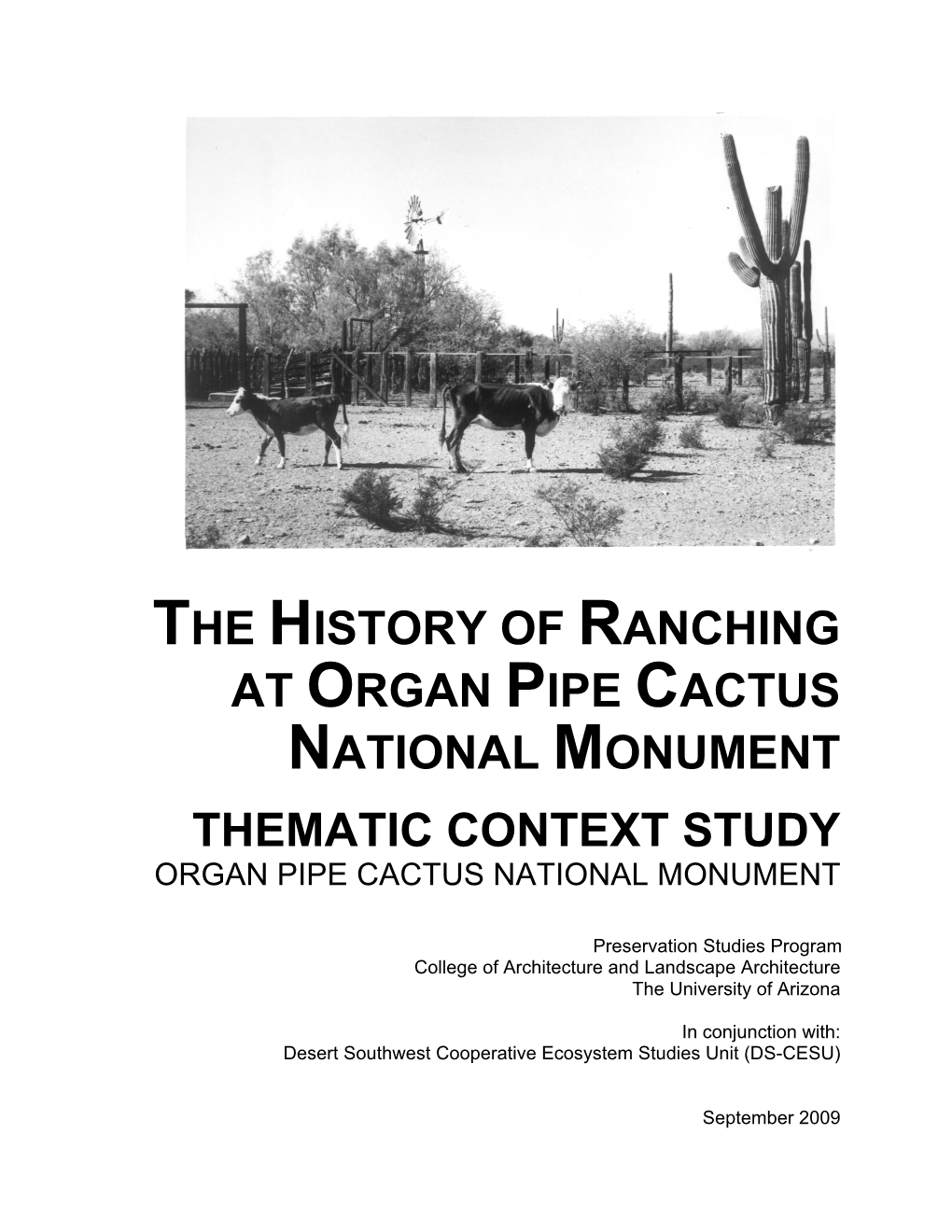

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument History of Ranching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endangered Species Bulletin, May/June 2003 - Vol

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Endangered Species Bulletins and Technical Reports (USFWS) US Fish & Wildlife Service May 2003 Endangered Species Bulletin, May/June 2003 - Vol. XXVIII No. 3 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/endangeredspeciesbull Part of the Biodiversity Commons "Endangered Species Bulletin, May/June 2003 - Vol. XXVIII No. 3" (2003). Endangered Species Bulletins and Technical Reports (USFWS). 10. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/endangeredspeciesbull/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Fish & Wildlife Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Endangered Species Bulletins and Technical Reports (USFWS) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Human beings are the only living things that care about lines on a map. Wild animals and plants know no borders, and they are unaware of the social and economic forces that deter- mine their future. Because May/June 2003 Vol. XXVIII No. 3 many of these creatures are migratory or distributed across the artificial bound- aries that we humans have drawn, they cannot be con- served without the coopera- tion of government, private sector, and scientific partners in each of the affected coun- tries. Such wide-scale partici- pation is essential for apply- ing an ecosystem approach to wildlife conservation. This edition of the Bulletin features some examples of cooperative activities for the survival and recovery of rare plants and animals in Mexico and bordering areas of the United States. U.S.U.S. -

