Sir William Pepperell"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winslows: Pilgrims, Patrons, and Portraits

Copyright, The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine 1974 PILGRIMS, PATRONS AND PORTRAITS A joint exhibition at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Organized by Bowdoin College Museum of Art Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/winslowspilgrimsOObowd Introduction Boston has patronized many painters. One of the earhest was Augustine Clemens, who began painting in Reading, England, in 1623. He came to Boston in 1638 and probably did the portrait of Dr. John Clarke, now at Harvard Medical School, about 1664.' His son, Samuel, was a member of the next generation of Boston painters which also included John Foster and Thomas Smith. Foster, a Harvard graduate and printer, may have painted the portraits of John Davenport, John Wheelwright and Increase Mather. Smith was commis- sioned to paint the President of Harvard in 1683.^ While this portrait has been lost, Smith's own self-portrait is still extant. When the eighteenth century opened, a substantial number of pictures were painted in Boston. The artists of this period practiced a more academic style and show foreign training but very few are recorded by name. Perhaps various English artists traveled here, painted for a time and returned without leaving a written record of their trips. These artists are known only by their pictures and their identity is defined by the names of the sitters. Two of the most notable in Boston are the Pierpont Limner and the Pollard Limner. These paint- ers worked at the same time the so-called Patroon painters of New York flourished. -

The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740 Ronald P. Dufour College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dufour, Ronald P., "The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624699. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ssac-2z49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY IN COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS 1688 - 17^0 A Th.esis Presented to 5he Faculty of the Department of History 5he College of William and Mary in Virginia In I&rtial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Ronald P. Dufour 1970 ProQ uest Number: 10625131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10625131 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

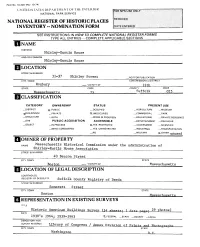

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1950, Volume 45, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE -. % * ,#^iPB P^jJl ?3 ^I^PQPQI H^^yjUl^^ ^_Z ^_^^.: •.. : ^ t lj^^|j|| tm *• Perry Hall, Baltimore County, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough Central Part Built 1773, Wings Added 1784 MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE larch - 1950 Jft •X'-Jr t^r Jfr Jr J* A* JU J* Jj* Jl» J* Jt* ^tuiy <j» J» Jf A ^ J^ ^ A ^ A •jr J» J* *U J^ ^t* J*-JU'^ Jfr J^ J* »jnjr «jr Jujr «V Jp J(r Jfr Jr Jfr J* «jr»t JUST PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY HISTORY OF QUEEN ANNE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND By FREDERIC EMORY First printed in 1886-87 in the columns of the Centre- ville Observer, this authoritative history of one of the oldest counties on the Eastern Shore, has now been issued in book form. It has been carefully indexed and edited. 629 pages. Cloth binding. $7.50 per copy. By mail $7.75. Published with the assistance of the Queen Anne's County Free Library by the MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 201 W. MONUMENT STREET BALTIMORE 1 •*••*••*•+•(•'t'+'t-T',trTTrTTTr"r'PTTTTTTTTTTrrT,f'»-,f*"r-f'J-TTT-ft-4"t"t"t"t--t-l- CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING Dftrkxr-BTKrTVTMn FRANK W. LINNEMANN BOOKBINDING 2^ Park Ave Magazines, medical books. Old books rebound PHOTOGRAPHY THE "^^^^ 213 West Monument Street, Baltimore nvr^m^xm > m» • ^•» -, _., ..-•-... „ Baltimore Photo & Blue Print Co PHOTOSTATS & BLUEPRINTS 211 East Baltimore St. Photo copying of old records, genealogical charts LE 688I and family papers. Enlargements. Coats of Arms. PLUMBING — HEATING M. NELSON BARNES Established 1909 BE. -

Descriptive Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings and of the Walker Collection

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Museum of Art Collection Catalogues Museum of Art 1930 Descriptive Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings and of the Walker Collection Bowdoin College. Museum of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection- catalogs Recommended Citation Bowdoin College. Museum of Art, "Descriptive Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings and of the Walker Collection" (1930). Museum of Art Collection Catalogues. 4. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection-catalogs/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum of Art at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Museum of Art Collection Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/descriptivecatal00bowd_2 BOWDOIN MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS WALKER ART BUILDING DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGUE OF THE PAINTINGS, SCULPTURE and DRAWINGS and of the WALKER COLLECTION FOURTH EDITION Price Fifty Cents BRUNSWICK, MAINE 1930 THE RECORD PRES5 BRUNSWICK, MAINE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE List of Illustrations 3 Prefatory Note 4 Historical Introduction 8 The Walker Art Building 13 Sculpture Hall 17 The Sophia Walker Gallery 27 The Bowdoin Gallery 53 The Boyd Gallery 96 Base:.:ent 107 The Assyrian Room 107 Corridor 108 Class Room 109 King Chapel iio List of Photographic Reproductions 113 Index ...115 Finding List of Numbers 117 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FACING PAGE Walker Art Building — Frontispiece Athens, by John La Farge 17 Venice, by Kenyon Cox 18 Rome, by Elihu Vcdder 19 Florence, hy Abbott Thayer 20 Alexandrian Relief Sculpture, SH-S 5 .. -

