Evidence That Blue Petrel, Halobaena Caerulea, Fledglings Can Detect And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdlife Australia Rarities Committee Unusual Record Report Form

BirdLife Australia Rarities Committee Unusual Record Report Form This form is intended to aid observers in the preparation of a submission for a major rarity in Australia. (It is not a mandatory requirement) Please complete all sections ensuring that you attach all relevant information including any digital images (email to [email protected] or [email protected]). Submissions to BARC should be submitted electronically wherever possible. Full Name: Rob Morris Office Use Address: Phone No: Robert P. Morris, Email: Full Name: Andrew Sutherland (first noticed the second bird) Address: Phone No: Email: Species Name: Broad-billed Prion Scientific Name: Pachyptila vittata Date(s) and time(s) of observation: 11 August 2019 First individual photographed at 12.22 – last bird photographed at 13.11. How long did you watch the bird(s)? c30+ minutes – multiple sightings of 2 birds (possibly 3) and then an additional sighting of 1 bird 20 minutes later whilst travelling, flying past and photographed. First and last date of occurrence: 11 August 2019 Distance to bird: Down to approximately 20-30 m Site Location: SE Tasmania. Approximately 42°50'36.30"S 148°24'46.23"E 22NM ENE of Pirates Bay, Eaglehawk Neck. We went north in an attempt to seek lighter winds and less swell and avoid heading straight into the strong SE winds and southerly swell. Habitat (describe habitat in which the bird was seen): Continental slope waters at a depth of approximately 260 fathoms. Sighting conditions (weather, visibility, light conditions etc.): Weather: Both days were mostly cloudy with occasional periods of bright sunshine. -

DIET and ASPECTS of FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING at SOUTH GEORGIA by P.A

DIET AND ASPECTS OF FAIRY PRIONS BREEDING AT SOUTH GEORGIA By P.A. PRINCE AND P.G. COPESTAKE ABSTRACT A subantarctic population of the Fairy Prion (Pachyprzla turtur) was studied at South Georgia in 1982-83. Full measurements of breeding birds are given, together with details of breeding habitat, the timing of the main breeding cycle events, and chick growth (weight and wing, culmen and tarsus length). Regurgitated food samples showed the diet to be mainly Crustacea (96% by weight), fish and squid comprising the rest. Of crustaceans, Antarctic krill made up 38% of items and 80% by weight. Copepods (four species, mostly Rhincalanus gigas) made up 39% of items but only 4% by weight; amphipods [three species, principally Themisto gaudichaudii made up 22% of items and 16% by weight. Diet and frequency of chick feeding are compared with those of Antarctic Prions and Blue Petrels at the same site; Fairy Prions are essentially intermediate. INTRODUCTION The Fairy Prion (Pachyptila turtur) is one of six members of a genus confined to the temperate and subantarctic regions of the Southern Hemisphere. With the Fulmar Prion (P. crassirostris), it forms the subgenus Pseudoprion. Its main area of breeding distribution is between the Antarctic Polar Front and the Subtropical Convergence. It is widespread in the New Zealand region, from the north of the North Island south to the Antipodes Islands and Macquarie Island, where only about 40 pairs survive (Brothers 1984). Although widespread in the Indian Ocean at the Prince Edward, Crozet and Kerguelen Islands, in the South Atlantic Ocean it is known to breed only on Beauchene Island (Falkland Islands) (Strange 1968, Smith & Prince 1985) and South Georgia (Prince & Croxall 1983). -

Spatial Segregation of Prions and Blue Petrels Is Explained by Differences in Preferred Sea Surface Temper

Animal behaviour Cool, cold or colder? Spatial segregation rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org of prions and blue petrels is explained by differences in preferred sea surface temperatures Research 1 2 2 2 Cite this article: Quillfeldt P, Cherel Y, Delord Petra Quillfeldt , Yves Cherel , Karine Delord and Henri Weimerkirch K, Weimerkirch H. 2015 Cool, cold or colder? 1Department of Animal Ecology and Systematics, Justus-Liebig-Universita¨t Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany Spatial segregation of prions and blue petrels 2Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chize´, UMR 7372 CNRS-Universite´ de La Rochelle, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France is explained by differences in preferred sea surface temperatures. Biol. Lett. 11: 20141090. The Southern Ocean provides one of the largest environmental gradients on http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.1090 Earth that lacks geographical barriers, and small but highly mobile petrels living there may offer fine models of evolution of diversity along environmental gradients. Using geolocation devices, we investigated the winter distribution of closely related petrel species breeding sympatrically in the southern Indian Received: 31 December 2014 Ocean, and applied ecological niche models to compare environmental con- ditions in the habitat used. We show that thin-billed prions (Pachyptila Accepted: 27 March 2015 belcheri), Antarctic prions (Pachyptila desolata) and blue petrels (Halobaena caerulea) from the Kerguelen archipelago in the southern Indian Ocean segre- gate latitudinally, sea surface temperature being the most important variable separating the distribution of the species. Antarctic prions spent the winter Subject Areas: north of the Polar Front in temperate waters, whereas blue petrels were ecology, behaviour found south of the Polar Front in Antarctic waters. -

