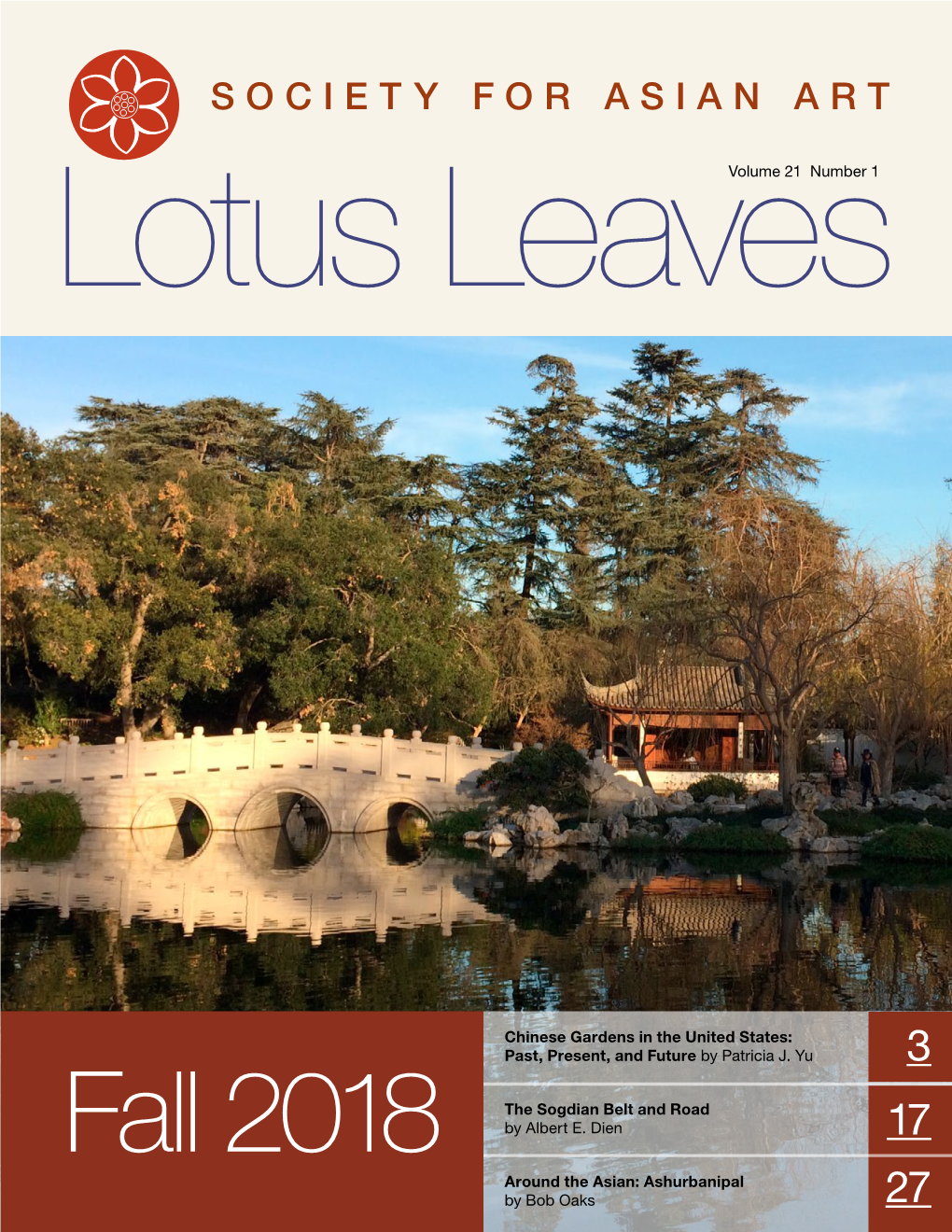

Lotus Leaves Fall 2018 Volume 21 Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montreal Architectural Review

Montreal Architectural Review Between Dream and Shadow: The Aesthetic Change Embodied by the Garden of Lion Grove Hui Zou University of Florida Abstract During the late 18th century, the Chinese emperor Qianlong ordered the construction of the Garden of Lion Grove and the Western Garden within his garden complex of Yuanmingyuan in Beijing. His Garden of Lion Grove was an imitation of the original Garden of Lion Grove in Suzhou, which was well known for its rockery labyrinth. Comparing the original Lion Grove and its replicas through poetry and architectural representation, Qianlong sought for truth of the cosmic world. My previous research has uncovered the cross-cultural history regarding the design of the Western Garden within the Yuanmingyuan. This essay translates and interprets the poems and garden records of the Lion Grove in Suzhou to reveal the aesthetic change of the garden from the original Buddhist Chan (Zen) idea of the Yuan dynasty to the secular labyrin- thine ecstasy of the Qing dynasty. The labyrinthine theatricality of the Lion Groves, including the original one and its replicas, was well documented by Qianlong through his poems and his frequent reference to master painter Ni Zan’s painting scroll of the Lion Grove in Suzhou. The essay draws a conclusion that the MAR Volume 5, 2018 6 Hui Zou | Montreal Architectural Review : Vol. 5, 2018 aesthetic transition from Buddhist Chan (Zen) to labyrinthine ecstasy at the Lion Grove in Suzhou took place in a particularly historical age, namely the Ming dynasty, when the philosophical issues of dream and fantasy became trendy in Chinese gardens and garden literature. -

