The Impacts and Benefits Yielded from the Sport of Quidditch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rugby World Cup Quiz

Rugby World Cup Quiz Round 1: Stats 1. The first eight World Cups were won by only four different nations. Which of the champions have only won it once? 2. Which team holds the record for the most points scored in a single match? 3. Bryan Habana and Jonah Lomu share the record for the most tries in the final stages of Rugby World Cup Tournaments. How many tries did they each score? 4. Which team holds the record for the most tries in a single match? 5. In 2011, Welsh youngster George North became the youngest try scorer during Wales vs Namibia. How old was he? 6. There have been eight Rugby World Cups so far, not including 2019. How many have New Zealand won? 7. In 2003, Australia beat Namibia and also broke the record for the largest margin of victory in a World Cup. What was the score? Round 2: History 8. In 1985, eight rugby nations met in Paris to discuss holding a global rugby competition. Which two countries voted against having a Rugby World Cup? 9. Which teams co-hosted the first ever Rugby World Cup in 1987? 10. What is the official name of the Rugby World Cup trophy? 11. In the 1995 England vs New Zealand semi-final, what 6ft 5in, 19 stone problem faced the English defence for the first time? 12. Which song was banned by the Australian Rugby Union for the 2003 World Cup, but ended up being sang rather loudly anyway? 13. In 2003, after South Africa defeated Samoa, the two teams did something which touched people’s hearts around the world. -

Itu World Cup Host City Bid Information 2021 Criteria Package

ITU WORLD CUP - HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 | 1 ITU WORLD CUP HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 CRITERIA PACKAGE INTERNATIONAL TRIATHLON UNION 2 | ITU WORLD CUP - HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 ITU WORLD CUP HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 CRITERIA PACKAGE CONTENTS Introduction 5 Host city opportunities 6 ITU’S investment and support services 7 Television and Media 9 Digital 9 Print media and photography 10 Spectators 11 Sustainability 11 Host city benefits 13 Host city requirements 13 Selection criteria 14 Bid schedule 15 Bid submission 15 ITU WORLD CUP - HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 | 3 4 | ITU WORLD CUP - HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 ITU WORLD CUP - HOST CITY BID INFORMATION 2021 | 5 INTRODUCTION Triathlon made its Olympic debut at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games and has since become one of the world’s fastest- growing sports. The International Triathlon Union (ITU), the sport’s worldwide governing body, introduced the Triathlon World Cup circuit to its program in 1990, one year after the organisation was established. With the creation of the World Triathlon Series in 2009, the Triathlon World Cup circuit became the ITU’s second-tier events. The World Cup circuit is a series of events comprising Standard distance (1.5km swim, 40km bike and 10km run), Sprint distance (750m swim, 20km bike and a 5km run) and two-day (semi-final/ final or Eliminator) format races. World Cup racing is intended to provide a strong and professional base for athletes pursuing entry to the World Triathlon Series and qualification for the Olympics Games and other Major Games. -

1 Palacký University in Olomouc Faculty of Physical Culture

Palacký University in Olomouc Faculty of Physical Culture Department of Adapted Physical Activity THE DETERMINANTS OF PARTICIPATION IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITIES AFTER THE WAR TRAUMA IN THE NATIONAL SITTING VOLLEYBALL TEAM OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Master Thesis Author: Bc. Mirza Pajević Mentor: Prof. Ph.Dr. Hana Valkova, CSc. Olomouc 2015 1 Bibliographical identification Author’s first name and surname: Mirza Pajević Tittle of the thesis: The determinants of participation in physical activity after the war trauma in Bosnian and Hercegovinian national sitting volleyball team Department: Adapted Physical Education Supervisor: Prof. PhDr. Hana Válková, CSc The year of presentation: 2015 Abstract: The purpose of this thesis was to examine the determinants that affect the reentry to physical activities after the war trauma in Bosnian and Hercegovinan national sitting volleyball team. I have analysed the effect of determinants on influance to sport activities and in relation to these determinants, I found out the approximate time period required for reentry to physical activities after trauma. This determinants are psycho-social. Using semi-structured interview I gained and evaluated data from 9 subjects, selected from Bosnian and Herzegovinian national sitting volleyball team, aged between 26 and 55 years. Major determinants, that had an effect on the return to physical activities, are discussed later. Amongst the determinants, I found the main as family, former friends, new friends with similar disabilities, hospitalization, rehabilitation center, economic situation, access to a vehicle, sport environment and influence of the intact society. The approximate time requires to return to physical activity with my selected sample is specified in the summary of this thesis. -

