Taran's Wheel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 1851 Census for Glenmuick, Tullich & Glengairn

Transcriptions of Records for the name McHardy from the 1851 Census for the Parish of Glenmuick, Tullich & Glengairn Transcribed by Sandra DeMartino, Jan 2003 Web address: http://www.geocities.com/mchardyofordachoy Email address: [email protected] Microfilmed by the Genealogical Society Salt Lake City, Utah, at Edinburgh Scotland Date filmed: 17 Jul 1982 Film Number: 1042117 County of Aberdeen Parish: Glenmuick, Tullich & Glengairn Title of Record: Census Returns Volume/s: 201 Years Included 1851 1851 Census Glengairn and Glenmuick ED 1 From a point on the River Dee opposite to Deecastle, in a straight line to the River Tanner near Elnich, from thence along the north bank of said river Tanner to Corrynach and from thence to the bridge of Muick, then along the south bank of the Dee to Dee castle. The District is about 5 ½ miles long, 5 miles in breadth, is mountainous and the Houses are widely detached. Name of Street, Place, or Name & Surname of Relation to Condition Age Rank, Profession or Where Born Road, and Name or No. each Person who Head of M F Occupation of House abode in the house, Family on the Night of the 30th March, 1851 No. of Householders Schedule 25 Ballindory Jane Bowman Head U 61 Pauper (Ag. Lab) Aberdeenshire Glenmuick Ann Do Sister U 59 Stocking Knitter Do Do Margaret Do Do U 57 Pauper (Ag. Lab) Do Do 1851 Census – Glengairn and Glenmuick 2 ED 2 From the Bridge of Muick along the South bank of the River to Loch Muick, from thence to Corryurach, and then to the Bridge of Muick. -

Extended Phase 1 Habitat Survey

Cairngorms National Park Local Development Plan 199 Main Issues Report - Background Evidence 5. Site Analysis 200 Cairngorms National Park Local Development Plan 201 Main Issues Report - Background Evidence 5. Site Analysis 202 Cairngorms National Park Local Development Plan ) New Flora of the British IslesSecond Ed Epilobium angustifolium Senecio jacobaea), Galium aparine Rumex obtusifoliusCirsium spp.) Ulmus glabra Quercus spp 203 Main Issues Report - Background Evidence 5. Site Analysis Fig Handbook for Phase 1 habitat survey − a technique for environmental audit. New Flora of the British Isles 204 Cairngorms National Park Local Development Plan 205 Main Issues Report - Background Evidence 5. Site Analysis 206 Cairngorms National Park Local Development Plan 207 Main Issues Report - Background Evidence 5. Site Analysis -

Excavations at Craigievar Castle, Aberdeenshire Moira K Greig* with Contributions by Colvin Greig, Bill Lindsay, Stewart Thain & Gordon Williamson

Proc Antiqc So Scot,(1993)3 12 , 381-93, fiche 2:B1-C4 Excavations at Craigievar Castle, Aberdeenshire Moira K Greig* with contributions by Colvin Greig, Bill Lindsay, Stewart Thain & Gordon Williamson ABSTRACT In the summer of 1990 the National Trust for Scotland funded an excavation to increase their knowledge of Craigievar Castle. This excavation revealed the remains of the east wall and part of the south wall of the original barmkin, along with two contemporary stone drains and a few post-holes. The excavation also recovered coins, pottery and glass. INTRODUCTION Aberdeenshire, now part of Grampian Region, is well known for its great castles. Of the later castles, built in the 17th century, many carried on the tradition of building a contiguous courtyard, or barmkin, although the defensive need for its surrounding wall was rarely required by that time. Today most of these castles have lost their barmkins or have only fragmentary remains, and little is known about their design (for the Lowlands, see Good & Tabraham 1988). However t Craigievaa , r Castlee paristh f n Leochel-Cushnii o h, J (N e 56670748), there exist almosn sa t complete stretc barmkif ho n wall. No contemporary records are known to exist that describe the interior of the courtyard t Craigievara , althoug assumn ca e ehon that there were stable byresd san brewerya , smithya , , and other necessary buildings. There are, however, within the castle, two 18th-century plans which, though differing in some of the structural details that they depict, do show definitive evidence of a barmkin wall enclosing a courtyard with internal buildings. -

Lads of Tarland.Qxp

The Lads of Tarland jig Alexander Walker G G G D ¢ # 6 œ œ j & 8 œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ G G œ CDœ G œ œ œ œ œ œ . œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ . œ œ œ œ œ œ œ G G G Amin D œ œ œ œ ¢ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ . J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ J 1. G G CD G œ œ œ œ ¢ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ . œ J œ œ œ œ . 2. GD CG CD Gœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ J œ œ œ œ œ œ œ LADS OF TARLAND, THE. Walker: A Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Marches, &c., 1866; No. 185, pg. 63. œ œ œ Scottish, Jig. G Major, AABB'. i. Dan Hughie MacEachern, tape, c.1970, reissued to CD. ii. Andrea Beaton, CD, c.2004 Popularized by Buddy MacMaster at dances. Tarland is a village some 10 miles from Castle Newe. It has a colourful history according to the following account (From ‘Scottish Fiddle Club of Colorado Some Perspectives on Scottish Fiddling’) relating to the eighteenth century: "An almost invariable accompaniment of certain of the fairs was the occurrence of party fights, or personal encounters between rustic athletes fond of testing their physical prowess. These encounters, which ordinarily took place about the close of the fair, were sufficiently brutal in character, the combatants often mercilessly belabouring each other with cudgels. -

