history. at legEndarY Reelfoot Lake. The route from corner to • Many historic buildings, like Alex Haley’s boyhood home, corner is a part of the larger Great River Road National Scenic open their doors to visitors. Many properties remain Byway, a designated route spanning 10 states, from the as they have for over a century: private residences. Please be respectful of the private land and homeowners Mississippi River’s headwaters in Minnesota all the way to on our tour. the Gulf of Mexico. RIP? We’ve got • This is a drive that promises an off-the-beaten-path READY FOR A TENNESSEE ROAD T On the Tennessee portion, you’ll encounter small towns Tennessee experience. What we can’t promise is steady you covered on the new, self-guided driving trails of the full of history, local fare bursting with flavor, and Discover Tennessee Trails & Byways. On the Cotton Junction cell phone service.