Chapter Four the Jesuit Heritage in Eastern Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of the Heights Thomas H. O'connor

THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian to An e-book published by Linden Lane Press at Boston College. THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian Linden Lane Press at Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts Linden Lane Press at Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue 3 Lake Street Building Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02467 617–552–4820 www.bc.edu/lindenlanepress Copyright © 2011 by The Trustees of Boston College All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval) without the permission of the publisher. Printed in the USA ii contents preface d Thomas H. O’Connor v Dancing Under the Towers 22 Dante Revisited 23 a “Dean’s List” 23 AHANA 1 Devlin Hall 24 Alpha Sigma Nu 2 Donovan, Charles F., S.J. 25 Alumni 2 Dustbowl 25 AMDG 3 Archangel Michael 4 e Architects 4 Eagle 27 Equestrian Club 28 b Bands 5 f Bapst Library 6 Faith on Campus 29 Beanpot Tournament 7 Fine Arts 30 Bells of Gasson 7 Flutie, Doug 31 Black Talent Program 8 Flying Club 31 Boston “College” 9 Ford Tower 32 Boston College at War 9 Fulbright Awards 32 Boston College Club 10 Fulton Debating Society 33 Bourneuf House 11 Fundraising 33 Brighton Campus 11 Bronze Eagle 12 g Burns Library 13 Gasson Hall 35 Goldfish Craze 36 c Cadets 14 h Candlemas Lectures 15 Hancock House 37 Carney, Andrew 15 Heartbreak Hill 38 Cavanaugh, Frank 16 The Heights 38 Charter 17 Hockey 39 Chuckin’ Charlie 17 Houston Awards 40 Church in the 21st Century 18 Humanities Series 40 Class of 1913 18 Cocoanut Grove 19 i Commencement, First 20 Ignatius of Loyola 41 Conte Forum 20 Intown College 42 Cross & Crown 21 Irish Hall of Fame 43 iii contents Irish Room 43 r Irish Studies 44 Ratio Studiorum 62 RecPlex 63 k Red Cross Club 63 Kennedy, John Fitzgerald 45 Reservoir Land 63 Retired Faculty Association 64 l Labyrinth 46 s Law School 47 Saints in Marble 65 Lawrence Farm 47 Seal of Boston College 66 Linden Lane 48 Shaw, Joseph Coolidge, S.J. -

Reaching for Freedom: Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 Reaching for Freedom: Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts Emily V. Blanck College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blanck, Emily V., "Reaching for Freedom: Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626189. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-yxr6-3471 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACHING FOR FREEDOM Black Resistance and the Roots of a Gendered African-American Culture in Late Eighteenth Century Massachusetts A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts b y Emily V. Blanck 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Emily Blanck Approved, April 1998 Leisa Mever (3Lu (Aj/K) Kimb^ley Phillips ^ KlU MaU ________________ Ronald Schechter ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As is the case in every such project, this thesis greatly benefitted from the aid of others. -

Archbishop John J. Williams

Record Group I.06.01 John Joseph Williams Papers, 1852-1907 Introduction & Index Archives, Archdiocese of Boston Introduction Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Content List (A-Z) Subject Index Introduction The John Joseph Williams papers held by the Archives of the Archdiocese of Boston span the years 1852-1907. The collection consists of original letters and documents from the year that Williams was assigned to what was to become St. Joseph’s parish in the West End of Boston until his death 55 years later. The papers number approximately 815 items and are contained in 282 folders arranged alphabetically by correspondent in five manuscript boxes. It is probable that the Williams papers were first put into some kind of order in the Archives in the 1930s when Fathers Robert h. Lord, John E. Sexton, and Edward T. Harrington were researching and writing their History of the Archdiocese of Boston, 1604-1943. At this time the original manuscripts held by the Archdiocese were placed individually in folders and arranged chronologically in file cabinets. One cabinet contained original material and another held typescripts, photostats, and other copies of documents held by other Archives that were gathered as part of the research effort. The outside of each folder noted the author and the recipient of the letter. In addition, several letters were sound in another section of the Archives. It is apparent that these letters were placed in the Archives after Lord, Sexton, and Harrington had completed their initial arrangement of manuscripts relating to the history of the Archdiocese of Boston. In preparing this collection of the original Williams material, a calendar was produced. -