Read John Rhodes' Oral History Transcript

John Rhodes_Transcript.docx Page 1 of 31 CAP Oral History Interview with John Rhodes February 11, 1999 (C: being interviewer Crystal Thompson) C: I was just describing your background a little bit. Were you born and raised in Arizona? John: Sorry. C: Were you born and raised here? John: No, incidentally, my ears are reasonably good for 82 years old, but they’re 82 years old. C: Okay, I’ll speak up. John: As my children keep saying, dad you should get a hearing aid. I said no I don’t need a hearing aid; I just need for people like you to articulate better and face me when you speak. I was born and raised in Council Grove, Kansas. My parents were. My father was a retail lumberman and he was born in Kansas also. My mother was born...he was born in a little called Colony and mother was born in Emporia which was a fairly good size town. C: My grandmother was born in Emporia. John: No kidding. C: My mother was raised in Lacygne. John Rhodes_Transcript.docx Page 2 of 31 John: Oh yes, L-A-C-Y-G-N-E there aren’t too many who can spell Lacygne. My mother’s family was Welsh. In fact my maternal grandparents were both Welsh immigrants. It’s coming from about the same part Wales and when Betty and I were in that part of the world once upon a time, we rented a car and drove to the town where my grandmother had lived. I was pretty close to her. -

Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace In

TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: History TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terry H. Anderson Committee Members, Jon R. Bond H. W. Brands John H. Lenihan David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace in Korea. (May 2008) Larry Wayne Blomstedt, B.S., Texas State University; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terry H. Anderson This dissertation analyzes the roles of the Harry Truman administration and Congress in directing American policy regarding the Korean conflict. Using evidence from primary sources such as Truman’s presidential papers, communications of White House staffers, and correspondence from State Department operatives and key congressional figures, this study suggests that the legislative branch had an important role in Korean policy. Congress sometimes affected the war by what it did and, at other times, by what it did not do. Several themes are addressed in this project. One is how Truman and the congressional Democrats failed each other during the war. The president did not dedicate adequate attention to congressional relations early in his term, and was slow to react to charges of corruption within his administration, weakening his party politically. -

In County; Hathaway Wins

NOGALES’ HOME NEWSPAPER . PUBLISHED WHERE TWO NATIONS MEET FOR VICTORY I For Victory . .. UNITED STATES DEFENSE I * EFENSE BONDS • STAMPS IRogales Internationa! -mps X VOL. 20—NO. 9 NOGALES, ARIZ.. FRIDAY, JULY 21, 1944 FIVE CENTS A COP* Four Brothers Callahan Property REQUIEM MASS ON JULY 31ST Arizona Not For MANYSTAY AWAYFROM POLLS Shut Down S. For IN See Service On Wednesday FOR MEN KILLED IN PACIFIC Wallace COUNTY; HATHAWAY WINS Regimental Chaplain Has Vice President ‘Hi’ Sorrells As A shutdown of all operations went Fire Call To Recognizes Pal Reelected into effect Wednesday at the Calla- Highest Praise For (By CRAIG POTTINGER) County Supervisor han Lead-Zinc Company properties El Progreso After Separation CHICAGO, July 18—(Special) 3 in Santa Cruz County following a Boys Os Co. A In District No. —LTntil the Arizona delegation four-year effort to establish the Wednesday Eve Os 45 Years In response to request by 19 caucuses at 5 p.m. today it is not Less than 60 per cent of Santa company’s holdings on a permanent a local men in the 158th Infantry known who they will favor for Cruz County’s registered voters basis. Smoke began billowing from C. O. Strickland of Nogales in New Guinea, a Solemn Re- vice president. went to the polls Tuesday to re- About 25 workers will continue on the newly reconstructed El Pro- stopped an elderly man on the quiem Mass for three members of One delegate is for Henry Wal- elect the incumbents in the only the job dismantling machinery that greso Wednesday night and street Saturday and said, “Don’t their company who have died in lace, another for Justice Douglas, two races in which there were is being shipped to another holding- throngs on the street were sure I know you?” The man looked service will be held in Sacred others favor James F. -

