Noam Chomsky - by David Barsamian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

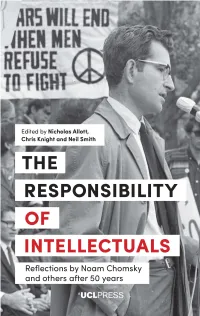

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

The Responsibility of Intellectuals EthicsTheCanada Responsibility and in the FrameAesthetics ofofCopyright, TranslationIntellectuals Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895– 1924 ExploringReflections the by Work Noam of ChomskyAtxaga, Kundera and others and Semprún after 50 years HarrietPhilip J. Hatfield Hulme Edited by Nicholas Allott, Chris Knight and Neil Smith 00-UCL_ETHICS&AESTHETICS_i-278.indd9781787353008_Canada-in-the-Frame_pi-208.indd 3 3 11-Jun-1819/10/2018 4:56:18 09:50PM First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-press Text © Contributors, 2019 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Allott, N., Knight, C. and Smith, N. (eds). The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and others after 50 years. London: UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14324/ 111.9781787355514 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. -

Chomsky and Genocide

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 8 5-7-2020 Chomsky and Genocide Adam Jones University of British Columbia Okanagan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Jones, Adam (2020) "Chomsky and Genocide," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 14: Iss. 1: 76-104. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.14.1.1738 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol14/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chomsky and Genocide Adam Jones University of British Columbia Okanagan Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada Introduction Avram Noam Chomsky (1928–) may be the most prominent and significant public intellectual of the post-World War Two period. His contributions to linguistic theory continue to generate debate and controversy. But two generations know him primarily for his political writings, public talks, and other activism, voicing a left-radical, humanist critique of US foreign policy and other subjects. Works such as American Power and the New Mandarins (1969, on Vietnam and US imperialism more generally), The Fateful Triangle: Israel, the US, and the Palestinians (1983), James Peck’s edited The Chomsky Reader (1987), and 1988’s Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (co-authored with Edward S. Herman) hold a venerated status for leftist/progressive readers. -

Class Warfare Noam Chomsky 5

NOAM CHOMSKY CLASS WARFARE interviews with DAVID BARSAMIAN ESSENTIAL CLASSICS IN POLITICS: NOAM CHOMSKY EB 0007 ISBN 0 7453 1345 0 London 1999 The Electric Book Company Ltd Pluto Press Ltd 20 Cambridge Drive 345 Archway Rd London SE12 8AJ, UK London N6 5AA, UK www.elecbook.com www.plutobooks.com © Noam Chomsky 1999 Limited printing and text selection allowed for individual use only. All other reproduction, whether by printing or electronically or by any other means, is expressly forbidden without the prior permission of the publishers. This file may only be used as part of the CD on which it was first issued. Class Warfare Noam Chomsky Interviews with David Barsamian Pluto Press London 4 First published in the United Kingdom 1996 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA This edition is not for sale in North America Copyright 1996 © Noam Chomsky and David Barsamian All rights reserved Transcripts by Sandy Adler British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7453 1138 5 hbk Digital processing by The Electric Book Company 20 Cambridge Drive, London SE12 8AJ, UK www.elecbook.com Classics in Politics: Class Warfare Noam Chomsky 5 Contents Click on number to go to page Introduction ................................................................................. 6 Looking Ahead: Tenth Anniversary Interview..................................... 8 Rollback: The Return of Predatory Capitalism ................................. 23 History and Memory.................................................................... 81 The Federal Reserve Board .........................................................130 Take from the Needy and Give to the Greedy .................................152 Israel: Rewarding the Cop on the Beat..........................................206 Classics in Politics: Class Warfare Noam Chomsky 6 Introduction In this third book in a series of interview collections, Noam Chomsky begins with comments about the right-wing agenda that have turned out to be prescient. -

Manufacturing Consent in Democratic South Africa: Application of the Propaganda Model

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE Manufacturing Consent in democratic South Africa: Application of the propaganda model Scott Lovaas Dr. Nathalie Hyde-Clarke, Advisor Witwatersrand University Johannesburg, South Africa September 2008 Revised December 2008 Lovaas 2 Contents List of acronyms and abbreviations 5 Abstract 7 Introduction 8 Chapter 1: Media ownership 47 The global media and the effects of media consolidation South African media Independent News and Media (Cape Times) Johnnic Holdings (Business Day) Naspers (Natal Witness) Interlocking capital Impacts of corporate media Media, markets, and democracy Watering down democracy Decreased competition and diversity of opinion Media beholden to advertisers Rise of sensationalism Protecting self-interest Conclusion Chapter 2: Advertising 87 Advertising underwrites and marginalises Advertising promotes an economic way of life Suppression, self-censorship, and direct pressure Conclusion Chapter 3: Forestry 103 A brief history of forestry in South Africa South African forestry today Terms Methodology Sources Sourcing methodology and scoring Analysis of sources by category Workers, unions, and progressive society Lovaas 3 Environmental groups Community members or representatives Analysis of sources by newspaper Business Day Cape Times Natal Witness Range of expressible opinion Breakdown of articles by genre Environmental impact Labour Community forestry and woodlots Privatisation and Komatiland -