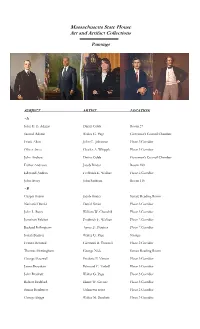

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

The Time Is 12:24

18 THE VIDEOGRAPHER: The time is 12:24. 12:24:26 19 This is Cassette 2 in the deposition of 12:24:59 20 Cardinal Law. We're on the record. 12:24:59 21 Q Cardinal Law, just so the record is clear, 12:25:02 22 before you left as vicar general of Jackson, 12:25:06 23 Mississippi, you had had this conversation with 12:25:11 24 Father Broussard; is that correct? 12:25:14 105 1 A That's correct. 12:25:14 2 Q And you took no action to notify the 12:25:15 3 individuals at St. Peter's Parish that you can 12:25:19 4 recall at this time; is that correct? 12:25:21 5 A That's correct. 12:25:25 6 Q And did you also know a Father Thomas Boyce? 12:25:25 7 A I did. 12:25:28 8 Q And was Father Thomas Boyce also an individual 12:25:29 9 who came to your attention as a priest who had 12:25:33 10 molested children in Jackson, Mississippi, when 12:25:36 11 you were serving as vicar general? 12:25:39 12 A I don't have an active recall of that, but if 12:25:43 13 you bring the case before me, I might -- it 12:25:46 14 might come to light. 12:25:49 15 Q I don't have any case to bring in front of you. 12:25:52 16 I'm just asking whether you have -- your memory 12:25:54 17 might be refreshed between now and the time we 12:25:58 18 come back, which is fine. -

Inhabiting New France: Bodies, Environment and the Sacred, C.1632-C.1700

Inhabiting New France: Bodies, Environment and the Sacred, c.1632-c.1700 Robin Macdonald PhD University of York History September 2015 2 Abstract The historiography of colonial and ‘religious’ encounters in New France has tended to focus on encounters between human beings, between ‘colonisers’ and ‘colonised’ or ‘natives’ and ‘newcomers’. This thesis will focus on encounters between people and environment. Drawing on recent anthropology, notably the work of Tim Ingold, it will argue that whilst bodies shaped environment, environment also could shape bodies – and their associated religious practices. Through the examination of a broad variety of source materials – in particular, the Jesuit Relations – this thesis will explore the myriad ways in which the sacred was created and experienced between c.1632 and c.1700. Beginning with the ocean crossing to New France – an area largely unexplored in the historiographical literature – it will argue that right from the outset of a missionary’s journey, his or her practices were shaped by encounters with both humans and non-humans, by weather or the stormy Ocean Sea. Reciprocally, it will argue, missionary bodies and practices could shape these environments. Moving next to the mission terrain, it will analyse a variety spaces – both environmental and imaginary – tracing the slow build up of belief through habitual practices. Finally, it will chart the movement of missionaries and missionary correspondence from New France back to France. It was not only missionaries, it will argue, who could experience -

“The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk”

circle of supporters to dissociate himself when the cracks in the convent he had just left. He was further convinced that the story appeared, and to admit his misgivings in his she had never been in the Hotel Dieu. He published his “The Awful Disclosures of newspaper. Samuel B. Smith, editor of a rival nativist findings in tracts and editorials, and though he was much newspaper with the colorful title The Downfall of Babylon, attacked in return, his testimony reduced Maria Monk's Maria Monk” also supported Maria Monk's story, despite the profits it following. was providing for his rival, Brownlee. In an effort to gather Maria Monk continued to lose credibility with the Ruth Hughes his share of the spoils, he first published his own tract: public. In 1837, she ran off to Philadelphia with an Decisive confirmation of the Awful disclosures. When that unidentified male companion. She later claimed that she The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, as Exhibited in failed to sell well, he produced his own escaped nun, had been abducted by a group of priests who took her to a Narrative of Her Sufferings During a Residence of Five calling her Saint Francis Patrick and claiming that she, too, Philadelphia with the intention of eventually returning her Years as a Novice and Two Years as a Black Nun, in the had escaped from the Hotel Dieu. Her story was published to Montreal. She sought refuge in the home of a physician, Hotel Dieu Nunnery in Montreal was first published in as The escape of Sainte Francis Patrick, another nun of the William Willcocks Sleigh. -