Dear Friends, the Newport Flower Show Is Pleased to Celebrate Its

Dear Friends, The Newport Flower Show is pleased to celebrate its 18th year as America’s premier summer flower show, held on the historic grounds of Rosecliff. This year’s theme, Jade-Eastern Obsessions, will take visitors on an exotic tour of Far Eastern traditions and beauty. Jade, the imperial gemstone (valued as highly as gold and available in a rainbow of colors), is the perfect symbol for the 2013 Newport Flower Show. Exhibits will immerse you into cultures as varied and beautiful as the liquid forms of carved jade. It’s easy to understand why so many elements from these storied lands became Eastern Obsessions ! Joining us will be the inspirational floral designer Hitomi Gilliam who will share her masterful skills of the latest techniques and designs. As always, our Horticultural Division aspires to engage gardeners at all levels with opportunities to share their obsessions. East will meet west when notable American Landscape Architect, Harriet Henderson, shares her expertise and experiences throughout the Far East and explains how Western gardens have been influenced. Our Photography Division will provoke visitors with mysterious and haunting images from amateur photographers around the world. The Children’s Division will transport the youngest gardeners and designers to the exotic East where they too, can revel in Eastern Obsessions. The expansive front lawn of Rosecliff will lure visitors through an iconic Moon Gate into gardens filled with “Zen-full” inspirations. As always, shopping at the Oceanside Boutiques and the Gardener’s Marketplace are a much anticipated Newport tradition. The Opening Night Party will launch the summer season in Newport with a cocktail buffet, live music, a seaside supper and other surprises. -

Another World Lies Beyond Three Chinese Gardens in the US by Han Li

Another World Lies Beyond Three Chinese Gardens in the US By Han Li Moon door entrance to the Astor Court garden in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Wikimedia Commons at https://tinyurl.com/y6w8oggy, photo by Sailko. The Astor Court fter more than a decade in the making, a groundbreaking ceremo- Located in the north wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Astor ny took place for a grand classical Chinese garden in Washington, Court is the smallest yet arguably the most exquisite Chinese garden in DC, in October 2016. The US $100 million project, expected to be the US. The garden project was initiated for practical purposes. In 1976, Acompleted by the end of this decade, will transform a twelve-acre site at the Met purchased a set of Ming dynasty (1368–1644) furniture and con- the National Arboretum into the biggest overseas Chinese garden to date. templated a proper “Chinese” place to exhibit the new collection. This idea Interestingly, the report allures that the garden project is meant to implant of building a garden court was enthusiastically endorsed by Mrs. Brooke “a bold presence” of China near the US Capitol and “achieve for Sino-US Astor (1902–2007), a Metropolitan trustee and Astor Foundation chair- relations what the gift of the Tidal Basin’s cherry trees has done for Japa- person, who spent part of her childhood in Beijing due to her father’s nese-American links.”1 It is clear that such overseas Chinese gardens, in ad- naval posting. Thus, the genesis of the Astor Court project stems from dition to showcasing Chinese artistic and cultural expressions, also reflect the convergence of an institutional maneuvering and a sense of personal the particular social-historical circumstances under which they were con- nostalgia.2 The project was delegated to two Chinese architectural expert structed. -

Singapore Airlines Flies

JOURNALS china A N E T Following in M O the footsteps of China’s ancient P U roving royalty, TOM O’MALLEY E R discovers how the inspection R tours of old helped establish a O O template for travel in the Middle R’ F Kingdom today. S C H I N A A pedestrian bridge over West Lake cuts A a fine silhouette against a backdrop of stormy skies and undulating mountains in Hangzhou. 70 | SILVERKRIS.COM SILVERKRIS.COM | 71 JOURNALS china nlookers in scroll painting. Qianlong sacrifices and generally fine robes line was the sixth emperor of remind the provinces the edge of the the Qing Dynasty, ruling who’s boss. water as the from 1735 to 1796 in what Strictly speaking, a tourist magnificent was considered a golden is defined as one who travels Obarge cuts through the canal. age, where he beefed up for pleasure, but Qianlong In the background I spy grand China’s economy, expanded clearly had plenty of business pagodas and walled gardens its borders, and enhanced to take care of on route. And overhung by native ornamental cultural and intellectual life. yet, both Kangxi and Qianlong scholar trees. Elaborate He’s also, to my mind, China’s commissioned a set of 12 theatrical performances unfold greatest tourist. humongous scrolls – surely on stages along the shore, Qianlong and his the 18th century equivalent and the great Chang Gate in grandfather Kangxi revived of travel photography – to Suzhou, the Venice of the East, an Imperial tradition that recount the story of this stands ready to receive its most had fallen out of favour with ultimate pleasure cruise. -