Master Wildlife List-Peninsula

Antarctic Peninsula Expedition Wildlife List Date Family Species Twitcher List 8-Mar 9-Mar 10-Mar 11-Mar 12-Mar 13-Mar 14-Mar 15-Mar 16-Mar 17-Mar Adelie X X Chinstrap X X X X X X Emperor Penguins Gentoo X X X X X X X Macaroni X X Magellanic X X Unidentifed X X X Black-browed X X X X X Grey-headed X X X X Light-mantled Sooty X X Albatross Northern Royal X X X Southern Royal X X X Wandering X X X Northern X X X X Southern X X X X X X X Giant Petrel Southern (white morph) X X X Unidentified Soft-plumaged Petrel X X X X Gadfly Petrels Soft-plumaged Petrel (Dark) X X Antarctic Petrel Cape Petrel X X X X X X Snow Petrel ? ? Petrels Southern Fulmar X X X X White-chinned Petrel X X X Grey Petrel Great Shearwater X X Shearwaters Sooty Shearwater X X X X Blue Petrel Antarctic Prion X X X X BIRDS Blue Petrels & Prions Fairy Prion Slender-billed Prion X X Unidentified Black-bellied X X X X Grey-backed Storm-petrels Wilson’s X X X X X X X X Unidentified Common Diving-petrels Magellanic Unidentified X X X Antarctic Shag X X X X X X Shags Imperial Shag X X Rock Shag X X Chilean Skua X X South Polar Skua X X X X X X Skuas Subantarctic Skua X X X X X X Unidentified X X Brown-hooded Gull X X Gulls Dolphin Gull X X Kelp Gull X X X X X X X Antarctic X X X X X Terns Arctic South American Blk-crowned Night Heron Blackish Oystercatcher Shorebirds Magellanic Oystercatcher Magellanic Snipe Pale-faced Sheathbill X X X X Other Arnoux's Beaked Blue Cuvier's Beaked Fin Whale Hector's Beaked Humpback X X X Long-finned Pilot Whales Minke X X X X Sei X X X X Southern Bottlenose Southern Right Sperm Beaked (sp.) X X MAMMALS Unidentified Dusky Hourglass X X Orca (Killer Whale) X X Dolphins Peale’s X X Other Unidentified Crabeater X X X X X Leopard X X X X Phocids Southern Elephant X X X Weddell X X X X Antarctic Fur Seal X X X X X Otariids South American Fur Seal South American Sealion OTHER Chilean swallow X X Salp X 8-Mar 9-Mar 10-Mar 11-Mar 12-Mar 13-Mar 14-Mar 15-Mar 16-Mar 17-Mar Twitcher List Date www.oneoceanexpedi,ons.com. -

Densities of Antarctic Seabirds at Sea and the Presence of the Krill Eupha Usia Superba

DENSITIES OF ANTARCTIC SEABIRDS AT SEA AND THE PRESENCE OF THE KRILL EUPHA USIA SUPERBA BRYAN S. OBST Departmentof Biology,University of California,Los Angeles, California 90024 USA ABSTRACT.--Theantarctic krill Euphausiasuperba forms abundant,well-organized schools in the watersoff the AntarcticPeninsula. Mean avian densityis 2.6 timesgreater in waters where krill schoolsare present than in waters without krill schools.Seabird density is a good predictorof the presenceof krill. Seabirddensity did not correlatewith krill density or krill schooldepth. Disoriented krill routinely were observedswimming near the surface above submergedschools, providing potential prey for surface-feedingbirds. Responsesof seabird speciesto the distribution of krill schoolsvaried. The small to me- dium-sizeprocellariiform species were the best indicatorsof krill schools;large procellari- iforms and coastalspecies were poor indicators.Pygoscelis penguins occurredat high den- sitiesonly in the presenceof krill schools.These responses are consistentwith the constraints imposedby the metabolicrequirements and reproductivestrategies of eachof thesegroups. Krill schoolswere detectednear the seasurface throughout the day. Correlationsbetween seabirddensity and the presenceof krill during daylight hourssuggest that diurnal foraging is important to the seabirdsof this region. Received19 December1983, accepted4 December 1984. RELATIVELY little is known about the factors birds depend on directly or indirectly for food influencing the distribution of seabirdsin the (Haury et al. 1978). These observationssuggest marine habitat. The past decade has produced that relatively small-scalephenomena, such as a number of studiesattempting to correlatepat- local concentrationsof prey, may be of major terns of avian abundance and distribution with importance in determining the patterns of sea- physical featuresof the oceansuch as currents bird distribution within the broad limits set by and convergences,water masses,and temper- featuresof the physical ocean. -