People of the Dawnland and the Enduring Pursuit of a Native Atlantic World

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MATTHEW R. BAHAR Norman, Oklahoma 2012 “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. Joshua A. Piker, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Catherine E. Kelly ______________________________ Dr. James S. Hart, Jr. ______________________________ Dr. Gary C. Anderson ______________________________ Dr. Karl H. Offen © Copyright by MATTHEW R. BAHAR 2012 All Rights Reserved. For Allison Acknowledgements Crafting this dissertation, like the overall experience of graduate school, occasionally left me adrift at sea. At other times it saw me stuck in the doldrums. Periodically I was tossed around by tempestuous waves. But two beacons always pointed me to quiet harbors where I gained valuable insights, developed new perspectives, and acquired new momentum. My advisor and mentor, Josh Piker, has been incredibly generous with his time, ideas, advice, and encouragement. His constructive critique of my thoughts, methodology, and writing (I never realized I was prone to so many split infinitives and unclear antecedents) was a tremendous help to a graduate student beginning his career. In more ways than he probably knows, he remains for me an exemplar of the professional historian I hope to become. And as a barbecue connoisseur, he is particularly worthy of deference and emulation. -

CATHOLIC DIRECTORY 2020 Edition BAY AREA LOCATION Religous Gifts & Books, Church Goods & Candles BAY AREA LOCATION Religous Gifts & Books, Church Goods & Candles

ARCHDIOCESE OF SAN FRANCISCO CATHOLIC DIRECTORY 2020 Edition BAY AREA LOCATION Religous Gifts & Books, Church Goods & Candles BAY AREA LOCATION Religous Gifts & Books, Church Goods & Candles NowNow with with 5 5 locations locations to serveserve you: you: Northern California S.San Francisco 369 Grand Ave 650-583-5153 NortthernCentral California California S.Modesto San Francisco 2900 369 Standiford Grand Ave.Ave 209-523-2579650-583-5153 Fresno-moved! 3061 W. Bullard Ave 559-227-7373 CentralSouthern California California Now ModestoLos with Angeles 5 locations 17012900 James toStandiford Mserve Wood you: Ave. 213-385-3366 209-523-2579 Northern California LongS.San Beach Francisco 1960 369 GrandDel Amo Ave Blvd 562-424-0963650-583-5153 Central California FresnoModesto - moved! 2900 3061 Standiford W. Bullard Ave Ave. 209-523-2579559-227-7373 Fresno- moved! 3061 W. Bullard Ave 559-227-7373 SouthernSouthern California California LosLos Angeles 17011701 James James M Wood M Wood 213-385-3366213-385-3366 www.cotters.com Long Beach 800-446-3366 1960 Del Amo [email protected] Blvd 562-424-0963 Long Beach 1960 Del Amo Blvd 562-424-0963 www.cotters.com 800-446-3366 [email protected] 2020 ARCHDIOCESE OF SAN FRANCISCO DIRECTORY 1 Archdiocese ......................................... Pages 3 – Insignia and Mission . 3 – Past Archbishops and Auxiliary Bishops; Titles and Statistics . 4 – Regional Dioceses and Other Assemblies . 6 – Archbishop and Auxiliary Bishops . 8 – Archbishop’s Boards and Councils . 10 – Honorary Prelates . 11 – Pastoral Center . 12 – Youth Groups and Young Adults . 16 Clergy / Religious ........................................ 18 – Priest Information . 19 – Deacon Information . 30 – Religious Orders of Men . 34 – Religious Orders of Women . -

The Adam Mickiewicz Institute Report 2017/2018

2017/2018 The Adam Mickiewicz Institute Report 2017/2018 The Adam Mickiewicz Institute Report Adam Mickiewicz Institute Mokotowska Street 25 00-560 Warszawa www.iam.pl www.culture.pl Director: Krzysztof Olendzki Deputy Directors: Ewa Bogusz-Moore Michał Laszczkowski Dariusz Sobkowicz Managers Katarzyna Goć-Cichorska, Marta Jazowska, Maria Karwowska, Dorota Kwinta, Anna Łojko, Zofia Machnicka, Andrzej Mańkowski, Maria Ostrowska, Iwona Patejuk, Małgorzata Łobocka-Stępińska, Joanna Stryjczyk, Michał Szostek, Aneta Prasał-Wiśniewska, Łukasz Strusiński, 2017/2018 Lucyna Szura, Karol Templewicz, Małgorzata Ustymowicz, Artur Wojno, Iga Zawadzińska, Zofia Zembrzuska, Małgorzata Kiełkiewicz-Żak. Texts: Monika Gołębiowska The Adam Mickiewicz Institute Design: Arte Mio Report Translations: Joanna Dutkiewicz Production: Agata Wolska ©Instytut Adama Mickiewicza, Warszawa 2018 Foreword 7 FILM DESIGN PERFORMING ARTS Introduction 8 Polish Film Festival 44 Identity of Design 68 East European Performing Arts Platform (EEPAP) 102 Jan Lenica Retrospective 45 Polish Fashion in Paris 69 G.E.N VR – Extended Reality 104 CLASSICAL MUSIC Polish Icons 46 Exhibition: Textura. A Polish Touch 70 Polish Culture at Hong Kong Festivals 105 Polish Classical Music at Santa Marcelina Cultura 14 DOC LAB POLAND 2018 47 Creative Observatory 71 Apparatum: Installation by the panGenerator Group 106 Polish Music at Rome’s Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia 15 WATCH Out! Polish Filmmakers 48 Exhibition: The ABCs of Polish Design 72 National Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra filmPOLSKA Festival 50 Activated City Workshops 74 CULTURE.PL Performed in China 16 Capturing Freedom 51 Design Dialogue: Poland-Brazil 75 Culture.pl Gets a Facelift 110 Polish Music in Huddersfield 17 Cinema in Mokotowska Street 52 Back to Front 76 Stories from the Eastern West 111 Polish Jazz Bands Tour China 18 Baku Romanticism 53 Art Food Exhibition 77 Soft Power. -

