Lost in Transition. a Case of Delhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

University of Kerala Ba Music Faculty of Fine Arts Choice

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA COURSE STRUCTURE AND SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE IN MUSIC BA MUSIC UNDER FACULTY OF FINE ARTS CHOICE BASED-CREDIT-SYSTEM (CBCS) Outcome Based Teaching, Learning and Evaluation (2021 Admission onwards) 1 Revised Scheme & Syllabus – 2021 First Degree Programme in Music Scheme of the courses Sem Course No. Course title Inst. Hrs Credit Total Total per week hours credits I EN 1111 Language course I (English I) 5 4 25 17 1111 Language course II (Additional 4 3 Language I) 1121 Foundation course I (English) 4 2 MU 1141 Core course I (Theory I) 6 4 Introduction to Indian Music MU 1131 Complementary I 3 2 (Veena) SK 1131.3 Complementary course II 3 2 II EN 1211 Language course III 5 4 25 20 (English III) EN1212 Language course IV 4 3 (English III) 1211 Language course V 4 3 (Additional Language II) MU1241 Core course II (Practical I) 6 4 Abhyasaganam & Sabhaganam MU1231 Complementary III 3 3 (Veena) SK1231.3 Complementary course IV 3 3 III EN 1311 Language course VI 5 4 25 21 (English IV) 1311 Language course VII 5 4 (Additional language III ) MU1321 Foundation course II 4 3 MU1341 Core course III (Theory II) 2 2 Ragam MU1342 Core course IV (Practical II) 3 2 Varnams and Kritis I MU1331 Complementary course V 3 3 (Veena) SK1331.3 Complementary course VI 3 3 IV EN 1411 Language course VIII 5 4 25 21 (English V) 1411 Language course IX 5 4 (Additional language IV) MU1441 Core course V (Theory III) 5 3 Ragam, Talam and Vaggeyakaras 2 MU1442 Core course VI (Practical III) 4 4 Varnams and Kritis II MU1431 Complementary -

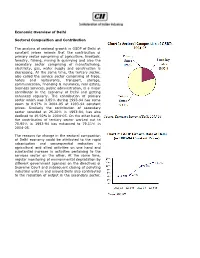

Economic Overview of Delhi Sectoral Composition and Contribution the Analysis of Sectoral Growth in GSDP of Delhi at Constant Pr

Economic Overview of Delhi Sectoral Composition and Contribution The analysis of sectoral growth in GSDP of Delhi at constant prices reveals that the contribution of primary sector comprising of agriculture, livestock, forestry, fishing, mining & quarrying and also the secondary sector comprising of manufacturing, electricity, gas, water supply and construction is decreasing. At the same time, the tertiary sector, also called the service sector comprising of trade, hotels and restaurants, transport, storage, communication, financing & insurance, real estate, business services, public administration, is a major contributor in the economy of Delhi and getting enhanced regularly. The contribution of primary sector which was 3.85% during 1993-94 has come down to 0.97% in 2004-05 at 1993-94 constant prices. Similarly the contribution of secondary sector recorded at 25.20% in 1993-94, has also declined to 19.92% in 2004-05. On the other hand, the contribution of tertiary sector worked out to 70.95% in 1993-94 has enhanced to 79.11% in 2004-05. The reasons for change in the sectoral composition of Delhi economy could be attributed to the rapid urbanisation and consequential reduction in agricultural and allied activities on one hand and substantial increase in activities pertaining to the services sector on the other. At the same time, regular monitoring of environmental degradation by different government agencies on the directives of Supreme Court and subsequent closing of polluting industrial units in and around Delhi also contributed to the reduction of output in the secondary sector. Delhi's service sector has expanded due in part to the large skilled English-speaking workforce that has attracted many multinational companies. -

Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Punjab

Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Punjab Course Scheme For M.A. (History) 1 CENTRE FOR SOUTH AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (Including Historical Studies) Course structure-M.A. IN HISTORY % Weightage Semester I Marks Paper Course Title L T P Cr A B C D E Code HST. 501 Research F 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Methodology HST. 503 Indian Political C 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Thought HST. 504 Pre-History and C 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Proto-History of India HST. 505 Ancient India C 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 (600BCE-300CE) HST. XXX Elective Course I E* 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 IDC. XXX Inter- E 2 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 Disciplinary/Open (O)** Elective HST. 599 Seminar C 0 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 TOTAL SEM I - 24 24 - 600 Elective Courses (Opt any one courses within the department) HST. 511 Art and Architecture E* 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 of Ancient India HST. 512 Early State and E* 4 0 0 4 25 25 25 25 100 Society in Ancient India Interdisciplinary Course/Open Elective Offered (For other Centers) HST. 521 Harrappan E 2 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 Civilization (O)** HST. 522 Religion in Ancient E 2 0 0 2 15 10 10 15 50 India (O)** 2 Semester II % Weightage Marks Paper Course Title L T P Cr A B C D E Code HST. -