Universal Penman NEWSLETTER of the PROVIDENCE ATHENÆUM

Universal Penman NEWSLETTER OF THE PROVIDENCE ATHENÆUM MESSAGE FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, “Listen! The wind is rising, and the air is wild with leaves, ALISON MAXELL We have had our summer evenings, now for October eves!” Humbert Wolfe Ah, sweet Autumn - colorful foliage, crisp fall mornings, warm wool sweaters – my favorite time of the year. The shift in the seasons, the hint of promised change stirs my soul…and today I am grateful. This past spring you left us spellbound by your spirit and generosity – exceeding our Annual Fund expectations and sending us into the summer with promise and possibility. In early July we reviewed final recommendations from our consultancy and received news of Christina’s fellowship. Informed by both, we made the bold decision to suspend fall programming to enable board and staff to engage more deeply in the planning process – a strategic investment now of time and talent for the promise of a future filled with new possibility. By August, the Athenaeum became center stage - transforming from library to Hollywood set to construction site as members, tourists, artists, filmmakers, and contractors came and went. Suddenly, summer slipped by, students returned, a new semester began - the hustle and bustle of Benefit Street was back - fall had arrived. Inside the Athenaeum, leaves and crushed berries spot the carpets while the familiar scent of old books suggests you are home. Depending upon the day, Mary, Tina, Amy, Amanda, Kirsty, Kathleen, Stephanie or Morgan await your arrival, ready with the latest mystery, best seller, or biscuit (canines only)! Meanwhile, Mary Anne and Allen are upstairs ordering and cataloging the next batch of new books. -

Borrowing Privileges at 9 Historic Partner

Partner Membership Libraries The Athenaeum Music Devoted exclusively to music and art, featuring one of California’s & Arts Library most significant collections of artists’ books, the Athenaeum 1008 Wall Street presents a year-round schedule of art exhibitions, concerts, La Jolla, California 92037 lectures, classes, and tours. www.ljathenaeum.org Charleston Library Society A cultural institution for life-long learning, serving its members, 164 King Street community and scholars through access to its rich collections and Charleston, SC 29401 programs promoting discussion and ideas. www.charlestonlibrarysociety.org Folio: The Seattle Athenaeum A gathering place for books and the people who love them, 314 Marion St. offering vibrant conversations, innovative public programs, and Seattle, WA 98104 workspaces for writers and the intellectually curious. www.folioseattle.org The Mercantile Library Full of visits by authors and writers, book discussions, workshops, 414 Walnut Street, 11th Floor artworks and forums, there’s something on the schedule for all Cincinnati, OH 45202 bibliophiles. www.mercantilelibrary.com The Maine Charitable Mechanic Association Founded as a craftsman’s guild, MCMA provides support for 519 Congress Street mechanical and architectural education in local schools and a Portland, Maine 04101 popular series of travel lectures. Founded in 1815. www.mainecharitable mechanicassociation.org The New York Society Library 53 East 79th Street The city’s oldest library and home to a thriving community of New York, NY 10075 readers, writers, and families, founded in 1754. www.nysoclib.org The Portsmouth Athenaeum Located in the heart of historic Portsmouth, a library of over 9 Market Square 40,000 volumes and an archive of manuscripts, photographs, Portsmouth, N.H. -

Providence in the Life of John Hull: Puritanism and Commerce in Massachusetts Bay^ 16^0-1680

Providence in the Life of John Hull: Puritanism and Commerce in Massachusetts Bay^ 16^0-1680 MARK VALERI n March 1680 Boston merchant John Hull wrote a scathing letter to the Ipswich preacher William Hubbard. Hubbard I owed him £347, which was long overdue. Hull recounted how he had accepted a bill of exchange (a promissory note) ftom him as a matter of personal kindness. Sympathetic to his needs, Hull had offered to abate much of the interest due on the bill, yet Hubbard still had sent nothing. 'I have patiently and a long time waited,' Hull reminded him, 'in hopes that you would have sent me some part of the money which I, in such a ftiendly manner, parted with to supply your necessities.' Hull then turned to his accounts. He had lost some £100 in potential profits from the money that Hubbard owed. The debt rose with each passing week.' A prominent citizen, militia officer, deputy to the General Court, and affluent merchant, Hull often cajoled and lectured his debtors (who were many), moralized at and shamed them, but never had he done what he now threatened to do to Hubbard: take him to court. 'If you make no great matter of it,' he warned I. John Hull to William Hubbard, March 5, 1680, in 'The Diaries of John Hull,' with appendices and letters, annotated by Samuel Jennison, Transactions of the American Anti- quarian Society, II vols. (1857; repn. New York, 1971), 3: 137. MARK \i\LERi is E. T. Thompson Professor of Church History, Union Theological Seminary, Richmond, Virginia. -

