Protein Purification Process Engineering. Freeze Drying: a Practical Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Circuits (Guide) Niger

TI CIRCUITS, VOYAGES & SEJOURS TOURISTIQUES, SOLIDAIRES & CULTURELS, SAFARIS, ECOTOURISME 04B P 1451 Cotonou, Tel.: + (229) 97 52 89 49 / + (229) 95 68 48 49 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Blog: www.urbanotourisme.afrikblog.com Cotonou Benin, West Africa OUR CIRCUITS (GUIDE) NIGER. NB 1: through the information detailed well on sites (points of interests) tourist and cultural of the cities and villages of Niger below in which we work with our local partners among whom we have our own well experimented local guides, native of these circles, ready to make you live and discover their respective environment, you have the freedom total to conceive and to establish yourself, your journey, stay and circuit in Niger and to send him to us for its reorganization in our knowledge of the ground. NB 2: we are to hold you also at your disposal company in complete safety in cities and villages of Niger which are not included in our circuits Niger (guide) below. …………………………………………………………………………………… SUMMARY URBANO TOURISME, un partenaire sûr pour le développement et la promotion du tourisme au Bénin, Afrique & Monde OUR CIRCUITS (GUIDE) NIGER - TRADITIONAL HOLIDAYS & FESTIVALS IN NIGER - PRACTICAL INFORMATION NIGER. ........................................................................................................................... OUR CIRCUITS (GUIDE) NIGER. SUMMARY NIAMEY - NAMARO - ISLAND BOUBON - Tillabéry - AYOROU – KOMABONGOU - RESERVE FOR GIRAFFE Toure - PARK W - RESERVE TAMOU - THE DESERT TENERE - Agadez - RIVER NIGER - - Koutougou - Balleyara . ........................................................................................................................ THE NIGER RIVER REGION. 1 / Niamey : Niger's capital, Niamey, is a quiet town on the banks of the river. Far from the tumult of boiling and other major African cities , the atmosphere is relaxed and friendly atmosphere. -

Etat Des Lieux De La Riziculture Au Niger

Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger Elaboré par Sido Amir Novembre 2011 Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger Amir Sido / Assistant technique APRAO-Niger Niamey, Niger Abdoulkarim Alkaly, consultant, Niamey, Niger Abdou Maliki, consultant, Niamey, Niger Projet Amélioration de la production de riz en Afrique de l’Ouest en réponse à la flambée de prix des denrées alimentaires République du Niger Organisation des Nations unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture Agence espagnole de coopération internationale pour le développement ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ALIMENTATION ET L’AGRICULTURE Rome, 2011 Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ..................................................................................................................................... 3 AVANT-PROPOS ................................................................................................................................................. 6 REMERCIEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 8 1. CONTEXTE GENERAL ................................................................................................................................. 9 2. IMPORTANCE ECONOMIQUE -

The Snakes of Niger

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 9(2) [Special Section]: 39–55 (e110). The snakes of Niger 1Jean-François Trape and Youssouph Mané 1Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), UMR MIVEGEC, Laboratoire de Paludologie et de Zoologie Médicale, B.P. 1386, Dakar, SENEGAL Abstract.—We present here the results of a study of 1,714 snakes from the Republic of Niger, West Africa, collected from 2004 to 2008 at 28 localities within the country. Based on this data, supplemented with additional museum specimens (23 selected specimens belonging to 10 species) and reliable literature reports, we present an annotated checklist of the 51 snake species known from Niger. Psammophis sudanensis is added to the snake fauna of Niger. Known localities for all species are presented and, where necessary, taxonomic and biogeographic issues discussed. Key words. Reptilia; Squamata; Ophidia; taxonomy; biogeography; species richness; venomous snakes; Niger Re- public; West Africa Citation: Trape J-F and Mané Y. 2015. The snakes of Niger. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 9(2) [Special Section]: 39–55 (e110). Copyright: © 2015 Trape and Mané. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use for non-commercial and education purposes only, in any medium, provided the original author and the official and authorized publication sources are recognized and properly credited. -