Royal Deeside Lodge Region: Highlands Sleeps: 10 - 20

Royal Deeside Lodge Region: Highlands Sleeps: 10 - 20 Overview Royal Deeside Lodge holds a wonderful rural position, situated just five minutes from the village of Aboyne on the edge of the beautiful Highlands. The lodge is perfect for large families or groups of friends who are looking for a tranquil escape where they can really enjoy the unparalleled beauty of Aberdeenshire! The lodge can comfortably accommodate up to twenty guests across ten, luxury bedrooms, each of the bedrooms boast their own en-suite bathrooms making it a practical choice for a group of couples. On the ground floor, is the main entertaining space which comprises of the drawing room and dining room. The beautifully appointed dining room is a fantastic space for the whole family to gather and enjoy a delicious meal prepared by the in-house chef after working up an appetite exploring the surrounding countryside. Also on this level, are the first five of the individually-designed super-king size bedrooms, two of which benefit from disabled access. Upstairs, on the first floor are four further super-king bedrooms and a smaller twin, which is perfect for the children. The outside space is vast and therefore makes the ultimate choice for fans of the great outdoors. The children will love the opportunity to run freely and explore the wild landscape and family doggies are welcome to come too! For those keen on fishing, the River Dee is just a short stroll away, excellent for salmon and sea trout. If you are looking for a relaxing stay in the country with a touch of luxury, -

1696 Hearth Tax, Aberdeenshire Residents

1696 Poll Tax List for the North East of Scotland In the latter part of the 17th century, the Scottish economy was in poor shape. Among several unpopular taxes introduced during this period was the Poll Tax that imposed a tax on every person over 16 (14?) years of age and not a beggar. The list of persons in Aberdeenshire is supposedly the only complete county list in existence, and enumerates some 30,000 persons, although less than 100 of these are Brebner/Bremner individuals. I have transcribed the Brebner/Bremner and all variant spellings from the indexes published by the late Archie Strath Maxwell and found in the main public library in Aberdeen. The Aberdeen and NE Scotland Family History Society (ANESFHS) has a series of full transcriptions of many of the Aberdeenshire parishes available for purchase, and I would recommend these to anyone who has traced their ancestors back to this early period. Many of the 1696 parishes had different names and boundaries than their 19th century counterparts, although farm names are often continued through the centuries. In looking through the Brebner/Bremner entries for Aberdeenshire, I found it most interesting that some parishes in which the families were well represented in the 18th and 19th centuries had no entries in 1696. This suggests that the founding members of those families came from other parts of Aberdeenshire, or indeed from other parts of Scotland. Trying to match individuals in this population poll with corresponding births or christenings is hampered by the lack of Old Parish Registers for many of the under-mentioned parishes during that early time. -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Alford Designation Record

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Alford The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Summary Report Contents Name Inventory Boundary Alternative Name(s) Historical Background to the Battle Date of Battle Events and Participants Local Authority Battlefield Landscape NGR Centred Archaeological and Physical Date of Addition to Inventory Remains and Potential Date of Last Update Cultural Association Overview and Statement of Select Bibliography Significance Inventory of Historic Battlefields ALFORD Alternative Names: None 2 July 1645 Local Authority: Aberdeenshire NGR centred: NJ 567 162 Date of Addition to Inventory: 21 March 2011 Date of last update: 14 December 2012 Overview and Statement of Significance The Battle of Alford is significant as one of Montrose’s most notable victories in his campaign within Scotland on behalf of Charles I. -