A Dimensional Comparison Between Classical Chinese Gardens And

Yiwen Xu, Jon Bryan Burley, WSEAS TRANSACTIONS on ENVIRONMENT and DEVELOPMENT Patricia Machemer, April Allen A Dimensional Comparison between Classical Chinese Gardens and Modern Chinese Gardens YIWEN XU, JON BRYAN BURLEY, PATRICIA MACHEMER, AND APRIL ALLEN School of Planning, Design and Construction Michigan State University 552 West Circle Drive, 302 B Human Ecology Building, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA [email protected] http:/www.msu.edu/%7Eburleyj/ Abstract: Garden designers and scholars are interested in metrics that define the differences and similarities between traditional design and modern designs. This investigation examines the similarities and differences of classical Chinese gardens and modern Chinese gardens. The comparison is accomplished by ordinating the design elements and basic normative planning and design principles for each garden. Three classical Chinese gardens in Suzhou, Jiangsu, China and five modern gardens in Xiamen, Fujian, China were selected for study. A mathematical method called Principal Component Analysis (PCS) was applied in this research. The objective of this method is to define the dimensions that characterize the gardens and plot these gardens along the dimensions/gradients. Seventy-five variables were selected from a literature review, site visits, and site photos. According to the results of the PCA, there are potentially seven meaningful dimensions suitable for analysis, which explain 100% of the variance. This research focused on studying the first three principal components, explaining 81.54% of the variance. The first two principal components reveal a clear pattern between the two sets of environments. The results indicate that the first principal component can be a way to identify the difference between classical Chinese gardens and modern Chinese gardens. -

NAUMKEAG Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NAUMKEAG Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Naumkeag Other Name/Site Number: N/A 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 5 Prospect Hill Road Not for publication: City/Town: Stockbridge Vicinity: State: MA County: Berkshire Code: 003 Zip Code: 01262 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: _X_ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 10 buildings 11 sites 2 structures objects 23 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NAUMKEAG Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

Arbor, Trellis, Or Pergola—What's in Your Garden?

ENH1171 Arbor, Trellis, or Pergola—What’s in Your Garden? A Mini-Dictionary of Garden Structures and Plant Forms1 Gail Hansen2 ANY OF THE garden features and planting Victorian era (mid-nineteenth century) included herbaceous forms in use today come from the long and rich borders, carpet bedding, greenswards, and strombrellas. M horticultural histories of countries around the world. The use of garden structures and intentional plant Although many early garden structures and plant forms forms originated in the gardens of ancient Mesopotamia, have changed little over time and are still popular today, Egypt, Persia, and China (ca. 2000–500 BC). The earliest they are not always easy to identify. Structures have been gardens were a utilitarian mix of flowering and fruiting misidentified and names have varied over time and by trees and shrubs with some herbaceous medicinal plants. region. Read below to find out more about what might be in Arbors and pergolas were used for vining plants, and your garden. Persian gardens often included reflecting pools and water features. Ancient Romans (ca. 100) were perhaps the first to Garden Structures for People plant primarily for ornamentation, with courtyard gardens that included trompe l’oeil, topiary, and small reflecting Arbor: A recessed or somewhat enclosed area shaded by pools. trees or shrubs that serves as a resting place in a wooded area. In a more formal garden, an arbor is a small structure The early medieval gardens of twelfth-century Europe with vines trained over latticework on a frame, providing returned to a more utilitarian role, with culinary and a shady place. -

Indoor Outdoor Relationships at the Residential Scale

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2009 Indoor Outdoor Relationships at the Residential Scale Benjamin H. George Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation George, Benjamin H., "Indoor Outdoor Relationships at the Residential Scale" (2009). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 1505. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/1505 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDOOR OUTDOOR RELATIONSHIPS AT THE RESIDENTIAL SCALE by Benjamin H. George A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of of Master of Landscape Architecture in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning Approved : Michael L. Timmons Malgorzata Rycewicz-Borecki Major Professor Committee Member Steven R. Mansfield Committee Member UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2009 Copyright© Benjamin H. George 2009 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT INDOOR OUTDOOR RELATIONSHIPS AT THE RESIDENTIAL SCALE by Benjamin H. George, Master of Landscape Architecture Utah State University, 2009 Major Professor: Michael L. Timmons Department: Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning The indoor-outdoor relationship has been important to mankind since the dawn of recorded history. Over the ages, and despite continual changes in culture, style and technology, the relationship has continued to endure and play an important role in the design and construction of both interior and exterior spaces. -