Chapter 3: Current Situation of the Water Reservoir and Categorization

Chapter 3: Current situation of the water reservoir and categorization 3.1 Situation of the construction 3.1.1 First phase According to the document titled "Repertories of the main dams and their characteristics in Niger: September 2004" published by the Direction of Management and Rural Agricultural Equipment of the Ministry of Agricultural Development, during the first phase (2001-2002) of the Special Program of the President of the Republic, the construction of 54 water reservoirs was planned in the zone of this study. For one of these reservoirs, that of Angoual Denia, works do not yet start, although an advance on this work was given to the contractor. On the other hand, the reservoir of Aoka whose construction was planned 1 km upstream the water reservoir of Aboka changed destination during execution, and is used as dam to prevent from sand accumulation in the reservoir of Aboka, this makes it not possible to fulfill the functions of a water reservoir. In addition, a new additional reservoir, that of Edouk, was built. The reservoir of Guidan Bado remains always unfinished and the contract with the profit service provider for its construction was terminated to be given to another more able to complete it. Thus, today (August 2009), among 55 water reservoirs object of the first phase there existed in the area of this study 52 built reservoirs, and 1 reservoir almost completed although partially unfinished, making a total of 53 reservoirs. Table 3.1 (1) List of water reservoirs built during the first phase Number Water Region Department -

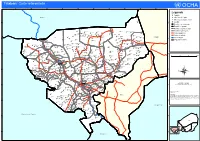

Ref Tillaberi A1.Pdf

Tillabéri: Carte référentielle 0°0'0" 0°30'0"E 1°0'0"E 1°30'0"E 2°0'0"E 2°30'0"E 3°0'0"E 3°30'0"E 4°0'0"E 4°30'0"E Légende !^! Capitale M a l i !! Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département N N " Digue Diga " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 Localité ° ° 5 5 1 1 Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Zongodey Frontière départementale Chinégodar Dinarha Tigézéfen Gouno Koara Chim Berkaouan Frontière communale In Tousa Tamalaoulaout Bourobouré Mihan Songalikabé Gorotyé Meriza Fandou Kiré Bissao Darey Bangou Tawey Térétéré Route goudronée Momogay Akaraouane Abala Ngaba Tahououilane Adabda Fadama Tiloa Abarey Tongo Tongo BANIBANGOU Bondaba Jakasa Route en latérite Bani Bangou Fondé Ganda Dinara Adouooui Firo ! Ouyé Asamihan N N " Tahoua " 0 Abonkor 0 ' Inates ' 0 Siwili Tuizégorou Danyan Kourfa 0 ° ° Fleuve Niger 5 Alou Agay 5 1 1 Sékiraoey Koutougou Ti-n-Gara Gollo Soumat Fadama ABALA Fartal Sanam Yassan Katamfransi ! Banikan Oualak Zérma Daré Doua I-n-Tikilatène Gawal Région de Tillabéri Yabo Goubara Gata Garbey Tamatchi Dadi Soumassou Sanam Tiam Bangou Kabé Kaina Sama Samé Ouèlla Sabon Gari Yatakala Mangaizé-Keina Moudouk Akwara Bada Ayerou Tonkosom Amagay Kassi Gourou Bossé Bangou Oussa Kaourakéri Damarké Bouriadjé Ouanzerbé Bara Tondikwindi Mogodyougou Gorou Alkonghi Gaya AYOROU Boni Gosso Gorouol ! Foïma Makani Boga Fanfara Bonkwari Tongorso Golbégui Tondikoiré Adjigidi Kouka Goubé Boukari Koyré Toumkous Mindoli Eskimit Douna Mangaïzé Sabaré Kouroufa Aliam Dongha Taroum Fégana Kabé Jigouna Téguey Gober Gorou Dambangiro Toudouni Kandadji Sassono -

