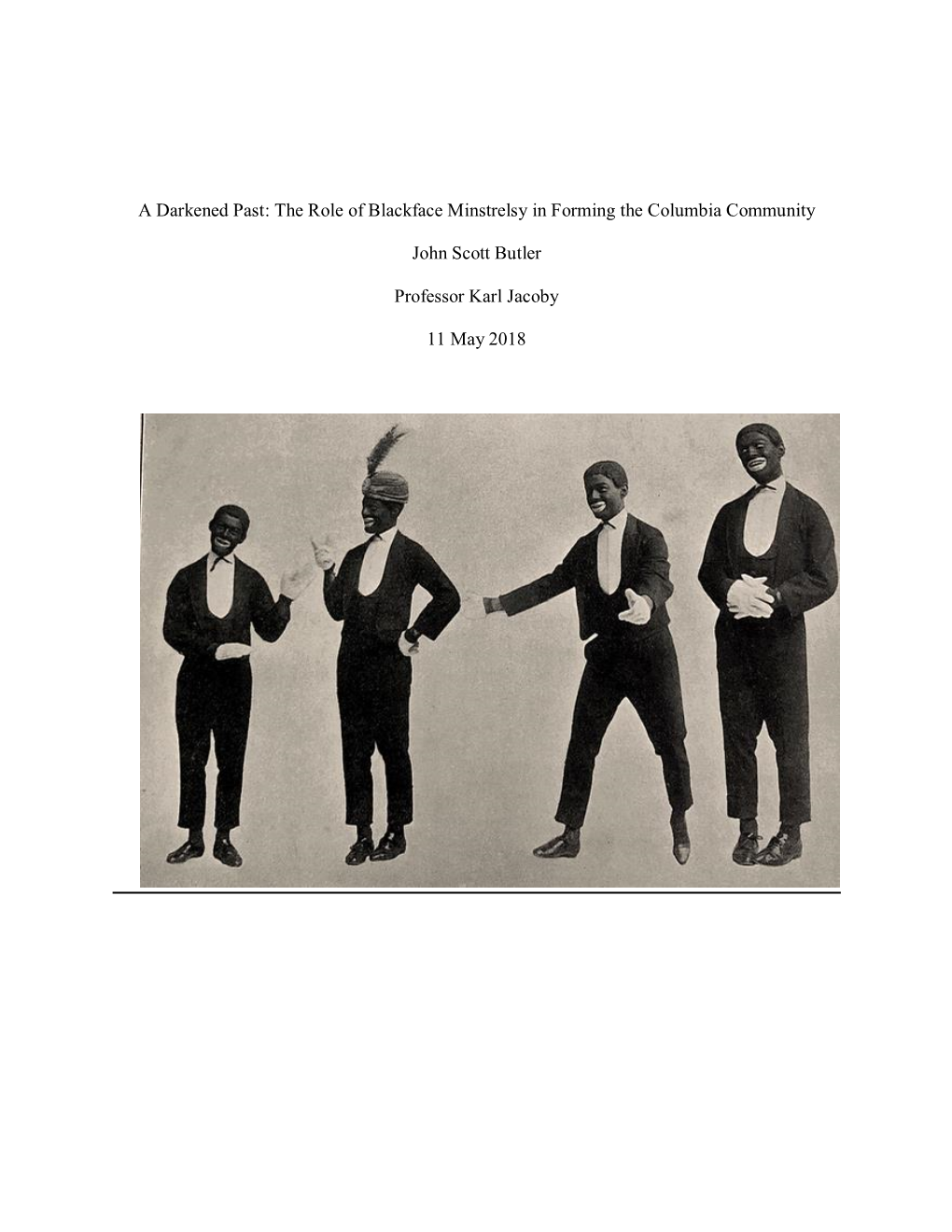

A Darkened Past: the Role of Blackface Minstrelsy in Forming the Columbia Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Maine Stations Carry Colby's First Varsity Show