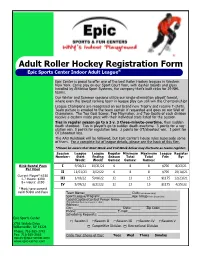

Inline Hockey Registration Form

Adult Roller Hockey Registration Form Epic Sports Center Indoor Adult League® Epic Center is proud to offer one of the best Roller Hockey leagues in Western New York. Come play on our Sport Court floor, with dasher boards and glass installed by Athletica Sport Systems, the company that’s built rinks for 29 NHL teams. Our Winter and Summer sessions utilize our single-elimination playoff format, where even the lowest ranking team in league play can still win the Championship! League Champions are recognized on our brand new Trophy and receive T-shirts. Team picture is emailed to the team captain if requested and goes on our Wall of Champions. The Top Goal Scorer, Top Playmaker, and Top Goalie of each division receive a custom made prize with their individual stats listed for the session. Ties in regular season go to a 3 v. 3 three-minute-overtime, then sudden death shootout. Ties in playoffs go to sudden death overtime. 3 points for a reg- ulation win. 0 points for regulation loss. 2 points for OT/shootout win. 1 point for OT/shootout loss. The AAU Rulebook will be followed, but Epic Center’s house rules supersede some of them. For a complete list of league details, please see the back of this flier. *Please be aware that Start Week and End Week below may fluctuate as teams register. Session League League Regular Minimum Maximum League Register Number: Start Ending Season Total Total Fee: By: Week: Week: Games: Games: Games: Rink Rental Fees I 9/06/21 10/31/21 6 8 8 $700 8/23/21 Per Hour II 11/01/21 1/02/22 6 8 8 $700 10/18/21 Current Player*:$150 -

Picking Winners Using Integer Programming

Picking Winners Using Integer Programming David Scott Hunter Operations Research Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, [email protected] Juan Pablo Vielma Department of Operations Research, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, [email protected] Tauhid Zaman Department of Operations Management, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, [email protected] We consider the problem of selecting a portfolio of entries of fixed cardinality for a winner take all contest such that the probability of at least one entry winning is maximized. This framework is very general and can be used to model a variety of problems, such as movie studios selecting movies to produce, drug companies choosing drugs to develop, or venture capital firms picking start-up companies in which to invest. We model this as a combinatorial optimization problem with a submodular objective function, which is the probability of winning. We then show that the objective function can be approximated using only pairwise marginal probabilities of the entries winning when there is a certain structure on their joint distribution. We consider a model where the entries are jointly Gaussian random variables and present a closed form approximation to the objective function. We then consider a model where the entries are given by sums of constrained resources and present a greedy integer programming formulation to construct the entries. Our formulation uses three principles to construct entries: maximize the expected score of an entry, lower bound its variance, and upper bound its correlation with previously constructed entries. To demonstrate the effectiveness of our greedy integer programming formulation, we apply it to daily fantasy sports contests that have top heavy payoff structures (i.e. -

2 Butts the Lacrosse Scoop Is a Technique Used to Gain Possession of the Ball When It Is on the Ground

Teaching Lacrosse Fundamentals Lacrosse Scoop -2 Butts The lacrosse scoop is a technique used to gain possession of the ball when it is on the ground. The scoop happens as a player moves toward the ball. It is the primary ball recovery technique when a ball is loose and on the ground. In order to perform it the player should drop the head of the stick to the ground and the stick handle should almost but not quite parallel with the ground only a few inches off the ground. The concept is similar to how you would scoop poop (pardon the expression) with a shovel off the concrete. With a quick scoop and then angle upward to keep the ball forced into the deep part of the pocket and from rolling back out. Once in the pocket the player will transition to a cradle, pass, or shot. Recap & Strategies: • Groundball Technique – One hand high on stick, other at butt end – Foot next to ball – Bend knees – 2 butts low – Scoop thru before ball • Groundball Strategies – 1-on-1 –importance of body position - 3 feet before ball can create contact and be physical – 1 –on -2 – consider a flick or kick to a teammate in open space – Scrum – from outside look for ball – get low and burst thru middle getting low as possible – If getting beat to a groundball to drive thru the butt end of the stick – 2–on-1 – man – ball strategy • one person take man, one take ball • Player closest to the ball must attack the ball as if there is no help until communication occurs • Explain the teammate behind is the “QB” telling the person chasing the ball what to do – ie “Take the Man” means turnaround and hinder the opponent so your teammate can get the ball. -

