The Boat People: a Novel by Sharon Bala (Doubleday, January 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALL the TIME in the WORLD a Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State University in Partial Fulfillm

ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD A written creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for 2 6 The Degree 201C -M333 V • X Master of Fine Arts In Creative Writing by Jane Marie McDermott San Francisco, California January 2016 Copyright by Jane Marie McDermott 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read All the Time in the World by Jane Marie McDermott, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Fine Arts: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Chanan Tigay \ Asst. Professor of Creative Writing ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD. Jane Marie McDermott San Francisco, California 2016 All the Time in the World is the story of gay young people coming to San Francisco in the 1970s and what happens to them in the course of thirty years. Additionally, the novel tells the stories of the people they meet along-the way - a lesbian mother, a World War II veteran, a drag queen - people who never considered that they even had a story to tell until they began to tell it. In the end, All the Time in the World documents a remarkable era in gay history and serves as a testament to the galvanizing effects of love and loss and the enduring power of friendship. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. Date ACKNOWLEDGMENT Thanks to everyone in the San Francisco State University MFA Creative Writing Program - you rock! I would particularly like to give shout out to Nona Caspers, Chanan Tigay, Toni Morosovich, Barbara Eastman, and Katherine Kwik. -

The Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Literary Journal

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal 2014 The yC borg Griffin: ap S eculative Literary Journal Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cyborg Part of the Fiction Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hollins University, "The yC borg Griffin: a Speculative Literary Journal" (2014). Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal. 3. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cyborg/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cyborg Griffin: a Speculative Fiction Literary Journal by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Volume IV 2014 The Cyborg Griffin A Speculative Fiction Literary Journal Hollins University ©2014 Tributes Editors Emily Catedral Grace Gorski Katharina Johnson Sarah Landauer Cynthia Romero Editing Staff Rachel Carleton AnneScott Draughon Kacee Eddinger Sheralee Fielder Katie Hall Hadley James Maura Lydon Michelle Mangano Laura Metter Savannah Seiler Jade Soisson-Thayer Taylor Walker Kara Wright Special Thanks to: Jeanne Larsen, Copperwing, Circuit Breaker, and Cyberbyte 2 Table of Malcontents Cover Design © Katie Hall Title Page Image © Taylor Hurley The Machine Princess Hadley James ......................................................................................... -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Most Borrowed Titles July 2005 – June 2006

MOST BORROWED TITLES JULY 2005 – JUNE 2006 Contents Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult & Children Combined) Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult) Most Borrowed Children’s Fiction Titles Most Borrowed Non-Fiction Titles (Adult) Most Borrowed Children’s Non-Fiction Titles Most Borrowed Classic Titles (Adult) Most Borrowed Classic Titles (Children) Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult & Children Combined) Author Title Publisher Year 1. Dan Brown The Da Vinci Code Corgi 2004 2. J K Rowling Harry Potter and the Half Blood Price Bloomsbury 2005 3. Maeve Binchy Nights of Rain and Stars Orion 2004 4. Dan Brown Digital Fortress Corgi 2004 5. Patricia Cornwell Trace Little, Brown 2004 6. James Patterson & Howard Roughan Honeymoon Headline 2005 7. James Patterson & Maxine Paetro 4th of July Headline 2005 8. John Grisham The Broker Century 2005 9. Josephine Cox The Journey HarperCollins 2005 10. Ian Rankin Fleshmarket Close Orion 2004 11. Josephine Cox Live the Dream HarperCollins 2004 12. James Patterson London Bridges Headline 2004 13. James Patterson Lifeguard Headline 2005 14. Dan Brown Angels and Demons Corgi 2003 15. Wilbur Smith Triumph of the Sun Macmillan 2005 16. Michael Connelly The Closers Orion 2005 17. James Patterson Mary, Mary Headline 2005 18. Jacqueline Wilson (illus Nick Sharratt) Clean Break Doubleday 2005 19. Kathy Reichs Cross Bones Heinemann 2005 20. Lee Child One Shot Bantam 2005 Most Borrowed Fiction Titles (Adult) Author Title Publisher Year 1. Dan Brown The Da Vinci Code Corgi 2004 2. Maeve Binchy Nights of Rain and Stars Orion 2004 3. Dan Brown Digital Fortress Corgi 2004 4. Patricia Cornwell Trace Little, Brown 2004 5. -