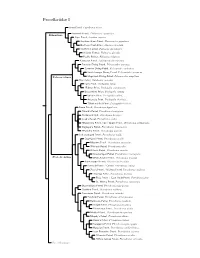

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Niche Switching and Leapfrog Foraging: Movement Ecology of Sympatric Petrels During the Early Breeding Season

Quillfeldt et al. Movement Ecology (2020) 8:23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-020-00212-y RESEARCH Open Access Niche switching and leapfrog foraging: movement ecology of sympatric petrels during the early breeding season Petra Quillfeldt1* , Henri Weimerskirch2, Karine Delord2 and Yves Cherel2 Abstract Background: The timing of events in the early part of the breeding season is crucially important for successful reproduction. Long-lived animals that migrate large distances independently of each other meet at the breeding sites to re-establish their pair bonds and coordinate their breeding duties with their partners. Methods: Using miniature light-geolocation and immersion data together with blood stable isotopes, we studied the early breeding season in Thin-billed prions Pachyptila belcheri, Antarctic prions P. desolata and Blue petrels Halobaena caerulea breeding at Kerguelen Islands in the Indian Ocean. These three species exhibit differences in their winter habitat and timing of migration, moult and breeding. We hypothesised that these differences would influence their behaviour during the early breeding season. Results: In line with our hypothesis, we found clear differences not only in the timing of colony attendance, but also in the time budgets while at sea and in habitat use. Both early breeding Blue petrels and late breeding Antarctic prions spent about 8 h per day in flight and 15 h foraging. In comparison, Thin-billed prions, which breed in mid- summer, spent less time (5 h daily) in flight and more time (18 h daily) foraging, thus maximizing the time spent foraging during the longest daylight days of the year. While the ecological habitat parameters (sea temperature, wind, productivity) of Thin-billed prions and Blue petrels were relatively stable throughout the year, Antarctic prions showed clear niche switching, caused by leapfrogging between the northernmost winter distribution to the southernmost distribution during the early breeding season. -

Does Genetic Structure Reflect Differences in Non-Breeding Movements? a Case Study in Small, Highly Mobile Seabirds

Quillfeldt et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:160 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-1008-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Does genetic structure reflect differences in non-breeding movements? A case study in small, highly mobile seabirds Petra Quillfeldt1* , Yoshan Moodley2, Henri Weimerskirch3, Yves Cherel3, Karine Delord3, Richard A. Phillips4, Joan Navarro5, Luciano Calderón1 and Juan F. Masello1 Abstract Background: In seabirds, the extent of population genetic and phylogeographic structure varies extensively among species. Genetic structure is lacking in some species, but present in others despite the absence of obvious physical barriers (landmarks), suggesting that other mechanisms restrict gene flow. It has been proposed that the extent of genetic structure in seabirds is best explained by relative overlap in non-breeding distributions of birds from different populations. We used results from the analysis of microsatellite DNA variation and geolocation (tracking) data to test this hypothesis. We studied three small (130–200 g), very abundant, zooplanktivorous petrels (Procellariiformes, Aves), each sampled at two breeding populations that were widely separated (Atlantic and Indian Ocean sectors of the Southern Ocean) but differed in the degree of overlap in non-breeding distributions; the wintering areas of the two Antarctic prion (Pachyptila desolata) populations are separated by over 5000 km, whereas those of the blue petrels (Halobaena caerulea) and thin-billed prions (P. belcheri) show considerable overlap. Therefore, we expected the breeding populations of blue petrels and thin-billed prions to show high connectivity despite their geographical distance, and those of Antarctic prions to be genetically differentiated. Results: Microsatellite (at 18 loci) and cytochrome b sequence data suggested a lack of genetic structure in all three species. -

Falkland Islands Species List

Falkland Islands Species List Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 BIRDS* 2 DUCKS, GEESE, & WATERFOWL Anseriformes - Anatidae 3 Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus 4 Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba 5 Upland Goose Chloephaga picta 6 Kelp Goose Chloephaga hybrida 7 Ruddy-headed Goose Chloephaga rubidiceps 8 Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus 9 Falkland Steamer-Duck Tachyeres brachypterus 10 Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides 11 Chiloe Wigeon Anas sibilatrix 12 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 13 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera 14 Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica 15 Silver Teal Anas versicolor 16 Yellow-billed Teal Anas flavirostris 17 GREBES Podicipediformes - Podicipedidae 18 White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland 19 Silvery Grebe Podiceps occipitalis 20 PENGUINS Sphenisciformes - Spheniscidae 21 King Penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus 22 Gentoo Penguin Pygoscelis papua Cheesemans' Ecology Safaris Species List Updated: April 2017 Page 1 of 11 Day Common Name Scientific Name x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 23 Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus 24 Macaroni Penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus 25 Southern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome 26 ALBATROSSES Procellariiformes - Diomedeidae 27 Gray-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma 28 Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris 29 Royal Albatross (Southern) Diomedea epomophora epomophora 30 Royal Albatross (Northern) Diomedea epomophora sanfordi 31 Wandering Albatross (Snowy) Diomedea exulans exulans 32 Wandering -

