Development Prospects of Niger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Circuits (Guide) Niger

TI CIRCUITS, VOYAGES & SEJOURS TOURISTIQUES, SOLIDAIRES & CULTURELS, SAFARIS, ECOTOURISME 04B P 1451 Cotonou, Tel.: + (229) 97 52 89 49 / + (229) 95 68 48 49 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Blog: www.urbanotourisme.afrikblog.com Cotonou Benin, West Africa OUR CIRCUITS (GUIDE) NIGER. NB 1: through the information detailed well on sites (points of interests) tourist and cultural of the cities and villages of Niger below in which we work with our local partners among whom we have our own well experimented local guides, native of these circles, ready to make you live and discover their respective environment, you have the freedom total to conceive and to establish yourself, your journey, stay and circuit in Niger and to send him to us for its reorganization in our knowledge of the ground. NB 2: we are to hold you also at your disposal company in complete safety in cities and villages of Niger which are not included in our circuits Niger (guide) below. …………………………………………………………………………………… SUMMARY URBANO TOURISME, un partenaire sûr pour le développement et la promotion du tourisme au Bénin, Afrique & Monde OUR CIRCUITS (GUIDE) NIGER - TRADITIONAL HOLIDAYS & FESTIVALS IN NIGER - PRACTICAL INFORMATION NIGER. ........................................................................................................................... OUR CIRCUITS (GUIDE) NIGER. SUMMARY NIAMEY - NAMARO - ISLAND BOUBON - Tillabéry - AYOROU – KOMABONGOU - RESERVE FOR GIRAFFE Toure - PARK W - RESERVE TAMOU - THE DESERT TENERE - Agadez - RIVER NIGER - - Koutougou - Balleyara . ........................................................................................................................ THE NIGER RIVER REGION. 1 / Niamey : Niger's capital, Niamey, is a quiet town on the banks of the river. Far from the tumult of boiling and other major African cities , the atmosphere is relaxed and friendly atmosphere. -

Niger Country Brief: Property Rights and Land Markets

NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison with Peter C. Bloch Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison Under Subcontract to Development Alternatives, Inc. Financed by U.S. Agency for International Development, BASIS IQC LAG-I-00-98-0026-0 March 2003 Niger i Brief Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of the country brief 1 1.2 Contents of the document 1 2. PROFILE OF NIGER AND ITS AGRICULTURE SECTOR AND AGRARIAN STRUCTURE 2 2.1 General background of the country 2 2.2 General background of the economy and agriculture 2 2.3 Land tenure background 3 2.4 Land conflicts and resolution mechanisms 3 3. EVIDENCE OF LAND MARKETS IN NIGER 5 4. INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS 7 4.1 The colonial regime 7 4.2 The Hamani Diori regime 7 4.3 The Kountché regime 8 4.4 The Rural Code 9 4.5 Problems facing the Rural Code 10 4.6 The Land Commissions 10 5. ASSESSMENT OF INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 11 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY 15 APPENDIX I. SELECTED INDICATORS 25 Niger ii Brief NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou with Peter C. Bloch 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE COUNTRY BRIEF The purpose of the country brief is to determine to which extent USAID’s programs to improve land markets and property rights have contributed to secure tenure and lower transactions costs in developing countries and countries in transition, thereby helping to achieve economic growth and sustainable development. -

The Mineral Industry of Mali and Niger in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook MALI AND NIGER [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior October 2019 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industries of Mali and Niger By Philip A. Szczesniak MALI refinery production), salt, and silver—represented only a minor part of the economy of Niger (International Monetary In 2016, the production of mineral commodities—notably Fund, 2017, p. 35, 67; World Nuclear Association, 2017). gold, but also cement—represented only a minor part of the The legislative framework for the mineral industry in Niger is economy of Mali (International Monetary Fund, 2017, p. 2, 5, provided by law No. 2006–26 of August 9, 2006, for its nonfuel 22, 24, 26). The legislative framework for the mineral sector in mineral sector and by law No. 2007–01 of January 31, 2007, Mali is provided by law No. 2012–015 of February 27, 2012. for its petroleum sector. Data on mineral production are in Data on mineral production are in table 1. Table 2 is a list of table 1. Table 2 is a list of major mineral industry facilities. major mineral industry facilities. More-extensive coverage of More-extensive coverage of the mineral industry of Niger can the mineral industry of Mali can be found in previous editions be found in previous editions of the U.S. Geological Survey of the U.S. Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook, volume III, Minerals Yearbook, volume III, Area Reports—International— Area Reports—International—Africa and the Middle East, Africa and the Middle East, which are available at which are available at https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/ https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/africa-and-middle-east. -