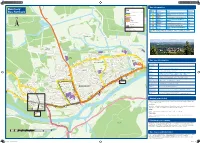

Banchory Bus Network

Bus Information A Banchory 9 80 Key Service Bus Network Bus services operating around Banchory Number Operator Route Operation 105 201 Stagecoach Aberdeen-Banchory-Aboyne-Ballater- Bluebird Braemar M-F, S, Su 201.202.203 202 Stagecoach 204 Bluebird Aberdeen-Banchory-Lumphanan/Aboyne M-F, S, Su Brathens VH5PM VH3 203 Stagecoach Aberdeen-Banchory/Aboyne/Ballater/ Wood Bluebird Braemar M-F VH5PM 204 Stagecoach Direction of travel Bluebird Aberdeen-Banchory-Strachan M-F ©P1ndar Bus stop VH3 Deeside Tarland-Aboyne-Finzean-Banchory Thu Building Drumshalloch Contains Ordnance Survey data VH5 Aboyne-Lumphanan-Tarland/Banchory © Crown copyright 2016 Deeside Circular F A980 Wood Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative www.pindarcreative.co.uk 01296 390100 Key: M-F - Monday to Friday Thu - Thursday F - Friday S - Saturday Su - Sunday Locton of Leys Upper Locton Wood VH5PM Upper Banchory Woodend Barn Locton Business Arts Centre Centre Biomass Road ’Bennie Energy Burn O Centre Business h ©P1ndar rc Tree C Centre a re L s ce t ©P1ndar n Pine Tree ry Eas H t ho Business il A Road ill of Banc l o 9 ©P1ndar H Centre f 8 B 0 ©P1ndar 201.202.203 ancho Raemoir 203 Pine Tree 201.202.203 Larch Tree Road ry Garden Centre d ©P1ndar E Crescent a a 203 o Hill of ©P1ndar s Oak Tree ©P1ndar R t y West e Banchory Avenue Hill of Banchor Larch Tree e ©P1ndar r Burn of Raemoir ©P1ndar Crescent Pine T Hill of Bus fare information Garden Sycamore ©P1ndar Bennie ©P1ndar Banchory ©P1ndar Centre Place ©P1ndar Sycamore Oak Tree Hill of Banchory Place Tesco Avenue ©P1ndar 203 est Tesco W d ry a Holly Tree ho 201.202 o VH5PM anc e R Ticket type Road f B Tre VH5PM ©P1ndar o aird’s W ll ne 201.202.203 C y i h Pi nd H t u ent VH5PM o resc Tesco S C ©P1ndar ©P1ndar stnut y he Single For a one-way journey, available on the bus. -

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

Spring Newsletter 2005

Aberdeen Telephones Hillwalking Club SPRING NEWSLETTER 2005 CHAIRMAN’S CHAT trend will likely continue and we applied the Spring is in the air, with snowdrops and crocuses maximum fare of £12 quite a few times in 2004, over and daffodils in full bloom. As we emerge the AGM increased the maximum from £12 to £14. from dark winter days to lengthening daylight and warmer weather, the new season of walks planned Gratuities for both Braemar Mountain Rescue some time ago turns into the reality of walking in Team and Mountain Rescue Association of the countryside and climbing hills. Scotland were increased from £50 to £75. Our affiliations to North East Mountain Trust and Our walks were well attended during winter, and Ramblers’ Association were continued. we look forward to a new, exciting program. Even at this early stage of the year, we have had some The £10 annual membership fee remains good days such as the coastal walk from Bullers of unchanged. There was little support for reducing Buchan to Collieston, as well as not so good days - it to the £5 rate of a few years ago. the Mortlich-Craiglich walk was wet and misty with low cloud most of the day. The following were elected: - President ......................................................... Frank Kelly I am encouraged to see new members on our Vice President ....................................... Jim Henderson outings, and we extend a warm welcome. We look Secretary ................................................ Heather Eddie forward to getting to know you better during the Treasurer .............................................. Sally Henderson year, and hope you enjoy the Club. Booking Secretary ...................................... Alex Joiner Committee Members .... -

Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies

1 From mountain to sea Aberdeenshirep Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies December 2017 2 | Contents 1 BENEFITS 3 2 CHILDCARE AND RESPITE 23 3 COMMUNITY ACTION 43 4 COMPLAINTS 50 5 EDUCATION AND LEARNING 63 6 Careers 81 7 FINANCIAL HELP 83 8 GENERAL SUPPORT 103 9 HEALTH 180 10 HOLIDAYS 194 11 HOUSING 202 12 LEGAL ASSISTANCE AND ADVICE 218 13 NATIONAL AND LOCAL SUPPORT GROUPS (SPECIFIC CONDITIONS) 223 14 SOCIAL AND LEISURE OPPORTUNITIES 405 15 SOCIAL WORK 453 16 TRANSPORT 458 SEARCH INSTRUCTIONS 1. Right click on the document and select the word ‘Find’ (using a left click) 2. A dialogue box will appear at the top right hand side of the page 3. Enter the search word to the dialogue box and press the return key 4. The first reference will be highlighted for you to select 5. If the first reference is not required, return to the dialogue box and click below it on ‘Next’ to move through the document, or ‘previous’ to return 1 BENEFITS 1.1 Advice for Scotland (Citizens Advice Bureau) Information on benefits and tax credits for different groups of people including: Unemployed, sick or disabled people; help with council tax and housing costs; national insurance; payment of benefits; problems with benefits. http://www.adviceguide.org.uk 1.2 Attendance Allowance Eligibility You can get Attendance Allowance if you’re 65 or over and the following apply: you have a physical disability (including sensory disability, e.g. blindness), a mental disability (including learning difficulties), or both your disability is severe enough for you to need help caring for yourself or someone to supervise you, for your own or someone else’s safety Use the benefits adviser online to check your eligibility.