Henry James and Ivan Turgenev: Cosmopolitanism, Croquet, and Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Croquet Rules

CONTENTS Page No. 2 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE GAME OF CROQUET “ 2 ASSOCIATION CROQUET 3 The Court, 4 Equipment, Centre Peg, Hoops, Balls, 5 A BRIEF OUTLINE OF THE GAME 6 Continuation Strokes, Ball in Hand, Foul Strokes 7 Penalty 8 The Grip. Standard Grip 8 Solomon Grip, Irish Grip 9 Stance. Centre Style, 9 The Strokes, Stance 10 The Roquet, The Cut Rush 11 Croquet Strokes. The Take Off 11 The Drive 12 The Stop Shot 12 The Roll Shot 12 The Split Shot 12 Jump Shot, Cannons 13 Hoop Running, 13 Angled Hoop 14 Margin of Error 14 The Start 16 Tactics 16 THREE & SIX PLAYER CROQUET 17 GOLF CROQUET 17 AMERICAN SIX WICKET CROQUET 18 The Court. The Start 18 Bonus Strokes, Dead and Alive 19 Rover Balls, Faults, Time Limit 20 NINE WICKET CROQUET 23 GLOSSARY A BRIEF HISTORY OF CROQUET 1 A game in which balls were knocked round a course of hoops was played in medieval France. A variation of the game known as "Paille Maille" was played in a field near St James Palace in the sixteenth century, which later became known as Pall Mall. The modern game appears to have started in England in the 1850s and quickly became popular. The Wimbledon All England Croquet Club was founded in 1868 and the National Championships were held there for a number of years until the croquet lawns were transformed into the tennis courts of today. This probably accounts for the fact that the size of a tennis court is exactly half that of a croquet lawn. -

By Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy Aleksey Tolstoy

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Упырь by Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy Aleksey Tolstoy. Russian poet and playwright (b. 24 August/5 September 1817 in Saint Petersburg; d. 28 September/10 October 1875 at Krasny Rog, in Chernigov province), born Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (Алексей Константинович Толстой). Contents. Biography. Descended from illustrious aristocratic families on both sides, Aleksey was a distant cousin of the novelist Lev Tolstoy. Shortly after his birth, however, his parents separated and he was taken by his mother to Chernigov province in the Ukraine where he grew up under the wing of his uncle, Aleksey Perovsky (1787–1836), who wrote novels and stories under the pseudonym "Anton Pogorelsky". With his mother and uncle Aleksey travelled to Europe in 1827, touring Italy and visiting Goethe in Weimar. Goethe would always remain one of Tolstoy's favourite poets, and in 1867 he made notable translations of Der Gott und die Bajadere and Die Braut von Korinth . In 1834, Aleksey was enrolled at the Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where his tasks included the cataloguing of historical documents. Three years later he was posted to the Russian Embassy at the Diet of the German Confederation in Frankfurt am Main. In 1840, he returned to Russia and worked for some years at the Imperial Chancery in Saint Petersburg. During the 1840s Tolstoy wrote several lyric poems, but they were not published until many years later, and he contented himself with reading them to his friends and acquaintances from the world of Saint Petersburg high society. At a masked ball in the winter season of 1850/51 he saw for the first time Sofya Andreyevna Miller (1825–1895), with whom he fell in love, dedicating to her the fine poem Amid the Din of the Ball (Средь шумного бала), which Tchaikovsky would later immortalize in one of his most moving songs (No. -