A Look at the Leagues That Saved Baseball on Two Continents Nate Manuel for American Baseball Perspective Thursday, July 30, 2014 UPDATED Sunday, February 12, 2017

A Look at the Leagues that Saved Baseball on Two Continents Nate Manuel for American Baseball Perspective Thursday, July 30, 2014 UPDATED Sunday, February 12, 2017 By the mid-2000s, even its most ardent supporters could read the writing on Major League Baseball’s wall. A lack of fiscal discipline had pushed player salary expectations to a point where only a select few teams could afford to field a competitive roster. Teams counting on gate and media revenue to foot the bill were in for a shock. After the heady highs of the 90s “Age of Offense”, fans disillusioned from countless scandals and revelations of steroid abuse expressed their frustration by staying home and spending their merchandising dollars elsewhere. With ratings sharply in decline, lucrative national and regional Eight years ago, pro baseball in America was broadcast deals became hard to come by. In May of 2004, the first two teams seemingly in jeopardy missed payroll. MLB covered for the clubs, claiming it was a temporary setback. But another three teams would come up short before the season was over. By mid-2006, half of the league’s teams were in default, and seven had declared bankruptcy. Negotiations with the Players’ Association went nowhere. MLBPA took a hard line: Pay us what we deserve or we’ll find someone else who will. The intractability of both sides sealed the league’s fate. On November 5, 2006, the official announcement came: MLB was suspending all operations indefinitely. The plan was to restructure the league’s business model, work out a new unified media contract model, and resume play in 2007 after a brief delay from the normal start of the season. -

University of Washington Bothell Intramural Sports Ultimate Frisbee Rules

University of Washington Bothell Intramural Sports Ultimate Frisbee Rules Introduction: Ultimate is a non-contact disc sport played by two teams of seven players. The objective is to be the team that scores the most goals. A goal is scored when a player catches the disc in the end zone that their team is attacking. Ultimate is a self-officiated sport, it relies on the players to make all calls 1. EQUIPMENT ● Closed toe shoes must be worn. Rubber and molded cleats are permitted. ● Metal cleats are not permitted. ● Players are not allowed to wear headphones or jewelry of any kind. ● Teams must wear shirts or pennies of matching color. ● The Intramural Activities staff will provide a disc unless both teams agree on a different one. ● Participants must wear athletic attire 2. TEAMS ● Teams are made up of a maximum of seven players. ● A team may start the game with five players. ● If a team has more than seven players they may substitute under the following circumstances: After a goal is scored or if a player is injured. 3. TIMING ● The game consists of two 20-minute halves with a 3-minute halftime. ● The clock will only stop for a timeout or injury. ● Each team gets two timeout per half. ● A team may only call timeout if they are in possession of the disc. (Unless it is in- between goals). 4. OVERTIME ● There will be no overtime during regular season games. ● If a playoff game ends in a tie sudden death overtime period (3 minutes) will be played. 5. PULL ● Play starts at the beginning of each half and after each goal with a “pull.” A pull is when a player on the pulling team throws the disc towards the opposite goal line to begin play. -

Sports History in the British Library: Selected Titles

SPORT & SOCIETY The Summer Olympics and Paralympics through the lens of social science www.bl.uk/sportandsociety Sports history in the British Library: selected titles Any analysis of sport, sporting events and sports governance must inevitably take into account the historical events which underpin them. For sports researchers, the British Library has an unrivalled collection of resources covering all aspects of the subject and in many different media, from books describing sporting events, to biographies and autobiographies of grass roots and elite athletes; coaching manuals; sport yearbooks and annual reports; directories of athletics clubs; sports periodicals; newspaper reports; and oral history interviews with sports people, including Olympians and Paralympians. These materials cover a long period of sporting activity both in Great Britain and elsewhere in the world. Some early materials As a glance at the earliest editions of the British Museum Library subject index show, the term ‘sport’ in the 18th century (and for much of the nineteenth) usually referred to blood sports. Nevertheless the existence of such headings as Rowing, Bowls, Cricket, Football, and Gymnastics in these early indexes point to a longstanding role for sport -as currently understood - in British social life. As was the case in ancient times, sports might originate as forms of preparation for war (from 1338, when the Hundred year’s war with France began, a series of English kings passed laws to make football illegal for fear that it would consume too much of the time set aside for archery practice); but they could also represent the natural human desire for friendly competition, so that alongside the jousting of the elite, games like bowling, stool ball and football could hold important places in the lives of ordinary people. -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings September 29, 2015 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1990 – The Reds clinch the Western Division when the second-place Dodgers lose to the Giants, 4-3. The Dodgers score is announced at Riverfront Stadium during a rain delay in the Reds-Padres game. The Reds emerge from the clubhouse to celebrate becoming the first National League team to lead for an entire 162-game schedule, with the rain soaked crowd. MLB.COM Reds struggle to back Finnegan in makeup game By Bill Ladson and Jacob Emert / MLB.com WASHINGTON -- Nationals right-hander Max Scherzer almost put himself in the record books Monday afternoon, coming within five outs of his second no-hitter of the season in a 5-1 victory over the Reds at Nationals Park. Scherzer allowed one run on two hits with 10 strikeouts and three walks over eight innings in a makeup of a game that was to be be played on July 8. Had Scherzer completed the no-hitter, he would have become the sixth pitcher to accomplish the feat twice in a season (including the postseason). The last to do it was Roy Halladay in 2010. Scherzer pitched his first no-hitter on June 20 in a 6-0 victory over the Pirates. "Scherzer had some great plays early," Nationals manager Matt Williams said. "The pitch count was in order. He was pushing it. I thought he was going to do it again. He pitched really well." Scherzer received plenty of help on defense. Tyler Moore, a first baseman by trade, made a great diving grab off the bat of Skip Schumaker in the third inning. -