Featured Selections the New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo

http://www.zmag.org/chomsky/books.cfm Books Jump to: Featured Selections | Major Works | Interview-Based Books | Books In Print Only Featured Selections Top The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel and the Palestinians (excerpts) Updated for 1999! "This is a jeremiad in the prophetic tradition, an awesome work of latter-day forensic scholarship by a radical critic of America and Israel." —Boston Globe "[This is] a monumental work.... Chomsky's command of factual detail is overwhelming, his argument is cogently made, and the documentation, which makes much use of the Israeli and European press, is careful. Recommended to students of US foreign policy, the modern Middle East, and to all general readers." —Choice Published by South End Press (1999, 600 pages). $18 paperback / $40 cloth. Rogue States: The Rule of Force in World Affairs In his newest book, Chomsky holds the world’s superpowers to their own standards of the rule of law—-and finds them appallingly lacking. Rogue States is the latest result of his tireless efforts to measure the world’s superpowers by their own professed standards and to hold them responsible for the indefensible actions they commit in the name of democracy and human rights. Published by South End Press (2000, 264 pages). The New Military Humanism: Lessons From Kosovo Was the war over Kosovo really a multi-national effort waged solely for humanitarian reasons? Or was it the establishment of a new world order headed by self-proclaimed "enlightened states" with enough military might to ignore international law and world opinion? In this book, begun after the NATO bombs started dropping in Yugoslavia and finished as the defeated Serbian forces were leaving the Kosovo province, Chomsky gives us an overview of a changing world order with "might makes right" as its foundation. -

Noam Chomsky and the Public Intellectual in Dark Times

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 11 • Issue 1 • 2014 doi:10.32855/fcapital.201401.001 Noam Chomsky and the Public Intellectual in Dark Times Henry A. Giroux In a market-driven system in which economic and political decisions are removed from social costs, the flight of critical thought and social responsibility is accentuated by what Zygmunt Bauman calls “ethical tranquillization.”[1] One result is a form of depoliticization that works its way through the social order, removing social relations from the configurations of power that shape them, substituting what Wendy Brown calls “emotional and personal vocabularies for political ones in formulating solutions to political problems.”[2] Consequently, it becomes difficult for young people too often bereft of a critical education to translate private troubles into public concerns. As private interests trump the public good, public spaces are corroded and short-term personal advantage replaces any larger notion of civic engagement and social responsibility. Under the restricted rationality of the market, pubic spheres and educational realms necessary for students to imagine alternative futures and horizons of possibility begin to disappear as do the public intellectuals who embrace “the idea of a life dedicated to values that cannot possibly be realized by a commercial civilization [who rejects the idea that] loyalty, not truth, provides the social condition by which the intellectual discovers his new environment.”[3] In a dystopian world shaped by twenty-five years of neoliberal savagery with its incessant assault on public values, the common good, and social responsibility, it has become difficult to remember what a purposeful and substantive democracy looks like or for that matter what the idea of democracy might suggest. -

Manufacturing Consent

HOME • Chronology of Terror • Bibliographies • Valuable Websites • About This Site • SITE MAP ACTION • NEWS • Solutions • Candles in the darkness • Revealing Quotes 1 2 3 • Letters • SEARCH Manufacturing Consent Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky Pantheon Books, 1988; ISBN 0-679-72034-0 Contrary to the commonly believed image of the press as cantankerous, obstinate and thorough in its search for truth, Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky show that, in fact, a highly prejudiced elite consensus creates the state propaganda that is presented daily as “news.” They skillfully dissect the way in which the marketplace and the economics of publishing significantly shape the news. They reveal how issues are framed and topics are chosen. As a prime example, they reveal the fact that totally dishonest double standards are used by the corporate media when “reporting” about countries which are puppets of the U.S., and countries which attempt to be free of the U.S. In the corporate mass-media’s propagandistic accounts of so-called “free elections,” a “free press,” and governmental repression, Herman and Chomsky contrast the double standards which were used between Nicaragua and El Salvador; between the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and the American invasion of Vietnam; between the genocide in Cambodia under a pro-American government and genocide under Pol Pot (which was later supported by the U.S. government). They explore how Watergate and the Iran-Contra hearings manifested not an excess but a lack of investigative zeal into the accumulating illegalities of the executive branch. -