Detecting Cryptic Burrowing Petrels Recovery Post Eradication in a Remote Landscape

Detecting cryptic burrowing petrels recovery post eradication in a remote landscape By Julie McInnes In collaboration with: Jez Bird, Bruce Deagle, Rachael Alderman and Justine Shaw National Environmental Science Programme 4.2.3.4 August 2019 Cite this publication as: McInnes, J. with Bird, J., Deagle, B., Alderman, R, Shaw, J. 2019. Detecting cryptic burrowing petrels recovery post eradication in a remote landscape. NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub Project 4.2.3.4 report, Brisbane. Cover image: White-headed petrel. This is one of several burrowing petrel species that are recovering on Macquarie Island following invasive species eradication. Image:Jez Bird. 2 Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Methods .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Sample collection ................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Primer design .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Standardizing Microsatellite Panels for Individual Identification of Seabirds' Snow Petrel Pagodroma Nivea and Wilson's Stor

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/221861; this version posted November 18, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Standardizing microsatellite panels for individual identification of seabirds’ Snow Petrel Pagodroma nivea and Wilson’s Storm Petrel Oceanites oceanicus in Antarctica Running head: Individual identification of two Antarctic seabird species Anant Pande*, Nidhi Rawat*, Kuppusamy Sivakumar, Sambandan Sathyakumar, Vinod B. Mathur, Samrat Mondol# Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India 248001 *equal contribution # Corresponding author: Samrat Mondol, Assistant Professor, Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India 248001. Email: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/221861; this version posted November 18, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. ABSTRACT Seabirds are known to be important indicators of marine ecosystems health. Procellariiformes are one of the most abundant seabird species distributed from warm tropical to cold temperate regions including Antarctica. With few long-term studies on breeding seabirds at the Antarctic continent, crucial biological parameters such as genetic variation, population genetic structure and past population demography is lacking for most of the commonly occurring species. Under the ‘Biology and Environmental Sciences’ component of the Indian Antarctic programme, long-term monitoring of Antarctic biodiversity is being conducted. -

American Ornithological Union (AOU) Bird Species List 1

American Ornithological Union (AOU) Bird Species List 1 Alpha Alpha Species Code Species Code Western Grebe WEGR Glaucous-winged Gull GWGU Clark's Grebe CLGR Hybrid Gull HYGU Red-necked Grebe RNGR Great Black-backed Gull GBBG Horned Grebe HOGR Slaty-backed Gull SBGU Eared Grebe EAGR Western Gull WEGU Least Grebe LEGR Yellow-footed Gull YFGU Pied-billed Grebe PBGR Lesser Black-backed Gull LBBG Common Loon COLO Herring Gull HERG Yellow-billed Loon YBLO California Gull CAGU Arctic Loon ARLO Unidentified Gull UNGU Pacific Loon PALO Ring-billed Gull RBGU Red-throated Loon RTLO Band-tailed Gull BTGU Tufted Puffin TUPU Mew Gull MEGU Atlantic Puffin ATPU Black-headed Gull BHGU Horned Puffin HOPU Heermann's Gull HEEG Rhinoceros Auklet RHAU Laughing Gull LAGU Cassin's Auklet CAAU Franklin's Gull FRGU Parakeet Auklet PAAU Bonaparte's Gull BOGU Crested Auklet CRAU Little Gull LIGU Whiskered Auklet WHAU Ross' Gull ROGU Least Auklet LEAU Sabine's Gull SAGU Ancient Murrelet ANMU Gull-billed Tern GBTE Marbled Murrelet MAMU Caspian Tern CATE Kittlitz's Murrelet KIMU Royal Tern ROYT Xantus' Murrelet XAMU Crested Tern CRTE Craveri's Murrelet CRMU Elegant Tern ELTE Black Guillemot BLGU Sandwich Tern SATE Pigeon Guillemot PIGU Cayenne Tern CAYT Common Murre COMU Forster's Tern FOTE Thick-billed Murre TBMU Common Tern COTE Razorbill RAZO Arctic Tern ARTE Dovekie DOVE Roseate Tern ROST Great Skua GRSK Aleutian Tern ALTE South Polar Skua SPSK Black-naped Tern BNTE Pomarine Jaeger POJA Least Tern LETE Parasitic Jaeger PAJA Sooty Tern SOTE Long-tailed Jaeger LTJA