Alankar: First Year Coursepack

LEVEL ONE WORKSHEETS The activities of the worksheet must be completed by the students. They may refer to class notes and online resources. Completed worksheets should be submitted as part of the online theory exam in the last week of February. Unfinished worksheets may be submitted with the theory exam of the following year. 1. Concepts Mangalacharan: This is the very first item a student of Odissi learns. This is an invocatory item in which one pays tribute to Mother Earth, Lord Jagannath and other Gods, also with stanzas to welcome the audience and to thank one's Gurus. "Mangala" means goodness, and "charan" mean wishing. Mangalacharan's rhythmic sequence of steps forming the Bhumi Pranam (salutation to Mother Earth) and Trikhandi Pranam (three-fold salutation to God, the Guru, and the audience) will be completed. Bhumi Pranam: The lesson starts with an brief and respectful apology to the Earth, for we are about to spend the next hour stamping on her. Tribhanga: The dancer's body is divided into three bhangas along which deflections of the head, torso and hips can take place. The technique is built on the principle of an unequal division of weight and the shift of weight from one foot to the other. The movement of the head, the torso, the hips and the knees, are important. Hip deflection is the characteristic feature of this dance style. The tribhanga is one of the most typical poses of Odissi dancing. Chowka: In this stance, weight is equally distributed and altogether four right angles create a perfect geometrical motif. -

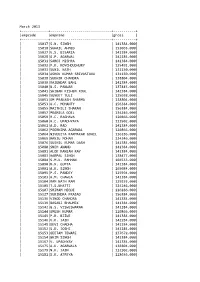

Rtisalmar13.Pdf

March 2013 +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ |empcode |empname |gross | +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ | 15017|S.N. SINGH | 141384.000| | 15018|SUHAIL AHMED | 153065.000| | 15027|V.S. BISARIA | 141384.000| | 15028|G.P. AGARWAL | 142184.000| | 15031|SAROJ MISHRA | 141384.000| | 15032|P.K. ROYCHOUDHURY | 125491.000| | 15033|SUNIL NATH | 131150.000| | 15034|ASHOK KUMAR SRIVASTAVA | 131150.000| | 15038|SUDHIR CHANDRA | 138804.000| | 15039|RAJENDAR BAHL | 141384.000| | 15040|B.S. PANWAR | 137445.000| | 15041|SHIBAN KISHEN KOUL | 142384.000| | 15045|SUNEET TULI | 125698.000| | 15051|OM PRAKASH SHARMA | 138804.000| | 15053|U.C. MOHANTY | 156384.000| | 15055|MAITHILI SHARAN | 156384.000| | 15057|PRAMILA GOEL | 134246.000| | 15059|R.C. RAGHAVA | 120866.000| | 15060|H.C. UPADHYAYA | 113502.000| | 15061|A.D. RAO | 141384.000| | 15062|POORNIMA AGARWAL | 120866.000| | 15064|NIVEDITA KARMAKAR GOHIL | 116186.000| | 15065|MANJU MOHAN | 134246.000| | 15076|SUSHIL KUMAR DASH | 141384.000| | 15080|SNEH ANAND | 141384.000| | 15081|ALOK RANJAN RAY | 141384.000| | 15083|HARPAL SINGH | 138477.000| | 15084|S.M.K. RAHMAN | 104533.000| | 15090|M.N. GUPTA | 141384.000| | 15091|A.K. SINGH | 165084.000| | 15095|P.S. PANDEY | 125594.000| | 15103|H.M. CHAWLA | 141384.000| | 15104|RAM NATH RAM | 129155.000| | 15105|T.S.BHATTI | 134246.000| | 15107|SRIRAM HEGDE | 116186.000| | 15127|SURINDRA PRASAD | 156384.000| | 15136|VINOD CHANDRA | 141384.000| | 15139|BASABI BHAUMIK | 141384.000| | 15142|G.S. VISWESWARAN | 141384.000| | 15144|UMESH KUMAR | 120866.000| | 15145|P.R. BIJWE | 141384.000| | 15146|V.K. JAIN | 142284.000| | 15148|DEVI CHADHA | 141384.000| | 15152|S.D. JOSHI | 141384.000| | 15153|GEETAM TEWARI | 137672.000| | 15154|BHIM SINGH | 141384.000| | 15167|V. -