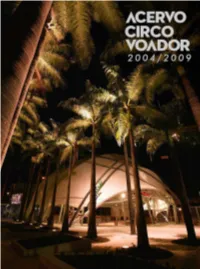

Acervo-Circovoador 2004-2009.Pdf

2004/2009 Primeira Edição Rio de Janeiro 2017 Roberta Sá 19/01/2009 Foto Lucíola Villela EXTRA / Agência O Globo Sumário 6 Circo Voador 8.Apresentação 21.Linha do Tempo/ Coleção de MiniDV 2004/2009 7 Apresentação Depois de mais de sete anos fechado, o Circo 13/07/2004 Voador foi reinaugurado no dia 22 de julho de Foto Michel Filho 2004. Os anos entre o fechamento e a reabertura Agência O Globo foram de muita militância cultural, política e judicial, num movimento que reuniu pessoas da classe artística e políticos comprometidos com as causas culturais. Vencedor de uma ação popular, o Circo Voador ganhou o direito de voltar ao funcionamento, e a prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro ‒ que havia demolido o arcabouço anterior ‒ foi obrigada a construir uma nova estrutura para a casa. Com uma nova arquitetura, futurista e mais atenta às questões acústicas inerentes a uma casa de shows, o Circo retomou as atividades no segundo semestre de 2004 e segue ininterruptamente oferecendo opções de diversão, alegria e formação artística ao público do Rio e a todos os amantes de música e arte em geral. 8 Circo Voador Apresentação Uma característica do Acervo Circo Voador pós-reabertura é que a grande maioria dos eventos tem registro filmado. Ao contrário do período 1982-1996, que conta com uma cobertura significativa mas relativamente pequena (menos de 15% dos shows filmados), após 2004 temos mais de 95% dos eventos registrados em vídeo. O formato do período que este catálogo abrange, que vai de 2004 a 2009, é a fita MiniDV, extremamente popular à época por sua relação custo-benefício e pela resolução de imagem sensivelmente melhor do que outros formatos profissionais e semiprofissionais. -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-1992 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (1992). Columbia Poetry Review. 5. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA POETRY REVIEW Columbia College/Chicago Spring 1992 Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the English Department of Columbia College, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60605. Submissions are encouraged and should be sent to the above address. Subscriptions and sample copies are available at $6.00 an issue. Copyright © I 992 by Columbia College. Grateful acknowledgement is made to Dr. Philip Klukoff, Chairman of the English Department; Dr. Sam Floyd, Academic Vice-President; Lya Rosenblum, D ean of Graduate Studies; Bert Gall, Administrative Vice President; and Mike Alexandroff, President of Columbia College. The cover photograph is by John Mulvany. Student Editors: John -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

Recent Issue-Driven Fiction for Young People

OOK WORLD B Boekwêreld • Ilizwe Leencwadi Recent issue-driven fi ction for young people Compiled by JOHANNA DE BEER Assistant Director: Selection and Acquisitions or an introduction to this list of realistic novels, written for older children and teenagers, that deal with issues that are there is, amazingly enough, somebody else out there who’s been Fexperienced by and of concern to this specifi c age group, I through exactly the same thing, it’s when you’re in your teenage turned to a very useful guide to teenage literature, The ultimate years. (Fiction can be hugely comforting for this, in a way that all teen book guide edited by Daniel Hahn and Leonie Flynn (Black, the self-help books in the world, for all their practical worthiness, 2006). This guide is a most useful resource for any teacher or simply cannot)… whatever your own experience it’s somehow librarian working with young people, and indeed young people enormously soothing to read a book that strikes a chord, that themselves, with annotations to over 700 titles suitable for makes you break off in the middle of a sentence and stare into the teenagers and suggestions for further reads if one has enjoyed a middle distance and nod and think: ‘Yes, that’s just how it feels’. specifi c title. Added extras include top ten lists culled from polling (p. 168.) teen readers themselves with the Harry Potter-series topping several Kevin Brooks is one author who does not shy away from the lists from the Book-that-changed-your-life to the Book-you-couldn’t grim reality and harsh challenges facing some young people. -