The Place of Bonny in Niger Delta History (Pp. 36-45)

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 5 (5), Serial No. 22, October, 2011 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v5i5.4 The Place of Bonny in Niger Delta History (Pp. 36-45) Orji, Kingdom E. - Department of History & Diplomatic Studies, Rivers State University of Education, Rumuolumeni, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Tel: +2348056669109 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Bonny occupies a strategic position in the Niger Delta Studies. Issues to be examined in this article include the circumstances surrounding the founding of this unique settlement on the Rio Real of Eastern Delta and its implications for the reconstruction of the history of other Niger Delta communities. An attempt will be made to unravel the strains encountered by the indigenous economy of our study area in the face of the assault of Old and New imperialism of the West from the fifteenth centuries to the recent past. Bonny’s strategic and pivotal role in the spread of Christianity in the study area is also highlighted. Early history The indigenous settlers of Bonny are known as the Ibani with a distinct language that goes by the same name. In fact the Ibani language has been classified under languages spoken in Eastern Ijo which themselves belong to the Ijoid group (Efere and Willamson 1989, pp. 43-44, Derefaka 2003, p. 23). Dike (1956, p.24) has given the impression that the Bonny are of Igbo origin. He suggest that the first migrants to this area, under their veritable leader Alagberiye himself, a distinguished hunter, had made incursions into this area between 1450–1800. -

Niger. Land, Politics: Light and Shade

N. 13 N.E. – SEPTEMBER OCTOBER 2009 REPORT Niger. Land, politics: Light and shade DOSSIER Tribes and Democracy. The apparent clash DISCOVERING EUROPE Lithuania looks more East than South The CThe magazine of Africa - Caribbeanurier - Pacific & European Union cooperation and relations Editorial Board Co-chairs Sir John Kaputin, Secretary General Secretariat of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States www.acp.int Mr Stefano Manservisi, Director General of DG Development European Commission ec.europa.eu/development/ Core staff Editor-in-chief Hegel Goutier Journalists Marie-Martine Buckens (Deputy Editor-in-chief) Debra Percival Editorial Assistant, Production and Pictures Research Joshua Massarenti Contributed in this issue Elisabetta Degli Esposti Merli, Sandra Federici, Lagipoiva, Cherelle Jackson, Francis Kokutse, Souleymane Saddi Maâzou, Anne-Marie Mouradian, Andrea Marchesini Reggiani, Okechukwu Romano Umelo and Joyce van Genderen-Naar Project Manager Gerda Van Biervliet Artistic Coordination, Graphic Conception Gregorie Desmons Public Relations Andrea Marchesini Reggiani Distribution Viva Xpress Logistics - www.vxlnet.be Cover Design by Gregorie Desmons Back cover Brazier, Niger, 2009. © Marie-Martine Buckens Contact The Courier 45, Rue de Trèves www.acp-eucourier.info 1040 Brussels Visit our website! Belgium (EU) You will find the articles, [email protected] Privileged partners www.acp-eucourier.info the magazine in pdf Tel : +32 2 2345061 and other news Fax : +32 2 2801406 Published every two months in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese For information on subscription, Go to our website www.acp-eucourier.info or contact [email protected] ultural centre promoting artists Cfrom countries in Europe, Afri- Publisher responsible ca, the Caribbean and the Pacific Hegel Goutier and cultural exchanges between Consortium communities through performance Gopa-Cartermill - Grand Angle - Lai-momo arts, music, cinema, to the holding of conferences. -

AREVA in 2007, Growth and Profitability

AREVA in 2007, growth and profi tability AREVA 33, rue La Fayette – 75009 Paris – France Tel.: +33 1 34 96 00 00 – Fax: +33 1 34 96 00 01 www.areva.com Energy is our future, don’t waste it! ACTIVITY AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT If you only have a moment to devote to this report, read this. Our energies have a future. A future without CO2 OUR MISSION no.1 worldwide Enable everyone to have access to ever cleaner, safer and more economical energy. in the entire nuclear cycle OUR STRATEGY To set the standard in CO2-free power generation and electricity transmission and distribution. no.3 worldwide ■ Capitalize on our integrated business model to spearhead in electricity transmission and distribution the nuclear revival: – build one third of new nuclear generating capacities; – make the fuel secure for our current and future customers. ■ Ensure strong and profi table growth in T&D. OUR PERFORMANCE IN 2007 ■ Expand our renewable energies offering. Backlog With manufacturing facilities in 43 countries and a sales network in more than 100, € +55.4% AREVA offers customers reliable technological solutions for CO2-free power generation and 39.83B electricity transmission and distribution. We are the world leader in nuclear power and the only company to cover all industrial activities in this fi eld. Sales Our 65,000 employees are committed to continuous improvement on a daily basis, making sustainable development the focal point of the group’s industrial strategy. €11.92B +9.8% AREVA’s businesses help meet the 21st century’s greatest challenges: making energy available to all, protecting the planet, and acting responsibly towards future generations. -