July 2012 Edition

leb efJeÐeeled ogëKemeb³eesieefJe³eesieb ³eesiemebef%eleced Vol.XXVIII No.7 July, 2012 SUBSCRIPTION CONTENTS RATES 8 ` 500/- $ 50/- Editorial 2 Annual (New) 8 ` 1400/- Three Division of Yoga-Spirituality Brahmasutram 3 Year Decennial Celebrations of S-VYASA 4 8 ` 4000/- $ 500/- Bhajan Sandhya by Padmashree Anup Jalota 6 Life (10 years) Srimad Bhagawata Saptaham by Pujya Prema Pandurang Ji 8 Ganarchana – Prof. Paradesi Rao 12 Subscription in favour Division of Yoga & Life Sciences of ‘Yoga Sudha’, Dimensions of Yoga practices in HIV Bangalore by MO/ – Dr. Hemant Bhargav 13 DD only MIRT 17 Impact of 1 week of IAYT on diabetes: GDV measure 21 ADVERTISEMENT Division of Yoga & Physical Sciences TARIFF: Complete Color Research on Jyotish Astology & associated Astrological Front Inner - ` 1,20,000/- Influences... - Prof. Alex Hankey & Ramesh Rao 22 Back Outer - ` 1,50,000/- Hi am ‘FAST’ing, how can I help you? Back Inner - ` 1,20,000/- – Dr. B. Raghavendraswamy 23 Where is God - Manjeet Singh 24 Front First Inner Page - ` 1,20,000/- Division of Yoga and Management Studies Back Last Inner Page - Reader’s Forum 25 ` 1,20,000/- Yoga for Children – Dr. Tikhe Sham Ganapat 26 Full Page - ` 60,000/- YIC & ONCG SMET group 27 Half Page - ` 30,000/- Page Sponsor - ` 1,000/- Division of Yoga and Humanities Feel Free – Prof. K. Subrahmanyam 29 Dance Karanas: Perfection of Bharatha Natya Printed at: through Yoga – Mrs. Karuna Nagarajan 30 Sharadh Enterprises, Car Street, Halasuru, News Room Bangalore - 560 008 Pratishtapana of Sri Munishwara @ Giddenahalli -

Bhagavad Geeta – 13

|| ´ÉÏqÉ°aÉuɪÏiÉÉ || BHAGAVAD GEETA – 13 Yoga of the Field & Its Knower “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by TEXT SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA 28.13 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28.13 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse 13 ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11 Viveka Choodamani 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Isavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge A NOTE ABOUT SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities. -

Learning the Heart Way! Samyuktha

Learning the Heart Way! Samyuktha Samyuktha’s live-wire book, Learning the Heart Way , may dramatically alter the way young people think about college or university education in future. Most youngsters would like to be free of the drudgery and boredom associated with college lectures, mouldy professors, sterile guides and endless examinations. Coming from an ordinary middle-class environment in Andhra, Samyuktha decided to opt out of the ‘rat race of learning’: the endless tests and scores; the straitjacket imposed by college disciplines which actually narrowed down the world of learning to mugging badly written texts of history, political science, economics, psychology, and yes, sociology; the endless chase after MBA degrees. Instead, she created her own ‘higher education’ curriculum, one that suited both her heart and mind. The result is a marvellous book on learning’ as if the heart mattered’. Other India Press and Multiversity are delighted to be associated with a publication that will be a source of inspiration and direction to many young people (and their parents) in these days of heartless learning and soulless education. About the Author Samyuktha was born in August 1978 in New Delhi and went to school at Kalakshetra, Chennai. She trained as a handloom weaver by working with weavers in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, and subsequently learnt textile design at the National Institute of Fashion Technology. She is presently working with an enterprise of handloom weavers in Pochampalli cluster in Andhra Pradesh. She volunteers with social organizations and dreams of a world that is just and sustainable. Preface Samyuktha’s live-wire book, Learning the Heart Way, may dramatically alter the way young people think about college or university education in future. -