Resisting National Sentiment: Friction Between Irish and English Jesuits in the Old Society

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 598-626 brill.com/jjs Resisting National Sentiment: Friction between Irish and English Jesuits in the Old Society Thomas M. McCoog, S.J. Loyola University Maryland [email protected] Abstract Pedro de Ribadeneyra, first official biographer of Ignatius of Loyola, showered praise upon him and his companions for abandoning immoderate sentiment “for particular lands or places” in their quest for “the glory of God and the salvation of their neigh- bors.” Superior General Goswin Nickel praised a Society conceived in Spain, born in France, approved in Italy, and propagated in Germany and elsewhere. Out of diversity Ignatius had forged unity. Ribadeneyra prayed that nothing would ever threaten this union. His prayers were not heard: the Society’s internal unity was often endangered by national sentiment despite congregational attempts to curtail and eliminate it. This article does not purport to be an exhaustive study of localism versus international- ism—although such a study is needed—but an investigation of relations between Irish and English Jesuits principally in the seventeenth century. Individual Jesuits did in fact cooperate, but there were limits. A proposal in 1652 that the independent Irish mission become part of the English mission was that limit. Keywords Irish Jesuits – English Jesuits – John Young – national sentiment – Muzio Vitelleschi – Gian Paolo Oliva – general congregations 1 Introduction: the Internationalism of the Society of Jesus In the spring of 1539, Ignatius of Loyola (c.1491–1556; in office, 1541–56) and his companions deliberated their future. Should they attempt to retain some union, a corporate identity, despite their being sent in different directions on © Thomas M. -

Winthrop's Journal : "History of New England", 1630-1649

LIBRARY ^NSSACHt,^^^ 1895 Gl FT OF WESTFIELD STATE COLLEGE LIBRARY ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY REPRODUCED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION General Editor, J. FRANKLIN JAMESON, Ph.D., LL.D. DIRECTOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OP HISTORICAL RESEARCH IN THE CAKNBGIB INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON WINTHROFS JOURNAL 1630 — 1649 Volume I r"7 i-^ » '^1- **. '* '*' <>,>'•*'' '^^^^^. a.^/^^^^ ^Vc^^-f''f >.^^-«*- ^»- f^*.* vi f^'tiy r-^.^-^ ^4w;.- <i 4ossr, ^<>^ FIRST PAGE OF THE WINTHROP MANUSCRIPT From the original in the Library of the Massachusetts Historical Society ORIGINAL NARRATIVES OF EARLT AMERICAN HISTORY WINTHROP'S JOURNAL "HISTORY OF NEW ENGLAND" 1630—1649 EDITED BY JAMES KENDALL HOSMER, LLD. CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY AND OF THE COLONIAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS WITH MAPS AND FA CI ^^eStF^^ NORMAL SCHOOL VOLUME I CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS NEW YORK 1908 \^ c-4 COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS Published June, 1908 \J . 1 NOTE While in this edition of Winthrop's Journal we have followed, as Dr. Hosmer explains in his Introduction, the text prepared by Savage, it has been thought wise to add devices which will make the dates easier for the reader to follow; but these have, it is hoped, been given such a form that the reader will have no difficulty in distinguishing added words or figures from those belonging to the original text. Winthrop makes no division into chapters. In this edition the text has, for the reader's convenience, been broken by headings repre- senting the years. These, however, in accordance with modern usage, have been set at the beginning of January, not at the date with which Winthrop began his year, the first of March.