Master of the Mallet

NDEPTH ASTERof the WRITTEN BY JOSH GRAY ALLET PHOTOGRAPHY BY KIT NOBLE MTOP RANKED CROQUET PRO & FORMER TENNIS CHAMPION WAYNE DAVIES IS HOSTING AN INTERNATIONAL CROQUET TOURNAMENT AT THE WESTMOOR CLUB THIS AUGUST. N magazine magazine N 94 95 hat is the key ingredient to win- twinkle in his eye, “but it really relaxed me U.S. Opens once and nine times respectively. son. Davies will also be playing in the tour- applied for the job of sports director and be- ning as a professional athlete? Is before a big match.” All jokes aside, the ath- Although he was a strong athlete as a young nament. Over the last eight years, Davies has came its first employee. His first assignment it eating your Wheaties? Drinking lete chalks his successful career up to some man, Davies was injury prone and had to find become a top-ranked croquet player in the from developer and principal owner Graham Gatorade? If you ask Wayne Davies, it all very hard work and a penchant to learn every- a way to win on his own terms. “I’ve always United States. His path to playing croquet, Goldsmith was to learn to play croquet and be boils down to a good pint of beer. A former thing there is to know about his chosen sports. been a frenetic player,” he says. “I beat people however, wasn’t an easy one. able to teach it to the club’s members. world-champion “real” tennis player and cur- A native of Geelong, Australia, about with my own style. -

Aussie Rules Croquet - 9

Aussie Rules Croquet - 9. Once the correct hoop is run all the balls become alive again. Fun with Social Distance 10. After a hit the striker plays the two 1. Aussie Croquet, initially called bonus shots from the position so Ricochet, was developed as a achieved. training game in South Australia. 11. Bonus shots do not accumulate; The flexibility of its rules suits it for rather, the aim is to build breaks COVID-19 challenges - it’s a fun from a sequence of bonuses. game with in-built social distance. 12. Bonuses and Breaks make the So in health terms R0➪ game great fun 2. The Coach who invented it, John 13. Each ball must run each hoop in the Riches, stresses its role as a training correct order and then hit the peg. method;yet its popularity has grown 14. Each hoop and the peg score one and Queensland, Victoria, New point for that player. South Wales, ACT and America all 15. The player with the most points after have thriving tournaments or club one hour precisely will be the matches. winner. 3. As in Golf Croquet, an Aussie Rules 16. When a player’s turn ends they must Singles game plays Blue, Red, immediately vacate the lawn and Black, and Yellow balls in that order; retire to their corner until their next Blue and Black play Red and Yellow. turn. 4. Each ball is started in turn by being 17. Players are always 2 +metres apart hit from midway through its first hoop 18. A short game is to run hoops into the lawn. -

THE REVOLUTIONARY TRADITION ENGL 315 Fall 2011 Instructor: Michaela Bronstein, [email protected] Monday/Wednesday 2.00-3.20

THE REVOLUTIONARY TRADITION ENGL 315 Fall 2011 Instructor: Michaela Bronstein, [email protected] Monday/Wednesday 2.00-3.20, BARR 102 Drop-in office hours: Monday 12-2, Johnson Chapel #5 (Please e-mail to schedule meetings at any other time.) I wish to speak out about several matters even though my artistry goes smash. What attracts me is what has piled up in my mind and heart; let it give only a pamphlet, but I shall speak out. —Fyodor Dostoevsky, letter regarding his novel Demons Revolutionist and reactionary, victim and executioner, betrayer and betrayed, they shall all be pitied together when the light breaks on our black sky at last. Pitied and forgotten … —Natalia Haldin, Under Western Eyes, Joseph Conrad Contrary to the hope Conrad’s character expresses, we have not forgotten either the historical revolutionaries or the works they inspired. While Dostoevsky feared that his novel was too politically pointed to be a lasting work of art, Demons today is more well-known than the incident on which the novel was based. In this course we will analyze the afterlives of nineteenth-century novels about revolutionaries—not just their continuing interest, but their constant reappearance in later works. Dostoevsky’s worries about his novel turning into a “pamphlet” raise a broad issue for the novel form: why would an author who wishes to address pressing social issues write a novel rather than an essay? How do authors reconcile the long aims of literature with the urgent claims of the political present? Revolutionaries often appeal to their authors precisely because they seem to represent much more than the social problem they seek to reform—whether they represent the influence of ideology upon character or the difficulty of human attempts to plot better lives for themselves and others, revolutionaries usually carry the weight of much more abstract ideas than their immediate social purposes. -