Off* for Visitors

Welcome to The best brands, the biggest selection, plus 1O% off* for visitors. Stop by Macy’s Herald Square and ask for your Macy’s Visitor Savings Pass*, good for 10% off* thousands of items throughout the store! Plus, we now ship to over 100 countries around the world, so you can enjoy international shipping online. For details, log on to macys.com/international Macy’s Herald Square Visitor Center, Lower Level (212) 494-3827 *Restrictions apply. Valid I.D. required. Details in store. NYC Official Visitor Guide A Letter from the Mayor Dear Friends: As temperatures dip, autumn turns the City’s abundant foliage to brilliant colors, providing a beautiful backdrop to the five boroughs. Neighborhoods like Fort Greene in Brooklyn, Snug Harbor on Staten Island, Long Island City in Queens and Arthur Avenue in the Bronx are rich in the cultural diversity for which the City is famous. Enjoy strolling through these communities as well as among the more than 700 acres of new parkland added in the past decade. Fall also means it is time for favorite holidays. Every October, NYC streets come alive with ghosts, goblins and revelry along Sixth Avenue during Manhattan’s Village Halloween Parade. The pomp and pageantry of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in November make for a high-energy holiday spectacle. And in early December, Rockefeller Center’s signature tree lights up and beckons to the area’s shoppers and ice-skaters. The season also offers plenty of relaxing options for anyone seeking a break from the holiday hustle and bustle. -

A Cluster Analysis Comparison of Classical Chinese Gardens with Modern Chinese Gardens

ABSTRACT A CLUSTER ANALYSIS COMPARISON OF CLASSICAL CHINESE GARDENS WITH MODERN CHINESE GARDENS By Yiwen Xu Garden designers and scholars are interested in the differences and similarities between traditional design and modern designs. This investigation examines the similarities and differences of classical Chinese gardens and modern Chinese gardens. The comparison is accomplished by ordinating the design elements and basic principles for each garden. Three classical Chinese gardens in Suzhou, China and five modern gardens in Xiamen, China were selected to study. A mathematical method called Cluster Analysis was applied in this research. Seventy-five variables were selected from literature review and site photos. According to the result of Principal Component Analysis, the eigenvalues represent seven meaningful dimensions can be used for analysis. This research focused on studying the first two principal components for the garden comparison. The results indicate that the first principal component can be a way to identify the difference between classical Chinese gardens and modern Chinese gardens. The second principal component indicates the modern gardens can be grouped into two different categories. Keywords: Landscape Architecture, Environmental Design, Historic Gardens, Contemporary Gardens, Horticulture, Historic Preservation. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my major advisor Dr. Jon Burley, FASLA, Professor, Michigan State University School of Planning, Design and Construction, for his patient guidance and invaluable assistance through all stages of my work. I am grateful to my other two committee members, Dr. Patricia Machemer and Dr. April Allen, professors in Michigan State University School of Planning, Design and Construction, for all the advices, support and encouragement. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Cultivating Orientalism

The Newsletter | No.73 | Spring 2016 12 | The Study Cultivating Orientalism (1918-2000) in the late 1970s, the design team had proposed Although the transplantation of Chinese gardens to the Western world over that the ‘Late Spring Abode’ (Dianchun yi) in the western section of the ‘Garden of the Master of Nets’ (Wangshi yuan) the past few decades might appear far removed from the topic of Edward Said’s in Suzhou be recreated at the New York site. A long-defunct imperial ceramic kiln was reopened, a special team of loggers classic study, the cultural essentialism of which it partakes shares much with dispatched to the province of Sichuan to source appropriate timber, and a full-scale prototype constructed in Suzhou. Said’s original conception of Orientalism. But this is a form of Orientalism The garden was then meticulously assembled in New York early in 1980 by a team of Chinese experts, after a ritual exchange in which the power relationship has shifted dramatically. of hardhats with their American counterparts, before being officially opened to the public in June 1981. Stephen McDowall As if anticipating the “locus of infinite and unbridled creativity” that Bolton wants us to see at the Met, Chen Congzhou claimed that the opening of the Astor Court “served IN JUNE 1664, John Evelyn took an opportunity to view precisely for their lack of exoticism. As Oliver Impey has to promote the ever deepening trend towards the intermingling “a Collection of rarities” shipped from China by Jesuit missionar- observed, “people knew exactly what they wanted a ‘Chinese’ of the garden cultures of China and the rest of the world.”15 ies and bound for Paris.