The Use of Rural Radio to Test and Diffuse Extension Messages

The Use of Rural Radio to Test and Diffuse Extension Messages Prepared for USAID/Niger September 26, 1996 Submitted by: John Lichte Henry Hamilton Ouseini Kabo HERNS Delivery Order # 20 The Human and Educational Resources Network Support 4630 Montgomery Ave, Suite 600 Bethesda, MD 20814 Acknowledgments Many people have contributed to the success of this activity. We would like to thank Commandant Saley Moussa, Curt Nissly, David Miller and George Thompson for their support and assistance. We thank INRAN for the interest, support and participation ofTanimou Daouda, Mahamane Assoumane, and Abdoulaye Tahirou on the committee supervising these pilot ventures during a period of intense activity for INRAN. We would like to thank the Ministry of Agriculture for the participation of Ousman Abdou, from the Department of Agriculture's audio visual unit, and making Ouseini Kabo available for this exercise. We appreciate the participation ofFatmata Ousmane, from the AFRJCARE Goure project, throughout the activity. Finally we would like to thank the Nigerien Association of Radio Clubs for their efforts to make this activity a success, particularly, Na Awache Tambari, Secretary General, and Hassane Balla Kieta, who produced and recorded the actual extension messages in Zarma and Haoussa. Table of contents Acknowledgments . i Table of contents . 11 Acronyms . 1v Executive Summary ........................................................... v 1. Activity background and objectives ........................................ 1 1.1 Background ..................................................... 1 1.2 Revised Objective ................................................. 2 1.3 Approach ....................................................... 2 2. The use of radio for extension purposes .................................... 3 2.1 The importance of communication in extension ....................... 3 2.2 The evolution of the relationship between researchers, extension personnel and rural populations in Niger ..................................... -

Rural Societies in the Face of Climatic and Environmental Changes in West

Couv anglaisok Page 1 Scientific editors Benjamin Sultan, Richard Lalou, Mouftaou Amadou Sanni, Amadou Oumarou, Mame Arame Soumaré Rural societies in the face Benjamin Sultan, Richard Lalou Mouftaou Amadou Sanni Amadou Oumarou Mame Arame Soumaré of climatic and environmental changes in West Africa The future of West Africa depends on the capacity of its agriculture to ensure the food security of the population, which should double in the next 20 years,while facing up to the new risks resulting from climate warming. Indeed, the changes in temperature and precipita- tions already operating and that should become more marked will have serious effects on agricultural production and water resources in this part of Africa in the near future. One of the keys to meeting this new challenge is the adaptation of rural societies to climate risks. To gain better knowledge of the potential, processes and barriers, this book analyses recent and ongoing trends in the climate and the environment and examines how rural societies perceive and integrate them: what are the impacts of these changes, what vulnerabilities are there but also what new opportunities do they bring? How do the populations adapt and what innovations do they implement—while the climate- induced effects interact with the social, political, economic and technical changes that are in motion in Africa? By associating French and African scientists (climatologists, IRD agronomists, hydrologists, ecologists, demographers, geogra- 44, bd de Dunkerque phers, anthropologists, sociologists and others) in a multidisci- 13572 Marseille cedex 02 plinary approach, the book makes a valuable contribution to Rural societies in the face of climatic [email protected] better anticipation of climatic risks and the evaluation of African www.editions.ird.fr societies to stand up to them. -

NIGER Niger Only Seems to Make the News for Bad

© Lonely Planet 442 Niger Niger only seems to make the news for bad reasons: its recent coup, the Tuareg Rebellion, famine and – incredibly, as revealed in a trial in 2008 – its ongoing slavery problem. But if you make the effort to visit this desert republic, you’ll find a warm and generous Muslim population and some superb tout-free West African travel through ancient caravan cities at the edge of the Sahara. Sadly, at the time of writing the country’s greatest attractions, the Ténéré Desert and the Aïr Mountains in the north remained closed to travellers due to the Tuareg Rebellion. However, Libyan-brokered ceasefire talks between the Niger Movement for Justice (MNJ) and the government brought an end to the conflict, on paper at least, in 2009. The situation on the ground remains unstable, however, and you should always check the latest information before heading to the country’s north. Despite the closure of much of the county’s north, at the time of writing the fascinating trans-Saharan trade-route town of Agadez was still accessible, as well as a bevy of attractions in the peaceful south: the ancient sultanate of Zinder, the fantastic W National Park, West Africa’s last herd of wild giraffe at Kouré and the impossibly romantic Sunday market of Ayorou. Add to this the laid-back but cosmopolitan capital of Niamey and a trip down the mighty Niger River in a dugout pirogue, and you’ve got yourself a West African adventure NIGER NIGER that can cheerfully rival any other in this book. -

Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of the USAID West Africa Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Program

Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of the USAID West Africa Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Program January, 2015 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA) Consultancy Services. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The GIMPA Team is grateful to the many persons who helped to facilitate and expedite the work of the Team in this Mid-Term Evaluation of the USAID West Africa Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (USAID WA WASH) program. First and foremost, we want to express our deep appreciation for the guidance and accessibility provided by the USAID West Africa (USAID/WA) Mission and to all the various relevant stakeholders involved in USAID WA-WASH implementation. Specifically, our special thanks go to Dr. Jody Stallings, Ms. Georgette Atakorah, Dr. Daniel Nover, Mr. Collins Osae who provided us with technical feedback and the USAID WA-WASH team for their responses to some of our evaluation questions. Our sincere appreciation also goes to all the mayors and other government officials, chiefs, community leaders, and beneficiaries who took time from their busy schedules to be interviewed for this evaluation. They are all on the “front lines” of USAID WA WASH programs and their perspectives and opinions provided valuable insights. Many of their names appear in the List of Persons Interviewed in the Annexes of this document. i Mid-Term Performance Evaluation of the USAID West Africa Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Program Prepared under Task Order: SOL-624-14-000013 By: GIMPA Consultancy Services P.O. -

Boubon, Agadez Et Pratique De L'habbanaé Niger

Inventaires communautaires: Boubon, Agadez et pratique de l’Habbanaé Niger (2014-2015) Ministère de la Culture des Arts et des Loisirs Ce document reflète les résultats provisoires des exercices d’inventaires participatifs dans le cadre du projet de Renforcement des capacités du Niger pour la mise en œuvre de la Convention pour la sauvegarde du patrimoine culturel immatériel. Crédits Gouvernement du Niger Ministère de la Culture, des Arts et des Loisirs Monsieur Gambo Habou– Ministre Direction du patrimoine culturel et des Musées (DPCM) Monsieur Salou Abdou – Directeur Général et Monsieur Adamou Danladi- Directeur Bureau régional de l’UNESCO à Dakar Mme Guiomar Alonso, Chef de l’unité Culture Techniciens impliqués à l’élaboration d’inventaires - Mme Saidou Fati Boubacar, Chef de la Division du PCI - M. Hama Abdou, Chef de la Division des Musées - M. Maman Ibrahim, chef de Division, Direction des Arts et des Loisirs - Mme Nana Mariama Gambo Waziri Service civique national, Ministère de la Culture - Mme Hadjara Larabou, représentante de la communauté de Boubon - Mme Aîcha Abdou, représentante de la communauté de Boubon - M. Saidou Haladou, enseignant à Boubon et représentant de la communauté - M. Sidi Ahmed Tambari, représentant de la communauté d’Agadez - M. Ali Salifou, responsable du centre historique d’Agadez - M. Elhadj Ousmane Bianou, représentant de la communauté d’Agadez - M. Adamou Danladi, Directeur du Patrimoine culturel et des Musées - M. Abdoulaye Magé, Directeur Adjoint du Musée national Boubou Hama - M. Rhiskoua Gado, représentant de la communauté peulh de sallaga Bio (Tanout) - M. Bommo Djoumo, représentant de la communauté Teknewene (Tchintabaraden) - M. Abdoulaye Hassane représentant de la communauté de Boundou (Bermo) UNESCO - Section du patrimoine immatériel 1, rue Miollis – 75732 Fax: +33 1 45 685752 Cedex 15, France Email: [email protected] Tel: +33 1 45 684395 www.unesco.org/culture/ich Responsables du projet M. -