Croquet New Zealand 2018 Player Survey Summary

8/6/2018 Croquet New Zealand 2018 Player Survey Summary Croquet New Zealand 2018 PLAYER SURVEY SUMMARY Author: Executive Director Peer Review: Sport Development Officer Organisation Development Convenor Contents Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Summary of Findings........................................................................................................................... 3 Generic Information ........................................................................................................................... 4 Croquet Code Participation ................................................................................................................ 6 What would encourage people to try / participate in Association Croquet? .................................... 8 What discourages people from trying Association Croquet? .......................................................... 11 Tournament Participation ................................................................................................................ 13 Croquet New Zealand Activities ........................................................................................................ 15 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................ 16 Appendix A – The Questionnaire ..................................................................................................... -

Russian Literature from Pushkin to Dostoevsky

SLAV-R 263 / SLAV-R 563 Professor Jacob Emery Mon/Wed 2:30P-3:45 [email protected] Kirkwood Hall 212 BH 515: MW 4-5 or by appointment Russian Literature from Pushkin to Dostoevsky The course is summarized and its aims are set forth: This course is a literature seminar. It will teach us to become more appreciative, perceptive, and understanding readers, and to communicate our experience of literary texts in a compelling way. In the process, we will touch upon questions of Russian history and culture, literary and intellectual tradition, philosophy and ethics and religion. How do we account for the extraordinary, unprecedented outburst of creativity in 19th century Russia? Why do we read these books more than a hundred years after they were written, and what skills do we need to have as readers if we are to understand and enjoy artworks that were created in a different language and in a different time? How do these works engage philosophy and social thought, and how do these aspects relate to their literary form? Why do we read fiction—which is a polite word for things that are not true, or at least not true in the usual sense—and what can fiction do that other kinds of writing cannot? These questions are just for starters. There will be many more questions, and you will pose most of them yourselves. For some of these questions you will develop good working answers. In other cases you will only open the door onto knotty knotty knots of complex issues. But by the end of the semester you will have read and understood the major prose works of what is called the “Golden Age of Russian Literature,” and you will have a firm foundation in the historical context and literary concepts necessary to understand works like them. -

Autumn 2021 Edition

THE AUSTRALIAN CROQUET ONLINE MAGAZINE AUTUMN 2021 WORLD CROQUET DAY THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT May 1, 2021 Message from the outgoing ACA Board Chair Megan Fardon As the second edition of the ACA Gazette goes of knowledge and experience they bring to the online I have the privilege to address the croquet board. I would like to extend my gratitude to those community for the last time in my role as Chair of previous board members. I leave the board with the ACA Board. a great insight into this wonderful mallet sport of It has been an honour to hold the position of croquet. I am very proud of the body of work my Chair of the Board of Croquet Australia. My tenure on colleagues have undertaken and happy to leave the Board started as an initial director representing the organisation in good order. Western Australia. The acceptance of our new I wish my successors clear direction and every constitution saw the first nine-member Board come good wish as they administer our game. into being in March 2015. This was a move away Happy reading of this next edition. from an Executive Council. Over following years the Board has moved to a seven-member format. Yours in croquet I have worked alongside many fellow board Megan Fardon members, 16 in total and learned from the wealth Message from the ACA Board Chair Jim Nicholls I would firstly like to congratulate and welcome A lot of work has been completed to ensure we Barbara Northcott, KerriAnn Organ, Bernie Pfitzner can all achieve on and off the court in 2021 and and Alison Sharpe to the board, and thank Megan beyond. -