Organ Pipe Cactus U.S

National Park Service Organ Pipe Cactus U.S. Department of the Interior Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument 2010-2011 Tillotson Peak Welcome to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument The Making of a Monument Superintendent’s Welcome Until slightly more than 100 years ago only a few people inhabited this part of the Sonoran Welcome to Organ Pipe Cactus National Desert. Except for Native Americans, most were transient. Monument. We work hard to make your visit a pleasant, memorable and safe experience. Early in the 20th century, a few intrepid scientific explorers visited this region. They compiled Our knowledgeable and capable staff is ready copious data along with photographs and drawings of the plants, wildlife and geology. When to answer your questions so you can enjoy their scientific reports were published, news of their discoveries of previously undocumented the unique Sonoran Desert landscape and the plants and animals spread worldwide. cultural and historical sites in the monument. By 1920, miners were commercially mining the copper deposits in Ajo. The incursions of Kris Eggle Visitor Center, with its newly ranchers, miners, hunters, and others left roads, trails, buildings and mine tailings throughout remodeled exhibit and museum area, is both the area. interesting and beautiful. Our educational Superintendent Lee Baiza book and gift store has many items to help As commerce expanded across the desert, there were those who sought to protect its natural you remember your visit. We continue to wonders. In the 1920s, the Tucson Natural History Association, later known as the Tucson improve our park infrastructure which includes Audubon Society, conducted tourist excursions here. -

Environmental Protection Agency Region 5 Electronic Data Deliverable Valid Values Reference Manual

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 5 ELECTRONIC DATA DELIVERABLE VALID VALUES REFERENCE MANUAL Appendix to EPA Electronic Data Deliverable (EDD) Comprehensive Specification Manual . March, 2019 ELECTRONIC DATA DELIVERABLE VALID VALUES REFERENCE MANUAL Appendix to EPA Electronic Data Deliverable (EDD) Comprehensive Specification Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS Table A-1 Matrix .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Table A-2 Coord Geometric type .................................................................................................................. 7 Table A-3 Horizontal Collection Method ..................................................................................................... 7 Table A-4 Horizontal Accuracy Units .......................................................................................................... 8 Table A-5 Horizontal Datum ........................................................................................................................ 8 Table A-6 Elevation Collection Method ....................................................................................................... 8 Table A-7 Elevation Datum .......................................................................................................................... 9 Table A-8 Material ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Table -

Chapter 3. Affected Environment Lower Sonoran/SDNM Draft RMP/EIS 253

Chapter 3. Affected Environment Lower Sonoran/SDNM Draft RMP/EIS 253 3.1. INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the environment within the Lower Sonoran Planning Area that would potentially be affected by actions proposed under the alternatives described in Chapter 2, Alternatives (p. 27). While the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is only responsible for managing BLM-administered public lands (public lands) within the Planning Area (i.e. the Lower Sonoran and Sonoran Desert National Monument [SDNM] Decision Areas), proposed decisions may affect environmental components outside the Decision Areas. Therefore, unless indicated otherwise, discussion and analysis in this section encompasses the Planning Area as a whole. The environmental components potentially impacted consist of resource and management activities listed below. The foreseeable environmental effects of the alternatives on these same resource and management activities are described in Chapter 4, Environmental Consequences (p. 371). Resources Resource Uses Air Quality Lands and Realty Cave Resources Livestock Grazing Management Climate Change Minerals Management Cultural and Heritage Resources Recreation Management Geology Travel Management Paleontological Resources Special Area Designations Priority Wildlife Species and Habitat Management National Landscape Conservation System Soil Resources Administrative Designations Vegetation Resources Other Special Designations Visual Resources Social and Economic Water Resources Tribal Interests Wild Horse & Burro Management Hazardous Materials and Public Safety Wilderness Characteristics Social and Economic Conditions Wildland Fire Management The data and descriptions of these categories are drawn from the Analysis of the Management Situation (AMS) (BLM 2005) and subsequent, completed resource assessments on several of the environmental components occurring within the Planning Area. The AMS is available for public review at the BLM’s Phoenix District Office. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

ARIZONA WATER ATLAS Volume 1 Executive Summary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Arizona Department of Water Resources September 2010 ARIZONA WATER ATLAS Volume 1 Executive Summary ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Director, Arizona Department of Water Resources Herbert Guenther Deputy Director, Arizona Department of Water Resources Karen Smith Assistant Director, Hydrology Frank Corkhill Assistant Director, Water Management Sandra Fabritz-Whitney Atlas Team (Current and Former ADWR staff) Linda Stitzer, Rich Burtell – Project Managers Kelly Mott Lacroix - Asst. Project Manager Phyllis Andrews Carol Birks Joe Stuart Major Contributors (Current and Former ADWR staff) Tom Carr John Fortune Leslie Graser William H. Remick Saeid Tadayon-USGS Other Contributors (Current and Former ADWR staff) Matt Beversdorf Patrick Brand Roberto Chavez Jenna Gillis Laura Grignano (Volume 8) Sharon Morris Pam Nagel (Volume 8) Mark Preszler Kenneth Seasholes (Volume 8) Jeff Tannler (Volume 8) Larri Tearman Dianne Yunker Climate Gregg Garfin - CLIMAS, University of Arizona Ben Crawford - CLIMAS, University of Arizona Casey Thornbrugh - CLIMAS, University of Arizona Michael Crimmins – Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Science, University of Arizona The Atlas is wide in scope and it is not possible to mention all those who helped at some time in its production, both inside and outside the Department. Our sincere thanks to those who willingly provided data and information, editorial review, production support and other help during this multi-year project. Arizona Water Atlas Volume 1 CONTENTS SECTION 1.0 Atlas Purpose and Scope 1 SECTION 1.1 Atlas -

CVNA History1.Pdf

Historical Overview Summary The Catalina Vista Historic District is located in close proximity to the University of Arizona in Tucson. The district is located north and east of the University's main campus and directly east of its medical school. Catalina Vista takes its name from a single subdivision, first developed in 1940. The Catalina Vista Historic District is considered significant under National Register criterion "A" for is association with community development in Tucson. Community development significance is described by the historic context "Tucson Subdivisions in Transition, 1940-1955 ." The historic district is also considered significant under National Register criterion "C" as being representative of architectural styles dominant in Tucson during World War Two and.the post-WWII transitional era. Architectural significance is described by the historic context "Tucson Architectural Styles in Transition, 1940-1955," Although the transitional era of community and architectural development took place from 1940 to 1955, the period of significance for the Historic District starts in 1903 when suburban residential development first began in district area and ends in 1951 at the fifty-year limit for National Register significance. This period of significance allows for the inclusion of the "Potter Place" property under the historical context "Residential Subdivision Development in Tucson, 1903- 1940 ." The Catalina Vista neighborhood, of Tucson is located in' Section 5 of Township 14 South, Range 14 East, of the Crila and- Salt River Base and Meridian in Arizona. Section 5 originally consisted of four separate parcels of land granted by the US government . Calvert Wilson received the first of these grants, taking possession by cash payment of about 160 acres in the northwest corner of the section in 1891 . -

History of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/historyofquitobaOOnati ; 2 ? . 2 H $z X Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit ARIZONA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 2 6 A History of the Quitobaquito Resource Management Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona by Peter S. Bennett and Michael R. Kunzmann University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 Western Region National Park Service Department of the Interior San Francisco, Ca. 94102 COOPERATIVE NATIONAL PARK RESOURCES STUDIES UNIT University of Arizona/Tucson - National Park Service The Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit/University of Arizona (CPSU/UA) was established August 16, 1973. The unit is funded by the National Park Service and reports to the Western Regional Office, San Francisco; it is located on the campus of the University of Arizona and reports also to the Office of the Vice-President for Research. Administrative assistance is provided by the Western Arche- ological and Conservation Center, the School of Renewable Natural Resources, and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. The unit's professional personnel hold adjunct faculty and/or research associate appointments with the University. The Materials and Ecological Testing Laboratory is maintained at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center, 1415 N. 6th Ave., Tucson, Arizona 85705. The CPSU/UA provides a multidisciplinary approach to studies in the natural and cultural sciences. Funded projects identified by park management are investigated by National Park Service and university researchers under the coordination of the Unit Leader. Unit members also cooperate with researchers involved in projects funded by non-National Park Service sources in order to obtain scientific information on Park Service lands. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 12, 2021 No. 82 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was impacted by horrific events. They pre- I wholeheartedly agree with my called to order by the Speaker pro tem- vent the tragedy from fading from our friend, the chief of police in Chambers- pore (Mr. CORREA). memories by educating the generations burg, and Congress must do our part to f to come, and they highlight the mod- support these heroes. Instead of talk- ern-day implications of such events. ing about defunding the police, we DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO My resolution would provide a day should be working to better train and TEMPORE for slavery remembrance, and the lan- equip law enforcement officers to do The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- guage of the resolution would com- the job that we have entrusted them to fore the House the following commu- memorate the lives of all enslaved peo- do. nication from the Speaker: ple, while condemning the act and the As we move forward, the American WASHINGTON, DC, perpetration as well as perpetuation of people know that Republicans are lead- May 12, 2021. slavery in the United States of Amer- ing commonsense, bipartisan solutions. I hereby appoint the Honorable LUIS J. ica and across the world. For over a year, Senator TIM SCOTT CORREA to act as Speaker pro tempore on The resolution would discuss the and Congressman PETE STAUBER have this day.