John Michael Lang Fine Books

John Michael Lang Fine Books [email protected] (206) 624 4100 5416 – 20th Avenue NW Seattle, WA 98107 USA 1. [American Politics] Memorial Service Held in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, Together With Tributes Presented in Euology of Henry M. Jackson, Late a Senator From Washington. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983. 9" x 5.75". 457pp. Black cloth with gilt lettering. Fine condition. This copy signed and inscribed by Jackson's widow to a prominent Seattle journalist and advertising man: "Dear Jerry [Hoeck], I thought you would want to have a copy of this memorial volume. It comes with my deepest appreciation for your many years of friendship with our family and gratitude for your moving tribute to Scoop in the "Seattle Weekly" (p. 255.) sincerely Helen." (The page number refers to the page where Hoeck's tribute is reprinted in this volume.) Per Hoeck's obituary: "Hoeck's advertising firm] handled all of Scoop's successful Senatorial campaigns and campaigns for Senator Warren G. Magnuson. During the 1960 presidential campaign Jerry packed his bags and worked tirelessly as the advertising manager of the Democratic National Committee and was in Los Angeles to celebrate the Kennedy win. Jerry also was up to his ears in Scoop's two unsuccessful attempts to run for President in '72 and '76 but his last effort for Jackson was his 1982 senatorial re-election campaign, a gratifying landslide." $75.00 2. [California] Edwards, E. I. Desert Voices: A Descriptive Bibliography. Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1958. -

What Is Rookie Rugby? Fun, Safe Sporting Experience for Both Boys and Girls

Just pick up the ball and run with it! Rookie Rugby is the best way to be active and have fun with a new sport! Whether you are a teacher, former player, long-time supporter, or new to rugby, this game is for you! USA Rugby invites you to find your place in the rugby community - Rookie Rugby can be found in: * Physical Education Classes * After-School Programs * Recreational Leagues * Community Based Programs * State PE Conferences * Your Neighborhood! ‘Rugby For All’ begins with Rookie Rugby! What is Rugby? Game originated when William Webb Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it over 150 years ago in England! Today the game of rugby is played by over 3 million people in 120 countries across 6 continents! A version of rugby called Rugby Sevens has been included in the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janiero, Brazil. Rugby is a team “invasion” game where the object is to get the rugby ball past an opponents’ ‘Try Line’ and ground the ball. What is Rookie Rugby? Fun, safe sporting experience for both boys and girls Simple rules - the game is easy to learn and minimal equipment is required Promotes excellent skill development, teamwork, health, fitness, and most importantly – fun! Rookie Rugby Basics Object of game is to score a ‘try’ by touching the ball to the ground on or behind the goal line. Two hand touch or flags may be used Ball is passed sideways or backward only Free pass is used to start or a restart the game Play is free-flowing and continuous Rookie Rugby can be played in any indoor or outdoor open space Age and ability determines field size and duration of playing time Rookie Rugby is played between two teams of equal size, generally between 5 and 7 players to a team Boys and Girls play by the same rules Game uses ‘tags’ or ‘flags’ so little to no contact is made between players Playing the Game Rookie Rugby Honor Code Supporter/Parent Player 1) Honor the game in action and language.