Noam Chomsky and the Institutional Analysis of Power

Understanding Propaganda: Noam Chomsky and the Institutional Analysis of Power Partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political and International Studies Paul Eben Cathey May 2009 Abstract ___________________________________________________________________________ This thesis argues that Noam Chomsky’s theory of propaganda is a useful way to understand class domination. The strengths and weaknesses of Chomsky’s theory are examined by means of a comparison with Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony. Since work that discusses and analyses Chomsky’s theory is sparse, this piece first gives a detailed explanation of his theory. This requires a short clarification of Chomsky’s terminology, focusing on his definitions of indoctrination and class. Thereafter a thorough account of Chomsky’s ideas regarding class structure, the indoctrinating functions of educational and media institutions and the difference between upper and lower class propaganda are discussed. A common criticism of Chomsky’s arguments is that they are conspiratorial. Thus, following the discussion of Chomsky’s theory I present an argument that Chomsky uses an institutional analysis as opposed to conspiracy theory to reach his conclusions. After arguing that Chomsky has a coherent, logical theory of propaganda that is not conspiratorial, this thesis shifts to a comparison of Chomsky and Gramsci’s theory. The elements of Gramsci’s theory that are relevant to Chomsky are discussed, focusing on their overall similarities, in particular, the question of consent. The final chapter consists of a comparison of the two theories, examining each theorist’s ideas on the nature of education, language, consent and the possible ways in which the lower classes can oppose their own oppression. -

The Social and Political Thought of Noam Chomsky

The Social and Political Thought of Noam Chomsky The quality of Edgley’s work is very high. The exposition of Chomsky’s work is always clear and judicious. Edgley provides a sound treatment of the material and pays excellent attention to the broader context of the argument…. In the existing literature there is nothing quite like this in its treatment of Chomsky. Professor David McLellan, University of Kent This book explores the theoretical framework that enables Chomsky to be consistently radical in his analysis of contemporary political affairs. It argues that, far from Chomsky being a ‘conspiracy theorist’, his approach is embedded within a systematic philosophical understanding of human nature, combined with critical perspectives on the state, nationalism and the media. When compared to Marxist, liberal and cultural relativist thought, Chomsky’s libertarian socialist thought provides coherent grounds for a militant optimism. The Social and Political Thought of Noam Chomsky questions Chomsky’s claim not to have a theory about the relationship between human beings and their society other than that which can be ‘written on the back of a postage stamp’. Edgley compares Chomsky’s vision of the good society with liberal and communitarian perspectives, and establishes that it is grounded in a hopeful belief about human nature. She argues that sympathy with this vision of the good society is essential for understanding the nature of Chomsky’s critique of state capitalism, its inherent nationalism and the media. The author concludes that Chomsky’s analysis is coherent and systematic when one acknowledges that he is not just a critic but a theorist. -

A Critical Review and Assessment of Herman and Chomsky's

A Critical Review and Assessment of Herman and Chomsky’s ‘Propaganda Model’ j Jeffery Klaehn ABSTRACT j Mass media play an especially important role in democratic societies. They are presupposed to act as intermediary vehicles that reflect public opinion, respond to public concerns and make the electorate cognizant of state policies, important events and viewpoints. The fundamental principles of democracy depend upon the notion of a reasonably informed electorate. The ‘propaganda model’ of media operations laid out and applied by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media postulates that elite media interlock with other institutional sectors in ownership, management and social circles, effectively circumscribing their ability to remain analytically detached from other dominant institutional sectors. The model argues that the net result of this is self-censorship without any significant coercion. Media, according to this framework, do not have to be controlled nor does their behaviour have to be patterned, as it is assumed that they are integral actors in class warfare, fully integrated into the institutional framework of society, and act in unison with other ideological sectors, i.e. the academy, to establish, enforce, reinforce and ‘police’ corporate hegemony. It is not a surprise, then, given the interrelations of the state and corporate capitalism and the ‘ideological network’, that the propaganda model has been dismissed as a ‘conspiracy theory’ and condemned for its ‘overly deterministic’ view of media behaviour. It is generally excluded from scholarly debates on patterns of media behaviour. This article provides a critical assessment and review of Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda Jeffery Klaehn is part-time instructor, Department of Sociology and Anthro- pology, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.