ED311449.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 449 CS 212 093 AUTHOR Baron, Dennis TITLE Declining Grammar--and Other Essays on the English Vocabulary. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1073-8 PUB DATE 89 NOTE :)31p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 10738-3020; $9.95 member, $12.95 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *English; Gr&mmar; Higher Education; *Language Attitudes; *Language Usage; *Lexicology; Linguistics; *Semantics; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Words ABSTRACT This book contains 25 essays about English words, and how they are defined, valued, and discussed. The book is divided into four sections. The first section, "Language Lore," examines some of the myths and misconceptions that affect attitudes toward language--and towards English in particular. The second section, "Language Usage," examines some specific questions of meaning and usage. Section 3, "Language Trends," examines some controversial r trends in English vocabulary, and some developments too new to have received comment before. The fourth section, "Language Politics," treats several aspects of linguistic politics, from special attempts to deal with the ethnic, religious, or sex-specific elements of vocabulary to the broader issues of language both as a reflection of the public consciousness and the U.S. Constitution and as a refuge for the most private forms of expression. (MS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY J. Maxwell TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." U S. -

University Photographs (SUJ-004): a Finding Aid Moakley Archive and Institute [email protected]

University Photographs (SUJ-004): A Finding Aid Moakley Archive and Institute www.suffolk.edu/moakley [email protected] University Photographs (SUJ-004): A Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Repository: Moakley Archive and Institute at Suffolk University, Boston, MA Location: Moakley Law Library, 5th Floor Collection Title: SUJ-004: University Photographs, 1906-present, n.d. Dates: 1906-present, n.d. Volume: 28.9 cu.ft. 145 boxes Preferred Citation: University Photographs. John Joseph Moakley Archive and Institute. Suffolk University. Boston, MA. Administrative Information Restrictions: Copyright restrictions apply to certain photographs; researcher is responsible for clearing copyright, image usage and paying all use fees to copyright holder. Related Collections and Resources: Several other series in the University Archives complement and add value to the photographs: • SUA-007.005 Commencement Programs and Invitations • SUA-012 Office of Public Affairs: Press releases, News clippings, Scrapbooks • SUG-001 Alumni and Advancement Publications • SUG-002 Academic Publications: Course Catalogs, Handbooks and Guides • SUG-003: University Newsletters • SUG-004: Histories of the University • SUH-001: Student Newspapers: Suffolk Journal, Dicta, Suffolk Evening Voice • SUH-002: Student Journals • SUH-003: Student Newsletters • SUH-005: Yearbooks: The Beacon and Lex • SUH-006: Student Magazines Scope and Content The photographs of Suffolk University document several facets of University history and life including events, people and places, student life and organizations and athletic events. The identity of the photographers may be professionals contracted by the University, students or staff, or unknown; the following is a list of photographers that have been identified in the collection: Michael Carroll, Duette Photographers, John Gillooly, Henry Photo, Herwig, Sandra Johnson, John C. -

Domestic Violence and Empire: Legacies of Conquest in Mexican American Writing Leigh Johnson

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-2-2011 Domestic Violence and Empire: Legacies of Conquest in Mexican American Writing Leigh Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Johnson, Leigh. "Domestic Violence and Empire: Legacies of Conquest in Mexican American Writing." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i ii DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND EMPIRE: LEGACIES OF CONQUEST IN MEXCIAN AMERICAN WRITING BY LEIGH JOHNSON B.A., International Affairs, Lewis & Clark College, 2001 M.A., English, Western Kentucky University, 2005 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy English The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2011 iii DEDICATION To the memory of Dr. Hector Torres and Stefania Grey. To my boys. For all the women, men, and children who have been silenced by domestic violence. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have contributed to my finishing this project, and I would be remiss to not thank them for their investment in my scholarship and person. First, thank you to my advisor, mentor, and committee chair, Dr. Jesse Alemán. I really could not have completed the project without your encouragement, faith, and thoughtful comments. I owe you many growlers.