~ , I . I I MHH~~ ,' . - ,' Track Meet Mere Reading Knowledge . With Norwich Examinations Saturday Afternoon Tomorrow Afternoon Geology Stud ents " liiferarf Associates Meet To Leave Frida y "Prexy Johnson Decides Prob Fifteen Plan To Take 3O0 able Winning Run Mile Trip To Bar Harbor y Pirdfes sors Weber , Wilkinson , And In Favor Of Facilit This Friday fifteen of the Geology Mars hall Are Speake rs For classes will make a three-hundredmile Cap And Gown Elects Picnic Closes With Singing trip that will take in a complete study Gf Alma Mater of the Geological features in and Seven New Members Eveni ng around Bar Harbor. This excursion has been an annual feature for many Over four hundred wildly stamping, years having been started probably Purpose Of Society To Initi- Book Exhibit Is Held In rd Represents , madly yelling specimens of the most Packa by the late Professor Perkins. ate And Promote College rabid "type of Gus H. Fan known to Social Room OF Alumnae Moot Court The group will leave Friday noon captivity stampeded for the over- Marshall and' will spend the two nights while Activities And Standards flowing food tables when our un- Building at the Y. W. C. A. in Mr. Joseph Packard, son of Mr. they are away, biased arbiter "Prexy" Johnson stop- Bar Harbor. The small group that and Mrs. Thomas P. Packard of 3 ped all athletic proceedings because Tuesday evening, May 10, the first will remain to take in the fraternity At women's assembly, Monday Prospect St., Houlton, Maine, first morning, of Midget - Peck's mighty homer and regular* meeting of the Colby Library Friday night, will May 16, the annual induc- year student at Columbia Law School dances at Colby consequent lost nail in deep left field Associates was held in the Y. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Patricia R

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College English Faculty Publications English Department 6-9-2010 Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Patricia R. Schroeder Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/english_fac Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Patricia R., "Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race" (2010). English Faculty Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/english_fac/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Until recently, scholars exploring blackface minstrelsy or the accompanying “coon song craze” of the 1890s have felt the need to apologize, either for the demeaning stereotypes of African Americans embedded in the art forms or for their own interest in studying the phenomena. Robert Toll, one of the first critics to examine minstrelsy seriously, was so appalled by its inherent racism that he focused his 1974 work primarily on debunking the stereotypes; Sam Dennison, another pioneer, did likewise with coon songs. Richard Martin and David Wondrich claim of minstrelsy that “the roots of every strain of American music—ragtime, jazz, the blues, country music, soul, rock and roll, even hip-hop—reach down through its reeking soil” (5). -

Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.hemisferica.org “You Make Me Feel So Young”: Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy by Eric Lott | University of Virginia In 1965, Frank Sinatra turned 50. In a Las Vegas engagement early the next year at the Sands Hotel, he made much of this fact, turning the entire performance—captured in the classic recording Sinatra at the Sands (1966)—into a meditation on aging, artistry, and maturity, punctuated by such key songs as “You Make Me Feel So Young,” “The September of My Years,” and “It Was a Very Good Year” (Sinatra 1966). Not only have few commentators noticed this, they also haven’t noticed that Sinatra’s way of negotiating the reality of age depended on a series of masks—blackface mostly, but also street Italianness and other guises. Though the Count Basie band backed him on these dates, Sinatra deployed Amos ‘n’ Andy shtick (lots of it) to vivify his persona; mocking Sammy Davis Jr. even as he adopted the speech patterns and vocal mannerisms of blacking up, he maneuvered around the threat of decrepitude and remasculinized himself in recognizably Rat-Pack ways. Sinatra’s Italian accents depended on an imagined blackness both mocked and ghosted in the exemplary performances of Sinatra at the Sands. Sinatra sings superbly all across the record, rooting his performance in an aura of affection and intimacy from his very first words (“How did all these people get in my room?”). “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Jilly’s West,” he says, playing with a persona (habitué of the famous 52nd Street New York bar Jilly’s Saloon) that by 1965 had nearly run its course. -

Blackface: a Reclamation of Beauty, Power, and Narrative April 20 – June 15, 2019 Exhibition Essay - Black Face: It Ain’T About the Cork by Halima Taha