Etat Des Lieux De La Riziculture Au Niger

Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger Elaboré par Sido Amir Novembre 2011 Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’Alimentation et l’Agriculture Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger Amir Sido / Assistant technique APRAO-Niger Niamey, Niger Abdoulkarim Alkaly, consultant, Niamey, Niger Abdou Maliki, consultant, Niamey, Niger Projet Amélioration de la production de riz en Afrique de l’Ouest en réponse à la flambée de prix des denrées alimentaires République du Niger Organisation des Nations unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture Agence espagnole de coopération internationale pour le développement ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ALIMENTATION ET L’AGRICULTURE Rome, 2011 Etat des lieux de la riziculture au Niger TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ..................................................................................................................................... 3 AVANT-PROPOS ................................................................................................................................................. 6 REMERCIEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 8 1. CONTEXTE GENERAL ................................................................................................................................. 9 2. IMPORTANCE ECONOMIQUE -

NIGER State Report 1

INITIAL AND PERIODIC REPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NIGER TO THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS (A.C.H.P.R) ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 1988-2002 INTRODUCTION On 15th July, 1986 the Republic of Niger ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, adopted in Nairobi (KENYA) in June 1981. In compliance with article 62 of the Charter, Niger should have presented its initial report on measures taken with a view to giving effect to the rights and freedoms set out in the Charter. Also, the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th periodic reports should have been presented respectively in 1990, 1992, 1994, 1996, 1998 and 2000. The 7th report is scheduled to be presented this year. However difficulties of all sorts; military coup d’Etats, political instability and armed rebellions, as well as the socio-economic constraints that the country had to bear throughout the decade of the 1990s have not allowed the authorities of Niger to fulfil this obligation. By reason of the foregoing, the government of Niger fervently wishes that the present report be considered as a basic report, replacing all the other seven that Niger should have presented at the dates indicated above. The structure of the report, which is in line with the general guidelines drafted by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, is as follows: Chapter I: Profile of the Republic of Niger. Chapter II: Legal system, system of government and relations between institutions. Chapter III: Main texts of domestic law relating to the promotion and protection of Human and Peoples’ Rights. -

The Snakes of Niger

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 9(2) [Special Section]: 39–55 (e110). The snakes of Niger 1Jean-François Trape and Youssouph Mané 1Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), UMR MIVEGEC, Laboratoire de Paludologie et de Zoologie Médicale, B.P. 1386, Dakar, SENEGAL Abstract.—We present here the results of a study of 1,714 snakes from the Republic of Niger, West Africa, collected from 2004 to 2008 at 28 localities within the country. Based on this data, supplemented with additional museum specimens (23 selected specimens belonging to 10 species) and reliable literature reports, we present an annotated checklist of the 51 snake species known from Niger. Psammophis sudanensis is added to the snake fauna of Niger. Known localities for all species are presented and, where necessary, taxonomic and biogeographic issues discussed. Key words. Reptilia; Squamata; Ophidia; taxonomy; biogeography; species richness; venomous snakes; Niger Re- public; West Africa Citation: Trape J-F and Mané Y. 2015. The snakes of Niger. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 9(2) [Special Section]: 39–55 (e110). Copyright: © 2015 Trape and Mané. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use for non-commercial and education purposes only, in any medium, provided the original author and the official and authorized publication sources are recognized and properly credited. -

Chapter 3: Current Situation of the Water Reservoir and Categorization

Chapter 3: Current situation of the water reservoir and categorization 3.1 Situation of the construction 3.1.1 First phase According to the document titled "Repertories of the main dams and their characteristics in Niger: September 2004" published by the Direction of Management and Rural Agricultural Equipment of the Ministry of Agricultural Development, during the first phase (2001-2002) of the Special Program of the President of the Republic, the construction of 54 water reservoirs was planned in the zone of this study. For one of these reservoirs, that of Angoual Denia, works do not yet start, although an advance on this work was given to the contractor. On the other hand, the reservoir of Aoka whose construction was planned 1 km upstream the water reservoir of Aboka changed destination during execution, and is used as dam to prevent from sand accumulation in the reservoir of Aboka, this makes it not possible to fulfill the functions of a water reservoir. In addition, a new additional reservoir, that of Edouk, was built. The reservoir of Guidan Bado remains always unfinished and the contract with the profit service provider for its construction was terminated to be given to another more able to complete it. Thus, today (August 2009), among 55 water reservoirs object of the first phase there existed in the area of this study 52 built reservoirs, and 1 reservoir almost completed although partially unfinished, making a total of 53 reservoirs. Table 3.1 (1) List of water reservoirs built during the first phase Number Water Region Department -

Ref Tillaberi A1.Pdf

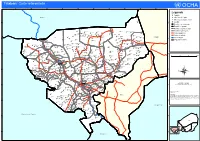

Tillabéri: Carte référentielle 0°0'0" 0°30'0"E 1°0'0"E 1°30'0"E 2°0'0"E 2°30'0"E 3°0'0"E 3°30'0"E 4°0'0"E 4°30'0"E Légende !^! Capitale M a l i !! Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département N N " Digue Diga " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 Localité ° ° 5 5 1 1 Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Zongodey Frontière départementale Chinégodar Dinarha Tigézéfen Gouno Koara Chim Berkaouan Frontière communale In Tousa Tamalaoulaout Bourobouré Mihan Songalikabé Gorotyé Meriza Fandou Kiré Bissao Darey Bangou Tawey Térétéré Route goudronée Momogay Akaraouane Abala Ngaba Tahououilane Adabda Fadama Tiloa Abarey Tongo Tongo BANIBANGOU Bondaba Jakasa Route en latérite Bani Bangou Fondé Ganda Dinara Adouooui Firo ! Ouyé Asamihan N N " Tahoua " 0 Abonkor 0 ' Inates ' 0 Siwili Tuizégorou Danyan Kourfa 0 ° ° Fleuve Niger 5 Alou Agay 5 1 1 Sékiraoey Koutougou Ti-n-Gara Gollo Soumat Fadama ABALA Fartal Sanam Yassan Katamfransi ! Banikan Oualak Zérma Daré Doua I-n-Tikilatène Gawal Région de Tillabéri Yabo Goubara Gata Garbey Tamatchi Dadi Soumassou Sanam Tiam Bangou Kabé Kaina Sama Samé Ouèlla Sabon Gari Yatakala Mangaizé-Keina Moudouk Akwara Bada Ayerou Tonkosom Amagay Kassi Gourou Bossé Bangou Oussa Kaourakéri Damarké Bouriadjé Ouanzerbé Bara Tondikwindi Mogodyougou Gorou Alkonghi Gaya AYOROU Boni Gosso Gorouol ! Foïma Makani Boga Fanfara Bonkwari Tongorso Golbégui Tondikoiré Adjigidi Kouka Goubé Boukari Koyré Toumkous Mindoli Eskimit Douna Mangaïzé Sabaré Kouroufa Aliam Dongha Taroum Fégana Kabé Jigouna Téguey Gober Gorou Dambangiro Toudouni Kandadji Sassono -

The Use of Rural Radio to Test and Diffuse Extension Messages

The Use of Rural Radio to Test and Diffuse Extension Messages Prepared for USAID/Niger September 26, 1996 Submitted by: John Lichte Henry Hamilton Ouseini Kabo HERNS Delivery Order # 20 The Human and Educational Resources Network Support 4630 Montgomery Ave, Suite 600 Bethesda, MD 20814 Acknowledgments Many people have contributed to the success of this activity. We would like to thank Commandant Saley Moussa, Curt Nissly, David Miller and George Thompson for their support and assistance. We thank INRAN for the interest, support and participation ofTanimou Daouda, Mahamane Assoumane, and Abdoulaye Tahirou on the committee supervising these pilot ventures during a period of intense activity for INRAN. We would like to thank the Ministry of Agriculture for the participation of Ousman Abdou, from the Department of Agriculture's audio visual unit, and making Ouseini Kabo available for this exercise. We appreciate the participation ofFatmata Ousmane, from the AFRJCARE Goure project, throughout the activity. Finally we would like to thank the Nigerien Association of Radio Clubs for their efforts to make this activity a success, particularly, Na Awache Tambari, Secretary General, and Hassane Balla Kieta, who produced and recorded the actual extension messages in Zarma and Haoussa. Table of contents Acknowledgments . i Table of contents . 11 Acronyms . 1v Executive Summary ........................................................... v 1. Activity background and objectives ........................................ 1 1.1 Background ..................................................... 1 1.2 Revised Objective ................................................. 2 1.3 Approach ....................................................... 2 2. The use of radio for extension purposes .................................... 3 2.1 The importance of communication in extension ....................... 3 2.2 The evolution of the relationship between researchers, extension personnel and rural populations in Niger .....................................