Madam Wood's "Recollections"

Colby Quarterly Volume 7 Issue 3 September Article 3 September 1965 Madam Wood's "Recollections" Hilda M. Fife Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 7, no.3, September 1965, p.89-115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Fife: Madam Wood's "Recollections" Colby Library Quarterly Series VII September 1965 No.3 MADAM WOOD,'S "RECOLLECTIONS" By HILDA M. FIFE A MONG the earliest novelists in American literature is Sarah Sayward Barrell Keating Wood, known in her later years as Madam Wood. Born in York, Maine, on October 1, 17$9, at the home of her grandfather, Judge Jonathan Sayward, she married his clerk, Richard Keating, in 1778 and bore three children before his death in 1783. Then she began to write, publishing four novels in quick succession (Julia, or the Il luminated Baron, 1800; Dorval, or the Speculator, 1801; Amelia, or the Influence of Virtue, 1802; Ferdinand and El mira: A Russian Story, 1804), and later two long stories laid in Maine (Tales of the Night, 1827). She married General Abiel Woo,d in 1804 and lived in Wiscasset until his death in 1811. The rest of her life she spent in Portland, in New York, and in Kennebunk with various descendants. She died at the age of 95, still "a delightful companion to her great-great grandchildren, or to her nephews," according to her great grandson, Dr. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Boston a Guide Book to the City and Vicinity

1928 Tufts College Library GIFT OF ALUMNI BOSTON A GUIDE BOOK TO THE CITY AND VICINITY BY EDWIN M. BACON REVISED BY LeROY PHILLIPS GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 328.1 (Cfte gtftengum ^regg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS . BOSTON • U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Introductory vii Brookline, Newton, and The Way about Town ... vii Wellesley 122 Watertown and Waltham . "123 1. Modern Boston i Milton, the Blue Hills, Historical Sketch i Quincy, and Dedham . 124 Boston Proper 2 Winthrop and Revere . 127 1. The Central District . 4 Chelsea and Everett ... 127 2. The North End .... 57 Somerville, Medford, and 3. The Charlestown District 68 Winchester 128 4. The West End 71 5. The Back Bay District . 78 III. Public Parks 130 6. The Park Square District Metropolitan System . 130 and the South End . loi Boston City System ... 132 7. The Outlying Districts . 103 IV. Day Trips from Boston . 134 East Boston 103 Lexington and Concord . 134 South Boston .... 103 Boston Harbor and Massa- Roxbury District ... 105 chusetts Bay 139 West Roxbury District 105 The North Shore 141 Dorchester District . 107 The South Shore 143 Brighton District. 107 Park District . Hyde 107 Motor Sight-Seeing Trips . 146 n. The Metropolitan Region 108 Important Points of Interest 147 Cambridge and Harvard . 108 Index 153 MAPS PAGE PAGE Back Bay District, Showing Copley Square and Vicinity . 86 Connections with Down-Town Cambridge in the Vicinity of Boston vii Harvard University ... -

Daughters of the Nation: Stockbridge Mohican Women, Education

DAUGHTERS OF THE NATION: STOCKBRIDGE MOHICAN WOMEN, EDUCATION, AND CITIZENSHIP IN EARLY AMERICA, 1790-1840 by KALLIE M. KOSC Honors Bachelor of Arts, 2008 The University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, Texas Master of Arts, 2011 The University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, Texas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of AddRan College of Liberal Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 Copyright by Kallie M. Kosc 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to a great number of people, both personal and professional, who supported the completion of this project over the past five years. I would first like to acknowledge the work of Stockbridge-Munsee tribal historians who created and maintained the tribal archives at the Arvid E. Miller Library and Museum. Nathalee Kristiansen and Yvette Malone helped me navigate their database and offered instructive conversation during my visit. Tribal Councilman Jeremy Mohawk graciously instructed me in the basics of the Mohican language and assisted in the translation of some Mohican words and phrases. I have also greatly valued my conversations with Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Bonney Hartley whose tireless work to preserve her nation’s history and sacred sites I greatly admire. Numerous curators, archivists, and librarians have assisted me along the way. Sarah Horowitz and Mary Crauderueff at Haverford College’s Quaker and Special Collections helped me locate many documents central to this dissertation’s analysis. I owe a large debt to the Gest Fellowship program at the Quaker and Special Collections for funding my research trip to Philadelphia.