Blackface: A Reclamation of Beauty, Power, and Narrative April 20 – June 15, 2019 Exhibition Essay - Black Face: It Ain’t About the Cork by Halima Taha Blackface: It Ain’t About the Cork c 2019 Halima Taha Galeriemyrtis.net/blackface Black Face: It Ain’t About the Cork Currently ‘blackface’ has been used to describe a white adult performing a nauseatingly racist caricature of a black person; to a pair of pre-teen girls who never heard the word ‘minstrelsy’ when experimenting with costume makeup at a sleep over-- yet ‘blackfaced’ faces continue to be unsettling. Since the 19th century a montage of caricaturized images of black and brown faces, from movies, books, cartoons and posters have been ever present in the memories of all American children. Images of the coon, mammy, buck, sambo, pick-a-ninny and blackface characters, portrayed in subservient roles and mocking caricatures include images from Aunt Jemima at breakfast, to the1930’s Little Rascals, Shirley Temple in The Littlest Rebel, Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd in blackface on Saturday morning TV; to Uncle Ben staring from the cupboard-- all reinforced the demeaning representations of African Americans created to promote American white supremacy. The promotion of this ideal perpetuates the systemic suppression and suffocation of the black being. For many African Americans these images of themselves evoke an arc of emotions including: anger, sadness confusion, hurt--invisibility and shame. In 1830 Thomas Dartmouth Rice known as the “Father of Minstrelsy” developed a character named Jim Crow after watching enslaved Africans and their descendants reenacting African storytelling traditions that included folktales about tricksters, usually in the form of animals. -

The 114Th Annual Varsity Show “Morningside Hates”

THE UNDERGRADUATE MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY , EST . 1890 The Varsity Show May 2008 THE 114TH ANNUAL VARSITY SHOW “Morningside Hates” May 2, 3, and 4 in Roone Arledge Auditorium ALSO : CAN YOU MAKE A VARSITY SHOW ? THE WRITERS ’ NOTEBOOK PLAYBILL STAFF Editor ANNA PHILLIPS Managing Editor KATIE REEDY Senior Editors JULI WEINER HANNAH GOLDFIELD Layout Editor JUSTIN VLASITS Consigliere ZACHARY VAN SCHOUWEN Copy Chief ALEXANDER STATMAN Artists JULIA BUTAREVA JENNY LAM MAXINE KEYES SONIA TYCKO Contributors BECKY ABRAMS PAUL B. BARNDT ANNA LOUISE CORKE ANDREW MCKAY FLYNN TONY GONG KATE LINTHICUM JOSEPH MEYERS MICHAEL MOLINA CHRISTOPHER MORRIS-LENT ALEXEXANDRA MUHLER MARYAM PARHIZKAR MARIELA QUINTANA ALEX WEINBERG Editor Emerita TAYLOR WALSH 2 THE BLUE AND WHITE THE BLUE AND WHITE Vol. CXIV THE VARSITY SHOW No. MMMML 4 THE CAST OF CHARACTERS . .Your new best friends for the next two hours. 5 SCENES AND SONGS . Whatever happens, happens. 6 CAST AND CREW . Because Facebook profiles aren’t enough. 16 THE VARSITY GLOSSARY . Columbia for dummies. 18 A CONVERSATION WITH THE WRITERS . .It takes two to do it right. 21 FROM THE WRITERS ’ NOTEBOOKS . How are we going to end this show again? 22 114 YEARS OF VARSITY DRAMA . No one ever remembers. 23 BEHIND THE SCENES . The art of unpaid labor. 26 CAN YOU MAKE A VARSITY SHOW ? . A quiz for JV scribblers. 27 VARSITY GOSSIP . The feverish ramblings of the co-lyricist, plus cupcakes. he Varsity Show was born in 1894, four gloriously quiet years after THE BLUE AND WHI T E emerged from Alma Mater’s iron womb. As the bookish older sibling sat doodling in the corner, the Columbia family gathered around the precocious little runt. -

People Don't Realize How Hard It Is to Get Into the Varsity Show. Auditions

CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 Cast and Crew 5 Scene and Song Order 6 Biographies 11 Conversation 13 Failed Auditions 14 Timeline 16 Digitalia Varsitana 17 Lecture Notes 18 Varsity Show Gossip 19 Acknowledgements & DVD/CD Ordering Info Typographical Note The text of The Blue and White is set in Bodoni Old Face, which was revived by Günter Gerhard Lange based on original designs by Giambattista Bodoni of Parma (active 1765–1813). The display faces are Weiss and Cantoria. 2 The Blue & White The Varsity Show 3 THE BLUE AND WHITE THE VARSITY SHOW PLAYBILL ignificant alliances, partnerships, and coalitions are formed everywhere, every day. Who, for example, could forget the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact? Not Poland! For that matter, mutu- ally-beneficial exchanges play an integral role even at our fine school. Between Columbia College and SEAS students: “You do my problem set, I’ll read the Iliad for you.” Between the ladies of Barnard and Columbia: “You Take Back The Night, we’ll give you back your men.” Between the Office of University Development and the United Arab Emirates: “You give us 2.1 million dol- lars, we’ll give you an Edward Said Chair for Middle Eastern Studies.” Over the last two years, the Varsity Show and The Blue and White have enjoyed their own especially rewarding relationship. For instance, dur- ing tonight’s performance of Off Broadway, the Varsity Show will prove remarkably adept at wowing the audience with catchy tunes, flashy lights, and jokes at Barnard’s expense (it’s so easy). But what is the audience expected to do while waiting for the show to begin? Enter The Blue and White. -

1920 Patricia Ann Mather AB, University

THE THEATRICAL HISTORY OF WICHITA, KANSAS ' I 1872 - 1920 by Patricia Ann Mather A.B., University __of Wichita, 1945 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charf;& Redacted Signature Sept ember, 19 50 'For tne department PREFACE In the following thesis the author has attempted to give a general,. and when deemed.essential, a specific picture of the theatre in early day Wichita. By "theatre" is meant a.11 that passed for stage entertainment in the halls and shm1 houses in the city• s infancy, principally during the 70' s and 80 1 s when the city was still very young,: up to the hey-day of the legitimate theatre which reached. its peak in the 90' s and the first ~ decade of the new century. The author has not only tried to give an over- all picture of the theatre in early day Wichita, but has attempted to show that the plays presented in the theatres of Wichita were representative of the plays and stage performances throughout the country. The years included in the research were from 1872 to 1920. There were several factors which governed the choice of these dates. First, in 1872 the city was incorporated, and in that year the first edition of the Wichita Eagle was printed. Second, after 1920 a great change began taking place in the-theatre. There were various reasons for this change. -

I Was a Teenage Negro! Blackface As a Vehicle of White Liberalism in Finian's Rainbow

I Was a Teenage Negro! Blackface as a Vehicle of White Liberalism in Finian's Rainbow Russell Peterson Obviously we hope you will enjoy your evening with us, but before the curtain goes up we would like to forewarn you about what you will see. Finian s Rainbow is a joyous musical cel ebrating life, love, and the magic that lives in each of us, but it is also something more. Produced in 1947, it was one of the American theater's first attempts to challenge racism and big otry. With the two-edged sword of ridicule and laughter it punctured the stereotypes that corrupted America. In doing so it created something of a stereotype itself. If it seems at times that our cast makes fun of racial or social groups, it is only that we wish to expose and deride the bigotry that still would gain a hearing in our hearts. —program note from Edison Jun ior High School's (Sioux Falls, SD) 1974 production of Finian's Rainbow I might as well confess right up front that this article's title is a bit of a tease. While I did play a sharecropper in Edison Junior High's 1974 production of Finian s Rainbow, I was as white onstage as I was (and am) off. In this case, however, color-coordination of actor and role was less a matter of race-appro priate casting than of directorial whim. Allow me to explain. 0026-3079/2006/4703/4-035$2.50/0 American Studies, 47:3/4 (Fall-Winter 2006): 35-60 35 36 Russell Peterson Finian was a big Broadway hit in 1947. -