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List

PMAY (Urban) Beneficary List S.no Town Name Father_Name Mobile_No Pres_Address_StreetName 1 Jalesar BABY YASH PAL SINGH 7451085904 MOHALLA AKBARPUR HAVELI, JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 2 Jalesar MOHAR SHRI DEVI HAKIM SINGH 8006820002 BHAAMPURI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 3 Jalesar VIPIL KUMAR CHANDARPAL 7534009766 MOHALLA AKABRPUR HAWELI V.P.O JALESAR ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 4 Jalesar GUDDO BEGUM LAL KHAN 9568203120 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 5 Jalesar CHANDRVATI VIJAY SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 6 Jalesar POONAM BHARATI MIHALLA AKABARPUR 8869865536 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 7 Jalesar SAROJ KUMARI KUWARPAL SINGH 9690823309 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 8 Jalesar MOHAMMAD FAHIM MOHAMMAD SAHID 8272897234 MOHHALA KILA , JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 9 Jalesar SHAJIYA BEGAM BABLU 9758125174 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 10 Jalesar AMIT KUMAR DAU DAYAL BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 11 Jalesar KARAN SINGH LEELADHAR BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 12 Jalesar GUDDI NAHAR SINGH 9756578025 BRAMANPURI, JALESAR ETHA UTTAR PREDESH 13 Jalesar MADAN MOHAN PURAN SINGH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 14 Jalesar KANTI MUKESH KUMAR 9027022124 MOHALLA BARHAMAN PURI JALESAR ETHA 15 Jalesar SOMATI DEVI BACHCHO SINGH 7906607313 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 16 Jalesar ANITA DEVI SATYA PRAKESH AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, UTTAR PREDESH 17 Jalesar VIRENDRA SINGH AMAR SINGH 7500511574 AKBARPURI HAWELI, JALESAR, ETHA, -

Seminar 641, January 2013

Books THE PRICE OF LAND: Acquisition, Conflict, tunity cost’ of transplanting paddy, harvesting sugar- Consequence by Sanjoy Chakravorty. Oxford Uni- cane or picking cotton.2 During the latest Eleventh versity Press, New Delhi, 2013. Five Year Plan period ended 2011-12, farm wages on an all-India basis rose by an average 17.5 per cent per OF the four main ‘factors of production’ that go into annum. Even after adjusting for inflation, they went determining the cost of any commodity – land, labour, up by an unprecedented 6.8 per cent in real terms.3 capital and energy – the last two have always been con- While the 2000s have, no doubt, been transforma- sidered scarce and expensive in India. This, notwith- tive for labour – leading to an increase in overall standing government policies to underprice electricity, ‘reservation wages’, below which workers aren’t pre- diesel, cooking fuels and urea, or provide subsidized pared to accept employment – they have been even bank credit to farmers and other select borrower cate- more so, though, for land. It is this process – wherein gories. Such measures to keep capital and energy costs land in India has metamorphosed from just being an below their ‘normal’ market determined levels, in any incidental ‘factor of production’ to something whose case, have not been extended to industrial or commer- cost ‘can no longer be written out of the production cial consumers. Indian firms, in general, pay much more function’ – that Sanjoy Chakravorty’s book captures for availing working capital or term loan finance than most lucidly. It is by far the best work on a phenom- their counterparts in competing economies. -

Making Cities Work: Policies and Programmes in India

Making Cities Work: Policies and Programmes in India Debolina Kundu Arvind Pandey Pragya Sharma Published in 2019 Cover photo: Busy market street near Jama Masjid in New Delhi, India All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form by an electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission from the publishers. This peer-reviewed publication is suported by the GCRF Centre for Sustainable, Healthy and Learning Cities and Neighbourhoods (SHLC). The contents and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors. Although the authors have made every effort to ensure that the information in this report was correct at press time, the authors do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. SHLC is funded via UK Research and Innovation as a part of the Global Challenges Research Fund (Grant Reference Number: ES/P011020/1). SHLC is an international consortium of nine research partners as follows: University of Glasgow, Khulna University, Nankai University, National Institute of Urban Affairs, University of the Philippines Diliman, University of Rwanda, Ifakara Health Institute, Human Sciences Research Council and the University of Witwatersand Making Cities Work: Policies and Programmes in India Authors Debolina Kundu Arvind Pandey Pragya Sharma Research Assistance Sweta Bhusan Biswajit Mondal Baishali