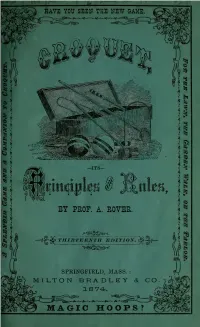

Croquet; Its Principles and Rules

HAVE YOU SEEN THE NEW GAME. BY PEOF. A. EOVEE. 1 ^ -^&^^i&^ -^: TELIRTEENTH EDITlOHf, >.. SPRINGFIELD, MASS MILTON BRADLEY & CO- 18 74 MAGIC HOOPS? ! Ladies ! Just the Paper for You THE PEETTIBST LADY'S PAPBS IH AMEEIOA. Send Stamp for Specimen Copy, Free^ Three exquisite GOOD KIGST, \ given to every Cliromos GOOD MORNING, ) Subscriber of AND Gems of the Flotver Garden, THE LADIES' FLORAL CABINET PICTOEIAL iome I Every number has fine illus- trations of flowers, gardens. hanging baskets, floral elegan- cies, and delightful home pic- tures of society, or household conveniences for the Ladies. Young Men and TVomen will find in it useful hints on self-improvement, manners, so- ciety, stories. ILadies will be interested in its designs for household work, dress, fashion, housekeeping, etc. ; music. Flower Liovers will be especially delighted with its directions about growing flowers, and window gardening. Tells them all about Bulbs, Hanging Baskets, Ferneries, Wardian Cases and Parlor Decorations. Try it. The prettiest of Family Pictorial Papers. Price $1.50 per year, including three chromos. 1.25 per year, including one chromo. Get up a Club. Premium List Free. Agents Wanted, Window Gardening.—A new book, superbly illustrated, devoted to culture of plants, bulbs and flowers, for the Window Garden; has 250 en- gravings and 300 pages. Price $1.50. Every Woman her own Flower Gardener, by Daisy Eyebright. A charming new book on flower and out-door gardening, for Ladies. Price 50 cents. your The Liadies' Cabinet Initial Note Paper, rose or violef tinted ; own initial. Superb novelty. Handsome present. Highly perfumed. At- tractive chromo on each box. -

Weekly Bulletin 20200121

Weekly Bulletin 20200121 District 9520 South Australia PO Box 340 MARDEN, SA 5070 Club website: https://portal.clubrunner.ca/stpeters facebook website: https://www.facebook.com/StPetersRotary/ Club phone: 08 8411 0277 Secretary: Pamela Vaughton President: John George Mobile: 0407 184 680 Mobile: 0414 824 232 Club email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Next Club Meeting – Tuesday 28th January 2020 at the Kensington Hotel Guest Speaker - Stacey Andary - Openlight Report of Meeting 3118 held on 21st January 2020 at the Glenunga Croquet Club Meeting Opening – Past President Brian Kretschmer opened the official Rotary meeting, welcomed guests including PDG Bob Cooper and several Kent Town Rotarians. He then handed over to Rotarian Chris Dawson, who is a member of the Glenunga Croquet Club and chief organiser of ‘Come and Try Croquet’ night. Page 1 of 7 Weekly Bulletin 20200121 Chris proceeded to explain how the players would be formed into groups of 4, each group to be under the guidance of a member of the croquet club. Most players were novices, however everyone soon got the idea of the game and some of the strategies involved. There was much banter and hilarity and the rules of the game allowed the Rotary ‘Four Way Test’ to be pushed to the limits. Page 2 of 7 Weekly Bulletin 20200121 It appeared that everyone, including the spectators, enjoyed the games and at the conclusion were well ready to partake of pizzas and a few drinks. Page 3 of 7 Weekly Bulletin 20200121 PDG Bob Cooper took the opportunity of presenting the Witches Hat Road Safety Cone that Bob had borrowed years ago from the Shed to David Heilbronn. -

Fathers and Sons Jessica Lee College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 14 Article 24 Spring 2016 Fathers and Sons Jessica Lee College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Lee, Jessica (2016) "Fathers and Sons," ESSAI: Vol. 14 , Article 24. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol14/iss1/24 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: Fathers and Sons Fathers and Sons by Jessica Lee (History 2225) he novel Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev showed the differing ideals between the old generation and the young generation and the paths they each felt Russia should be taking. TTurgenev showed through his characters that one does not nor should, as was also the case with Russia as a country, negate the past, thinking that would build a better future. He then showed another option; a happy marriage of the two ideals, where melding of the old Russia and the ideas of a new Russia produced a better and beneficial result. In fact, those characters in the book who represented opposite and far ends of the spectrum did not end with happy lives. In 1861 Alexander II moved forward with the first of many reforms by emancipating the serfs. This huge reform affected eighty-five percent of the population or about fifty-two million people.1 There were groups within Russia that were not happy about these changes, “they insisted on long-established values and fought bitterly to preserve privilege and autocratic rule.”2 The nobles and the Russian Orthodox Church made up the largest group that did not support the emancipation of the serfs. -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball