The Minstrel Legacy: African American English and the Historical Construction of “Black” Identities in Entertainment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Champ Readies for Belmont Breeders= Cup

TUESDAY, JUNE 2, 2015 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here THE CHAMP READIES FOR BELMONT GLENEAGLES, FOUND TO BYPASS EPSOM GI Kentucky Derby and GI Preakness S. winner The Coolmore partners= dual Guineas winner American Pharoah (Pioneerof the Nile) registered his last Gleneagles (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) and Group 1-winning filly serious work before Saturday=s GI Belmont S. under Found (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) are no longer under cloudy skies Monday at consideration for Saturday=s Churchill Downs. The bay G1 Epsom Derby, and both covered five panels in will target mile races at 1:00.20 (video) with Royal Ascot. Martin Garcia in the irons Gleneagles was removed shortly after the from the Classic at renovation break. Monday=s scratching stage Churchill clocker John and will head to the G1 St. Nichols recorded 1/8-mile James=s Palace S. on the opening day of the Royal fractions in :13, :25 meeting June 16. Found, (:12), :36.60 (11.60) and who has been second in :48.60 (:12). He galloped Gleneagles winning the Irish both starts this year out six furlongs in 1:13, 2000 Guineas including the G1 Irish 1000 seven-eighths in 1:26 and Racing Post Photo Guineas May 24, will a mile in 1:39.60. contest the G1 Coronation Baffert noted how S. June 19. Found would have had to be supplemented pleased he was with the to the Derby at a cost of ,75,000. Coolmore and American Pharoah work later in the morning. trainer Aidan O=Brien are expected to be represented in Horsephotos AEverything went really the Derby by G3 Chester Vase scorer Hans Holbein well today,@ Hall of Fame (GB) (Montjeu {Ire}), owned in partnership with Teo Ah trainer Bob Baffert said outside Barn 33. -

Thoroughbred

A Publication of the Pennsylvania Horse Breeders Association PAThoroughbred pabred.com November 2017 pabred.com Issue 44 REPORT Blast From the Past: Treizieme PA-Breds Eye One of two PA-breds to compete on the inaugural Breeders’ Cup card at Breeders’ Cup Hollywood Park in 1984, the daughter Three Pennsylvania-breds - Finest of The Minstrel split her time between City, Mor Spirit and Unique Bella - France and the U.S. head into the 34th Breeders’ Cup, to be run at the Del Mar Thoroughbred Page 23 Club Nov. 3 and 4. PA-Breds At Page 3 Kentucky Fall Sales Page 15 Pennsylvania The Man Equine Industry Study Released On a Streak One of the fastest Pennsylvania- The new Delaware Valley University study breds in training, The Man extended has determined that the equine industry his winning streak to seven with an in Southeastern Pennsylvania has a $670 eye-popping performance in the Banjo million economic impact. Page 13 Picker Sprint Stakes. Page 7 2017 PA-Bred Stakes Schedule PAGE 21 Grand Prix’s Road To Success Failing to meet her reserve twice in the auction ring, Grand Prix stayed home and has since become a dual stakes winner for Hank Nothhaft. A Letter from Executive Secretary Brian Sanfratello Page 9 Page 11 PA-Breds Eye Breeders’ Cup Championship By Emily Shields Three Pennsylvania-breds are taking their credentials into the was sold for $400,000 to Don Alberto, who turned her over to 34th Breeders’ Cup, to be run at the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club conditioner Jerry Hollendorfer. Nov. 3 and 4. -

NL-Spring-2020-For-Web.Pdf

RANCHO SAN ANTONIO Boys Home, Inc. 21000 Plummer Street, Chatsworth, CA 91311 (818) 882-6400 Volume 38 No. 1 www.ranchosanantonio.org Spring 2020 God puts rainbows in the clouds so that each of us - in the dreariest and most dreaded moments - can see a possibility of hope. -Maya Angelou A REFLECTION FROM BROTHER JOHN CONNECTING WITH OUR COMMUNITY I would like to share with you a letter from a parent: outh develop a sense of identity and value “Dear All of You at Rancho, Ythrough culture and connections. To increase cultural awareness and With the simplicity of a child, and heart full of sensitivity within our gratitude and appreciation of a parent…I thank Rancho community, each one of you, for your concern and giving of Black History Month yourselves in trying to make one more life a little was celebrated in Febru- happier… ary with a fun and edu- I know they weren’t all happy days nor easy days… cational scavenger hunt some were heartbreaking days… “give up” days… that incorporated impor- so to each of you, thank you. For you to know even tant historical facts. For entertainment, one of our one life has breathed easier because you lived, this very talented staff, a professional saxophone player, is to have succeeded. and his bandmates played Jazz music for our youth Your lives may never touch my son’s again, but I during our celebratory dinner. have faith your labor has not been in vain. And to each one of you young men, I shall pray, with ACTIVITIES DEPARTMENT UPDATE each new life that comes your way… may wisdom guide your tongue as you soothe the hearts of to- ancho’s Activities Department developed a morrow’s men. -

Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Patricia R

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College English Faculty Publications English Department 6-9-2010 Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Patricia R. Schroeder Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/english_fac Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Patricia R., "Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race" (2010). English Faculty Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/english_fac/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Until recently, scholars exploring blackface minstrelsy or the accompanying “coon song craze” of the 1890s have felt the need to apologize, either for the demeaning stereotypes of African Americans embedded in the art forms or for their own interest in studying the phenomena. Robert Toll, one of the first critics to examine minstrelsy seriously, was so appalled by its inherent racism that he focused his 1974 work primarily on debunking the stereotypes; Sam Dennison, another pioneer, did likewise with coon songs. Richard Martin and David Wondrich claim of minstrelsy that “the roots of every strain of American music—ragtime, jazz, the blues, country music, soul, rock and roll, even hip-hop—reach down through its reeking soil” (5). -

Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy

e-misférica 5.2: Race and its Others (December 2008) www.hemisferica.org “You Make Me Feel So Young”: Sinatra & Basie & Amos & Andy by Eric Lott | University of Virginia In 1965, Frank Sinatra turned 50. In a Las Vegas engagement early the next year at the Sands Hotel, he made much of this fact, turning the entire performance—captured in the classic recording Sinatra at the Sands (1966)—into a meditation on aging, artistry, and maturity, punctuated by such key songs as “You Make Me Feel So Young,” “The September of My Years,” and “It Was a Very Good Year” (Sinatra 1966). Not only have few commentators noticed this, they also haven’t noticed that Sinatra’s way of negotiating the reality of age depended on a series of masks—blackface mostly, but also street Italianness and other guises. Though the Count Basie band backed him on these dates, Sinatra deployed Amos ‘n’ Andy shtick (lots of it) to vivify his persona; mocking Sammy Davis Jr. even as he adopted the speech patterns and vocal mannerisms of blacking up, he maneuvered around the threat of decrepitude and remasculinized himself in recognizably Rat-Pack ways. Sinatra’s Italian accents depended on an imagined blackness both mocked and ghosted in the exemplary performances of Sinatra at the Sands. Sinatra sings superbly all across the record, rooting his performance in an aura of affection and intimacy from his very first words (“How did all these people get in my room?”). “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Jilly’s West,” he says, playing with a persona (habitué of the famous 52nd Street New York bar Jilly’s Saloon) that by 1965 had nearly run its course. -

November Ebn Mon

WEDNESDAY, 7TH OCTOBER 2020 ALL EYES ON KEENELAND NOVEMBER EBN MON. 9 - WED. 18 EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU TODAY’S HEADLINES TATTERSALLS EBN Sales Talk Click here to is brought to contact IRT, or you by IRT visit www.irt.com PANTILE’S BEAUTY SNAPPED UP BY BAHRAIN Bahrain’s intent as a growing power within European racing was clearly signalled when Book 1 of the Tattersalls October Yearling Sunday’s Gr.1 Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe is won by Sottsass Sale opened in Newmarket yesterday, writes Carl Evans. (Siyouni), who has been retired to join the stallion roster Operating for a member of the Gulf state’s royal family, at Coolmore. See story on page 17. bloodstock agent Oliver St Lawrence was underbidder on a 2,000,000gns half-sister to Golden Horn and then secured the session’s top lot, a son of Kingman (Lot 174), whose sale for 2,700,000gns was a windfall of epic size for breeder Colin Murfitt. IN TODAY’S ISSUE... It was also the best ring result for consignor Robin Sharp of Houghton Bloodstock, whose previous auction high was one of Steve Cargill’s Racing Week p20 500,000gns. Racing Round-up p21 The jewel which generated such a sum is a half-brother to the Gr.1 2,000 Guineas winner and sire Galileo Gold, who was First Crop Sire Maidens p26 produced by the Galileo mare Galicuix. She was bought by Pinhooking Tables p28 Murfitt for 8,000gns at the 2013 December Sale, having earlier See pages 3 & 5 – October Yearlings -

THE AGA KHAN STUDS Success Breeds Success

THE AGA KHAN STUDS Success Breeds Success 2017 CONTENTS Breeders’ Letter 5 Born To Sea 6 Dariyan 14 Harzand 20 Sea The Stars 26 Sinndar 34 Siyouni 42 Success of the Aga Khan bloodlines 52 Contacts 58 Group I Winners 60 Filly foals out of Askeria, Tarana, Tarziyna, Kerania, Alanza and Balansiya Pat Downes Manager, Irish Studs Georges Rimaud Manager, French Studs Dear Breeders, We are delighted to present you with our new roster of stallions for 2017 and would like to Prix Vermeille and Prix de Diane. Dariyan provides a fascinating opportunity for breeders take this opportunity to thank all breeders for your interest and support. as he takes up stud duties at the Haras de Bonneval in Normandy, where he joins Classic sire Siyouni, who enjoys growing success. The young sire, who started his career in 2011, 2016 was a thrilling year for the Aga Khan Studs on the racecourse, thanks to the exploits now counts ten Stakes winners and his daughters Ervedya, Volta and Spectre have been of dual Derby hero Harzand, and 2017 promises to offer an exciting breeding season as the consistent fl agbearers in Group Is throughout the year. The Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe winner son of Sea The Stars joins his illustrious sire at Gilltown Stud. Sinndar will be standing at Haras du Lion as in 2016. Harzand undoubtedly provided the highlight of the season for the green and red silks, Recognised for the quality of their stallions, the Aga Khan Studs are also renowned for becoming the 18th horse in history to record the Epsom and Irish Derby double, and a fi fth their high-class maternal lines, which was illustrated once again in 2016 due to the for H.H. -

Blackface: a Reclamation of Beauty, Power, and Narrative April 20 – June 15, 2019 Exhibition Essay - Black Face: It Ain’T About the Cork by Halima Taha

Blackface: A Reclamation of Beauty, Power, and Narrative April 20 – June 15, 2019 Exhibition Essay - Black Face: It Ain’t About the Cork by Halima Taha Blackface: It Ain’t About the Cork c 2019 Halima Taha Galeriemyrtis.net/blackface Black Face: It Ain’t About the Cork Currently ‘blackface’ has been used to describe a white adult performing a nauseatingly racist caricature of a black person; to a pair of pre-teen girls who never heard the word ‘minstrelsy’ when experimenting with costume makeup at a sleep over-- yet ‘blackfaced’ faces continue to be unsettling. Since the 19th century a montage of caricaturized images of black and brown faces, from movies, books, cartoons and posters have been ever present in the memories of all American children. Images of the coon, mammy, buck, sambo, pick-a-ninny and blackface characters, portrayed in subservient roles and mocking caricatures include images from Aunt Jemima at breakfast, to the1930’s Little Rascals, Shirley Temple in The Littlest Rebel, Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd in blackface on Saturday morning TV; to Uncle Ben staring from the cupboard-- all reinforced the demeaning representations of African Americans created to promote American white supremacy. The promotion of this ideal perpetuates the systemic suppression and suffocation of the black being. For many African Americans these images of themselves evoke an arc of emotions including: anger, sadness confusion, hurt--invisibility and shame. In 1830 Thomas Dartmouth Rice known as the “Father of Minstrelsy” developed a character named Jim Crow after watching enslaved Africans and their descendants reenacting African storytelling traditions that included folktales about tricksters, usually in the form of animals. -

INDEX to CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

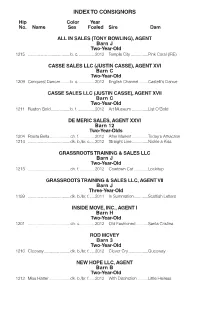

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn J Two-Year-Old 1215 ................................. ......b. c. ...............2012 Temple City ................Pink Coral (IRE) CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVI Barn C Two-Year-Old 1209 Conquest Dancer .........b. c. ...............2012 English Channel ........Castelli's Dance CASSE SALES LLC (JUSTIN CASSE), AGENT XVII Barn C Two-Year-Old 1211 Ruston Gold ..................b. f. ................2012 Art Museum ...............List O'Gold DE MERIC SALES, AGENT XXVI Barn 12 Two-Year-Olds 1204 Rosita Bella ...................ch. f. ..............2012 After Market ...............Today's Attraction 1214 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ....2012 Straight Line ...............Nickle a Kiss GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC Barn J Two-Year-Old 1213 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2012 Cowtown Cat .............Lockitup GRASSROOTS TRAINING & SALES LLC, AGENT VII Barn J Three-Year-Old 1199 ................................. ......dk. b./br. f. .....2011 In Summation .............Scottish Letters INSIDE MOVE, INC., AGENT I Barn H Two-Year-Old 1201 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 Old Fashioned ...........Santa Cristina ROD MCVEY Barn 3 Two-Year-Old 1216 Cleeway ........................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 Clever Cry ..................Queeway NEW HOPE LLC, AGENT Barn B Two-Year-Old 1212 Miss Hatter ....................dk. b./br. f. .....2012 With Distinction -

IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay Mare (Branded Nr Sh

Barn J Stables 29-36, 45-52, 61-64 On Account of EDINGLASSIE STUD, Muswellbrook (As Agent) Lot 600 IMPINGE (NZ) 49 Bay mare (Branded nr sh. off sh.) Foaled 2001 1 Nijinsky ...........................by Northern Dancer ... Caerleon ......................... SIRE Foreseer .................... by Round Table ........... GENEROUS (IRE) ..... Master Derby ............. by Dust Commander .... Doff the Derby ............... Margarethen .............. by Tulyar .................... Storm Bird .................. by Northern Dancer ... DAM Bluebird (USA) ................ Ivory Dawn ................ by Sir Ivor ................... IMCO RESOURCE (IRE) Saratoga Six ............... by Alydar .................... 1996 Sasimoto ....................... Mobcap ...................... by Tom Rolfe .............. GENEROUS (IRE) (1988). 5 wins, Ascot King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Diamond S., Gr.1. Sire of 995 rnrs, 652 wnrs, 45 SW, inc. SW Catella, etc. Sire of the dams of SW Gingernuts, Lion Tamer, Golan, Survived, Nahrain, Mourinho, We Can Say it Now, Proportional, Al Shemali, Mackintosh, Dandino, No Evidence Needed, Armure, Tartan Bearer, Essential Edge, Tungsten Strike, High Accolade, Black Moon, Vote Often, etc. 1st Dam IMCO RESOURCE (IRE), by Bluebird (USA). 2 wins at 2 at 1600m, Rome Premio Disco Rosso. Dam of 8 named foals, all raced, 5 winners, inc:- THAT'S NOT IT (g by Foreplay). 2 wins at 1100m, 1200m, $209,540, MVRC Red Anchor S., Gr 3, 2d VRC Moomba P., L. Impinge (f by Generous (Ire)). 3 wins. See below. 2nd Dam SASIMOTO, by Saratoga Six. 5 wins–3 at 2–1000m to 1400m, Milan Criterium Nazionale, L, Rome Premio Aniene, L, 3d Rome Criterium Femminile, L. Half- sister to NOTEBOOK. Dam of 11 foals, 8 to race, 7 winners, inc:- Blue Shift. 8 wins 1000m to 1408m, Rome Premio Nipissing. -

1920 Patricia Ann Mather AB, University

THE THEATRICAL HISTORY OF WICHITA, KANSAS ' I 1872 - 1920 by Patricia Ann Mather A.B., University __of Wichita, 1945 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charf;& Redacted Signature Sept ember, 19 50 'For tne department PREFACE In the following thesis the author has attempted to give a general,. and when deemed.essential, a specific picture of the theatre in early day Wichita. By "theatre" is meant a.11 that passed for stage entertainment in the halls and shm1 houses in the city• s infancy, principally during the 70' s and 80 1 s when the city was still very young,: up to the hey-day of the legitimate theatre which reached. its peak in the 90' s and the first ~ decade of the new century. The author has not only tried to give an over- all picture of the theatre in early day Wichita, but has attempted to show that the plays presented in the theatres of Wichita were representative of the plays and stage performances throughout the country. The years included in the research were from 1872 to 1920. There were several factors which governed the choice of these dates. First, in 1872 the city was incorporated, and in that year the first edition of the Wichita Eagle was printed. Second, after 1920 a great change began taking place in the-theatre. There were various reasons for this change.