THE POLITICAL CRITIQUE of SPIKE Lee's Bamboozled

35 GLOBAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES VOL 8, NO. 1&2, 2009: 35-44 COPYRIGHT© BACHUDO SCIENCE CO. LTD PRINTED IN NIGERIA. ISSN 1596-6232 www.globaljournalseries.com ; [email protected] LEGACIES OF BLACKFACE MINSTRELSY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MEDIA: THE POLITICAL CRITIQUE OF SPIKE Lee’s Bamboozled PATRICK NKANG, JOE KING AND PAUL UGO (Received 24, August 2010; Revision Accepted 3, September 2010) ABSTRACT This paper examines the extraordinary ways in which the America mainstream visual media have propagated and circulated racist myths which subvert the cultural identity of the black race. Using Spike Lee’s Bamboozled , the paper exposes the negative social stereotypes espoused by American entertainment media about blacks, and argues that Spike Lee’s film not only unravels that subversive Euro-American rhetoric, but also doubles as an intense social critique of that warped cultural dynamic. KEYWORDS: Blackface Minstrelsy, Racist Stereotypes and American Media. INTRODUCTION Because slavery is the illuminating insight on this aspect of cinema in the founding historical relationship between black United States when he declares that “the fact that and white in America many will argue, lingers film has been the most potent vehicle of in subterranean form to this day (Guerrero 1993: American imagination suggests all the more 03). strongly that movies have something to tell us about the mysteries of American life” (xii). Film and the African-American Image American films then have a deep historical link with its social environment, providing us the As a form of social expression, the film medium profoundest social transcripts about American embodies significantly staggering amounts of society than historians, economists and other social truths . -

The Minstrel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of “Black” Identities in Entertainment

Africana Studies Faculty Publications Africana Studies 12-2015 The insM trel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment Jennifer Bloomquist Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/afsfac Part of the African American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Bloomquist, Jennifer. "The inM strel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment." Journal of African American Studies 19, no. 4 (December 2015). 410-425. This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/afsfac/22 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The insM trel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of "Black" Identities in Entertainment Abstract Linguists have long been aware that the language scripted for "ethnic" roles in the media has been manipulated for a variety of purposes ranging from the construction of character "authenticity" to flagrant ridicule. This paper provides a brief overview of the history of African American roles in the entertainment industry from minstrel shows to present-day films. I am particularly interested in looking at the practice of distorting African American English as an historical artifact which is commonplace in the entertainment industry today. -

African American Inequality in the United States

N9-620-046 REV: MAY 5, 2020 JANICE H. HAMMOND A. KAMAU MASSEY MAYRA A. GARZA African American Inequality in the United States We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. — The Declaration of Independence, 1776 Slavery Transatlantic Slave Trade 1500s – 1800s The Transatlantic slave trade was tHe largest deportation of Human beings in History. Connecting the economies of Africa, the Americas, and Europe, tHe trade resulted in tHe forced migration of an estimated 12.5 million Africans to the Americas. (Exhibit 1) For nearly four centuries, European slavers traveled to Africa to capture or buy African slaves in excHange for textiles, arms, and other goods.a,1 Once obtained, tHe enslaved Africans were tHen transported by sHip to tHe Americas where tHey would provide tHe intensive plantation labor needed to create HigH-value commodities sucH as tobacco, coffee, and most notably, sugar and cotton. THe commodities were tHen sHipped to Europe to be sold. THe profits from tHe slave trade Helped develop tHe economies of Denmark, France, Great Britain, the NetHerlands, Portugal, Spain and tHe United States. The journey from Africa across tHe Atlantic Ocean, known as tHe Middle Passage, became infamous for its brutality. Enslaved Africans were chained to one another by the dozens and transported across the ocean in the damp cargo Holds of wooden sHips. (Exhibit 2) The shackled prisoners sat or lay for weeks at a time surrounded by deatH, illness, and human waste.