USAID Yalwa FY20 Annual Report

THE USAID YALWA ACTIVITY USAID AGREEMENT NUMBER: 72068520CA00003 FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2020 ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (MARCH 18, 2020 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020) Implemented by Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA) Submission Date: December 23, 2020 Submitted to: Doudou Ndiaye Acting Agreement Officer’s Representative (AOR) Deputy Director and Regional Agriculture Officer Sahel Regional Technical Office, USAID/Senegal Period of Performance: March 18, 2020 – March 17, 2025 This Annual Progress Report was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of CNFA and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 1 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS III 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. OVERVIEW OF ACHIEVEMENTS 3 3. ACTIVITIES IMPLEMENTED IN FY20 4 3.1 - PRODUCTION OF KEY TECHNICAL DELIVERABLES OF THE REFINEMENT PERIOD 4 3.2 – OTHER TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES OF THE REFINEMENT PERIOD 7 3.3 - COLLABORATIVE ACTIVITIES WITH USAID IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS 15 4. PROJECT MANAGEMENT 17 4.1 - PROJECT STAFFING 17 4.2 - OPERATIONS, FINANCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE START-UP 18 4.3 – PROJECT COMMUNICATIONS 19 4.4 – PROJECT REPORTING AND PLANNING 19 5. KEY PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED AND RESOLUTION 19 6. KEY SECURITY ISSUES/CONCERNS AND IMPACT ON INTERVENTIONS 20 7. PERFORMANCE IN FY20 AND PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING LOP PERFORMANCE RESULTS 20 ANNEXES 22 ANNEX 1 : LIST OF USAID YALWA, DFS, AND TEV INTERVENTION COMMUNES 22 ANNEX 2 : CHARACTERISTICS OF -

N I G E R 0 40 80 120 160 !( Small Town Or Acceptance by the United Nations

!( (! !( (! ! !(( 0°0'0" 5°0'0"E 10°0'0"E 15°0'0"E Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Algeria 20°0'0"N 20°0'0"N !( Aney EmiT chouma!( Achénouma !( !( Anefok Afassa !( !(!( Arrigui Zeloufiet !( ARLIT DIRKOUo (o! !( Bilma !( Goouuggaarraam TinT elloust (!!( Agadez Daannnneett (!!( Anou Zeggerin!( Tîmia!( Niger !( Adaouda Tasessat !( Mali !( Adouda !( !( Aouderas Tassessat !( Télouess !( !( Takazanza Akrérèb !( Abardok!( Germat !( !( !( Tessouma Edjouma !( Tegguiada In Tessoum Tagadaba !( Teguidda In Tagait Tabeidag Agessis !( Tin Dawin !( Diffa Chad TânoutA nghaïdé !( !( !( !( Aratène !( Tin Daoulne AGADEZ(!oAlarsas In Gall (! !( !( Gao !( !( Tilia TTcchhiinn TTaabbaarraaddeenn (! !( (! (! Tahoua !( !( Amerkay Efeinatas !( !(Assagueiguei Abalak Digue Diga Abalak (!!( (! Taza !( IIbbeesssseetteennee Assas!( Gouno Koara (!!( !( Bourobouré Zinder Bangou Tawey !( Meriza !( Takanamat (! !( Ngaba Tahououilane !( Tongo Tongo !( !( !( !( Abarey !( In Lelou !( Tiloa !( !( !( InA ouara Damtia !( !( Adabda (!BBaannii BBaannggoouu !( !( 15°0'0"N Firo Tuizégorou!( AAbbaallaa TAHOUA Guinia Maul 15°0'0"N (! Gollo!( !( Karkamat o! !( !( !( !( ( (! Zérma Daré Fadama !( Garagoumza !( Soumat (! Soumassou Ouèlla Sabon Gari Sanam In Karkada !( !( !( Tonkosom Tiam Kabé Kaina !( Garbey !( !( !( Edir !( Labandam TANOUT !( !( !( Mangahizé-Keina Tebaram !( (o! KEITA Mahaka !( Ouanzerbé TillaKabssi Geourroiu !( !( !( !( !( !( Tondikoiré Foïma Kaourakéri Gosso May Farin Kay !( !( !( !( !( In Tigar Ayorou Golbégui !( Makani !( Bagaroua !( o !(Téguey Taroum Bagaroua Maulela Tabotaki